Anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia[1] and anti-Japanism) involves the hatred or fear of anything Japanese. Its opposite is Japanophilia.

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Overview

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Neutral | Pos − Neg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

22% | 75% | 3 | -53 | |

39% | 36% | 25 | 3 | |

50% | 32% | 18 | 18 | |

38% | 20% | 42 | 18 | |

45% | 17% | 38 | 28 | |

45% | 16% | 39 | 29 | |

56% | 25% | 19 | 31 | |

57% | 24% | 19 | 33 | |

65% | 30% | 5 | 35 | |

59% | 23% | 18 | 36 | |

58% | 22% | 20 | 36 | |

50% | 13% | 37 | 37 | |

57% | 17% | 26 | 40 | |

65% | 23% | 12 | 42 | |

74% | 21% | 5 | 53 | |

70% | 15% | 15 | 55 | |

78% | 17% | 5 | 61 | |

77% | 12% | 11 | 65 |

| Country polled | Favorable | Unfavorable | Neutral | Fav − Unfav |

|---|---|---|---|---|

4% | 90% | 6% | -86% | |

22% | 77% | 1% | -55% | |

51% | 7% | 42% | 44% | |

78% | 18% | 4% | 60% | |

78% | 16% | 6% | 62% | |

79% | 12% | 9% | 67% | |

80% | 6% | 14% | 74% |

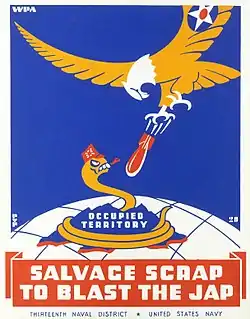

Anti-Japanese sentiments range from animosity towards the Japanese government's actions and disdain for Japanese culture to racism against the Japanese people. Sentiments of dehumanization have been fueled by the anti-Japanese propaganda of the Allied governments in World War II; this propaganda was often of a racially disparaging character. Anti-Japanese sentiment may be strongest in China, North Korea, and South Korea,[4][5][6][7] due to atrocities committed by the Japanese military.[8]

In the past, anti-Japanese sentiment contained innuendos of Japanese people as barbaric. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan was intent to adopt Western ways in an attempt to join the West as an industrialized imperial power, but a lack of acceptance of the Japanese in the West complicated integration and assimilation. One commonly held view was that the Japanese were evolutionarily inferior (Navarro 2000, "... a date which will live in infamy"). Japanese culture was viewed with suspicion and even disdain.

While passions have settled somewhat since Japan's surrender in World War II, tempers continue to flare on occasion over the widespread perception that the Japanese government has made insufficient penance for their past atrocities, or has sought to whitewash the history of these events.[9] Today, though the Japanese government has effected some compensatory measures, anti-Japanese sentiment continues based on historical and nationalist animosities linked to Imperial Japanese military aggression and atrocities. Japan's delay in clearing more than 700,000 (according to the Japanese Government[10]) pieces of life-threatening and environment contaminating chemical weapons buried in China at the end of World War II is another cause of anti-Japanese sentiment.

Periodically, individuals within Japan spur external criticism. Former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi was heavily criticized by South Korea and China for annually paying his respects to the war dead at Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines all those who fought and died for Japan during World War II, including 1,068 convicted war criminals. Right-wing nationalist groups have produced history textbooks whitewashing Japanese atrocities,[11] and the recurring controversies over these books occasionally attract hostile foreign attention.

Some anti-Japanese sentiment originates from business practices used by some Japanese companies, such as dumping.

Region-based Japanophobia

United States

Pre-20th century

In the United States, anti-Japanese sentiment had its beginnings well before the Second World War. As early as the late 19th century, Asian immigrants were subject to racial prejudice in the United States. Laws were passed that openly discriminated against Asians, and sometimes Japanese in particular. Many of these laws stated that Asians could not become citizens of the United States and could not hold basic rights, such as owning land. These laws were greatly detrimental to the newly arrived immigrants, since many of them were farmers and had little choice but to become migrant workers. Some cite the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League as the start of the anti-Japanese movement in California.[12]

Early 20th century

Anti-Japanese racism and Yellow Peril in California had intensified after the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War. On 11 October 1906, the San Francisco, California Board of Education had passed a regulation whereby children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially segregated separate schools. At the time, Japanese immigrants made up approximately 1% of the population of California; many of them had come under the treaty in 1894 which had assured free immigration from Japan.

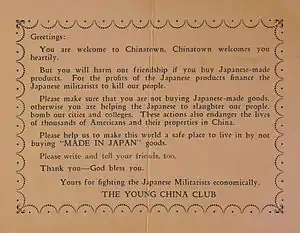

The invasion of China in 1931 and the conquest of Manchuria was roundly criticized in the US. In addition, efforts by citizens outraged at Japanese atrocities, such as the Nanking Massacre, led to calls for American economic intervention to encourage Japan to leave China; these calls played a role in shaping American foreign policy. As more and more unfavorable reports of Japanese actions came to the attention of the American government, embargoes on oil and other supplies were placed on Japan, out of concern for the Chinese populace and for American interests in the Pacific. Furthermore, the European American population became very pro-China and anti-Japan, an example being a grass-roots campaign for women to stop buying silk stockings, because the material was procured from Japan through its colonies.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, Western public opinion was decidedly pro-China, with eyewitness reports by Western journalists on atrocities committed against Chinese civilians further strengthening anti-Japanese sentiments. African American sentiments could be quite different than the mainstream, with organizations like the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World (PMEW) which promised equality and land distribution under Japanese rule. The PMEW had thousands of members hopefully preparing for liberation from white supremacy with the arrival of the Japanese Imperial Army.

