Mossi Kingdoms

The Mossi Kingdoms, sometimes referred to as the Mossi Empire, were a number of different powerful kingdoms in modern-day Burkina Faso which dominated the region of the upper Volta river for hundreds of years. The kingdoms were founded when warriors from the Mamprusi area, in modern-day Ghana moved into the area and intermarried with local people. Centralization of the political and military powers of the kingdoms begin in the 13th century and led to conflicts between the Mossi kingdoms and many of the other powerful states in the region. In 1896, the French took over the kingdoms and created the French Upper Volta which largely used the Mossi administrative structure for many decades in governing the colony.

Mossi Kingdoms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century–1896 | |||||||

Area occupied by Mossi Kingdoms, c. 1530. | |||||||

| Capital | Multiple capitals | ||||||

| Common languages | Mossi language | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Historical era | Pre-Colonial Africa | ||||||

• Established | 11th century | ||||||

• Conquest by the French colonial empire | 1896 | ||||||

| |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Burkina Faso | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Origin

Accounts of the origin of the Mossi kingdom and parts of their history are very imprecise with contradictory oral traditions that disagree on significant aspects of the story.[1] The origin story is unique in that a woman plays a key role as the progenitor of the royal line.[2]

The origins of the Mossi state are claimed by one prominent oral tradition to come from when a Mamprusi princess left the city of Gambaga because of a dispute with her father. This event dates in different oral histories to be anytime between the 11th and the 15th centuries.[1] According to the story, the princess Yennega escaped dressed as a man when she came to the house of an elephant hunter from the Boussansi tribe named Ryallé. He initially believed she was a man but one day she revealed that she was a woman and the two married. They had a son named Wedraogo or Ouédraogo who was given that name from the horse that Niennega escaped from Gambaga on. Wedraogo visited his grandfather in Dagomba at the age of fifteen and was given four horses, 50 cows, and a number of Dagomba horseman joined his forces. With these forces, Wedraogo conquered the Boussansi tribes, married a woman named Pouiriketa who gave him three sons, and built the city of Tenkodogo. The oldest was Diaba Lompo who founded the city of Fada N'gourma. The second son, Rawa, became the ruler of Zondoma Province. His third son, Zoungrana became the ruler in Tenkodogo after Wedraogo died. Zoungrana married Pouitenga, a woman sent from the chief of the Ninisi tribes, and the resulting intermarriage between the Dagomba, the Boussansi, and the Ninisi produced a new tribe called the Mossi. Zoungrana and Pouitenga had a son, Oubri, who further expanded the kingdom by conquering the Kibissi and some Gurunsi tribes. Oubri, who ruled from around 1050 until 1090 CE, is often considered the founder of the Ouagadougou dynasty which ruled from the capital of Ouagadougou.[1][3]

Rise and centralization

Following Oubri, centralization and small-scale expansion of the kingdoms were the primary tasks. The Ouagadougou dynasty retained control in Ouagadougou, but the other kingdoms established by the sons of Wedraogo retained independence in Tenkodogo, Fada N'gourma, and Zondoma. Under the fifth ruler, Komdimie (circa 1170), two revolutions were started by members of the Ouagadougou dynasty with the establishment of the Kingdom of Yatenga to the north and the establishment of the Kingdom of Rizim. War between Komdimie and Yatenga lasted for many years with Yatenga eventually taking over the independent Mossi state of Zondoma. At the same time, Komdimie created a new level of authority for his sons as Dimas of separate provinces with some autonomy but recognizing the sovereignty of the Ouagadougou dynasty. This system of taking over territory and appointing sons as Dimas would last for many of the future rulers.[3]

Increasing power of the Mossi kingdoms resulted in larger conflicts with regional powers. The Kingdom of Yatenga became a key power attacking the Songhai Empire between 1328 and 1477 taking over Timbuktu and sacked the important trading post of Macina. When Askia Mohammad I became the leader of the Songhai Empire with the desire to spread Islam, he waged a holy war against the Mossi kingdoms in 1497. Although the Mossi forces were defeated in this effort, they resisted attempts to impose Islam. With the conquest of the Songhai by the Moroccans of the Saadi dynasty in 1591, the Mossi states reestablished their independence.[3]

By the 18th century, the Mossi kingdoms had increased significantly in terms of economic and military power in the region. Foreign trade relations increased significantly throughout Africa with significant connections to the Fula kingdoms and the Mali Empire. These relations included military attacks on many times with the Mossi being attacked by a variety of African forces. Although there were a number of jihad states in the region trying to forcibly spread Islam, namely the Massina Empire and the Sokoto Caliphate, the Mossi kingdoms largely retained their traditional religious and ritual practices.[4]

