John Grigg (writer)

John Edward Poynder Grigg (15 April 1924 – 31 December 2001) was a British writer, historian and politician. He was the 2nd Baron Altrincham from 1955 until he disclaimed that title under the Peerage Act on the day it received the Royal Assent in 1963.

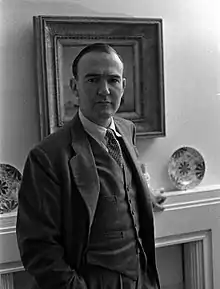

John Grigg | |

|---|---|

Lord Altrincham in 1957 | |

| Born | John Edward Poynder Grigg 15 April 1924 Westminster, London, England |

| Died | 31 December 2001 (aged 77) London, England |

| Pen name | Lord Altrincham (1955–63) |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | New College, Oxford |

| Subject |

|

| Spouse | Patricia Campbell (m. 1958) |

| Children | 2 (both adopted) |

| Relatives | Edward Grigg (father) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1943–1950 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Service number | 302263 |

| Unit | Grenadier Guards |

| Battles/wars | |

Grigg edited the National and English Review (1954–1960) as his father had done. He was a liberal Tory but was defeated at the 1951 and 1955 general elections. In an article for the National and English Review in August 1957, Grigg argued that Queen Elizabeth II's court was too upper-class and British, and instead advocated a more "classless" and Commonwealth court. His article caused a furore and was attacked by the majority of the press, with a minority, including the New Statesman and Ian Gilmour's The Spectator, agreeing with some of Grigg's ideas.

He left the Conservative Party for the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1982.

Early years

Born in Westminster, Grigg was the son of Edward Grigg, 1st Baron Altrincham and his wife, Joan, daughter of politician John Dickson-Poynder, 1st Baron Islington. Edward Grigg was a Times journalist, Liberal, and later Conservative, MP, Governor of Kenya, and member of Winston Churchill's wartime government.[1] His mother organised nursing and midwifery in Kenya.[2]

From Eton, Grigg joined the British Army and was commissioned as a second lieutenant into his father's regiment, the Grenadier Guards, in 1943 during the Second World War (1939–1945). While in the British Army, Grigg served as an officer of the Guard at St James's Palace and Windsor Castle, Berkshire, and saw action as a platoon commander in the 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards, part of the 5th Guards Armoured Brigade of the Guards Armoured Division, against the German Army in France and Belgium. Towards the end of the war, he became an intelligence officer.

After the war, Grigg read Modern History at New College, Oxford. While at Oxford University, he gained a reputation for academic excellence, winning the University Gladstone Memorial Prize in 1948. In the same year, after graduating with second-class honours,[3] Grigg joined the National Review, which was owned and edited by his father.

Political career

A liberal Tory, and later a supporter of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, Grigg sought election to the House of Commons. He stood for election for the recently created Oldham West at the 1951 general election, but was defeated by the sitting member Leslie Hale. Grigg contested the seat again in the 1955 general election but was similarly unsuccessful. With his father's death in December 1955, Grigg inherited the title of Baron Altrincham, which seemingly ended any hope of him being able to stand again as a candidate. Nonetheless, Grigg refused to apply for a writ of summons, abjuring his right to a seat in the House of Lords.

When Tony Benn (the Viscount Stansgate) succeeded in obtaining passage of the Peerage Act, Grigg was the second person (after Benn himself) to take advantage of the new law and disclaim his peerage. In 1997, he wrote that he was "entirely opposed to hereditary seats in Parliament" and added that at that time in 1963 he "felt honour-bound to disclaim, though it was a bore to have to change my name again".[4] Grigg never achieved his ambition of election to the Commons, and he subsequently left the Conservative Party for the SDP in 1982.