During World War II

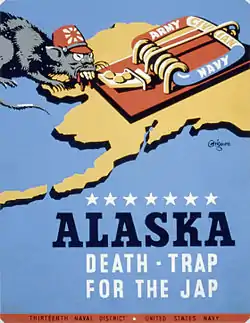

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese attack propelled the United States into World War II. The Americans were unified by the attack to fight against the Empire of Japan and its allies, the German Reich and the Kingdom of Italy.

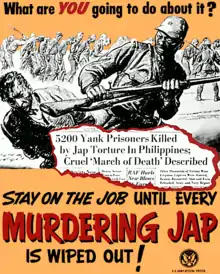

The surprise attack at Pearl Harbor prior to a declaration of war was commonly regarded as an act of treachery and cowardice. Following the attack many non-governmental "Jap hunting licenses" were circulated around the country. Life magazine published an article on how to tell a Japanese from a Chinese person by the shape of the nose and the stature of the body.[13] Japanese conduct during the war did little to quell anti-Japanese sentiment. Fanning the flames of outrage were the treatment of American and other prisoners of war (POWs). Military-related outrages included the murder of POWs, the use of POWs as slave labor for Japanese industries, the Bataan Death March, the kamikaze attacks on Allied ships, and atrocities committed on Wake Island and elsewhere.

U.S. historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in U.S. POW compounds to two key factors: a Japanese reluctance to surrender and a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to POWs."[14] The latter reasoning is supported by Niall Ferguson, who says that "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians [sic] — as Untermenschen."[15] Weingartner believes this explains the fact that a mere 604 Japanese captives were alive in Allied POW camps by October 1944.[16] Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Japanologist, believes that front line troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners, as they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered, got "no mercy" from the Japanese.[17] Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender, in order to make surprise attacks.[17] Therefore, according to Straus, "[s]enior officers opposed the taking of prisoners[,] on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks ..."[17]

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and Japanese Americans from the West Coast were interned regardless of their attitude to the US or Japan. They were held for the duration of the war in the inner US. The large Japanese population of Hawaii was not massively relocated in spite of their proximity to vital military areas.

A 1944 opinion poll found that 13% of the U.S. public were in favor of the genocide of all Japanese.[18][19] Daniel Goldhagen wrote in his book "So it is no surprise that Americans perpetrated and supported mass slaughters - Tokyo's firebombing and then nuclear incinerations - in the name of saving American lives, and of giving the Japanese what they richly deserved."[20]

Decision to drop atomic bombs

Weingartner argues that there is a common cause between the mutilation of Japanese war dead and the decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[21] According to Weingartner both were partially the result of a dehumanization of the enemy, saying, "[T]he widespread image of the Japanese as sub-human constituted an emotional context which provided another justification for decisions which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands."[22] On the second day after the Nagasaki bomb, Truman stated: "The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him like a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true." [16][23]

Since World War II

In the 1970s and 1980s, the waning fortunes of heavy industry in the United States prompted layoffs and hiring slowdowns just as counterpart businesses in Japan were making major inroads into U.S. markets. Nowhere was this more visible than in the automobile industry, where the lethargic Big Three (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) watched as their former customers bought Japanese imports from Honda, Subaru, Mazda, and Nissan, a consequence of the 1973 and 1979 energy crisis. (When Japanese automakers were establishing their inroads into the USA and Canada. Isuzu, Mazda, and Mitsubishi had joint partnerships with a Big Three manufacturer (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) where its products were sold as captives). Anti-Japanese sentiment was reflected in opinion polling at the time, as well as in media portrayals.[24] Extreme manifestations of anti-Japanese sentiment were occasional public destruction of Japanese cars, and in the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese American beaten to death when he was mistaken to be Japanese.

Other highly symbolic deals — including the sale of famous American commercial and cultural symbols such as Columbia Records, Columbia Pictures, 7-Eleven, and the Rockefeller Center building to Japanese firms — further fanned anti-Japanese sentiment.

Popular culture of the period reflected American's growing distrust of Japan. Futuristic period pieces such as Back to the Future Part II and RoboCop 3 frequently showed Americans as working precariously under Japanese superiors. The film Blade Runner showed a futuristic Los Angeles clearly under Japanese domination (with a Japanese majority population and culture), perhaps a reference to the alternate world presented in The Man in the High Castle written by Philip K. Dick, the same author on which the film was based, in which Japan had won World War II. Criticism was also lobbied in many novels of the day. Author Michael Crichton wrote Rising Sun, a murder mystery (later made into a feature film) involving Japanese businessmen in the U.S. Likewise, in Tom Clancy's book, Debt of Honor, Clancy implies that Japan's prosperity is due primarily to unequal trading terms, and portrays Japan's business leaders acting in a power hungry cabal.

