Yakshagana

Yakshagana is a traditional Indian theatre form, developed in Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, Uttara Kannada, Shimoga and western parts of Chikmagalur districts, in the state of Karnataka and in Kasaragod district in Kerala that combines dance, music, dialogue, costume, make-up, and stage techniques with a unique style and form. It is believed to have evolved from pre-classical music and theatre during the period of the Bhakti movement.[1] It is sometimes simply called "Aata" or āṭa (meaning "the play").[2] This theatre style is mainly found in coastal regions of Karnataka in various forms. Towards the south from Dakshina kannada to Kasaragod of Tulu Nadu region, the form of Yakshagana is called as 'Thenku thittu' and towards north from Udupi up to Uttara Canara it's called as'Badaga Thittu'. Both of these forms are equally played all over the region. Yakshagana is traditionally presented from dusk to dawn. Its stories are drawn from Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagavata and other epics from both Hindu and Jain and other ancient Indic traditions.[3][4]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Sport |

|

Etymology

Yakshagana literally means the people(gana) who are the yaksha (nature spirits).[5] Yakshagana is the scholastic name in Kannada (used for the last 200 years) for art forms formerly known as kēḷike, āṭa, bayalāṭa, and daśāvatāra. The word Yakshagana previously referred to a form of literature primarily in Kannada (starting from the 16th century). Of late Yakshaganas in Tulu and even now in Telugu are available. Performance of this Yakshagana literature or the play is called āṭa. It is now no longer believed that the word Ekkalagaana refers to Yakshagana.

Music genre

Yakshagana has a separate tradition of music, separate from Karnataka Sangeetha and the Hindustani music of India. Yakshagana and Karnatak Sangeetha may have a common ancestor are not decedents of one another.[6]

A typical Yakshagana performance consists of background music played by a group of musicians (known as the himmela); and a dance and dialogue group (known as the mummela), who together enact poetic epics on stage. The himmela is made up of a lead singer (bhagawatha)—who also directs the production—and is referred to as the "first actor" (modalane vesha). Additional himmela members are players of traditional musical instruments, such as the maddale (hand drum), the pungi (pipe), the harmonium (organ), and the chande (loud drums). The music is based on ragas, which are characterised by rhythmic patterns called mattu and tala (or musical meter in Western music).

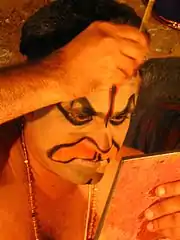

A Yakshagana(ಯಕ್ಷಗಾನ) performance typically begins in the twilight hours, with an initial beating of the drums of several fixed compositions, called abbara or peetike. This may last for up to an hour before the actors finally arrive on the stage. The actors wear resplendent costumes, head-dresses, and face paints.[7]

A performance usually depicts a story from the "Kavya" (epic poems) and the "Puranas" (ancient Hindu texts). It consists of a story teller (the bhagawatha) who narrates the story by singing (which includes prepared character dialogues) as the actors dance to the music, portraying elements of the story as it is being narrated. All components of Yakshagana—including the music, the dance, and the dialogue—are improvised. Depending on the ability and scholarship of the actors, there will be variations in dances as well as the amount of dialogue. It is not uncommon for actors to get into philosophical debates or arguments without falling out of character. The acting in Yakshagana can be best categorised as method acting. The performances have drawn comparison to the Western tradition of opera. Traditionally, Yakshagana will run all night.

Yakshagana is popular in the districts of Dakshina Kannada, Kasaragod, Udupi, Uttara Kannada Shimoga and western parts of chikkamagaluru .[8] Yakshagana has become popular in Bengaluru in recent years, particularly in the rainy season, when there are few other forms of entertainment possible in the coastal districts.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

History

Origins

.jpg.webp)

Yakshagana can refer to a style of writing, as well as the written material itself. It was probably used for poems enacted in bayalaata (or open theatre drama), such as the ballads of Koti and Chennayya. Yakshagana in its present form is believed to have been strongly influenced by the Vaishnava Bhakti movement. Yakshagana was first introduced in Udupi by Madhvacharya's disciple Naraharitirtha. Naraharitirtha was the minister in the Kalinga Kingdom. He also was the founder of Kuchipudi.

