Japanese cruiser Kasuga

Kasuga (春日, Vernal Sun) was the name ship of the Kasuga-class armored cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy, built in the first decade of the 20th century by Gio. Ansaldo & C., Sestri Ponente, Italy, where the type was known as the Giuseppe Garibaldi class. The ship was originally ordered by the Royal Italian Navy as Mitra in 1901 and sold in 1902 to Argentine Navy who renamed her Bernardino Rivadavia during the Argentine–Chilean naval arms race, but the lessening of tensions with Chile and financial pressures caused the Argentinians to sell her before delivery. At that time tensions between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire were rising, and the ship was offered to both sides before she was purchased by the Japanese.

Kasuga at Sasebo after the Battle of Tsushima, May 1905 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Kasuga |

| Namesake: | Kasuga Shrine |

| Ordered: | 23 December 1901 |

| Builder: | Gio. Ansaldo & C., Genoa-Sestri Ponente |

| Laid down: | 10 March 1902 |

| Launched: | 22 October 1902 |

| Acquired: | 30 December 1903 |

| Commissioned: | 7 January 1904 |

| Fate: |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Giuseppe Garibaldi-class armored cruiser |

| Displacement: | 7,700 t (7,578 long tons) |

| Length: | 111.73 m (366 ft 7 in) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 18.71 m (61 ft 5 in) |

| Draft: | 7.31 m (24 ft 0 in) |

| Depth: | 12.1 m (39 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Range: | 5,500 nmi (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 560 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, Kasuga participated in the Battle of the Yellow Sea and was lightly damaged during the subsequent Battle of Tsushima. In addition, she frequently bombarded the defenses of Port Arthur. The ship played a limited role in World War I and was used to escort Allied convoys and search for German commerce raiders in the Indian Ocean and Australasia. Kasuga became a training ship in the late 1920s and was then disarmed and hulked in 1942 for use as a barracks ship. The ship capsized shortly before the end of World War II in 1945 and was salvaged three years later and broken up for scrap.

Background

Kasuga was the next-to-last of the 10 Giuseppe Garibaldi-class armored cruisers to be built. The first ship had been completed in 1895 and the class had enjoyed considerable export success and had been gradually improved over the years.[1] The last two ships of the class were ordered on 23 December 1901 by the Royal Italian Navy and sold the next year to the Argentine Navy in response to the order placed with a British shipbuilder by Chile for two second-class battleships. The possibility of war between Argentina and Chile, however, abated before the vessel was completed, and a combination of financial problems and British pressure forced Argentina to dispose of Bernardino Rivadavia and her sister ship Mariano Moreno. The Argentine government attempted to sell the ships to Russia, but negotiations failed over the price demanded by the Argentinians. The Japanese government quickly stepped in and purchased them due to increasing tensions with Russia despite the high price of ¥14,937,390 (£1,530,000) for the two sisters. Already planning to attack Russia, the government delayed their surprise attack on Port Arthur that began the Russo-Japanese War until the ships had left Singapore and could not be delayed or interned by any foreign power.[2]

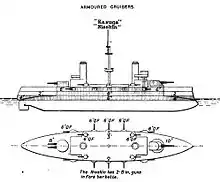

Design and description

Kasuga had an overall length of 111.73 meters (366 ft 7 in), a beam of 18.71 meters (61 ft 5 in), a molded depth of 12.1 meters (39 ft 8 in) and a deep draft (ship) of 7.31 meters (24 ft 0 in). She displaced 7,700 metric tons (7,600 long tons) at normal load. The ship was powered by two vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one shaft, using steam from 8 coal-fired Scotch marine boilers. Designed for a maximum output of 13,500 indicated horsepower (10,100 kW) and a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), Kasuga barely exceeded this, reaching a speed of 20.05 knots (37.13 km/h; 23.07 mph) during her sea trials on 20 September 1903 despite 14,944 ihp (11,144 kW) produced by her engines. She had a cruising range of 5,500 nautical miles (10,200 km; 6,300 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[3] Her complement consisted of 560 officers and enlisted men.[4]