As argued by Marie Thorsten, however, Japanophobia mixed with Japanophilia during Japan's peak moments of economic dominance during the 1980s. The fear of Japan became a rallying point for techno-nationalism, the imperative to be first in the world in mathematics, science and other quantifiable measures of national strength necessary to boost technological and economic supremacy. Notorious "Japan-bashing" took place alongside the image of Japan as superhuman, mimicking in some ways the image of the Soviet Union after it launched the first Sputnik satellite in 1957: both events turned the spotlight on American education. American bureaucrats purposely pushed this analogy. In 1982, Ernest Boyer, a former U.S. Commissioner of Education, publicly declared that, "What we need is another Sputnik" to re-boot American education, and that "maybe what we should do is get the Japanese to put a Toyota into orbit."[25] Japan was both a threat and a model for human resource development in education and the workforce, merging with the image of Asian-Americans as the "model minority."

Both the animosity and super-humanizing which peaked in the 1980s, when the term "Japan bashing" became popular, had largely faded by the late 1990s. Japan's waning economic fortunes in the 1990s, known today as the Lost Decade, coupled with an upsurge in the U.S. economy as the Internet took off largely crowded anti-Japanese sentiment out of the popular media.

China

Anti-Japanese sentiment is felt very strongly in China and distrust, hostility and negative feelings towards Japan, Japanese people and culture is widespread in China. Anti-Japanese sentiment is a phenomenon that mostly dates back to modern times (post-1868). Like many Western powers during the era of imperialism, Japan negotiated treaties that often resulted in the annexation of land from China towards the end of the Qing Dynasty. Dissatisfaction with Japanese settlements and the Twenty-One Demands by the Japanese government led to a serious boycott of Japanese products in China.

Today, bitterness in China persists[26] over the atrocities of the Second Sino-Japanese War and Japan's post-war actions, particularly the perceived lack of a straightforward acknowledgment of such atrocities, Japanese government employment of known past war criminals, and Japanese historic revisionism in textbooks. From elementary school, children are taught about Japanese war crimes in detail, for example, thousands of children are brought to the Museum of the War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing by their elementary schools to view photos of war atrocities, such as exhibits of records of Japanese military forcing Chinese workers into wartime labour,[27] the Nanking Massacre,[28] and the issues of comfort women. After viewing the museum, the children's hatred of the Japanese people was reported to increase significantly. Despite the time that has passed since the end of the Second World War, discussions about the Japanese conduct can still evoke powerful emotions today, in part because most Japanese are aware of what happened but their society has never engaged in the type of introspection common in Germany after the Holocaust.[29] Hence, the usage of Japanese military symbols are still controversial in China, such as the incident of Chinese pop singer Zhao Wei seen wearing a Japanese War Flag dress for a fashion magazine photo shoot in 2001.[30] Huge responses were seen on the Internet; a public letter from a Nanking Massacre survivor was sent demanding a public apology, and the singer was even attacked.[31] According to a 2017 BBC World Service Poll, only 22% of Chinese people view Japan's influence positively, with 75% expressing a negative view, making China the most anti-Japanese nation in the world.[2]

Anti-Japanese film industry

Anti-Japanese sentiment can be seen in anti-Japanese war films currently produced and displayed in mainland China. More than 200 anti-Japanese films were made in China in 2012 alone.[32] In one particular situation involving a more moderate anti-Japanese war film, the government of China banned the 2000 film, Devils on the Doorstep, because it depicted a Japanese soldier being friendly with Chinese villagers.[33]

Korea

The issue of anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea is complex and multi-faceted. Anti-Japanese attitudes in the Korean Peninsula can be traced as far back as the Japanese pirate raids and Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), but are largely a product of the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910–1945, and subsequent revisionism in history textbooks used in Japan's educational system after World War II.

Today, issues of Japanese history textbook controversies, Japanese policy regarding World War II, and geographic disputes between the two countries perpetuate this sentiment, and these issues often incur huge disputes between Japanese and South Korean Internet users.[34] South Korea, together with mainland China, may be considered as among the most intensely anti-Japanese societies in the world.[35] Among all the countries which participated in BBC World Service Poll in 2007 and 2009, South Korea and People's Republic of China were the only ones whose majorities rated Japan negatively.[36][37]

Taiwan

The KMT which took over Taiwan in the 1940s held strong anti-Japanese sentiments and sought to eradicate traces of Japanese culture in Taiwan.[38]

During the 2005 anti-Japanese demonstrations in East Asia, Taiwan remained noticeably quieter than the PRC or Korea, with Taiwan-Japan relations regarded at an all-time high. The KMT majority-takeover in 2008 followed by a boating accident resulting in Taiwanese deaths has created recent tensions, however. Taiwanese officials began speaking out on historical territory disputes regarding the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, resulting in an increase in at least perceived anti-Japanese sentiment.[39]

Philippines

Anti-Japanese sentiment traces back to World War II and the aftermath of the war, where an estimated one million Filipinos, of a wartime population of 17 million, were killed during the war, and many more injured. Nearly every Filipino family was hurt by the war on some level. Most notably in the city of Mapanique, survivors recount the Japanese occupation with Filipino men being massacred and dozens of women being herded to be used as comfort women. Today, the Philippines is considered to have un-antagonistic relations with Japan. In addition, Filipinos are generally not as offended as Chinese or Koreans are about the claim from some quarters that these atrocities are given little, if any, attention in Japanese classrooms. It is the result of the huge Japanese aid sent to the country during the 1960s and the 1970s.[40]

