Japanese cruiser Naniwa

Naniwa (浪速) was the lead ship of the Naniwa-class protected cruisers, built in the Newcastle upon Tyne-based Armstrong Whitworth Elswick shipyard in the United Kingdom. Together with her sister ship, Takachiho, these were the first protected cruisers acquired by the Imperial Japanese Navy.[1] The name Naniwa comes from an ancient name for Osaka, which appears in the Nara period chronicle Nihon Shoki. She played a major role in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95.

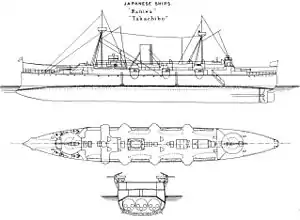

Naniwa in 1887 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Naniwa |

| Ordered: | 1883 Fiscal Year |

| Builder: | Armstrong Whitworth, United Kingdom |

| Laid down: | 27 March 1884 |

| Launched: | 18 March 1885 |

| Completed: | 1 December 1885 |

| Stricken: | 6 August 1912 |

| Fate: | Wrecked 26 June 1912 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Naniwa-class protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 3,650 long tons (3,710 t) |

| Length: | 91.4 m (299 ft 10 in) |

| Beam: | 14 m (45 ft 11 in) |

| Draft: | 6.4 m (21 ft 0 in) |

| Installed power: | 7,604 ihp (5,670 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 18.5 kn (34.3 km/h; 21.3 mph) |

| Range: | 9,000 nmi (17,000 km; 10,000 mi) at 13 kn (24 km/h; 15 mph) |

| Complement: | 325 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

Background

The revolutionary design of the "Elswick" protected cruiser, initially developed as a private-venture by Armstrong Whitworth in the mid-1880s, and implemented in the cruiser Esmeralda for the Chilean Navy (subsequently purchased by Japan as Izumi) was of great interest to Japan because of its high speed, powerful armament, armor protection and relatively low cost, especially since the Imperial Japanese Navy lacked the resources at the time to purchase modern pre-dreadnought battleships.[2] Pioneering Japanese naval architect Sasō Sachū requested that Armstrong Whitworth make modifications to the Esmeralda design to customize it for Japanese requirements, and two vessels, Naniwa and Takachiho were ordered under the 1883 fiscal year budget. When completed, Naniwa was considered the most advanced and most powerful cruiser in the world.[3][4]

Design

The design of Naniwa and Takachiho was based on a steel hull with high freeboard to increase seaworthiness. Compared with Izumi, the armor was stronger and the coal bunkers formed an additional shield around critical areas. The hull was split into multiple watertight compartments, with a double bottom. Both ships were equipped with naval rams as was standard for the time.[5]

Propulsion was by two horizontal two-cylinder double expansion steam engines, with six cylindrical boilers, which provided for a design speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).[5]

As built, her main armament initially consisted of two 260 mm (10.3 in) L/35 Krupp cannons mounted individually on rotating platforms in the bow and stern, with a supply of 200 rounds per gun. Secondary armament was initially six 150 mm (5.9 in) L/35 Krupp cannons mounted in semi-circular sponsons on the main deck, with 450 rounds per gun. Light armament included six QF 6 pounder Hotchkiss guns, ten 1-inch Nordenfelt guns and four 11 mm, 10-barrel Nordenfelt guns.[5] In addition, there were four 356 mm (14.0 in) Whitehead torpedo tubes mounted on the main deck. After the First Sino-Japanese War, both Naniwa and Takachiho were re-armed with eight Elswick QF 6-inch /40 naval guns in order to increase stability and standardize on ammunition for the fleet.

Service record

Early years

Naniwa arrived at Shinagawa, Tokyo on 26 June 1886. She was the first warship purchased by Japan overseas to be brought to Japan with an entirely Japanese crew. Her chief equipping officer was future Admiral Itō Sukeyuki, who oversaw final acceptance testing and was her first captain. During the naval review of February 1887, Emperor Meiji boarded Naniwa in Tokyo, and rode her to Yokohama.

