Japanese dialects

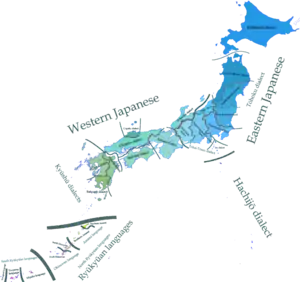

The dialects of the Japanese language fall into two primary clades: Eastern (including Tokyo) and Western (including Kyoto), with the dialects of Kyūshū and Hachijō-jima (Hachijō Island) often distinguished as additional branches, the latter being perhaps the most divergent of all. The Ryukyuan languages of Okinawa Prefecture and the southern islands of Kagoshima Prefecture form a separate branch of the Japonic family, and are not Japanese dialects, although they are sometimes referred to as such.

| Japanese | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Japan |

| Linguistic classification | Japonic

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | nucl1643 |

Map of Japanese dialects (north of the heavy grey line) | |

History

Regional variants of Japanese have been confirmed since the Old Japanese era. Man'yōshū, the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, includes poems written in dialects of the capital (Nara) and eastern Japan, but other dialects were not recorded. The recorded features of eastern dialects were rarely inherited by modern dialects, except for a few language islands such as Hachijō Island. In the Early Middle Japanese era, there were only vague records of dialects, such as notes that "rural dialects are crude". However, since the Late Middle Japanese era, features of regional dialects had been recorded in some books, for example the Arte da Lingoa de Iapam, and the recorded features were fairly similar to modern dialects. The variety of Japanese dialects developed markedly during the Early Modern Japanese era (Edo period), as many feudal lords restricted the movement of people to and from other fiefs. Some isoglosses agree with old borders of han, especially in Tohoku and Kyushu. From the Nara period to the Edo period, the dialect of Kinai (now central Kansai) had been the de facto standard form of Japanese, and the dialect of Edo (now Tokyo) took over in the late Edo period.

With modernization in the late 19th century, the government and intellectuals promoted the establishment and spread of a standard language. Similar to the French policy of vergonha in regards to the Occitan language and the "Welsh Not" of the United Kingdom in regards to the Welsh language, both regional languages and dialects of Japanese were slighted and suppressed in favour of the language of instruction, Standard Japanese, reaching its peak between the 1940s and 1960s, fuelled by Shōwa nationalism and Japan's post-war economic miracle. The policy of language oppression had the effect of creating a sense of shame over the practice of "bad" or "shameful" languages, with some with some teachers administering punishments for the use of non-standard languages, particularly in the Okinawa and Tohoku regions.

Modern day

Following the spread of Standard Japanese throughout the nation, the practice and knowledge of traditional and regional dialects have declined heavily, due to a lack of education, exposure and representation through television, and the concentration of much of Japan's population to its urban centres. However, regional varieties have not been completely replaced with Standard Japanese; the spread of Standard Japanese has seen differing dialects and languages come to be valued as "nostalgic", "heart-warming", and markers of "precious local identity". The decline of the policy of language oppression and shaming has seen many speakers of regional dialects gradually overcome their sense of shame regarding their natural way of speaking. The contact between regional varieties and Standard Japanese has created new regional speech forms among young people, such as Okinawan Japanese.[1][2][3]

Classification

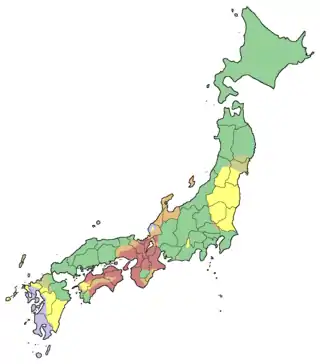

.png.webp)

There are several generally similar approaches to classifying Japanese dialects. Misao Tōjō classified mainland Japanese dialects into three groups: Eastern, Western and Kyūshū dialects. Mitsuo Okumura classified Kyūshū dialects as a subclass of Western Japanese. These theories are mainly based on grammatical differences between east and west, but Haruhiko Kindaichi classified mainland Japanese into concentric circular three groups: "inside" (Kansai, Shikoku, etc.), "middle" (Western Kantō, Chūbu, Chūgoku, etc.) and "outside" (Eastern Kantō, Tōhoku, Izumo, Kyushu, Hachijō, etc.) based on systems of accent, phoneme and conjugation.