Davao in Mindanao had a large population of Japanese immigrants who acted as a fifth column, welcoming the Japanese invaders during World War II. These Japanese were hated by the Moro Muslims and also hated by the Chinese.[41] The Moro juramentados performed suicide attacks against the Japanese, while the Moro juramentados did not ever attack the Chinese since the Chinese were not considered enemies of the Moro people while the Japanese were.[42][43][44][45]

Australia

In Australia, the White Australia policy was partly inspired by fears in the late 19th century that if large numbers of Asian immigrants were allowed, they would have a severe and adverse effect on wages, the earnings of small business people and other elements of the standard of living. Nevertheless, a significant numbers of Japanese immigrants did arrive in Australia prior to 1900 (perhaps most significantly in the town of Broome). By the late 1930s, Australians feared that Japanese military strength might lead to expansion in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, perhaps even an invasion of Australia itself. This resulted in a ban on iron ore exports to the Empire of Japan, from 1938. During World War II atrocities were frequently committed to Australians who surrendered (or attempted to surrender) to Japanese soldiers, most famously the ritual beheading of Leonard Siffleet, which was photographed, as well as incidents of cannibalism and the shooting down of ejected pilots' parachutes. Anti-Japanese feelings were particularly provoked by the sinking of the unarmed Hospital Ship Centaur (painted white and with Red Cross markings), with 268 dead. Treatment of Australians prisoners of war was also a factor, with over 2,800 Australian POWs dying on the Burma Railway alone.

Russian Empire and Soviet Union

In the Russian Empire, the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 halted Imperial Russia's ambitions in the East, leaving them humiliated. Later, during the Russian Civil War, Japan was part of the Allied interventionist forces that helped to occupy Vladivostok until October 1922 with a puppet government under Grigorii Semenov. At the end of World War II, the Red Army accepted the surrender of nearly 600,000 Japanese POWs after Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan on 15 August. Of these, 473,000 were repatriated, with 55,000 having died in Soviet captivity and the fate of the rest being unknown. Presumably, many were deported to China or North Korea to serve as forced laborers and soldiers.[46]

France

Japan's public service broadcaster NHK, which provides a list of overseas safety risks for traveling, in early 2020 listed anti-Japanese discrimination as a safety risk when traveling to France and some other European countries, possibly as a result of fears over the COVID-19 pandemic among other factors.[47] Signs of rising anti-Japanese sentiment in France include an increase in anti-Japanese incidents reported by Japanese nationals, such as being mocked on the street and refused taxi service, and least one Japanese restaurant has been vandalized.[48][49][50] A group of Japanese students on a study tour in Paris received abuse by locals.[51]

Indonesia

In a press release, the embassy of Japan in Indonesia stated that incidents of discrimination and harassment toward Japanese people had increased, possibly related to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 among other factors, and announced they had set up a help center to assist Japanese residents dealing with these incidents.[52] In general, there have been reports of widespread anti-Japanese discrimination and harassment in the country, with hotels, stores, restaurants, taxi services and more refusing Japanese customers, and many Japanese people were no longer allowed in meetings and conferences. The embassy of Japan has also received at least a dozen reports of harassment toward Japanese people in just a few days.[53][54] According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), anti-Japanese sentiment and discrimination has been rising in Indonesia.[55]

Germany

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), anti-Japanese sentiment and discrimination has been rising in Germany.[55]

Media sources have reported a rise in anti-Japanese sentiment in Germany, with some Japanese residents saying suspicion and contempt toward them have increased noticeably.[56] In line with these sentiments, there have been a rising number of anti-Japanese incidents such as at least one major football club kicking out all Japanese fans from the stadium, locals throwing raw eggs at homes where Japanese people live, and a general increase in the level of harassment toward Japanese residents.[57][58][59]

Brazil

Similarly to Argentina and Uruguay, in the 19th and 20th centuries the Brazilian elite desired the racial whitening of the country. The country encouraged European immigration, but non-white immigration always faced considerable backlash. The communities of Japanese immigrants were seen as an obstacle of the whitening of Brazil and were seen as particularly tendentious to form ghettos, had high rates of endogamy, among other concerns. Oliveira Viana, a Brazilian jurist, historian and sociologist described the Japanese immigrants as follows: "They (Japanese) are like sulfur: insoluble". The Brazilian magazine O Malho in its edition of December 5, 1908, issued a charge of Japanese immigrants with the following legend: "The government of São Paulo is stubborn. After the failure of the first Japanese immigration, it contracted 3,000 yellow people. It insists on giving Brazil a race diametrically opposite to ours".[60] On 22 October 1923, representative Fidélis Reis produced a bill on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian [immigrants] there will be allowed each year a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country..."[61]

Some years before World War II, the government of President Getúlio Vargas initiated a process of forced assimilation of people of immigrant origin in Brazil. In 1933, a constitutional amendment was approved by a large majority establishing immigration quotas without mentioning race or nationality, and which prohibited the population concentration of immigrants. According to the constitutional text, Brazil could only receive, at most, a maximum of 2% of the total number of entrants of each nationality that had been received in the last 50 years. Only the Portuguese were excluded from this law. These measures did not affect the immigration of Europeans such as Italians and Spaniards who had already entered in large numbers and whose migratory flow was downward. However, immigration quotas, which remained in force until the 1980s, restricted Japanese immigration, as well as Korean and Chinese immigration.[62][60][63]