The first written evidence regarding Yakshagana is found on an inscription at the Lakshminarayana Temple in Kurugodu, Somasamudra, Bellary District, and is dated 1556 CE. A copy is available at the University of Madras.[9] The inscription mentions land donated to the performers of the art, so as to enable people to enjoy tala maddale programs at the temple. Another important piece of evidence is available in the form of a poem authored by Ajapura Vishnu, the Virata Parva, inscribed on a palm-leaf found at Ajapura (present day Brahmavara).[9] Another historic palm-leaf manuscript, dated 1621 CE, describes Sabhalakshana.[9]

Yakshagana bears some resemblance to other members of the 'traditional theatre family:' Ankhia Nata (found in Assam); Jathra (in Bengal); Chau (Bihar, Bengal); Prahlada Nata (Orissa); Veedhinatakam & Chindu (Andhra); Terukoothu Bhagawathamela (Tamil Nadu), and Kathakali (Kerala). However, some researchers have argued that Yakshagana is markedly different from this group.

Experts have placed the origin of Yakshagana somewhere in the period of the 11th to 16th centuries CE.[10] Yakshagana was an established performance art form by the time of the noted Yakshagana poet, Parthi Subba (c. 1600).[6] His father, Venkata, is attributed by some to be the author of the great Hindu epic, Ramayana, although historian Shivaram Karanth counters these claims (made most notably by historians Muliya Thimmappa and Govinda Pai)[11] and argues that it is Subba, who was in fact its author.[6] Venkata is the probable founder of the tenkuthittu (southern) style of the art.

Troupe centers, such as Koodlu and Kumbala in the Kasaragod District, and Amritheshwari, Kota near Kundapura, claim to have had troupes three to four centuries ago, indicating that the art form almost certainly had begun to take shape by circa 1500.

The Yakshagana form of today is the result of a slow evolution, drawing its elements from ritual theatre, temple arts, secular arts (such as Bahurupi), royal courts of the past, and the artists' imaginations—all interwoven over a period of several hundred years.[10]

Early poets

Early Yakshagana poets included Ajapura Vishnu, Purandaradasa, Parthi Subba, and Nagire Subba. King Kanteerava Narasaraja Wodeyar II (1704–1714) authored 14 Yakshaganas in various languages in the Kannada script.[12][lower-alpha 1] Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar (1794–1868) also wrote several Yakshagana prasanga, including Sougandhika Parinaya.[12][lower-alpha 2] Noted poet, Muddana, composed several Yakshagana prasanga's, including the very popular Rathnavathi Kalyana.

Evolution

In the 19th century, Yakshagana began to move away from the strict traditional forms. Practitioners of the day produced a number of new compositions. Also, a large number of troupes arose across coastal Karnataka.

The early 20th century saw the birth of 'tent' troupes, giving performances to audiences made up of common people who were admitted by ticket. These troupes were responsible for the commercialisation of Yakshagana. The genre saw major changes in form and organisation. Electrical lights replaced the gas lights; seating arrangements improved; the inclusion of folk epics, Sanskrit dramas, and fictional stories formed the modern thematic base of the discipline. Popular entertainment became the criterion, replacing the historic classical presentations. Tulu, the language of the southern part of the Dakshina Kannada and Udupi district's was introduced; increasing popularity with the common people.

At this time, writer Kota Shivaram Karanth, experimented with the dance form by introducing Western musical instrumentation. He reduced the time of a Yakshagana performances from 12 hours to under three hours, incorporated movie plot lines, and added Shakespearean themes.[13] Today, female artists perform in Yakshagana shows.

