James Hope (Ireland)

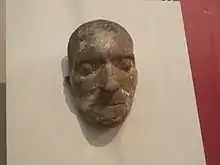

James "Jemmy" Hope (August 25, 1764 – February 10, 1847) was a radical democrat in Ireland who organised among tenant farmers, tradesmen and labourers for the Society of the United Irishmen. In the Rebellion of 1798 he fought alongside Henry Joy McCracken at the Battle of Antrim. In 1803 he attempted to renew the insurrection against the British Crown in an uprising co-ordinated by Robert Emmett and Anne Devlin. Among United Irishmen Hope was distinguished by his conviction that "the fundamental question at issue between the rulers and the people" was "the condition of the labouring class".[1]

James "Jemmy" Hope | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1764 |

| Died | 1847 |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Weaver, Revolutionary |

| Movement | Irish Volunteers, |

Background

Hope was born in Mallusk (parish of Templepatrick), County Antrim. His father, John Hope, a Scottish highlander and linen weaver, had emigrated from Scotland rather than compromise his Presbyterian Covenanter faith.[2]

At age ten Hope was hired on a nearby farm. On winter evenings his master would make him sit "while he read in the Histories of Greece and Rome, and also Ireland, Scotland and England." Hope recalls that, together with comments on the news of the day, this turned his attention "early to the nature of the relations between the different classes of society".[3] Labouring on the land, at a time when in Antrim the tenant Hearts of Steel led a violent resistance into the exactions of the largely Anglican landlords, Hope came to believe that "The Most High is lord of the soil; the cultivator is his tenant", and that landlords who abused this relationship were oppressors.[4]

Hope was later apprenticed as a linen weaver, then as a journeyman, while continuing his education at night classes. He married the daughter of an employer, Rose Mullen.

Irish Volunteer

In the wake of the American Revolution, Hope joined the Roughfort Corps of the Irish Volunteers. By his own account, his "connection with politics began in the ranks of the Volunteers": they were "the means of breaking the first link in the penal chain". He identified the source of the country's poverty and distress.

As a people, we were excluded from any share in framing the laws by which we were governed ... By force the poor were subdued and dispossessed of their interests in the soil; by fiction, the titles of the spoilers were established; and by fraud on the productive industry of future generations, the usurpation was continued.[5]

Parading with his Volunteer company on Bastille Day in Belfast in 1792, Hope James carried a green flag with the inscription; “Our Gallic brother was born on the 14th July 1789 alas we are still in embryo Superstitious galaxy the Irish Bastille let us unite to destroy it.”

It was in the Volunteers that Hope first met Henry Joy McCracken and Samuel Neilson. After the movement split on the question of Catholic emancipation and was suppressed by the government in 1793, he joined them in the Society of the United Irishmen, [6] albeit with some reservation. Hope "lamented that we should shrink from an open declaration of our views into conspiracy". Oaths, he cautioned, "will never bind rogues".[7]

United Irishman

Hope sensed that in some quarters the movement for reform had been "merely between commercial and aristocratical interests, to determine which should have the people as its prey".[8] But when in 1795 Hope took the United Irish pledge (or "test") to "persevere in endeavouring to form a brotherhood of affection among Irishmen of every religious persuasion", and "to obtain an equal, full and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland", the Society was abandoning its hopes for parliamentary reform. Increasingly, thoughts turned toward insurrection and to prospects for assistance from the new French Republic.

Hope quickly established himself as a prominent organiser and was elected to the northern committee in Belfast. Together with Thomas Addis Emmet in Dublin, he accounted Neilson and McCracken and Thomas Russell in the north the only United Irish leaders who "perfectly" understood the real causes of social disorder and conflict: "the conditions of the labouring class".[9] For Hope, Belfast was the centre in Ulster of a “factitious system” in which ultimately there was but:

...three parties: those whose industry produced the necessaries of life, those who circulated them, and those whose subsistence depended on fictitious claims and capital, and lived and acted as if men and cattle were created solely for their use and benefit...[10]

In this Hope was perhaps closest to Russell. Commenting on growing trades union activity in Belfast and the surrounding districts[11] in the pages of the movement's paper, the Northern Star, Russell urged "combinations" (labour unions) not only for tradesmen but also for labourers and cottiers.[12]

In the spring of 1796, Neilson sent Hope to Dublin to help organise the workers in the capital. Himself working as a cotton weaver, Hope first recruited textile workers in Balbriggan. Then, targeting illegal workers’ combinations, he helped the spread of the organisation, with a considerable Protestant artisan membership, south of the river into the The Liberties. (When the rising came in May 1798, and it was clear that the city's garrison would prevent a United Irish demonstration in the capital, many of these workers quit the city to join the rebel standard in the countryside).[6]

Hope also travelled to counties in Ulster and Connaught and into the Wicklow Mountains, disseminating literature and organizing localities. In one week alone, he travelled over 700 miles.[13] In the midst of the Armagh Disturbances. working in parallel with Father James Coigly,[14] he sought to reconcile the Peep o'Day Boys to their traditional enemies, the Catholic Defenders in the cause of what was simply called "The Union".[4]

1798 rebellion

Hope noted that union membership of "rich farmers and shopkeepers" ebbed under the pressure of martial law but flowed again on a wider popular tide after attempted French landing at Bantry in December 1796 made real the prospect of French assistance. From December to May 1797 membership in Ulster alone increased fourfold, reaching 117,917.[15] When the call to arms finally came in the north in June 1798, however, he recognised that many of the wealthier union men had "staked more than was really in them".[16]