When Brazil sided with the Allies and declared war to Japan in 1942, all communication with Japan was cut off, the entry of new Japanese immigrants was forbidden and many restrictions affected the Japanese Brazilians. Japanese newspapers and teaching the Japanese language in schools were banned, leaving Portuguese as the only option for Japanese descendants. As a significant number of Japanese immigrants could not understand Portuguese, it became exceedingly difficult for them to obtain any extra-communal information.[64] In 1939, research of Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil, from São Paulo, showed that 87.7% of Japanese Brazilians read newspapers in the Japanese language, a much higher literacy rate than the general populace at the time.[60] Japanese Brazilians could not travel without safe conduct issued by the police; Japanese schools were closed and radio receivers was confiscated to prevent transmissions on shortwave from Japan. The goods of Japanese companies were confiscated and several companies of Japanese origin had interventions by the government. Japanese Brazilians were prohibited from driving motor vehicles and the drivers employed by Japanese had to have permission from the police. Thousands of Japanese immigrants were arrested or deported from Brazil on suspicion of espionage.[60] On 10 July 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese and German and Italian immigrants who lived in Santos had 24 hours to move away from the Brazilian coast. The police acted without any notice. About 90% of people displaced were Japanese. To reside in coastal areas, the Japanese had to have a safe conduct.[60] In 1942, the Japanese community who introduced the cultivation of pepper in Tomé-Açu, in Pará, was virtually turned into a "concentration camp". This time, the Brazilian ambassador in Washington, D.C., Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, encouraged the government of Brazil to transfer all the Japanese Brazilians to "internment camps" without the need for legal support, in the same manner as was done with the Japanese residents in the United States. However, no single suspicion of activities of Japanese against "national security" was confirmed.[60]

Even after the end of World War II, anti-Japanese sentiment persisted in Brazil. During the National Constituent Assembly of 1946, the representative of Rio de Janeiro Miguel Couto Filho proposed an amendment to the Constitution saying: "It is prohibited the entry of Japanese immigrants of any age and any origin in the country". In the final vote, a tie with 99 votes in favour and 99 against. Senator Fernando de Melo Viana, who chaired the session of the Constituent Assembly, had the casting vote and rejected the constitutional amendment. By only one vote, the immigration of Japanese people to Brazil was not prohibited by the Brazilian Constitution of 1946.[60]

In second half of 2010s, a certain anti-Japanese feeling has grown in Brazil. The current Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, was accused of making statements considered discriminatory against Japanese people, generating repercussions in the press and in the Japanese-Brazilian community,[65] considered the largest in the world outside of Japan.[66] In addition, in 2020, possibly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, cases of xenophobia and abuse were reported to Japanese-Brazilians in cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.[67][68][69]

Yasukuni Shrine

The Yasukuni Shrine is a Shinto shrine in Tokyo, Japan. It is the resting place of thousands of not only Japanese soldiers, but also Korean and Taiwanese soldiers killed in various wars, mostly in World War II. The shrine includes 13 Class A criminals such as Hideki Tojo and Kōki Hirota, who were convicted and executed for their roles in the Japanese invasions of China, Korea, and other parts of East Asia after the remission to them under Treaty of San Francisco. A total of 1,068 convicted war criminals are enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine.

In recent years, the Yasukuni Shrine has become a sticking point in the relations of Japan and its neighbours. The enshrinement of war criminals has greatly angered the people of various countries invaded by Imperial Japan. In addition, the shrine published a pamphlet stating that "[war] was necessary in order for us to protect the independence of Japan and to prosper together with our Asian neighbors" and that the war criminals were "cruelly and unjustly tried as war criminals by a sham-like tribunal of the Allied forces". While it is true that the fairness of these trials is disputed among jurists and historians in the West as well as in Japan, the former Prime Minister of Japan, Junichiro Koizumi, has visited the shrine five times; every visit caused immense uproar in China and South Korea. His successor, Shinzo Abe, was also a regular visitor of Yasukuni. Some Japanese politicians have responded by saying that the shrine, as well as visits to it, is protected by the constitutional right of freedom of religion. Yasuo Fukuda, chosen Prime Minister in September 2007, promised "not to visit" Yasukuni.[70]

Derogatory terms

There are a variety of derogatory terms referring to Japan. Many of these terms are viewed as racist. However, these terms do not necessarily refer to the Japanese race as a whole; they can also refer to specific policies, or specific time periods in history.

In English

- Especially prevalent during World War II, the word "Jap" or "Nip" (short for Nippon, Japanese for "Japan" or Nipponjin for “Japanese person”) has been used in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand as a derogatory word for the Japanese. Tojo is also a racial slur from World War II, but has since died out.

In Chinese

- Riben guizi (Chinese: 日本鬼子; Cantonese: Yaatboon gwaizi; Mandarin: Rìběn guǐzi) – literally "Japanese devils" or "Japanese monsters". This is used mostly in the context of the Second Sino-Japanese War, when Japan invaded and occupied large areas of China. This is the title of a Japanese documentary on Japanese war crimes during WWII. Recently, some Japanese have taken the slur and reversed the negative connotations by transforming it into a cute female personification named Hinomoto Oniko, which is an alternate reading in Japanese.

- Wokou (Chinese: 倭寇; pinyin: wōkòu) – originally referred to Japanese pirates and armed sea merchants who raided the Chinese coastline during the Ming dynasty. The term was adopted during the Second Sino-Japanese War to refer to invading Japanese forces (similarly to Germans being called "Huns"). The word is today sometimes used to refer to all Japanese people in extremely negative contexts.

