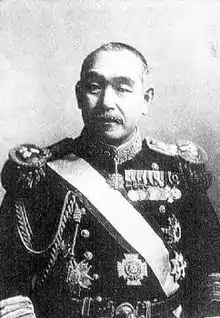

Kantarō Suzuki

Baron Kantarō Suzuki (鈴木 貫太郎, 18 January 1868 – 17 April 1948[1]) was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, member and final leader of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association and Prime Minister of Japan from 7 April to 17 August 1945.

Kantarō Suzuki | |

|---|---|

鈴木 貫太郎 | |

| |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 7 April 1945 – 17 August 1945 | |

| Monarch | Shōwa |

| Preceded by | Kuniaki Koiso |

| Succeeded by | Naruhiko Higashikuni |

| President of the Privy Council of Japan | |

| In office 10 August 1944 – 7 April 1945 | |

| Monarch | Shōwa |

| Preceded by | Yoshimichi Hara |

| Succeeded by | Hiranuma Kiichirō |

| In office 15 December 1945 – 13 June 1946 | |

| Preceded by | Hiranuma Kiichirō |

| Succeeded by | Shimizu Tōru |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 January 1868 Kuze, Izumi, Empire of Japan |

| Died | 17 April 1948 (aged 80) Noda, Chiba, Occupied Japan |

| Political party | Imperial Rule Assistance Association (1940–1945) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (Before 1940 and after 1945) |

| Spouse(s) | Suzuki Taka |

| Children | Suzuki Ichi Fujie Sakae Adachi Mitsuko |

| Alma mater | Imperial Japanese Naval Academy |

| Profession | Admiral, politician |

| Awards | Order of the Golden Kite (3rd class) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1887–1929 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Akashi, Soya, Shikishima, Tsukuba Maizuru Naval District, IJN 2nd Fleet, IJN 3rd Fleet, Kure Naval District, Combined Fleet |

| Battles/wars | |

Biography

Early life

Suzuki was born in Kuze village, Izumi Province (modern Sakai, Osaka) to a samurai magistrate of the Sekiyado Domain. He grew up in the city of Noda, Kazusa Province (present day Chiba Prefecture).

Naval career

Suzuki entered the 14th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1884, graduating 13th of 45 cadets in 1887. Suzuki served on the corvettes Tsukuba, Tenryū and cruiser Takachiho as a midshipman. On being commissioned as ensign, he served on the corvette Amagi, corvette Takao, corvette Jingei, ironclad Kongō, and gunboat Maya. After his promotion to lieutenant on 21 December 1892, he served as chief navigator on the corvettes Kaimon, Hiei, and Kongō.[1]

Suzuki served in the First Sino-Japanese War, commanding a torpedo boat and participated in a night torpedo assault in the Battle of Weihaiwei in 1895. Afterwards, he was promoted to lieutenant commander on 28 June 1898 after graduation from the Naval Staff College and assigned to a number of staff positions including that of naval attaché to Germany from 1901 to 1903.[1] On his return, he was promoted to commander on 26 September 1903. He came to be known as the leading torpedo warfare expert in the Imperial Japanese Navy.[2]

During the Russo-Japanese War, Suzuki commanded Destroyer Division 2 in 1904, which picked up survivors of the Port Arthur Blockade Squadron during the Battle of Port Arthur. He was appointed executive officer of the cruiser Kasuga on 26 February 1904, aboard which he participated in the Battle of the Yellow Sea. During the pivotal Battle of Tsushima, Suzuki was commander of Destroyer Division 4 under the IJN 2nd Fleet, which assisted in sinking the Russian battleship Navarin.[2]

After the war, Suzuki was promoted to captain on 28 September 1907 and commanded the destroyer Akashi (1908), followed by the cruiser Soya (1909), battleship Shikishima (1911) and cruiser Tsukuba (1912). Promoted to rear admiral on 23 May 1913 and assigned to command the Maizuru Naval District. Suzuki became Vice Minister of the Navy from 1914 to 1917, during World War I.[2] Promoted to vice admiral on 1 June 1917,[1] he brought the cruisers Asama and Iwate to San Francisco in early 1918 with 1,000 cadets, and was received by U.S. Navy Rear Admiral William Fullam. The Japanese cruisers then proceeded to South America. After stints as Commandant of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy, Commander of the IJN 2nd Fleet, then the IJN 3rd Fleet, then Kure Naval District, he became a full admiral on 3 August 1923. Suzuki became Commander in Chief of Combined Fleet in 1924.[1] After serving as Chief of Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff from 15 April 1925 to 22 January 1929, he retired and accepted the position as Privy Councillor and Grand Chamberlain from 1929 to 1936.

Suzuki narrowly escaped assassination in the February 26 Incident in 1936; the would-be assassin's bullet remained inside his body for the rest of his life, and was only revealed upon his cremation. Suzuki was opposed to Japan's war with the United States, before and throughout World War II.

Prime Minister

On 7 April 1945, Prime Minister Kuniaki Koiso resigned and Suzuki was appointed to take his place at the age of seventy-seven. He simultaneously held the portfolios for Minister for Foreign Affairs and for Greater East Asia.

Prime Minister Suzuki contributed to the final peace negotiations with the Allied Powers in World War II. He was involved in calling two unprecedented imperial conferences which helped resolve the split within the Japanese Imperial Cabinet over the Potsdam Declaration. He outlined the terms to Emperor Hirohito who had already agreed to accept unconditional surrender. This went strongly against the military faction of the cabinet, who desired to continue the war in hopes of negotiating a more favorable peace agreement. Part of this faction attempted to assassinate Suzuki twice in the Kyūjō Incident on the morning of 15 August 1945.

After the surrender of Japan became public, Suzuki resigned and Prince Higashikuni became next prime minister. Suzuki was the Chairman of the Privy Council from 7 August 1944 to 7 June 1945 and again after the surrender of Japan from 15 December 1945 to 13 June 1946.

Suzuki died of natural causes. His grave is in his home town of Noda, Chiba. One of his two sons became director of Japan's immigration service, while the other was a successful lawyer.

Honours

From the corresponding Japanese Wikipedia article

Peerages

- Baron (20 November 1936)

Decorations

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 4th Class (30 May 1905; Sixth Class: 18 November 1895)

- Order of the Golden Kite, 3rd Class (1 April 1906; Fifth Class: 18 November 1895)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (1 April 1916; Second Class: 19 January 1916; Third Class: 1 April 1906)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers (April 29, 1934)

Court order of precedence

- Junior First Rank (August 15, 1960)

Notes

References

- Frank, Richard (2001). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100146-1.

- Gilbert, Martin (2004). The Second World War: A Complete History. Holt. ISBN 0-8050-7623-9.

- Keegan, John (2005). The Second World War. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-303573-8.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kantarō Suzuki. |

- Annotated bibliography for Suzuki Kantarō from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Nishida, Hiroshi. "Imperial Japanese Navy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-13. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- Suzuki Kantarō and Pacific War at 1945 (in Japanese)