Her main armament consisted of one 40-caliber Armstrong Whitworth 10-inch/40 Type 41 gun in a single turret forward and two 8-inch/45 Type 41 guns, in a twin-gun turret aft. Ten of the quick-firing (QF) 6-inch/40 Type 41 guns that comprised her secondary armament were arranged in casemates amidships on the main deck; the remaining four guns were mounted on the upper deck. Kasuga also had ten QF 3-inch/40 Type 41 guns and six QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns to defend herself against torpedo boats. She was fitted with four submerged 457 mm (18.0 in) torpedo tubes, two on each side.[5]

In 1924 two of her 3 in/40 guns were removed, as were all of her QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns, and a single 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type anti-aircraft gun was added.[6] By August 1933, all ten of her casemated 6-inch guns had been removed in addition to four more 3 in/40 guns.[7]

The ship's waterline armor belt had a maximum thickness of 150 millimeters (5.9 in) amidships and tapered to 70 millimeters (2.8 in) towards the ends of the ship. Between the main gun barbettes it covered the entire side of the ship up to the level of the upper deck. The ends of the central armored citadel were enclosed by transverse bulkheads 120 millimeters (4.7 in) thick. The forward barbette, the conning tower, and gun turrets were also protected by 150-millimeter armor while the aft barbette only had 100 millimeters (3.9 in) of armor. Her deck armor ranged from 20 to 40 millimeters (0.8 to 1.6 in) thick and the 6-inch guns on the upper deck were protected by gun shields.[8]

Construction and career

The ship's keel was laid down on 10 March 1902 with the temporary name of San Mitra and she was launched on 22 October 1902 and renamed Bernardino Rivadavia by the Argentinians.[5] The vessel was sold to Japan on 30 December 1903[9] and renamed Kasuga, after Kasuga Shrine in Nara prefecture,[10] on 1 January 1904. Kasuga and her newly renamed sister Nisshin were formally turned over to Japan and commissioned on 7 January.[9] The sisters departed Genoa on 9 January under the command of British captains and manned by British seamen and Italian stokers. When they arrived at Port Said, Egypt, five days later, they encountered the Russian protected cruiser Aurora and reached Suez on the 16th, accompanied by the British armored cruiser King Alfred. The Japanese ships reached Singapore on 2 February where they were slightly delayed by a coolie strike.[11]

Russo-Japanese War

Kasuga and Nisshin reached Yokosuka on 16 February just as Japan initiated hostilities with its surprise attack on Port Arthur, and began working up with Japanese crews. The sisters were assigned to reinforce the battleships of the 1st Division of the 1st Fleet under the overall command of Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō on 11 April. In an effort to block the Russian ships in Port Arthur, Togo ordered a minefield laid at the mouth of the harbor on 12 April and Kasuga and Nisshin were tasked to show themselves "as a demonstration of our power".[12] Tōgō successfully lured out a portion of the Russian Pacific Squadron, including Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov's flagship, the battleship Petropavlovsk. When Makarov spotted the five Japanese battleships and Kasuga and Nisshin, he turned back for Port Arthur and his flagship ran into the minefield just laid by the Japanese. The ship sank in less than two minutes after one of her magazines exploded, and Makarov was one of the 677 killed. In addition to this loss, the battleship Pobeda was damaged by a mine.[13] Emboldened by his success, Tōgō resumed long-range bombardment missions, making use of the long-range capabilities of Kasuga and Nisshin's guns to blindly bombard Port Arthur on 15 April from Pigeon Bay, on the southwest side of the Liaodong Peninsula, at a range of 9.5 kilometers (5.9 mi).[14] In early May, the sisters fired at ranges up to 18 kilometers (11 mi) although this proved to be ineffective.[15]