- Xiao Riben (Chinese: 小日本; pinyin: xiǎo Rìběn) – literally "puny Japan(ese)", or literally "little Japan(ese)". This term is very common (Google Search returns 21,000,000 results as of August 2007). The term can be used to refer to either Japan or individual Japanese people.

- Riben zai (Chinese: 日本仔; Cantonese: Yaatboon zai; Mandarin: Rìběn zǎi) – this is the most common term in use by Cantonese speaking Chinese, having similar meaning to the English word "Jap". The term literally translates to "Japan kid". This term has become so common that it has little impact and does not seem to be too derogatory compared to other words below.

- Wo (Chinese: 倭; pinyin: wō) – this was an ancient Chinese name for Japan, but was also adopted by the Japanese. Today, its usage in Mandarin is usually intended to give a negative connotation. The character is said to also mean "dwarf", although that meaning was not apparent when the name was first used. See Wa.

- Riben gou (Chinese: 日本狗; Cantonese: Yatboon gau; pinyin: Rìběn gǒu) – "Japanese dogs". The word is used to refer to all Japanese people in extremely negative contexts.

- Da jiaopen zu (Chinese: 大腳盆族; pinyin: dà jiǎopén zú) – "big foot-basin race". Ethnic slur towards Japanese used predominantly by Northern Chinese, mainly those from the city of Tianjin.

- Huang jun (Chinese: 黃軍; pinyin: huáng jūn) – "Yellow Army", a pun on "皇軍" (homophone huáng jūn, "Imperial Army"), used during World War II to represent Imperial Japanese soldiers due to the colour of the uniform. Today, it is used negatively against all Japanese. Since the stereotype of Japanese soldiers are commonly portrayed in war-related TV series in China as short men, with a toothbrush moustache (and sometimes round glasses, in the case of higher ranks), huang jun is also often used to pull jokes on Chinese people with these characteristics, and thus "appear like" Japanese soldiers. Also, since the colour of yellow is often associated with pornography in modern Chinese, it is also a mockery of the Japanese forcing women into prostitution during World War II.

- Zi wei dui (Chinese: 自慰隊; Cantonese: zi wai dui; pinyin: zì wèi duì) – a pun on the homophone "自衛隊" (same pronunciation, "self-defense forces", see Japan Self-Defense Forces), the definition of "慰" (Cantonese: wai; pinyin: wèi) used is "to comfort". This phrase is used to refer to Japanese (whose military force is known as "自衛隊") being stereotypically hypersexual, as "自慰隊" means "self-comforting forces", referring to masturbation.

- Ga zai / Ga mui (Chinese: 架仔 / 架妹; Cantonese: ga zai / ga mui) – used only by Cantonese speakers to call Japanese men / young girls. "架" (ga) came from the frequent use of simple vowels (-a in this case) in Japanese language. "仔" (jai) means "little boy(s)", with relations to the stereotype of short Japanese men. "妹" (mui) means "young girl(s)" (the speaker usually uses a lustful tone), with relations to the stereotype of disrespect to female in Japanese society. Sometimes, ga is used as an adjective to avoid using the proper word "Japanese".

- Law baak tau (Chinese: 蘿蔔頭; Cantonese: law baak tau; pinyin: luo bo tou) – "daikon head". Commonly used by the older people in the Cantonese-speaking world to call Japanese men.

In Korean

- Jjokbari (Korean: 쪽발이) – translates as "a person with cloven hoof-like feet".[71] This term is the most frequently used and strongest ethnic slur used by Koreans to refer to Japanese. Refers to the traditional Japanese footwears of geta or tabi, both of which feature a gap between the thumb toe and the other four toes. The term compares Japanese to pigs. The term is also used by ethnic Koreans in Japan.[72]

- Seom-nara won-sung-i (Korean: 섬나라 원숭이) – literally "island country monkey", more often translated as simply "island monkey". Common derogatory term comparing Japanese to the Japanese macaque native to Japan.

- Wae-in (Korean: 왜인; Hanja: 倭人) – translates as "small Japanese person", although used with strong derogatory connotations. The term refers to the ancient name of Yamato Japan, Wae, on the basis of the stereotype that Japanese people were small (see Wa).

- Wae-nom (Korean: 왜놈; Hanja: 倭놈) – translates as "small Japanese bastard". It is used more frequently by older Korean generations, derived from the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598).

- Wae-gu (Korean: 왜구; Hanja: 倭寇) – originally referred to Japanese pirates, who frequently invaded Korea. The word is today used to refer to all Japanese people in an extremely negative context.

Other

- Corona – There have been strong indications that the word "corona" has become a relatively common slur toward Japanese people in several Arabic-speaking countries, with the Japanese embassy in Egypt acknowledging that "corona" had become one of the most common slurs at least in that country,[73] as well as incidents against Japanese aid workers in Palestine involving the slur.[74] In Jordan, Japanese people were chased by locals yelling "corona".[75] Outside of the Arabic-speaking world, France has also emerged as a notable country where use of the new slur toward Japanese has become common, with targets of the slur ranging from Japanese study tours to Japanese restaurants and Japanese actresses working for French companies such as Louis Vuitton.[73][76][77]

See also

- 2012 China anti-Japanese demonstrations

- Japanese-Canadian internment

- Tanaka Memorial

- Japan–Korea disputes

- Anti-Korean sentiment

- Sinophobia

- Anti-Japanese propaganda

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States – The New York Times

- John P. Irish (1843–1923), fought anti-Japanese sentiment in California

- Japanese racial equality proposal, 1919

- United States Executive Order 9066

- Yoshihiro Hattori

References

- Emmott 1993

- "2017 BBC World Service poll" (PDF).

