Knanaya

The Knānāya, (from Syriac: Knā'nāya (Canaanite)) also known as the Southists or Tekkumbhagar, are an endogamous ethnic group found among the Saint Thomas Christian community of Kerala, India. They are differentiated from another part of the community, known in this context as the Northists (Vaddakkumbhagar). There are about 300,000 Knanaya in India and elsewhere.[1]

Knānāya Diaspora of Ancient Malabar | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| c. 300,000 (Kerala, India; USA; elsewhere) | |

| Languages | |

| Malayalam; local languages

Liturgical: Syriac Written: Suriyani Malayalam | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Saint Thomas Christians, Malayalis, Cochin Jews |

The origins of the division of the Saint Thomas Christians into Northist and Southist groups is traced back to the arrival of the Syrian merchant Thomas of Cana (Knāi Thoma) who led a migration of Syriac Christians (Jewish-Christians) from Mesopotamia to India in the 4th or 8th century. The Knanaya claim descent from Thomas of Cana and those who came with him. The communities arrival was recorded on the Thomas of Cana copper plates which existed in Kerala until the 17th century after which point they were taken to Portugal by the Franciscan Order. The ethnic division between the Knanaya and other St. Thomas Christians was observed during the Portuguese colonization of India in the 16th century and was noted throughout the European colonial era.

Today, the majority of Knanaya are members of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church (Kottayam Archeparchy) and the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church (Knanaya Archdiocese). They became increasingly prominent in Kerala in the late 19th century. Many Knanaya migrated away during the 20th and 21st centuries, largely westward, forming communities in non-Malayalam speaking areas, with a large expatriate community currently living in Houston, Texas and Chicago, Illinois in the United States.

Etymology

The term Knānāya derives from the name Knāi Thoma (anglicized as Thomas of Cana), an important figure in the Saint Thomas Christian tradition.[2] The term is derived from Thomas' Syriac adjectival epithet Knā'nāya in reference to the land of Canaan, meaning Canaanite.[3] The earliest written record of the term used as a designation of the community dates to the 1800s,[4][3] however notations of the term itself are found in Knanaya folk songs such as the song of the erection of Kallisserry Church in 1580.[5][3] Additionally the term is also found translated as "Cananeo" in Bishop Francis Ros' text MS. ADD. 9853 in 1604 and Portuguese historian Diogo Do Couto's text Decada XII in 1611.[3][6] Members of the Knanaya Community are also generally called Knāi or Knā, in reference to Thomas. Many Knanaya families, especially those of the Kaduthuruthy region maintain the surname Kinān, a derivative of Thomas' epithet. Woman of these families preserve gendered forms of the term, examples of this being Kināti Anna, Kināti Mariam, etc.[7]

The ultimate derivation of Thomas' English epithet Cana is not clear: it may refer to the town of Cana, which is mentioned in the Bible, or it may instead refer to the land of Canaan.[2]Alternately, it may be a corruption of a Syriac term for merchant (Knāyil in Malayalam).[8] However, scholar Richard M. Swiderski states that none of these etymologies are entirely sound.[2] Knanaya priest and pontifical scholar Dr. Jacob Kollaparambil argues that the "Cana" form is a corruption introduced by European scholars in the 18th century based on the Malayalam form Knāy and its variants (Knāi, Kinān, Knāyi) found in the folk tradition of the Knanaya and the common parlance and literature of the people of Malabar.[9] This may be a reference to the Christian community of Kynai, in Bét Aramayé in Persia, a historical center of Syriac Christianity.[7]

The Knanaya are also known as Tekkumbhagar in Malayalam; this is generally translated into English as "Southist", or sometimes "Southerner" or "Suddhist". This is in reference to the historically significant geographical division between them and other Saint Thomas Christians, who are known as Vadakumbhagar or Northists in this context.[10]

Titles

Historically the Knanaya held the title of being the "protectors of seventeen castes", an authority given to them by the Cheraman Perumal according to folk tradition. This title which was reflective of the historical high socio-economic status of the Knanaya, is to this day exhibited during Knanaya marriage ceremonies when individuals taking part in the rituals ask permission before fulfilling their designated role. A prominent example of this is seen during the "Chandam Charthal" or grooms beautification ceremony, in which the barber petitions the assembly three times with the following request: "I ask the gentlemen here who have superiority over 17 castes, may I shave the bridegroom?".[11]