Parallel forms

Yakshagana is related to other performance art forms prevalent in other parts of Karnataka and the neighbouring states of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra.[14] Yakshagana defies simple classification into categories such as folk, classical, or rural. It can be included in each or all of these, depending upon the rules used for classification. It is more varied and dynamic than most dance forms. Yakshagana can, however, be classified as one of many traditional dance forms. While it prevails primarily in the coastal areas of Karnataka, other dance forms (such as Doddata) are today often called by the same name. Several forms of traditional theatre – Mudalpaya (of southern Karnataka); Doddata (of northern Karnataka); Kelike (on the border with Andhra Pradesh);[15] and Ghattadakore (of Kollegal—in the Chamarajnagar District), may be included in this category. Among them, the Ghattadakore is a direct branch of the coastal form of Yakshagana, while Mudalapaya is the most closely connected form.

Variations and subgenres

Scholars have classified Yakshagana broadly into several types:

- Moodalopaya Yakshagana; includes eastern areas of Karnataka (such as Channarayapattna and Arsikere Taluks of the Hassan District), Nagamangala Taluk of the Mandya District, Turuvekere Taluk of the Tumkur District, Hiriyuru, Challakere of Chitradurga District and North Karnataka.[18]

- Paduvlopaya Yakshagana comprises the western parts of extended Karnataka (including Kasaragod Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Uttara Kannada).

- Tenkutittu (includes areas Kasaragod (Kerala), Mangalore District, Udupi, Sampaaje, Sulliya, Puttur, Bantwala, Belthangady, Karkala, etc.)

- Badagutittu (Udupi to Kundapura area, Uttara Kannada district)

- Badabadagutittu/Uttara Kannadatittu (extreme north parts of Uttara Kannada)[18]

Tenkutittu

One of the traditional variations, the tenkutittu style, is prevalent in Dakshina Kannada, Kasaragod District, western parts of Coorg (Sampaje), and few areas of Udupi district. The influence of Karnatic Music is apparent in tenkutittu, as evidenced by the type of maddale used and in bhaagavathike. Yakshagana is influenced more by folk art blended with classical dance aspects. In tenkutittu, three iconic set of colors are used: the Raajabanna, the Kaatbanna, and the Sthreebanna.

The himmela in the tenkutittu style is more cohesive to the entire production. Rhythms of the chande and maddale coupled with the chakrataala and jaagate of the bhaagavatha create an excellent symphonic sound. The dance form in tenkutittu strikes the attention of the audience by 'Dheengina' or 'Guttu'. Performers often do dhiginas (jumping spins in the air) and will continuously spin (sometimes) hundreds of times. Tenkutittu is noted for its incredible dance steps; its high flying dance moves; and its extravagant rakshasas (demons).

Tenkutittu has remained a popular form and has its own audience outside the coastal areas. The Dharmasthala and Kateelu durgaparameshwari melas (the two most popular melas) have helped to popularise this form. Several creative tenkutittu plays have been composed by noted scholars, such as Amritha Someshwara.[19]

Badagutittu

The Badagutittu style is prevalent in North Canara (Uttara Kannada District) and the northern parts of Udupi Dist from Kundapura to Byndoor, The Badagutittu school of Yakshagana places more emphasis on facial expressions, matugarike (dialogues), and dances appropriate for the character depicted in the episode. It makes use of a typical Karnataka chande.[20]

The Badagutittu style was popularised by Shivram Karanth's, "Yakshagana Mandira," presented at Saligrama Village in Dakshina Kannada as a shorter more modern form of Yakshagana.[20]

Keremane Shivarama Hegde, the founder of the Yakshagana troupe, Idagunji Mahaganapati Yakshagana Mandali, is an exponent of the Badagutittu style of Yakshagana. He is also the first Yakshagana artist to receive the Rashtrapati Award from the president of India. He hails from the Honnavar taluk of Uttara Kannada (North Canara) District.