- "Japanese Public's Mood Rebounding, Abe Highly Popular". Pew Research Center. 11 July 2013.

- "World Publics Think China Will Catch Up With the US—and That's Okay". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- "Global Poll Finds Iran Viewed Negatively – Europe and Japan Viewed Most Positively". World Public Opinion.org. Archived from the original on 9 April 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- "POLL: Israel and Iran Share Most Negative Ratings in Global Poll". BBC World Service. 2007. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "24-Nation Pew Global Attitudes Survey" (PDF). The Pew Global Attitudes Project. 12 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- "China's Bloody Century". Hawaii.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "Scarred by history: The Rape of Nanjing". BBC News. 11 April 2005. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- "Budget for the Destruction of Abandoned Chemical Weapons in China". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "China Says Japanese Textbooks Distort History". pbs.org Newshour. 13 April 2005. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- Brian Niiya (1993). Japanese American history: an A-to-Z reference from 1868 to the present (illustrated ed.). Verlag für die Deutsche Wirtschaft AG. pp. M1 37, 103–104. ISBN 978-0-8160-2680-7.

- Luce, Henry, ed. (22 December 1941). "How to tell Japs from the Chinese". Life. Chicago: Time Inc. 11 (25): 81–82. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Weingartner 1992, p. 55

- Niall Fergusson, "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat", War in History, 2004, 11 (2): p.182

- Weingartner 1992, p. 54

- Ulrich Straus, The Anguish Of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II (excerpts) Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003 ISBN 978-0-295-98336-3, p.116

- Bagby 1999, p. 135

- N. Feraru (17 May 1950). "Public Opinion Polls on Japan". Far Eastern Survey. Institute of Pacific Relations. 19 (10): 101–103. doi:10.1525/as.1950.19.10.01p0599l. JSTOR 3023943.

- Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah (2009). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. PublicAffairs. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-7867-4656-9.

- Weingartner 1992, pp. 55–56

- Weingartner 1992, p. 67

- Weingardner further attributes the Truman quote to Ronald Schaffer: Schaffer 1985, p. 171

- Heale, M. J. (2009). "Anatomy of a Scare: Yellow Peril Politics in America, 1980–1993". Journal of American Studies. 43 (1): 19–47. doi:10.1017/S0021875809006033. ISSN 1469-5154.

- Thorsten 2012, p. 150n1

- "China and Japan: Seven decades of bitterness". BBC News, 13 February 2014, accessed 14 April 2014

- " Archived 16 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine"

- "People visit Museum of War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing". Xinhuanet, 27 February 2014, accessed 14 April 2014

- Matthew Forney, "Why China Loves to Hate Japan". Time Magazine, 10 December 2005., accessed 25 October 2008

- "Chinese Pop Singer Under Fire for Japan War Flag Dress". China.org, 13 December 2001., accessed 14 April 2014

- "Chinese Media". Lee Chin-Chuan, 2003., accessed 14 April 2014

- Lague, David (25 May 2013). "Special Report: Why China's film makers love to hate Japan". Reuters. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Forney, Matthew (10 December 2005). "Why China Bashes Japan". TIME. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Munhwa Newspaper (in Korean)". Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- Chun Chang-hyeop (전창협); Hong Seung-wan(홍승완) (8 May 2008). "60th Anniversary of Independence. Half of 20s view Japan as a distant neighbor. [오늘 광복60년 20대 절반 日 여전히 먼나라]". Herald media(헤럴드 경제) (in Korean). Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Israel and Iran Share Most Negative Ratings in Global Poll" (PDF). BBC World service poll. March 2007. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

The two exceptions to this positive reputation for Japan continue to be neighbours China and South Korea, where majorities rate it quite negatively. Views are somewhat less negative in China compared to a year ago (71%[2006] down to 63%[2007] negative) and slightly more negative in South Korea (54%[2006] to 58%[2007] negative).

- "BBC World Service Poll: Global Views of Countries, Questionnaire and Methodology" (PDF). Program on International Policy Attitudes(PIPA). February 2006. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Cheung, Han. "Taiwan in Time: The rehabilitation of Eastern gouache". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Various, Editorials. The Yomiuri Shimbun, 18 June 2008. (in Japanese), accessed 8 July 2008 Archived 20 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Conde, Carlos H. (13 August 2005). "Letter from the Philippines: Long afterward, war still wears onFilipinos". The New York Times.

- Herbert curtis (13 January 1942). "Japanese Infiltration Into Mindanao". The Vancouver Sun. p. 4. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- Filipino Heritage: The Spanish colonial period (late 19th century). Manila: Lahing Pilipino Pub. 1978. p. 1702.

- Filipinas. 11. Filipinas Pub. 2002.Issues 117–128

- Peter G. Gowing (1988). Understanding Islam and Muslims in the Philippines. New Day Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 978-971-10-0386-9.

- Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië. 129. M. Nijhoff. 1973. p. 111.