The Knanaya were also known as Ancharapallikar or the "Owners of Five and a Half churches" a title reflective of the five churches owned by the Southist Community before the Synod of Diamper in 1599. The churches are listed as the following: Udayamperoor, Kaduthuruthy, Kottayam, Chunkom, and Kallissery. The "half church" is a reference to the half privilege and share the Knanaya held in other churches they co-owned with the Northist St. Thomas Christians, usually in areas where not many Knanaya lived.[12]

History

Origins and traditions

The earliest extensive written evidence for the division of the Christian community of India dates to the 16th century.[13] The St. Thomas Christian tradition defines the division as being both geographical and ethnic, expressing that the Native St. Thomas Christians initially resided on the north side of the Chera Empire's capitol city of Cranganore while the Middle Eastern migrant Knanaya arrived and settled on the south side, which subsequently led to the designations Northist and Southist.[14][15] Celebrated St. Thomas Christian scholar Dr. Placid J. Podipara wrote the following about the division:

"The Thomas Christians hail the Apostle St. Thomas as the founder of their Church...The first converts of St. Thomas were reinforced by local conversions and by Christian colonizations (migrations) from abroad. Connected with the IV century colonization is the origin of those called the Southists"[16]

Directional divisions within communities are common in Kerala, including among Hindu groups.[17][18] A similar north–south division is found among the Nairs, and it historically appears to have been in place in the early Brahmin settlements in the area. The Saint Thomas Christians may have taken this trait from the Brahmins.[19]

Thomas of Cana's Arrival

The historical rationale for the division between the majority St. Thomas Christians and minority Knanaya traces the divide to the figure of Thomas of Cana, a Syrian merchant who led a group of 72 Jewish-Christian immigrant families, a bishop named Uraha Mar Yausef, and clergymen from Mesopotamia to settle in Cranganore, India in the 4th century (some sources place these events as late as the 9th century).[20][21][22] This may reflect a historical migration of East Syrian Christians to India around this time, which established the region's relationship with the Church of the East.[23]In the commonly accepted accounts of this history, the Knanaya are the descendants of Thomas of Cana and his followers, while the Northists descend from the local Christian body which had been converted by Thomas the Apostle centuries earlier.[24][25][14][26][27][16] The Oxford History of the Christian Church states the following about the division:

"In time, Jewish Christians of the most exclusive communities descended from settlers who accompanied Knayil Thomma (Kanayi) became known as ‘Southists’ (Tekkumbha ̄gar)...They distinguished between themselves and ‘Northists’ (Vatakkumbha ̄gar). The ‘Northists’, on the other hand, claimed direct descent from the very oldest Christians of the country, those who had been won to Christ by the Apostle Thomas himself. They had already long inhabited northern parts of Kodungallur. They had been there even before various waves of newcomers had arrived from the Babylonian or Mesopotamian provinces of Sassanian Persia."[28]

.jpg.webp)

Elements of Thomas of Cana's arrival feature in ancient songs as well as the Thomas of Cana copper plates awarded to his followers by a local Hindu ruler. [29][30][22][31] These plates granted Thomas' followers 72 social, economic, and religious rights from Cheraman Perumal, the Chera king.[32] [29][33] [34] The plates were present in Kerala during the time of the Portuguese colonization in the early 17th century, but were lost during Portuguese rule.[35][33] [29] [34] Archbishop Francis Ros notes in his 1604 account M.S. ADD 9853 that the plates were taken to Portugal by the Franciscan Order.[36] The Knanaya invoke the plates as evidence of their descent from Thomas of Cana's mission.[37]

.jpg.webp)