Puppetry variant

There were more than 30 string-puppet troupes in the undivided Dakshina Kannada district during the period 1910–1915 in places such as Basrur, Barkur, Kokkarne, Mudabidri.[21] The presentation of the puppetry in Yakshagana style is highly stylised and adheres strictly to the norms and standards of Yakshagana. The puppets (generally 18 inches high) wear costumes similar to those worn by live actors of Yakshagana, and have the same elaborate make-up, colorful headgear, and heavy jewellery.[22] The puppeteer is known as the Suthradhara. The content in the Yakshagana puppetry, is also mainly drawn from the ancient epics.[21][22]

Background of puppetry

Yakshagana puppetry has existed for centuries. The modern form of the art, however, was largely moulded by the brothers Laxman, Narasimha, and Manjappa Kamath; who hailed from Uppinakudru village, Kundapur taluk. Devanna Padmanabha Kamath, the grandson of Laxman Kamath infused new life into the art and performed shows all over India. Later, Kogga Devanna Kamath improved this subgenre even further, being recognised with the Tulsi Samman and Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards. His son, Bhaskar Kogga Kamath, is currently performing shows while training others in the art of Yakshagana puppetry.[23] K. V. Ramesh is a leading puppeteer from Kasaragod. He leads the Yakshagana puppet troupe Shri Gopalakrishna Yakshagana Gombeyata Sangha.

Ballet variant

The second half of the 20th century saw experiments and adoptions of this art into other venues. One notable effort was that of Shivarama Karantha, who produced and exhibited Yakshagana ballet, using and training local artists.[24][25] Some of the changes brought about by Karanth, however, attracted criticism.[26] One legal decision even banned any public performance of his experimental ballets being billed as "Yakshagana."

Important components

The artists pray to lord Ganesha before their performance.[27] Yakshagana also ends with a prayer to Ganesha[28]

Raga

Yakshagana Rāga refers to melodic framework used in Yakshagana. It is based on pre-classical melodic forms that comprise a series of five or more musical notes upon which a melody is founded. Ragas in Yakshagana are closely associated with a set of melodic forms called mattu. In the Yakshagana tradition, rāgas are associated with different times of the night throughout which the Yakshagana is performed.

Tala

Yakshagana Tala (Sanskrit tāla) are frameworks for rhythms in Yakshagana that are determined by a poetry style called Yakshagana Padya. Tala also decide how a composition is to be enacted by the dancers. It is similar to tala in other forms of Indian music, but differs from them structurally. Each composition is set to one or more talas, rendered by the himmela percussion artists play.[1][19]

Prasanga and literature

Yakshagana poetry (Yakshagana Padya or Yakshagana Prasanga) is a collection of poems written to form a music drama. The poems are composed in well known Kannada metres, using a frame work of ragas and talas. Yakshagana also has its own metre (or prosody). The collection of Yakshagana poems forming a musical drama is called a Prasanga. The oldest surviving parasanga books are believed to have been composed in the 15th century.[29] But many compositions have been lost to time. There is evidence showing that oral compositions were in use before the 15th century. The narratives of the surviving historic Yakshagana Prasangas are now often printed in paperback.[17]

Costumes and ornaments

Yakshagna costumes are rich in color. The costumes (or vesha) in Kannada depend on characters depicted in the play (prasanga). It also depends on the Yakshagana style (tittu).

Traditionally, Badagutittu Yakshagana ornaments are made out of light wood, pieces of mirror, and colored stones.[30] Lighter materials, such as thermocol, are sometimes used today, although ornaments are still predominantly made of woodwork.

Yakshagana costumes consist of headgear (Kirita or Pagade), Kavacha that decorates the chest, Buja Keerthi (armlets) that decorate the shoulders, and belts (Dabu)—all made up of light wood and covered with golden foil. Mirror work on these ornaments helps to reflect light during shows and add more color to the costumes. Armaments are worn on a vest and cover the upper half of the body. The lower half is covered with kachche, which come in unique combinations of red, yellow, and orange checks. Bulky pads are used under the kachche, making the actors' proportions different in size from normal.

The character, Bannada Vesha, is used to depict monsters. This often involves detailed facial makeup taking three to four hours to complete. Males play the female roles in traditional Yakshagana. However, more recently, yakshagana has seen female artists, who perform in both male and female roles.

The character of Stree Vesha makes use of sari and other decorative ornaments.

Instruments

Maddale

The maddale is a percussion instrument and, along with the chande, is the primary rhythmic accompaniment in the Yakshagana ensemble. It is played in a similar fashion as Mridangam.