- "Russia Acknowledges Sending Japanese Prisoners of War to North Korea". Mosnews.com. 1 April 2005. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- "海外安全情報 – ラジオ日本". NHK. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "日本人女性に「ウイルス!」と暴言 志らくが不快感「どこの国でもこういうのが出てくる」(ENCOUNT)". Yahoo!ニュース (in Japanese). Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "「マスクをしたアジア人は恐怖」新型ウィルスに対するフランス人の対応は差別か自己防衛か". FNN.jpプライムオンライン (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- hermesauto (22 February 2020). "'Coronavirus' sprayed on Japanese restaurant in Paris". The Straits Times. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Coronavirus outbreak stokes anti-Asian bigotry worldwide". The Japan Times Online. 18 February 2020. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "新型肺炎に関するセミナーの実施". www.id.emb-japan.go.jp. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "「感染源」日本人に冷視線 入店や乗車拒否 インドネシア(時事通信)". Yahoo!ニュース (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "「日本人が感染源」 インドネシアで邦人にハラスメント:朝日新聞デジタル". 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "「複数国で日本人差別」 外務省、新型コロナ巡り". 日本経済新聞 電子版 (in Japanese). Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "新型コロナウイルス 世界に広がる東洋人嫌悪". Newsweek日本版 (in Japanese). 4 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "'This is racism': Japanese fans kicked out of football match over coronavirus fears". au.sports.yahoo.com. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "いよいよドイツもパニックか 買い占めにアジア人差別 日本人も被害に". Newsweek日本版 (in Japanese). 4 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "ぜんじろう「日本人が全部買い占めてる」欧州でデマ". www.msn.com. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- SUZUKI Jr, Matinas. História da discriminação brasileira contra os japoneses sai do limbo in Folha de S.Paulo, 20 de abril de 2008 (visitado em 17 de agosto de 2008)

- RIOS, Roger Raupp. Text excerpted from a judicial sentence concerning crime of racism. Federal Justice of 10ª Vara da Circunscrição Judiciária de Porto Alegre, November 16, 2001 (Accessed September 10, 2008)

- Memória da Imigração Japonesa Archived May 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- de Souza Rodrigues, Julia; Caballero Lois, Cecilia. "Uma análise da imigração (in) desejável a partir da legislação brasileira: promoção, restrição e seleção na política imigratória".

- Itu.com.br. "A Imigração Japonesa em Itu – Itu.com.br". itu.com.br. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2020/01/ofensa-a-japoneses-amplia-rol-de-declaracoes-preconceituosas-de-bolsonaro.shtml

- http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/nn20080115i1.html

- https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/02/18/national/coronavirus-outbreak-anti-asian-bigotry/#.XorkaIhKjIU

- https://ndmais.com.br/noticias/coronavirus-no-brasil-acende-alerta-para-preconceito-contra-asiaticos/

- https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/leonardo-sakamoto/2020/02/02/surto-de-coronavirus-lembra-racismo-e-xenofobia-contra-orientais-no-brasil.htm

- Blaine Harden, "Party Elder To Be Japan's New Premier", Washington Post, 24 September 2007

- "Definition of Jjokbari". Naver Korean Dictionary.

a derogatory term for Japanese. It refers to Japanese traditional footwear Geta, which separates the thumb toe and the other four toes. [일본 사람을 낮잡아 이르는 말. 엄지발가락과 나머지 발가락들을 가르는 게다를 신는다는 데서 온 말이다.]

- Constantine 1992

- "Coronavirus outbreak stokes anti-Asian bigotry worldwide". The Japan Times Online. 18 February 2020. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "As coronavirus spreads, fear of discrimination rises | NHK WORLD-JAPAN News". NHK WORLD. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "海外安全情報 – ラジオ日本 – NHKワールド – 日本語". NHK WORLD (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- hermesauto (22 February 2020). "'Coronavirus' sprayed on Japanese restaurant in Paris". The Straits Times. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Anti-Asian hate, the new outbreak threatening the world". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

Bibliography

- Bagby, Wesley Marvin (1999). America's International Relations Since World War I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512389-1.

- Constantine, Peter (1992). Japanese Street Slang. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0250-3.

- Emmott, Bill (1993). Japanophobia: The Myth of the Invincible Japanese. Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-1907-6.

- Roces, Alfredo R. (1978). Filipino Heritage: The Spanish Colonial period (Late 19th Century): The awakening. Volume 7 of Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, Alfredo R. Roces. Lahing Pilipino Publishing. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Roces, Alfredo R. (1978). Filipino Heritage: The Spanish colonial period (late 19th century). Volume 7 of Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation. Lahing Pilipino Pub. ; [Manila]. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Navarro, Anthony V. (12 October 2000). "A Critical Comparison Between Japanese and American Propaganda during World War II".

- Schaffer, Ronald (1985). "Wings of Judgement: American Bombing in World War II". New York: Oxford University Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Thorsten, Marie (2012). Superhuman Japan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41426-5.

- Weingartner, James J. (February 1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3640788. S2CID 159919957.

- Filipinas, Volume 11, Issues 117-128. Filipinas Pub. 2002. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, Volume 129. Contributor Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Netherlands). M. Nijhoff. 1973. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

- China's angry young focus their hatred on old enemy

- The Impact of Asian-Pacific Migration on U.S. Immigration Policy

- Kahn, Joseph. China Is Pushing and Scripting Anti-Japanese Protests. The New York Times. 15 April 2005