Translations of the existing Kollam Syrian Plates of the 9th century made by the Syrian Christian priest Ittimani in 1601 as well as the French Indologist Abraham Anquetil Duperron in 1758 both note that the forth plate mentioned a brief of the arrival of Knai Thoma.[29][38]It is believed that this was a notation of the previous rights bestowed upon the Christians by Cheraman Perumal.[38] The contemporary forth plate however does not mention this paragraph and is believed to be a later copy. Scholar of Early Christian history Istavan Percvel theorizes that at one time the Kollam Syrian plates and the Thomas of Cana plates were kept together.[29]

Jewish-Christian Ancestry

Knanaya tradition states that the Syriac Christian migrants who arrived with Thomas of Cana were Jewish-Christians. Community scholars express the historicity of this tradition by noting that Jewish-Christian tribes in Mesopotamia were a major component of the early Church of the East.[39] Additionally, scholars express that both Jewish and Christian merchants of the region took part in the Arabian Sea trade with Kerala.[39]

The community also cites their culture as evidence of their Jewish-Christian heritage, particularly their folk songs first written on palm-leave manuscripts in the 17th century. Many of the historical songs allude to the migrants being of Jewish descent such as the song Nallor Orosilam (The Good Jerusalem) which states the migrants prayed at the tomb of the Jewish Prophet Ezra before departing to India.[39] A number of Jewish scholars such as Dr. P.M. Jussay, Dr. Nathan Katz, Dr. Shalva Weil, and Dr. Ophira Gamliel have noted that the Knanaya maintain cultural similarities to the Cochin Jews of India,[33][40][41]suggesting historic cultural relations between the two communities.[42]

In 1939, the Knanaya politician and author Joseph Chazhikaden published a book on the community, Tekkumbhagasamudayam Charitram, in which he included some aspects of the communities Jewish claim. Chazhikaden built upon the Thomas of Cana tradition but asserted that Thomas' followers originated in Judea. According to Chazhikaden, the group converted to Christianity while maintaining their distinct culture and identity.[43] Eventually, they were forced out of their homeland and moved to Cranganore, where they were welcomed by the ruler Cheraman Perumal and lived near, but maintained their separateness from, the indigenous "Northist" Saint Thomas Christians. Many modern Knanaya accept the account as factual, while others reject it. As with other Knanaya origin traditions, some Northists dispute and condemn it.[44]

Two Wives Legend

In many other variants recorded during the colonial era, Thomas of Cana had two wives or partners, one of them being the ancestor of the endogamous Southists, and the other one being the ancestor of the Northist.[17][25] A number of traditions and stories have emerged to explain the status of either wife,[45] and both Southists and Northists historically used variants of these traditions to claim superiority for their group.[20] These variants are considered apocryphal and are not the accepted tradition among contemporary Northist and Southist scholars who generally believe them to be the consequence of rivalry between the St. Thomas Christians and Knanaya.[14] In most of these variants, the Southists' ancestor was Thomas' Syrian wife, while the Northists' was an indigenous St. Thomas Christian or Nair woman who became his second wife or concubine, implying that the Southists are Thomas' true heirs.[46] In other variants, both wives were Kerala natives, while the Southists' forebearer was from a higher caste.[47]

Some Northist historically maintained versions which countered this assertion, claiming that the Knanaya descend from a dobi (washerwoman); in some versions of this story, she became Thoma's concubine, while in others she married a lower-caste Maaran boy.[48] This assertion is based on the 1676 Portuguese document "M.S Sloane 2748-A", a likely forgery attributed to the Carmelite priest Father Mathew.[49]

Historian of medieval India and Northist priest Pius Malekandathil argues that the two-wives legend was simply a creation of rivalry between the Middle Eastern migrant Knanaya and the Native St. Thomas Christians. Malekandathil expresses that the story originated in the medieval era due to the two ethnic groups of Christians asserting socioeconomic dominance over the other. Furthermore, Malekandathil notes that the two-wives legend is not the accepted tradition among the people of Kerala but instead that the indigenous Saint Thomas Christians got the appellation "Northists" because they were initially located on the northern part of the city of Cranganore, while the migrant Knanaya under the leadership of Thomas of Cana were given the southern side of the city which led to the generic title of "Southists".[14]