On 15 May, the battleships Yashima and Hatsuse were sunk by Russian mines. That same day, off Port Arthur, Kasuga collided in the fog with the protected cruiser Yoshino, which capsized and sank with the loss of 318 officers and enlisted men.[16] With a third of Japan's battleships lost, Tōgō decided to use Kasuga and Nisshin in the line of battle together with his four remaining battleships.[17] The first test of this decision would have occurred on 23 June when the Pacific Squadron sortied in an abortive attempt to reach Vladivostok, but the new squadron commander, Rear Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, ordered the squadron to return to Port Arthur when it encountered the Japanese battleline (including Kasuga and Nisshin) shortly before sunset, as he did not wish to engage his numerically superior opponents in a night battle.[18] On 27 July, the sisters forced a Russian force of one battleship and several cruisers and gunboats to return to port because of long-range gun fire after they sortied to provide fire support to the Russian Army.[19]

Kasuga and Nisshin participated in the Battle of the Yellow Sea on 10 August, but only played a minor role as they were in the rear of the Japanese battleline. During the battle, the ship's executive officer was Kantarō Suzuki, later Prime Minister of Japan.[20] Kasuga was not significantly damaged, although she was hit three times with 11 crewmen wounded.[21] Kasuga fired 33 ten-inch shells along with an unknown number of eight-inch shells during the battle.[22] After the battle the sisters returned to Pigeon Bay where they engaged the Russian fortifications.[23]

At the Battle of Tsushima on 26 May 1905, Kasuga was fifth in the line of battle. At about 14:10, Kasuga opened fire on the battleship Oslyabya, the lead ship in the second column of the Russian fleet. Due to the limited visibility and heavy smoke during the battle detailed knowledge is not available about her activities during the rest of the day's action.[24] The surviving Russian ships had been located near the Liancourt Rocks by the Japanese the following morning and Tōgō reached them about 10:00. Heavily outnumbering the Russians, he opted for a long-range engagement to minimize any losses and Kasuga opened fire at the obsolete battleship Imperator Nikolai I at a range of 9,100 meters (10,000 yd). The ship hit her target's funnel on her third salvo and the Russians surrendered shortly afterwards.[25]

During the course of the battle, Kasuga fired 50 ten-inch and 103 eight-inch shells; due to the poor visibility and sinking of many Russian ships, the only confirmed hits made by the ship were two against the battleship Oryol with ten-inch shells, one of which broke up on the armor of the aft twelve-inch (305 mm) turret. In return she was struck by one 12-inch, one 6-inch, and one unidentified shell, none of which significantly damaged her.[26]

Shortly after the Battle of Tsushima, Kasuga was assigned to the 3rd Fleet) for the invasion and occupation of Sakhalin in July–August.[27] On 2 September 1911, the ship escorted the ex-Russian torpedo depot ship Anegawa to Vladivostok to be returned to the Russians.[28] At the start of 1914, Kasuga was overhauled with her boilers replaced by 12 Kampon Type 1 water-tube boilers.[29]

World War I

Kasuga served as the flagship of Destroyer Squadron (Suiraisentai) 3 from 13 December 1915 to 13 May 1916 and 12 September 1916 to 13 April 1917.[30] After the incursion of the German commerce raider SMS Wolf into the Indian Ocean in March 1917, the British Admiralty requested that the Japanese government reinforce its ships already present, there and in Australian waters.[31] The ship was sent south and escorted Allied shipping between Colombo, Ceylon and Fremantle, Australia in April–May.[32] She was based at Singapore through November.[33] On 11 January 1918, Kasuga ran aground on a sandbank in the Bangka Strait, in the Dutch East Indies, where she was stuck until June, when she could finally be refloated for repairs.[7]

Interwar years and World War II

Kasuga arrived in Portland, Maine on 3 July 1920 for the centennial celebrations of the State of Maine[34] and then made port visits in New York City and Annapolis, Maryland.[35] In August 1920 Kasuga visited the city of Cristobal in the Republic of Panama, after transiting the Panama Canal, from 22 to 25 August 1920, with an official reception for the crew before heading to San Francisco.[36]

She was used to transport Japanese soldiers and supplies to Siberia in 1922 as part of Japan's Siberian Intervention.[37] During the time, Kasuga was commanded by Mitsumasa Yonai, another future Prime Minister of Japan.[38] On 15 June 1926, the ship helped to rescue the crew of the freighter SS City of Naples that struck a rock off the coast of Japan and broke up. Two of her crewmen were later awarded silver medals for gallantry during the rescue by King George V.[39]