Journalism

As his father's health failed during the first few years of the 1950s, Grigg assumed most of the managerial and editorial duties of the now-renamed National and English Review. By the time of his father's death in December 1955, Grigg had taken over the editorship formally, and began to edit the Review into a publication more reflective of his views.[5]

In 1956, Grigg attacked Anthony Eden's Conservative government for its handling of the Suez Crisis, and pressed for an immediate withdrawal of British forces from Port Said. He followed his father in championing reform of the House of Lords, although he added that, in lieu of reform, abolition might be the only alternative. He also advocated the introduction of women priests into the Anglican Church.[5]

Monarchy

In an August 1957 article, "The Monarchy Today",[4] Grigg argued that the court of Queen Elizabeth II was too upper-class and British, and instead advocated a more "classless" and Commonwealth court. More personally, he attacked the Queen's style of public speaking as "a pain in the neck":

"Like her mother, she appears to be unable to string even a few sentences together without a written text – a defect which is particularly regrettable when she can be seen by her audience."[6]

Grigg also criticised the Queen's speeches, normally written for her by her advisers:

"The personality conveyed by the utterances which are put into her mouth is that of a priggish schoolgirl, captain of the hockey team, a prefect, and a recent candidate for Confirmation."[6]

Grigg's article caused a furore and was attacked by the majority of the press, with a minority agreeing with some of his opinions. Henry Fairlie of the Daily Mail accused Grigg of "daring to pit his infinitely tiny and temporary mind against the accumulated experience of centuries".[7] Lord Beaverbrook's Daily Express defended the Queen, and condemned Grigg's article as a "vulgar" and "cruel" attack.[6] Ian Gilmour's The Spectator, whilst agreeing with Grigg's view that the Monarchy leant too heavily on the upper class, accused him of "monarcho-mysticism": exaggerating the influence of the Monarchy, and seeking to elevate the Queen to the position of a "life-force".[7] The Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, also attacked Grigg.[8]

Whilst the BBC censured his views on the Monarchy,[7] Grigg was invited by Granada Television to discuss his article with Robin Day on the programme Impact.[9] As he was leaving Television House having given the interview, a member of the League of Empire Loyalists came up to him and slapped his face,[10] saying:

"Take that from the League of Empire Loyalists."[11]

The man, Philip Kinghorn Burbidge, was fined 20 shillings and said:

"Due to the scurrilous attack by Lord Altrincham I felt it was up to a decent Briton to show resentment. What I feared most was the overseas repercussions and publication in American newspapers. I thought our fortunes were at a low ebb and such things only made them more deplorable."[7]

Burbidge added that the court fine was the best investment he had ever made.[12]

Robert Menzies, the Prime Minister of Australia, was publicly critical of Grigg,[4] describing his article as "disgusting and shocking criticism":

"I think it a very great pity...that it should have been lifted out of a journal with not a very great circulation and given an audience of many millions in the world Press. I think the Queen performs her duties in the Royal office with perfection...If it is now to be said that she reads a speech I might say that many of the great statesmen in the world will have to face the same charge and had better be criticised for it."[13]

Grigg responded, by attacking Menzies for his "disgusting" and "stuffily subservient" attitude towards the Queen, in a front-page interview with the Melbourne Herald:

"Mr Menzies ... is typical of the very worst attitude towards the Crown. He simply blindly worships the Sovereign as someone above criticism...puts her on a pedestal and genuflects."

Grigg alleged that Menzies had given the Queen poor advice during her 1954 tour of Western Australia, when there had been a mild epidemic of poliomyelitis. He said that the risk of the Queen catching polio was minute, when compared to that for the thousands of people who crowded into the streets to see her, but that:

"...as a result of Mr Menzies' advice, the Queen did not shake hands with anyone during the entire visit. She remained remote, aloof and isolated without contact with the people. Bouquets brought to her by little children were taken by her ladies-in-waiting and then thrown in dustbins. The Queen did not spend one night on Western Australian soil and ate only food brought from the liner Gothic. I feel that if the situation was put to her properly she would have seen that it wasn't the way a Sovereign acts".[14][15][16]

Grigg's comments were widely reported across the world.[17] He recorded an interview for Pathé News, reiterating his criticism of the Queen's speeches:

"I feel her own natural self is not allowed to come through: it's a sort of synthetic creature that speaks – not the Queen as she really is."[18]

Grigg also received police protection for his appearance on another Granada broadcast, Youth Wants To Know: this time from Granada Studios in Manchester.[16][19] During the broadcast, he criticised the Queen for taking what he considered to be too many holidays.[20] The Daily Express, having earlier attacked Grigg for his article, began itself to criticise Royal procedure; although it did not criticise the Queen herself.[16]

Reynold's News praised Grigg for "saying out loud what many people are thinking". Kingsley Martin's New Statesman said Grigg had broken the unassailable Fleet Street law:

"...that the Queen is not only devoted, hardworking and young – but also a royal paragon of wit, wisdom and grace."[7]

Grigg always contended that his criticism was meant as constructive, from one who was a reformer and who was a strong believer in constitutional monarchy:

"It is too precious an institution to be neglected. And I regard servile acceptance of its faults as a form of neglect."[5]

Grigg also commented specifically of the Queen:

"She will know that it is easier to be polite to those in high places than to tell them hard truths in a straightforward manner... Wherever she goes, she has the power to help people and to make them happy, simply by being herself. She does not have to pretend to be a Queen: she is the Queen. And the perfect modern Queen is no haughty paragon, but a normal affectionate human being, sublimated through the breadth and catholicity of her experience and the indestructible magic of her office."[17]

Speaking some decades on, Grigg clarified:

"I was rather worried by the general tone of comment, or the absence of comment really in regards to the monarchy – the way we were sort of drifting into a kind of Japanese Shintoism, at least it seemed to me, in which the monarchy was not so much loved as it should be and cherished, but worshipped in a kind of quasi-religious way. And criticism of the people who were actually embodying it at the time was completely out."[21]

In spite of the initial backlash, several of Grigg's recommended reforms for making the monarchy more relevant were accepted by the Royal Household,[22][23] after Grigg's meeting with Martin Charteris, the Queen's assistant private secretary.[24] Debutantes' Parties were ended in 1958,[25] whilst the Queen received help in order to improve her diction before making her Christmas Speech in December 1957.[17] During a meeting at Eton College some decades later, Charteris praised Grigg for his article:

"You did a great service to the monarchy, and I'm glad to say so publicly."[26]

After 1960

The National and English Review closed in June 1960, with its 928th and last issue.[27] At the same time, Grigg started working at The Guardian, which had just relocated to London from its original home in Manchester. For the rest of the decade he wrote a column, entitled A Word in Edgeways, which he shared with Tony Benn.[3]

Work as a biographer and historian

At that same time, in late 1960s, Grigg turned his attention to the project that would occupy him for the remainder of his life: a multi-volume biography of the British prime minister David Lloyd George.[28] The first volume, The Young Lloyd George, was published in 1973. The second volume, Lloyd George: The People's Champion, which covered Lloyd George's life from 1902 to 1911, was released in 1978 and won the Whitbread Award for biography for that year. In 1985 the third volume, Lloyd George, From Peace To War 1912–1916, was published and subsequently received the Wolfson prize. When he died in 2001 Grigg had nearly completed the fourth volume, Lloyd George: War Leader, 1916–1918; the final chapter was subsequently finished by historian Margaret MacMillan (Lloyd George's great-granddaughter) and the book published in 2002. In all the volumes, Grigg showed a remarkable sympathy, and even affinity, for the "Welsh Wizard", despite the fact that their domestic personalities were very different. Historian Robert Blake judged the result to be "a fascinating story and is told with panache, vigour, clarity and impartiality by a great biographer."[29]

Grigg also wrote a number of other books, including: Two Anglican Essays (discussing Anglicanism and changes to the Church of England),[30] Is the Monarchy Perfect? (a compendium of some of his writings on the Monarchy),[31] a biography of Nancy Astor;[32] Volume VI in the official history of The Times covering the Thomson proprietorship;[33] and The Victory that Never Was, in which he argued that the Western Allies prolonged the Second World War for a year by invading Europe in 1944 rather than 1943.[34]