Late Medieval Era

The first written evidence of a Knanaya individual dates to the year 1301, with the writings of Zacharias the deacon of St. Kuriakose Church, Cranganore.[50] Historically the Knanaya had a township and three churches namely of Saint Thomas the Apostle, Saint Kuriakose, and Saint Mary in the southern portion of the Chera Empire's capital city of Cranganore. According to tradition the three churches were built by Thomas of Cana when the community arrived to India.[51] Zacharias was the 14-year-old deacon of St. Kuriakose Church as well as the scribe and pupil of Mar Yaqob of India, a 14th-century East Syriac bishop of Cranganore. Zacharias is the author of the oldest surviving Syriac manuscript of India archived as Vatican Syrian Codex 22 which details the city of Cranganore, relations between the Church of the East and the St. Thomas Christians, the Patriarch Yahballaha III, and Mar Yaqob of Cranganore whom he describes in the following quote:[52]

"This holy book was written in the royal, renowned and famous city of Chingala (Cranganore) in Malabar in the time of the great captain and director of the holy catholic church of the East.. our blessed and holy Father Mar Yahd Alaha V and in the time of bishop Mar Jacob, Metropolitan and director of the holy see of the Apostle Mar Thoma, that is to say, our great captain and the director of the entire holy church of Christian India"[53]

In the year 1456 the Knanaya Community approached the Kingdom of Vadakkumkoor to rebuild Kaduthuruthy St. Mary's Valiya Palli (Great Church). In audience with the King of Vadakkumkoor, the Knanaya presented him ponpannam (gold/gifts given to monarchs). After receiving permission to reconstruct the church, masons were called who during this time extended the walls of Kaduthuruthy Church and added a gopuram (entrance tower). The historical Knanaya folk song "Alappan Adiyil" written on palm-leaf manuscript records the reconstruction of Kaduthuruthy Church and includes the colophon date 1456. [54]

Early Portuguese Era

The first known extensive written evidence for a division in the Saint Thomas Christian community dates to the 16th century, when Portuguese colonial officials took notice of it.[55][56] A 1518 letter by the Jesuit missionary Alvaro Penteado mentions a conflict between the children of Thomas of Cana, hinting at a rift in the community in contemporary times.[55] In 1525, Mar Jacob, a Chaldean bishop in India, recorded a battle the year before between the Kingdom of Cochin and the Zamorin of Calicut that destroyed Cranganore and many Knanaya homes and churches.[57][58] The destruction of their entire township and the burning of their churches caused the Knanaya to disperse from the city to other settlements. The event is also noted in the Knanaya folk song "Innu Nee Njangale Kaivitto Marane" or "Have You Forgotten Us Today Oh Lord?".[58][59]

After the battle, a portion of the community migrated to the interior of Kerala to the foothills of the Western Ghats and founded the settlement of Chunkom which was developed into a customs house, where they eventually built St. Mary's Knanaya Church in 1579.[60]The Knanaya of Chunkom grew prosperous and carried out commerce in the region in which they regularly traded with the Kingdom of Travancore and the Tamil Dynasty of Madurai.[60] The local Brahmin chieftains grew indebted to the Knanaya and would offer slaves of the Malleen (Hill Arrian) caste to the community in order to settle their debts.[60] The Knanaya converted the Malleens to Christianity and built them a separate church known as St. Augustines. Besides collecting duties, the Knanaya in Chunkom were also known to mold "famous pottery".[60]

In the year 1550, the Portuguese commander Francesco Silveira de Menesis aided the King of Cochin's army in a victorious battle against the Kingdom of Vadakkumkur (Kaduthuruthy), subsequently killing its king Veera Manikatachen.[60][61][62] After the death of their king, the entire army of the Kingdom of Vadakkumkur formed itself into chaver (suicide) squads and sought revenge against the Syrian Christians in the region who they viewed as co-religionist of the regicidal Portuguese. The Knanaya Tharakan (minister) Kunchacko of the Kunnassery Family was a member of the Vadakkumkoor Royal Court and a close advisor to the slain king. In order to save his people from the ire of the chaver squads, Kunchacko Tharakan gathered the Knanaya from their parish of Kaduthuruthy St. Mary's Valiya Palli (Great Church), as well as all other Syrian Christians he could find within the vicinity of Vadakkankur and fled to the region of Mulanthuruthy where he eventually built Mulanthuruthy Church. The Knanaya were later called back to Kaduthurthy by the descendants of Veera Manikatachan and left Mulanthuruthy Church in the care and protection of the Northist St. Thomas Christians who remained there.[61][60]

