Kaabu

The Kaabu Empire (1537–1867), also written Gabu, Ngabou, and N'Gabu, was a great empire in the Senegambia region centered within modern northeastern Guinea-Bissau, larger parts of today's Gambia; extending into Koussanar, Koumpentoum, regions of Southeastern Senegal, and Casamance in Senegal. The Kaabu Empire consisted of several languages namely: Balanta, Jola-Fonyi, Mandinka, Mandjak, Mankanya, Noon (Serer-Noon), Pulaar, Serer, Soninke, and Wolof. It rose to prominence in the region thanks to its origins as a former imperial military province of the Mali Empire. After the decline of the Mali Empire, Kaabu became an independent Empire. Kansala, the imperial capital of Kaabu Empire, was annexed by Futa Jallon during the 19th century Fula jihads. However, Kaabu's vast independent kingdoms across Senegambia continued to thrive even after the fall of Kansala; this lasted until total incorporation of the remaining Kingdoms into the British Gambia, Portuguese and French spheres of influence during the Scramble for Africa.

Kaabu Empire Kaabu | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1537–1867 | |||||||||

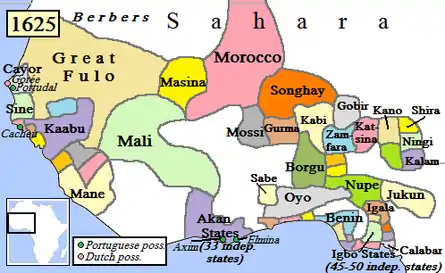

Kaabu Empire circa 1625 (in purple) | |||||||||

| Capital | Kansala | ||||||||

| Common languages | Mandinka | ||||||||

| Religion | Traditional African Religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Kaabu Mansaba | |||||||||

• 1537 - ? | Sama Koli (first) | ||||||||

• 1867 | Janke Waali (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Kaabu Province Founded | 1230s | ||||||||

• Established | 1537 | ||||||||

• Kaabu (Kansala, Capital) Conquered by Futa Jallon | 1867 | ||||||||

| Currency | Cowries | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Tinkuru

The Mandinka arrived in Guinea-Bissau around the year 1200. One of the generals of Sundiata Keita, Tirmakhan Traore, conquered the area, founding many new towns and making Kaabu one of Mali's western tinkuru, or provinces, in the 1230s. By the beginning of the 14th century, much of Guinea-Bissau was under the control of the Mali Empire and ruled by a Farim Kaabu (Commander of Kaabu) loyal to the Mansa of Mali. As in many places that saw Mandinka migrations, much of Guinea-Bissau's native population was dominated or assimilated, resisters being sold into slavery via the trans-Sahara trade routes to Arab buyers. Although the rulers of Kaabu were Mandinka, many of their subjects were from ethnic groups who had resided in the region before the Mandinka invasion. Mandinka became a lingua franca used for trade.

Independence

After the middle of the 14th century, Mali saw a steep decline due to raids by the Mossi to their south and the growth of the new Songhai Empire. During the 16th century, Mali lost many of its provinces reducing it to not much more than the Mandinka heartland. Succession disputes between heirs to Mali's throne also weakened its ability to hold even its historically secure possessions in Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau. Free of imperial oversight, these lands splintered off to form independent kingdoms. The most successful and longest lasting of these was Kaabu, which became independent in 1537. Kaabu's governor, Sami Koli, became the first ruler of an independent Kaabu. He was the grandson of Tiramakhan Traore.

Consolidation of Senegambia

Kaabu carried on the legacy of the Mali Empire much in the same way the Byzantine Empire preserved the culture and social structure of the Roman Empire. The rulers of the Kaabu Kingdom believed their right to rule came from their history as an imperial province. The kings of independent Kaabu discarded the title of Farim Kaabu for Kaabu Mansaba. Among the vast provinces of the Kabu empire included but not limited to Firdu, Pata, Kamako, Jimara, Patim Kibo, Patim Kanjaye, Kantora, Sedhiou, Pakane Mambura, Kiang, Kudura, Nampaio, Koumpentoum, Koussanar, Barra, Niumi, Pacana etc. etc.