Taala (Bells)

Yakshagana bells or cymbals, are a pair of finger bells made of a special alloy (traditionally five metal). They are made to fit the tone of the bhagawatha's voice. Singers carry more than one set, as finger bells are available in different keys, thus enabling them to sing in different pitches. They help create and guide the background music in Yakshagana.

Chande

The Chande is a drum and, along with the maddale, is an important rhythmic accompaniment in the Yakshagana ensemble.

Artists

Over the centuries, hundreds of artists performed Yakshagana and some of them have gained star value, like Siddakatte Chennappa Shetty, Chittani Ramachandra Hegde, Naranappa Uppoor, Balipa Narayana Bhagawat, and Kalinga Navada.

Training and research

As most troupes are associated with temples, training in the art has been confined to temple premises. The Govinda Pai Research Institute, located at MGM College, runs a Yakshagana Kalakendra in Udupi trains youngsters in this ancient dance form. It also does research work on language, rituals, and dance art forms.[31] Srimaya Yakshagana Kalakendra, Gunavante which was founded by Shri Keremane Shambhu Hegde, is another notable Yakshagana Gurukula that trains Yakshagana students .

Outside India

Yakshagana is finding new popularity outside India. Amateur troupes have emerged in California, USA and Ontario, Canada. Yakshamitra in Canada, Yakshagana Kalavrinda, Yaksharanga in the U.S. "Yakshaloka Boston" are a few examples of these international troupes.

Yakshamitra founded in 2008 in Toronto, Canada, is the first full pledged Yakshagana mela outside India. It is the first to use local live music himmela for their performances. The other troupes usually use a recorded background himmela for their shows.

"Yakshaloka USA" was founded in New England by Raghuram Shetty in 1995 and used recorded audio for shows. Being the first build a local Yakshagana troupe ("Yakshaloka Boston") in North America and introduce tenku tiTTu (Southern style) Yakshagana to this continent, he trained thousands of local Americans and inspired 5 Yakshagana troupes (Massachusetts, Washington, Florida, Northern and Southern California). Including shows like Sindh World Conference 2000, AKKA 2002, Saint Peters-burg Folk Festival 2005, Irvine Global Village 2014 etc. Yakshaloka USA has showcased hundreds of multi-lingual shows in major theatres across USA in both styles of Yakshagana. Yakshaloka promotes vibrant ancient Indian art by creating unique shows of its own, presentations in schools and Universities including worlds leading acting schools in Hollywood, training kids and adults from all over the world, joining hands with visiting artists (E.g.: Northern style legend Chittani Ramachandra Hegde troupe 2006), and sponsoring/facilitating leading artists (E.g.: Southern style legend Dr Puttur Shridhara Bhandary 2013).

Yakshagana Kalavrinda performs on the east coast of the U.S. "Yakshaloka Boston" troupe has mainly the artists from Boston area and visiting artists from various parts of USA and India. The troupe has given many shows in the east coast, Midwest, southern USA.

Yaksharanga in the USA started after the visit of Yakshagana artist, Sri Chittani Ramachandra Hegde. His performance at the age of 74 was so inspiring that art lovers decided to continue his art thousands of miles away from its home. Sri Kidayuru Ganesh, who accompanied Sri Chittani, stayed back for a couple of months to train a new generation of Yakshagana artists. The initial result was a performance of Yakshagana "Sudanvarjuna Kalaga". Hegde won the Padmashri Award in 2012 for his lifetime contribution to the art. Yaksharanga has since performed many shows around California.

Yakshagana Troupe, "Shri Idagunji Mahaganapati Yakshagana Mandali, Keremane," headed by Shri Keremane Shambhu Hegde and Shri Keremane Shivanand Hegde, toured the U.S., and performed more than 22 programs throughout North America. The troupe visited 12 countries. This troupe was one of the first few troupes that took Yakshagana (in its traditional form) outside India (referring to their performance at Hilton Hotel, Bahrain in 1983).