Eastern and Western Japanese

A primary distinction exists between Eastern and Western Japanese. This is a long-standing divide that occurs in both language and culture.[lower-alpha 1] The map in the box at the top of this page divides the two along phonological lines. West of the dividing line, the more complex Kansai-type pitch accent is found; east of the line, the simpler Tokyo-type accent is found, though Tokyo-type accents also occur further west, on the other side of Kansai. However, this isogloss largely corresponds to several grammatical distinctions as well: West of the pitch-accent isogloss:[4]

- The perfective form of -u verbs such as "harau" ('to pay') is "harōta" (or minority "haruta"), rather than Eastern (and Standard) "haratta"

- The perfective form of -su verbs such as "otosu" ('to drop') is also "otoita" in Western Japanese (largely apart from Kansai dialect) vs. "otoshita" in Eastern

- The imperative of -ru (ichidan) verbs such as "miru" ('to look') is "miyo" or "mii" rather than Eastern "miro" (or minority "mire", though Kansai dialect also uses "miro" or "mire")

- The adverbial form of -i adjectival verbs such as "hiroi" ('wide') is "hirō" (or minority "hirū") as "hirōnaru", rather than Eastern "hiroku" as "hirokunaru"

- The negative form of verbs is -nu or -n rather than -nai or -nee, and uses a different verb stem; thus "suru" ('to do') is "senu" or "sen" rather than "shinai" or "shinee" (apart from Sado Island, which uses "shinai")

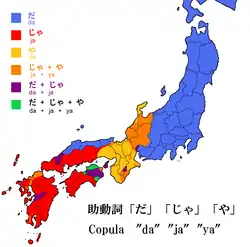

Copula isoglosses. The blue–orange da/ja divide corresponds to the pitch-accent divide apart from Gifu and Sado.

Copula isoglosses. The blue–orange da/ja divide corresponds to the pitch-accent divide apart from Gifu and Sado.

(blue: da, red: ja, yellow: ya; orange and purple: iconically for red+yellow and red+blue; white: all three.) - The copula is da in Eastern and ja or ya in Western Japanese, though Sado as well as some dialects further west such as San'in use da [see map at right]

- The verb "iru" ('to exist') in Eastern and "oru" in Western, though Wakayama dialect uses "aru" and some Kansai and Fukui subdialects use both

While these grammatical isoglosses are close to the pitch-accent line given in the map, they do not follow it exactly. Apart from Sado Island, which has Eastern shinai and da, all of the Western features are found west of the pitch-accent line, though a few Eastern features may crop up again further west (da in San'in, miro in Kyūshū). East of the line, however, there is a zone of intermediate dialects which have a mixture of Eastern and Western features. The Echigo dialect has harōta, though not miyo, and about half of it has hirōnaru as well. In Gifu, all Western features are found apart from pitch accent and harōta; Aichi has miyo and sen, and in the west (Nagoya dialect) hirōnaru as well: These features are substantial enough that Toshio Tsuzuku classifies the Gifu–Aichi dialect as Western Japanese. Western Shizuoka (Enshū dialect) has miyo as its single Western Japanese feature.[4]

The Western Japanese Kansai dialect was the prestige dialect when Kyoto was the capital of Japan, and Western forms are found in literary language as well as in honorific expressions of modern Tokyo dialect (and therefore Standard Japanese), such as adverbial ohayō gozaimasu (not *ohayaku), the humble existential verb oru, and the polite negative -masen (not *-mashinai).[4]

Kyūshū Japanese

Kyūshū dialects are classified into three groups; the Hichiku dialect, the Hōnichi and the Satsugu (Kagoshima) dialect. These dialects have several distinctive features:

- as noted above, Eastern-style imperatives miro ~ mire rather than Western Japanese "miyo"

- ka-adjectives in Hichiku and Satsugu rather than Western and Eastern i-adjectives, as in 'samuka' for "samui" ('cold'), 'kuyaka' for "minikui" ('ugly') and 'nukka' for "atsui" ('hot').