During this same altercation with the Kingdom of Vadakkumkoor in 1550, a portion of the Knanaya from Kaduthuruthy were invited to the city of Kottayam by its chieftain in the Kingdom of Thekkumkur. The community was granted permission to build a church which they consecrated as Kottayam St. Mary's Knanaya Valiya Palli.[25][63] These Knanaya had brought with them ancient relics from Kaduthuruthy Church known as the Persian Crosses which are till this day exhibited at Kottayam Valiya Palli.[25] The crosses are inscribed in the Syriac and Pahlavi languages and are dated between the 8th and 10th century.[64] Translations of the crosses were made by the archeological director of India Arthur Coke Burnell in 1876 and Assyriologist C.P.T Winkworth in 1928. Winkworth produced the following citation presented at the International Congress of Orientalist (Oxford):

"My Lord Christ, have mercy upong Afras son of Chahar-bukht, the Syrian who cut this"[64]

In 1566 Portuguese official Damio De Goes records that the Thomas of Cana copper plate grant was given to the Portuguese treasurer Pero De Sequeia by the Chaldean Bishop of Cranganore Mar Jacob in 1524 after the destruction of the city in order to keep the plates safe.[65] Treasurer Pero De Sequeia then took the plates to the Portuguese governor of India Martim Afonso De Sousa who ordered the local people to translate the context of the plates.[65] To the governors dismay none of the local people could interpret the antiquity of the language on the plates, however the Portuguese eventually came into contact with a Cochin Jewish linguist who De Goes expresses was "versed in many languages".[65]Governor De Sousa sent the plates to the Jewish linguist with orders from the King of Cochin to interpret and translate its context.[65]

The linguist translated the context of the plates and stated that they contained social, economic, and religious rights given to Thomas of Cana by a local ruler and were written in three languages, namely "Chaldean, Malabar, and Arabic".[65]De Goes notes that physically the plates were "of fine metal each one palm and a half long and four fingers broad, written on both sides, and strung together at the top with a thick copper wire".[65]The Cochin Jew returned the plates to the Portuguese, who then had his Malayalam description of the plates translated to the Portuguese language in a written copy.[65] This copy was later sent by treasurer Pero De Sequeia to Portuguese King Dom Joao III. After this point, the physical plates were kept by Pero De Sequeia and his successor treasures at the Portuguese depot in Cochin.[65]

In 1579 the Jesuit missionary Monserrate wrote on the tradition of Thomas of Cana's two wives for the first time; he describes the division of the community, but gives no details about either side.[66][67]

In 1602 Portuguese priest Fr. Antonio De Gouvea notes that the Thomas of Cana copper plate grant which had been kept safe at the Portuguese factory of Cochin was by this point lost due to the "carelessness" of the Portuguese themselves.[68] De Gouvea states that the loss of the plates had greatly angered the Knanaya who had no other written record of their history and rights to defend themselves from local kings who by this point were infringing on their position.[68]

A 1603 letter by Portuguese official J. M. Campori further discusses the division of the community, which had by that point become intermittently violent; he states that the majority of Christians in Malabar are those baptized by St. Thomas the Apostle while a minority descend from Thomas of Cana.[69][25][70]

In 1603-1604 Portuguese Archbishop Francis Ros notes the tradition that before the coming of Thomas of Cana and his party, there existed in Malabar the native St. Thomas Christians.[71] When describing the division of the Christians he states the following:

"So that, already long before the coming of Thomas Cananeo, there were St. Thomas Christians in this Malavar, who had come from Mailapur, the town of St. Thomas. And the chief families are four in number: Cotur, Catanal, Onamturte, Narimaten, which are known among all these Christians, who became multiplied and extended through the whole of this Malavar, also adding to themselves some of the gentios who would convert themselves. However, the descendants of Thomas Cananeo always remained above them without wishing to marry or to mix with these other Christians."[71]