Government

Kaabu, despite its ties to Mali, appears to have run in a quite different matter. Mali was established as a federation of chiefs, and the government operated with an assembly of nobles to which the Mansa was largely responsible. Kaabu, however, was established as a military outpost. So it is of little surprise that the kingdom's government was militaristic. The ruling class was composed of warrior-elites made rich by slaves captured in war. These ruling nobles were known from two distinctive sets of clans Koring and Nyancho (Ñaanco). The Korings are (Sanyang and Sonko) whilst the Nyanchos are made up of (Manneh and Sanneh). The militaristic composition of Imperial Kaabu Empire was made up of Korings led by Sanyang Household of Nyambai, with natural allegiance and cousinly support of Sonko Household of Berekolong. The composition of the Koring Military Council's are (Sanyang, Sonko, Manjang, Konjira and Jassey), collective constituting and or aggregating the Koring composition of the Kaabu Empire to a 5 Foothold; and the Nyancho (Sanneh and Manneh) to 2 footholds respectively.

Collectively, Korings and Nyanchos held the power in the state.

Music culture

Mandinka oral tradition holds that Kaabu was the actual birthplace of the Mande musical instrument, known as the Kora. A kora is built from a large calabash cut in half and covered with cow skin to make a resonator, and has a notched bridge like a lute or guitar. The sound of a Kora resembles that of a harp, yet with its gourd resonator it has been classified by ethnomusicologists such as Roderick Knight as a harp-lute.[1] The Kora was traditionally used by the griots as a tool for preserving history, ancient tradition, to memorize the genealogies of patron families and sing their praises, to act as conflict intermediaries between families, and to entertain. Its origins can be traced to the time of the Mali empire and linked with Jali Mady Fouling Diabate, son of Bamba Diabate. According to the griots, Mady visited a local lake in which he was informed that a genie who granted wishes had resided. Upon meeting him, Mady requested that the genie make him a brand new instrument that no griot had ever owned. The genie accepted, but only under the condition that Mady release his sister into his custody. After being informed, the sister agreed to the sacrifice, the genie complied, and hence, the birth of the legendary Kora. Aside from oral testimony, historians propose that the Kora appeared with the apogee of war chiefs from Kaabu, allowing the tradition to spread throughout the Mande area until it was made popular by Koryang Moussa Diabate in the 19th century.

Decline

According to Mandinka tradition, Kabu had been in existence and remained unconquered for eight hundred and seven years. There were 47 Mansas in successions. The power of Kaabu began to wane during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as militant Islamic leaders among the Fula people, with help from some Soninke and Mandinka chiefs, rallied against non-Muslim states in the region. This culminated in 1865 in a regional jihad led by the Imamate of Futa Jallon known as the Turban Kelo or Kansala War. Before then Kaabu had successfully repulsed on numerous occasions various armies at the fort of Berekolong. It was due to Kaabu's decline and its internal infighting that in 1867 Kaabu came under siege from an army led by Alfa Molo Balde, a general from the Imamate of Futa Jallon. After the eleven-day Battle of Kansala, Mansaba Janke Waali Sanneh (also called Mansaba Dianke Walli) ordered the city's gunpowder stores to be set afire. The resulting explosion killed the Mandinka defenders and many of the attackers. Without Kansala, Mandinka hegemony in the region came to an end. The remains of the Kaabu Empire's Imperial capital of Kansala were under Fula control until the Portuguese suppression of the kingdom around the turn of the 20th century.

The resilience of other independent Kingdoms under continued to thrive. They included but not limited to Nyambai, Kantora, Berekolong, Kiang, Wuli, Sung Kunda, Faraba, Berefet etc. (mainly today Gambia and parts of southern Senegal region of cassamance); and other Nyancho controlled areas in Sayjo "Sediou", Kampentum "Koumpentoum", Kossamar "Koussanar" and many parts in today's (Senegal), until the arrival of the British and French colonialist at the turn of 20th Century. To date, the influence of these Korings and Nyanchos are embedded within the socio cultural fabrics of post independent Senegal, Gambia and Guinea Bissau.

See also

References

- "KNIGHTSYSTEM". 2.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

Bibliography

- Boubacar, Barry (1998). Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 388 Pages. ISBN 0-521-59226-7.

- Clark, Andrew F. & Lucie Colvin Phillips (1994). Historical Dictionary of Senegal. Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 370 Pages. ISBN 0-8108-2747-6.

- Lobban, Richard (1979). Historical dictionary of the Republics of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press. pp. 193 Pages. ISBN 0-8108-1240-1.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1999). General History of Africa V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 512 Pages. ISBN 0-520-06700-2.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir. (1989). Histoire des Mandingues de l'Ouest: le royaume du Gabou. KARTHALA Editions. pp. 221 Pages. ISBN 9782865372362.