Personal life

Grigg married Belfast native Patricia Campbell, who worked at National and English Review, on 3 December 1958 at St Mary Magdalene Church, Tormarton, Gloucestershire. They later adopted two boys.[35][36]

In popular culture

Grigg is portrayed by John Heffernan in the Netflix series The Crown.[37]

References

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Grigg [née Dickson-Poynder], Joan Alice Katherine, Lady Altrincham (1897–1987), organizer of maternity and nursing services in Africa". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/76425. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Geoffrey Wheatcroft, 'Grigg, John Edward Poynder, second Baron Altrincham (1924–2001)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Jan 2005; online edn, Jan 2011

- Grigg, John (16 August 1997). "Punched, Abused, Challenged". The Spectator. p. 3. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "John Grigg". The Telegraph. 2 January 2002. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "San Bernardino Sun 4 August 1957 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Pimlott, Ben. The Queen. pp. 280, 281.

- "Video: Archbishop of Canterbury reaction to anti-Queen article". Getty Images. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Video: Lord Altrincham interviewed about his controversial article". Getty Images. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Video: Lord Altrincham gets slapped". Getty Images. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- 'Ld. Altrincham Slapped', The Times (7 August 1957), p. 8.

- 'Lord Altrincham's Assailant Fined', The Times (8 August 1957), p. 3.

- "The Sydney Morning Herald - 8th Aug 1957 Page 3". Newspapers.com. 8 August 1957. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Archive, The British Newspaper. "Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail - Thursday 08 August 1957". www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "The Winona Daily News from Winona, Minnesota on August 9, 1957 · Page 2". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "The Singapore Free Press, 9 August 1957, Page 3". 9 August 1957. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- Saunders, Tristram Fane (11 December 2017). "The real Lord Altrincham: the radical hero of The Crown". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- British Pathé (13 April 2014), Peer Raises A Storm (1957), retrieved 11 May 2018

- "Television Programmes - ITV - Youth Wants To Know - Lord Altrincham - Manchester". Getty Images. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo - Aug. 08, 1957 - Lord Altrincham Criticizes The Queen's Holidays During His Appearance On Television". Alamy. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "The World Today - Queen's 80th Birthday marked by popularity". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey (3 January 2002). "John Grigg". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- Halleman, Caroline (8 December 2017). "How Lord Altrincham Changed the Monarchy Forever". Town & Country Magazine. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Lacey, Robert (24 June 2008). Monarch: The Life and Reign of Elizabeth II. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439108390.

- MacCarthy, Fiona (7 July 2011). Last Curtsey: The End of the Debutantes. Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571265817.

- Pearson, John (2011). The Ultimate Family: The Making of the Royal House of Windsor. A&C Black. ISBN 9781448207848.

- "Monthlies". The Spectator Archive. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Lloyd George. Faber & Faber. April 2011. ISBN 9780571277490. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Blake, Robert (28 October 2002). The Evening Standard.

- Grigg, John (1958). Two Anglican essays. London : Secker & Warburg.

- Grigg, John (1958). Is the Monarchy Perfect?. London: J. Calder.

- Grigg, John (1980). Nancy Astor: Portrait of a Pioneer. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0283986314.

- Grigg, John (1993). The History of the Times: Volume VI The Thomson Years 1966–1981. London: Office of the Times. ISBN 978-0723006107.

- Grigg, John (1980). 1943: The Victory That Never Was. London: Eyre Methuen. ISBN 978-0413396105.

- "2nd Baron Altrincham weds Patricia Campbell" alamy.com retrieved 27 April 2017

- "Altrincham, Baron (UK, 1945)" Cracroft's Peerage retrieved 27 April 2017

- Power, Ed (9 December 2017). "The Crown, season 2, episode 5 review: the 'priggish' Queen comes under media attack". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

External links

- "Grigg, John Edward Poynder, second Baron Altrincham". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/76657. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edward Grigg |

Baron Altrincham 1955–1963 |

Disclaimed Title next held by Anthony Grigg |