Hope "remained steadfast" and led a "Spartan band" of weavers and labourers who covered the retreat of the rebels under the command of Henry Joy McCracken at the Battle of Antrim. Hope managed to re-join McCracken and his remaining forces after the battle at their camp upon Slemish mountain, but the camp gradually dispersed, and the dwindling band of insurgents were then forced to go on the run. He successfully eluded capture, but his friend McCracken was captured and executed on 17 July. Upon the collapse of the general rising, Hope refused to avail of the terms of an amnesty offered by Lord Cornwallis on the grounds that to do so would be "not only a recantation of one’s principles but a tacit acquiescence in the justice of the punishment which had been inflicted on thousands of my unfortunate associates".[17]

1803 rising

Hope lived a precarious existence with his wife and family in Dublin running a small haberdasher's shop in Dublin but having to flee the city on a number of occasions. With Thomas Russell, in 1803 he became involved in Robert Emmet and Anne Devlin's plans to revive the republican insurrection. He made contact with Michael Dwyer (Devlin’s cousin), who still maintained rebel resistance in the Wicklow Mountains, and then headed north seeking to raise Antrim while Russell mustered supporters in Down. But those districts of Antrim where he had previously found "the republican spirit, inherent in the principles of Presbyterian community, kept resistance to arbitrary power still alive"[18] refused the call.

Russell was similarly rebuffed when attempting to raise the standard in the Defender country of south Down.[19] Meanwhile in Dublin, after a brief street battle on the evening of the 23rd, in which he had recoiled from the sight of a dragoon being pulled from his horse and piked to death, Emmett called the rising off.[20]

Last years

Hope evaded the authorities attention in the ensuing repression by securing employment with a sympathetic friend from England in Belfast where he benefitted from a political amnesty in 1806. He continued to work as a weaver, wrote poetry and his memoirs. In the 1840s, well into his seventies and despite his doubts about the nature of O'Connellism, Hope chaired a meeting of the Repeal Association seeking to reverse the 1800 Acts of Union and restore an independent Irish parliament.[4]

Hope died in Brown Square, Belfast, in 1847 aged 83 and was buried, in the Mallusk cemetery, Newtownabbey. The headstone was raised by his friends, Henry Joy McCracken’s sister Mary Ann, and the Shankill Road United Irishman Isreal Milliken. The historian Richard Robert Madden, who had encouraged Hope to write his memoirs, supplied the inscription:[21]

Sacred to the memory of James Hope ... One of nature's noblest works, an honest man. ... In the best era of his country's history a soldier in her cause, and in the worst of times, still faithful to it: ever true to himself and those that trusted in him. He remained to the last unchanged and unchangeable in his fidelity.

Underneath is the outline of a large dog, which supposedly brought provisions to Hope and his comrades when they were hiding following the Battle of Antrim.

Hope and his wife Rose Mullen's first child, Luke Hope, became the editor of the Northern Star, the United Irish newspaper. They had at least three further children all named in honour of Hope's associates in the movement: two sons named Henry Joy McCracken Hope, the first having died in infancy; Robert Emmett Hope; and, named after Wolfe Tone's wife, Mathilda Hope.[22]

Film

James Hope is portrayed by Des McAleer in Pat Murphy's 1984 film Anne Devlin.

References

- Madden, Robert (1900). Antrim and Down in '98 : The Lives of Henry Joy m'Cracken, James Hope, William Putnam m'Cabe, Rev. James Porter, Henry Munro. Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Co. p. 108.

- Bob Armstrong (1998), "Jemmy Hope--Writer and Revolutionary", in The Liberty Tree: The story of the United Irishmen in and around the Borough of Newtownabbey, Archie R. Reid (ed.), A Newtownabbey Borough Council Bi-Centenary Publication. ISBN 0953337308.pp. 33-48

- Madden, Richard Robert (1846). The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times. Volume 1. Belfast: J. Madden & Company. p. 92. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 109–111. ISBN 9781909556065.

- Madden (1846) p. 235

- Whelan, Fergus. "Jemmy Hope: the most Radical United Irishman". Look Left. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- quoted in Armstrong (1998), p. 37

- Madden, Robert (1900). Antrim and Down in '98 : The Lives of Henry Joy m'Cracken, James Hope, William Putnam m'Cabe, Rev. James Porter, Henry Munro. Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Co. p. 104.

- Madden (1900), p. 108

- Jemmy Hope (1972), The Memoirs of Jemmy Hope, B&ICO Publication, Belfast, p. 17.

- Gray, John (1998). The San Culottes of Belfast: The United Irishmen and the Men of No Property. Belfast: Belfast Trades Union Council and the United Irishmen Commemorative Society. pp. 13–18.

- Quinn, James (2002). "Thomas Russell, United Irishman". historyireland.com. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Armstrong (1998), p. 37

- Keogh, Daire (Summer 1998). "An Unfortunate Man". 18th - 19th Century History. 5 (2). Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Bew, John (2011). Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny. London: Quercus. p. 107. ISBN 9780857381866.

- Hope, James (2001). United Irishman: The Autobiography of James Hope (John Newsinger ed.). London: Merlin Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780850364965.

- Hope (2001) p.79

- Bardon, Jonathan (1982). Belfast: An Illustrated History. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 60. ISBN 0856402729.

- Commentary by Kenneth Robinson in: Birch, Thomas Ledlie (2005). A Letter from an Irish Emigrant (1799) (Originally published in Philadelphia ed.). Belfast: Athol Books. ISBN 0850341108. p. 114

- "Robert Emmet". Ricorso. 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- McNeill, Mary (1960). The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken. Dublin: Alan Figgis & Co. p. 302.

- Armstrong (1998) p. 36