Mela or troupes

There are about 30 full-fledged professional troupes, and about 200 amateur troupes in Yakshagana. Professional troupes go on tour between November to May, giving about 180-200 shows. There are about one thousand professional artists and many more amateurs. Further there are off season shows during the wet season, the anniversary shows, school and college students Yakshagana and of course the Talamaddale performances. Yakshagana commercial shows witness 12,000 performances per year in Karnataka generating a turnover of Rs. Six crore.[32][33]

| Town/Village | Date Started | Date of closure (if any) | Main sponsor | Thenkuthittu (T) or Badaguthittu (B) | Free or Ticket |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumble | 19th century | T | Donation | ||

| Karki Hasyagara Mela | 1850s[9] | ||||

| Soukooru Mela | B | ||||

| Kamalashile Mela[9] | still performing | Sri Braahmi Durgaparameshwari Temple | B | Donation | |

| Halady | 1980s | Still performing | Halady temple | B | Free/donation |

| Saligrama | 1980s | Still performing | B | Ticket | |

| Amrutheswari | Early 20th century | Still performing | Amrutheswari temple | B | Ticket |

| Makkala Mela[9] | 1973 | Saligrama | |||

| Dharmasthala Mela | 19th century | still performing | Sri Kshetra Dharmasthala | T | Devotees' donation |

| Kudlu Kutyala Mela | T | ||||

| Suratkal Mela | T | ||||

| Ranjadakate mela | B | From Shimoga Dist. | |||

| Goli Garadi[9] | Koti Chennaya Garadi | B | Sasthana | ||

| Kateel Mela | 1867[34] | still performing | Kateel Shri Durgaparameshwari Temple | T | |

| Idugunji Mela[9] | 1934 | still performing | B | Donation/Tickets | |

| Hosanagara Mela | still performing | T | |||

| Perduru Mela[9] | 1983–1984 | still performing | Sri Anathapadhmanaabha Temple | B | Ticket |

| Kondadakuli Mela | B | Ticket | |||

| Maranakatte mela[9] | still performing | Sri Brahmalingeshwara Temple | B | Donation, Devotee | |

| Mandarthi Mela[9] | 1950s | still performing | Durgaparameswari Temple | B | Devotees' donation |

| Keremane Mela | B | ||||

| Bappanadu Mela | Bappanadu Durgaparameshwari Temple, Mulki | T | |||

| Yakshamitra Yakshagana Mela Toronto (www.yakshamitra.com) | Dec 2008, New Market, ON | Sringeri Vidhyabharathi Temple, Etobicoke. | Badagu | Ticket and Free when sponsored. |

- Characters found in Yakshagana

Raghuram Shetty Yakshaloka USA

Raghuram Shetty Yakshaloka USA Prathibha Raghuram Shetty Yakshaloka USA Indrajitu Villain

Prathibha Raghuram Shetty Yakshaloka USA Indrajitu Villain Kondadakuli

Kondadakuli Madana Vesha

Madana Vesha Thulu Yakshagana

Thulu Yakshagana Bhima in Yakshagana

Bhima in Yakshagana Jambavanta as depicted in Yakshagana

Jambavanta as depicted in Yakshagana Krishna - Keremane Shivanand Hegde

Krishna - Keremane Shivanand Hegde Gajamukhadavage Ganapage

Gajamukhadavage Ganapage Sharanu Bande Guruve

Sharanu Bande Guruve Bannada Vesha

Bannada Vesha Yakshagana player in costume

Yakshagana player in costume Poothini

Poothini Veerabhadra (Thenkuthittu)

Veerabhadra (Thenkuthittu)

- Yakshagana related photos

Pundu Vesha with Pagade or Kedige Mundale (Kambalashwa photo)

Pundu Vesha with Pagade or Kedige Mundale (Kambalashwa photo) Akrura vesha

Akrura vesha Akrura

Akrura Bannada Vesha

Bannada Vesha Badaguthittu vesha

Badaguthittu vesha Chowki, the greenroom of Yakshagana, where artists get themselves ready

Chowki, the greenroom of Yakshagana, where artists get themselves ready Parvathi artist

Parvathi artist Full Pagade vesha in Yakshagana

Full Pagade vesha in Yakshagana Hanumantha

Hanumantha Hanumantha on last leg of Makeup.