From 1927 to 1942, Kasuga was used as a training vessel for navigators and engineers.[7] On 27 July 1928 she rescued the crew of the semi-rigid airship N3 after it exploded in heavy weather during fleet maneuvers.[40] In January–February 1934, Kasuga ferried 40 scientists to Truk to observe a total solar eclipse on 14 February.[41] She was hulked and disarmed in July 1942 and used as a floating barracks for the rest of the Pacific War. Kasuga capsized at her mooring at Yokosuka on 18 July 1945 during an air raid by United States Navy aircraft from TF-38. Her wreck was salvaged in August 1948 and broken up for scrap by the Uraga Dock Company.[7][10]

Notes

- Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 351; Milanovich, p. 92; Silverstone, p. 314

- Milanovich, pp. 83–84

- Milanovich, pp. 87, 90

- Silverstone, p. 314

- Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 226

- Chesneau, p. 174

- Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 75

- Milanovich, pp. 87, 89

- Milanovich, p. 84

- Silverstone, p. 332

- "The Arrival of the Nisshin and Kasuga". The Russo-Japanese War Fully Illustrated. Tokyo: Kinkodo Publishing Co. & Z. P. Maruya & Co. (1): 98–99. April–July 1904.

- Warner & Warner, pp. 235–36

- Forczyk, pp. 45–46

- Great Britain, War Office: General Staff (1906). The Russo-Japanese War. Part I. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 51.

- Evans & Peattie, p. 99

- Warner & Warner, pp. 280–82

- Forczyk, p. 48

- Warner & Warner, pp. 305–06

- McLaughlin, p. 62

- Kowner, p. 363

- Empire of Japan, Naval General Staff (September–October 1914). "Battle of the Yellow Sea: The Official Version of the Japanese General Staff". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. 40 (5): 1289.

- Forcyzk, pp. 48–51, 73

- Warner & Warner, p. 339

- Campbell, pp. 127–31

- Forczyk, pp. 70–71

- Campbell, pp. 258, 260, 263

- Corbett, II, p. 357

- "Ship Returned by Japan". Derby Daily Telegraph. 4 September 1911. p. 2. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, pp. 75, 244

- Lacroix & Wells, p. 552

- Newbolt, pp. 214–17

- Hirama, pp. 143–44

- Newbolt, p. 225

- "Cruiser Arrives" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 July 1920. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "Kasuga Off for Annapolis" (PDF). The New York Times. 21 July 1920. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "Visit of the Kasuga". Panama Canal Record. p. 16. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 225

- Stewart, p. 292

- "Japanese Navymen". Aberdeen Journal. p. 7. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Destruction of a Dirigible". Hartlepool Mail. 24 October 1928. p. 3. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Scientists Invade Island". Dundee Courier. 27 January 1934. p. 4. Retrieved 9 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

References

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1978). "The Battle of Tsu-Shima, Parts 1, 2 and 4". In Preston, Antony (ed.). Warship. II. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 46–49, 127–35, 258–65. ISBN 0-87021-976-6.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1994). Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-129-7.

- Evans, David & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. Botley, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Hirama, Yoichi (2004). "Japanese Naval Assistance and its Effect on Australian-Japanese Relations". In Phillips Payson O'Brien (ed.). The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 140–58. ISBN 0-415-32611-7.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. Historical Dictionaries of War, Revolution, and Civil Unrest. 29. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81084-927-3.

- Lacroix, Eric & Wells, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (September 2008). Ahlberg, Lars (ed.). "Retvizan". Contributions to the History of Imperial Japanese Warships (Paper V): 60–63.(subscription required)(contact the editor at lars.ahlberg@halmstad.mail.postnet.se for subscription information)

- Milanovich, Kathrin (2014). "Armored Cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2014. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-236-8.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. IV (reprint of the 1928 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-253-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Stewart, William (2009). Admirals of the World: A Biographical Dictionary, 1500 to the Present. McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-3809-6.

- Warner, Denis & Warner, Peggy (2002). The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905 (2nd ed.). London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japanese cruiser Kasuga. |