Domestically, the Mossi kingdoms distinguished between the nakombse and the tengbiise. The nakombse claimed lineage connections to the founders of the Mossi kingdoms and the power of naam which gave them the divine right to rule. The tengbiise, in contrast, were considered the people who lived in the region who became assimilated into the kingdoms and would never get access to naam. However, because of their connection to the area they do have tenga which allows them to decide over issues related to land. The rulers' naam and the support of tenga were connected in a two-way dimension of power in society.[1]

Religion

Being located near many of the main Islamic states of West Africa, the Mossi kingdoms developed a mixed religious system recognizing some authority for Islam while retaining earlier ancestor-focused religious worship. The king participated in two great festivals, one focused on the genealogy of the royal lineage (in order to increase their naam) and another of sacrifices to tenga.[2]

In addition, although they had initially resisted Islamic imposition and retained independence from the main Islamic states of West Africa, there began to be a sizable number of Muslims living in the kingdom. In Ouagadougou, the king assigned an Imam who was allowed to deliver readings of the Qur'an to the royalty in exchange for recognizing the genealogical power of the king.[2]

French conquest

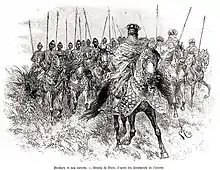

The first European explorer to enter the empire was German Gottlob Krause in 1888. This was followed by a British expedition in 1894 led by George Ekem Ferguson who convinced the Mossi leaders to sign a treaty of protection. Despite this, the French entered the area in 1896 and renounced the treaty of protection to conquer the Mossi Kingdom and make it part of the Upper Volta colony.[3] The French had already conquered or taken over all of the surrounding kingdoms which trapped the Mossi kingdoms.[1] The last king of Ouagadougou, named Wobgo or Wobogoo, was warned a day before the French forces were going to attack the city and so sent a small force to meet them in battle as he fled the city. The French fired four shots in the air which caused the Mossi force to scatter, but Wobgo was able to escape capture. The French made Wobgo's brother, Kouka, the king of Ouagadougou and allied with Yatenga to try and capture Wobgo. When the French and British agreed on the boundary between their colonies, Wobgo lost his main support system and retired with a British pension in Zongoiri in the Gold Coast where he died in 1904.[1][5]

As a result of the significant centralization of the kingdoms, the French largely kept the administration making the Moro-naba in Ouagadougou the primary leader of the region and creating five ministers under him that governed different regions (largely adhering to the Mossi kingdom borders).[3]

Organization

The Mossi kingdoms were organized around five different kingdoms: Ouagadougou, Tenkodogo, Fada N'gourma, and Zondoma (later replaced by Yatenga) and Boussouma. However, there were as many as 19 additional lesser Mossi kingdoms which retained connection to one of the four main kingdoms.[1] Each of these retained significant domestic autonomy and independence but shared kinship, military, and ritualistic bonds with one another. Each kingdom had similar domestic structures with kings, ministers, and other officials and a high degree of centralization of administrative functions. There were prominent rivalries between the different kingdoms, namely between Yatenga and Ouagadougou.[1] Ouagadougou was often considered the primary Mossi kingdom ruled by Moro Naba, but was not the capital of the Mossi kingdoms as each retained autonomy.[1][6]

References

- Englebert, Pierre (1996). Burkina Faso: Unsteady Statehood in West Arica. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Shifferd, Patricia A. (1996). "Ideological problems and the problem of ideology: reflections on integration and strain in pre-colonial West Africa". In Claessen, Henri J.M.; Oosten, Jarich G. (eds.). Ideology and the Formation of Early States. Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill. pp. 24–46.

- Skinner, Elliott P. (1958). "The Mossi and Traditional Sudanese History". The Journal of Negro History. 43 (2): 121–131. doi:10.2307/2715593. JSTOR 2715593.

- Izard, Michel (1982). "La politique extérieure d'un royaume africain: le Yatênga au XIXe siècle (The Foreign Policy of an African Kingdom: Yatenga in the 19th Century)". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 22 (87–88): 363–385. doi:10.3406/cea.1982.3383.

- Lipschutz, Mark R.; Rasmussen, R. Kent (1989). Dictionary of African historical biography. University of California Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-520-06611-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skinner, Elliott P. (1960). "Labour Migration and Its Relationship to Socio-Cultural Change in Mossi Society". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 30 (4): 375–401. doi:10.2307/1157599. JSTOR 1157599.