Hanumantha on last leg of Makeup. A performance artist troupe of the Yaksharanga variant

A performance artist troupe of the Yaksharanga variant Maisasura in Kateel Mela

Maisasura in Kateel Mela

See also

- Kabuki, a visually similar form of Japanese theatre.

Notes

- This King of Mysore was deaf and dumb, but knew several languages.

- Mysore kings often gave patronage to various forms of performance artists

References

- Prof. Sridhara Uppura; 1998; Yakshagana and Nataka Diganta; publications.

- "The changing face of Yakshagana". Online webpage of The Hindu. Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Ashton, Martha Bush (3 January 1976). "Yakshagana". Abhinav Publications – via Google Books.

- http://kasargod.nic.in/profile/yakshagana.htm

- "yaksha". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Dr. Shivarama Karantha; Yakshagana Bayalaata; Harsha Publications; 1963; Puttur, South Canara, India.

- Yakshagana; accessed 2 November 2013

- "Yakshagana".

- Martha Bush Ashton, Bruce Christie (1977). Yakshagana, a Dance Drama of India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 21,22. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- "The Hindu- Focus on rural art". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 23 December 2005. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Note: This due to what Karantha describes as procedural lapses in their research and conclusions. Karantha bases his claim on the fact that Venkata was reported to be a bhagawatha (singer) himself, and is believed to have founded his own troupe.

- Pranesh, Meera Rajaram (2003) [2003]. Musical Composers during Wodeyar Dynasty (1638–1947 A.D.). Bangalore: Vee Emm. pp. 37, 38.

- Hapgood, Robert; 1983; Macbeth Distilled: A Yakshagana Production in Delhi]; "Shakespeare Quarterly;" Vol. 31; No. 3; Autumn, 1980; pp. 439-440.

- Growing with Tradition; 14 October 2005 article; Hindu.com; accessed November 2013

- http://www.rangashankara.org/home/rangatest/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=18&Itemid=32&favm=2010-11-1

- "3-day festival to celebrate Karanth's birth centenary". The Times of India. 20 December 2002. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Brandon, James R., ed. (28 January 1997). The Cambridge guide to Asian Theatre (1997 (2nd reprint) ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 115, 116. ISBN 9780521588225.

- Dr. Achar, Palthady Ramakrishna; 2004; Janapada Parisara; Puttur; "Supriya Prakashana;" p.68

- "Tenkuthittu".

- Classical Indian Dance Directory; Narthaki.com; accessed November 2013.

- Dr. A Sundara. "Pre historic art in Karnataka".

- Gosh, Banerjee, Sampa, Utpal Kumar; Banerjee, Utpal K. (2006). Indian puppets. New Delhi: Abhinav publications. p. 78. ISBN 9788170174356. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "Award for achievement". Online webpage of The Hindu. Chennai, India: The Hindu. 7 March 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- K.S., Upadhyaya (12 May 2001). "Sri Naranappa Uppooru". Udupi: Yakshagana.com. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Kota Shivarama Karanth (1 January 1997). Yakṣagāna. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-357-1. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- "Seminar on Karanth".

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande (1987). History of Indian Theatre, Volume 2. ISBN 9788170172789.

- "Yakshaganam, Kasaragod, Kerala, India | Kerala Tourism".

- Prof Sridhara Uppura; Diganta Sahitya publications; Managalore; 1998.

- Yakshagana Costumes of Karnataka; "The Craft and Artisans"; accessed November 2013

- "Archive News". The Hindu.

- "Open study-chairs for research on Yakshagana". Online webpage of The Hindu. Chennai, India: The Hindu. 9 July 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- "Traditional touch in theatre". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- http://portal.kinnigoli.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3066&catid=13:english-fiction&Itemid=37

Further reading

- Ashton, Martha Bush; Yakshagana; published by Abhinav Publications; India; 1st edition (15 June 2003); ISBN 81-7017-047-8 and ISBN 978-81-7017-047-1

- Rao, Neelavara Lakshminarayan & Patil, Gorpadi Vittala; Yakshagana Swabodhini; published by: Yakshagana Kendra; MGA College; Udupi, India; 1st edition.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yakshagana. |