- the nominalization and question particle to except for Kitakyushu and Oita, versus Western and Eastern no, as in 'tottō to?' for "totte iru no?" ('is this taken?') and 'iku to tai' or 'ikuttai' for "iku no yo" ('I'll go').

- the directional particle sai (Standard e and ni), though Eastern Tohoku dialect use a similar particle sa

- the emphatic sentence-final particles tai and bai in Hichiku and Satsugu (Standard yo)

- a concessive particle 'batten' for "dakedo" ('but, however') in Hichiku and Satsugu, though Eastern Tohoku Aomori dialect has a similar particle batte

- /e/ is pronounced [je] and palatalizes s, z, t, d, as in mite [mitʃe] and sode [sodʒe], though this is a conservative (Late Middle Japanese) pronunciation found with s, z ('sensei' [ʃenʃei]) in scattered areas throughout Japan.

- as some subdialects in Shikoku and Chugoku, but generally not elsewhere, the accusative particle o resyllabifies a noun: 'honno' or 'honnu' for "hon-o" ('book'), 'kakyū' for "kaki-o" ('persimmon').

- /r/ is often dropped, for "koi" ('this') versus Western and Eastern Japanese kore

- vowel reduction is frequent especially in Satsugu and Gotō Islands, as in 'in' for "inu" ('dog') and 'kuQ' for "kubi" ('neck').

Much of Kyūshū either lacks pitch accent or has its own, distinctive accent. Kagoshima dialect is so distinctive that some have classified it as a fourth branch of Japanese, alongside Eastern, Western, and the rest of Kyūshū.

Hachijō Japanese

The Hachijō dialects are small group of dialects spoken in Hachijō and Aogashima, islands south of Tokyo, as well as the Daitō Islands east of Okinawa. The Hachijō dialect is quite divergent and sometimes thought to be a primary branch of Japanese. It retains an abundance of inherited ancient Eastern Japanese features.

Notes

- See also Ainu language; the extent of Ainu placenames approaches the isogloss.

References

- Satoh Kazuyuki (佐藤和之); Yoneda Masato (米田正人) (1999). Dōnaru Nihon no Kotoba, Hōgen to Kyōtsūgo no Yukue (in Japanese). Tōkyō: The Taishūkan Shoten (大修館書店). ISBN 978-4-469-21244-0.

- Anderson, Mark (2019). "Studies of Ryukyu-substrate Japanese". In Patrick Heinrich; Yumiko Ohara (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Japanese Sociolinguistics. New York: Routledge. pp. 441–457.

- Clarke, Hugh (2009). "Language". In Sugimoto, Yoshio (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Japanese Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–75. P. 65: "[...] over the past decade or so we have seen the emergence of a new lingua franca for the whole prefecture. Nicknamed Uchinaa Yamatuguchi (Okinawan Japanese) this new dialect incorporates features of Ryukyuan phonology, grammar and lexicon into modern Japanese, resulting in a means of communication which can be more or less understood anywhere in Japan, but clearly marks anyone speaking it as an Okinawan."

- Masayoshi Shibatani, 1990. The languages of Japan, p. 197.

- Pellard (2009), Karimata (1999), and Hirayama (1994)

See also

- Yotsugana, the different distinctions of historical *zi, *di, *zu, *du in different regions of Japan

- Okinawan Japanese, a variant of Standard Japanese influenced by the Ryukyuan languages

External links

| The Wikibook Japanese has a page on the topic of: Dialects |

| Look up Category:Regional Japanese in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japanese dialects. |

- National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (in English)

- 全国方言談話データベース (The conversation database of dialects in all Japan)

- 方言談話資料 (The conversation data of dialects)

- 方言録音資料シリーズ (The recording data series of dialects)

- 『日本言語地図』地図画像 (Linguistic Atlas of Japan)

- 方言研究の部屋 (The room of dialect) (in Japanese)

- 方言ってなんだろう? (What is a dialect?) (in Japanese)

- Kansai Dialect Self-study Site for Japanese Language Learner (in English)

- Japanese Dialects (in English)

- 全国方言辞典 (All Japan Dialects Dictionary) (in Japanese)

- 方言ジャパン