In 1893, Naniwa and Takachiho made two voyages to Honolulu, Hawaii to provide protection for Japanese citizens and to indicate Japanese concern during the Overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy by American marines and colonists. During the second voyage, marines from Naniwa and the Royal Navy's cruiser HMS Champion were asked to land to defend their respective citizens during the "Black Week" hysteria, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii feared invasion by the United States to restore the legitimate government. During the confusion created by the revolution, a Japanese who had been convicted of murder escaped from prison in Honolulu, and sought refuge on Naniwa. Captain Tōgō Heihachirō's refused to hand the convict over to authorities from the Provisional Government, citing that his ship was Japanese territory and that the government of Japan did not recognize the authority of the new government nearly caused a diplomatic incident between Japan and the United States.[6]

First Sino-Japanese War

Prior to the official declaration of war in First Sino-Japanese War, and under the command of Captain (later Fleet Admiral) Tōgō Heihachirō, Naniwa sank the British transport ship Kowshing at the Battle of Pungdo. Kowshing was working under contract for the Imperial Chinese Beiyang Fleet ferrying Chinese reinforcements towards Korea. The sinking caused a diplomatic incident between Japan and Great Britain, but it was recognized by British jurists as being in conformity with international law of the time.[7]

Later in the First Sino-Japanese War, Naniwa was in combat during the critical Battle of the Yalu River, where as part of Admiral Itō Sukeyuki's "flying squadron" including Yoshino, Takachiho and Akitsushima, she assisted in sinking the Imperial Beiyang Fleet cruisers Jingyuan and Zhiyuan. During the battle, Naniwa took a hit from a 210 mm shell, which did virtually no damage.[7]

Naniwa was subsequently used in patrols of the Bay of Bohai and in operations off of Port Arthur. During the Battle of Weihaiwei, she bombarded the coastal forts guarding the Beiyang Fleet navy base.

Naniwa was among the Japanese fleet units that took part in the invasion of Taiwan in 1895, and saw action on 3 June and 13 October 1895, during the respective bombardments of the Chinese coastal forts at Keelung and Takow (Kaohsiung). Her captain at the time was future admiral Kataoka Shichirō.

Interwar years

Naniwa was again sent to Hawaii in a show of force from 20 April – 26 September 1897, when the new Republic of Hawaii banned Japanese immigration and anti-Japanese sentiment appeared to endanger the Japanese population.

Naniwa was re-designated as a 2nd-class cruiser on 21 March 1898, and was based in Taiwan, partly as a counterpoint to the build-up of American forces in Asia during the Spanish–American War. From 1898 to 1900, her role was primarily to patrol the sea lanes between Taipei and Manila. She was subsequently assigned to help cover the landings of Japanese forces in China during the Boxer Rebellion at the end of 1900.

Around 1900–1901, her main battery and secondary battery of Krupp guns was replaced with smaller Elswick QF 6-inch /40 naval guns for stability, and for standardization of ammunition with other ships of the Japanese Navy.

Russo-Japanese War

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, Naniwa was based at Tsushima, and participated in the Battle of Chemulpo Bay, against the forward deployed units of the Imperial Russian Navy in Korea. On 10 March 1904, Takachiho and Naniwa assisted in the blockade of the Russian Pacific Squadron within the confines of Port Arthur and subsequent naval Battle of Port Arthur. During the Battle off Ulsan, Naniwa assisted in the sinking of the Russian cruiser Rurik, and in the rescue of her survivors.[8]

Naniwa was subsequently assigned to the Fourth Division of the Combined Fleet, where she served as the flagship for Rear Admiral Uryū Sotokichi during the crucial Battle of Tsushima, where she took damage on both days of the battle.

Final years and loss

After the end of the Russo-Japanese War, Naniwa was assigned to patrol of the northern seas around Hokkaidō. On 26 June 1912, while on a surveying mission mapping the coastline of the Kurile Islands, she ran aground on the coast of Urup at 46°30′N 150°10′E. Efforts to refloat her were abandoned on 12 July 1912. 'Naniwa' Stuck rock Broton Island Naniwa was officially struck from the navy list on 6 August 1912.[9]

Notes

- Evans, Kaigun, p. 14.

- Brooke, Warships for Export page 58–60

- Evans, Kaigun, p. 15.

- Jentsura, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy

- Chesneau, Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905, p. 226–227.

- Duus, Masayo (2005). The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920. University of California Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-520-20485-9.

- Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy page 133-134

- Howarth, The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun

- Jentsura, p. 95-96.

References

- Brooke, Peter (1999). Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships 1867–1927. Gravesend: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-89-4.

- Chesneau, Roger (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Howarth, Stephen (1983). The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The Drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895-1945. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11402-8.

- Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Paine, S.C.M. (2003). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-61745-6.

- Roberts, John (ed). (1983). Warships of the World from 1860 to 1905 – Volume 2: United States, Japan and Russia. Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Koblenz. ISBN 3-7637-5403-2.

- Roksund, Arne (2007). The Jeune École: The Strategy of the Weak. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15723-1.

- Schencking, J. Charles (2005). Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, And The Emergence Of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868-1922. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4977-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naniwa (ship, 1885). |