Ros expresses that discord arose between the Knanaya and St. Thomas Christians to the point where it became necessary to build separate churches in the regions Carturte (Kaduthuruthy) and Cotete (Kottayam).[71] Ros notes that the descendants of Thomas of Cana are a minority that reside in the churches Udiamperoor, Kaduthuruthy, Kottayam, and Turigore (Chunkom).[71] During this same time period, Archbishop Ros translated the context of the Thomas of Cana copper plate grant from an existing olla copy (palm-leaf manuscript).[72] The physical manuscript of Ros' Portuguese translation is archived at the British Museum as title MS. Add. 9853.[72] In this same work Ros notes also that the plates were taken to Portugal by Franciscans who left only a Portuguese copy in India. [36]

In 1611, chronicler and official historian of Portuguese India Diogo de Couto mentions the tradition that a contingent of families had accompanied Thomas of Cana and notes that these Christians are "without doubt Armenians by caste; and their sons too the same, because they had brought their wives". Couto attests that the descendants of Thomas of Cana and his party are a minority that reside in the Southist churches of Diamper (Udayamperoor), Kaduthuruthy, and Kottayam.[73][25]

Other Portuguese authors who wrote of the Southist-Northist divide, generally referencing versions of the Thomas of Cana story, include Franciscan friar Paulo da Trinidade (1630–1636),[74] and Bishop Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani (1657).[25][75] Sebastiani notes that in demographics the Knanaya numbered no more than 5000 persons in the 17th century and out of the 85 parishes of the Malabar Christians are only found in Udiamperoor, Kottayam, Thodupuzha (Chunkom), and Kaduthuruthy.[75]

Later Portuguese Era

After the death of Mar Abraham in 1599 (the last East Syriac bishop of Kerala), the Portuguese began to aggressively impose their dominion over the church and community of the St. Thomas Christians. This was epitomized by the Synod of Diamper in 1599 which took place at Udiamperoor Knanaya Church. The synod led by the Portuguese Archbishop of Goa Aleixo de Menezes, brought forth many social and liturgical reforms which forcefully Latinized the East Syriac Rite followed by the St. Thomas Christians and formally brought all the Indian churches under the Archdiocese of Goa and the Roman Catholic Church.[76]

In the 17th century, tensions began to broil between the St. Thomas Christians and the Portuguese over their hegemony of the community. The native Archdeacon and ecclesial head of the community Archdeacon Thomas, was often at odds with the Portuguese prelates. [77] Tensions further grew with the arrival of the Syrian Bishop Mor Ahatallah in India in 1652 who claimed to have been ordained as the "Patriarch of the Whole of India and China" by the Syriac Orthodox Church. The St. Thomas Christians wholeheartedly welcomed Mor Ahatallah and Archdeacon Thomas had hoped that this new Syrian bishop could free the community from the yolk of the Portuguese hierarchy.[78] Knowing of his influence, the Portuguese had detained Mor Ahatallah at Cochin and arranged for a ship to take him to Goa. Archdeacon Thomas is then noted to have arrived at Cochin backed by the militia of the St. Thomas Christians and demanded the Syrian bishops release. The Portuguese officials responded to Thomas and his militia by stating that the ship carrying Ahatallah had already left to Goa. [79] After this, Mor Ahatallah was never heard from again in India which started to incite anti-Portuguese sentiment among the community. Rumors had spread that the Portuguese had drowned Mor Ahatallah in the harbor at Cochin, this rumor became the breaking point in the relationship between the St. Thomas Christians and the Portuguese.[80]

In mass rebellion against the Portuguese clergy and in particular Archbishop Francisco Garcia Mendes, the St. Thomas Christians met on 3 January 1653 at Our Lady of Mattenchery Church to convoke the Coonan Cross Oath. The oath expressed that the community would no longer obey Archbishop Garcia nor the Portuguese Jesuits but instead only recognize their native archdeacon as the governor of their church. [80] After the oath, scholar Stephen Neill notes that the Knanaya priest Anjilimoottil Itty Thommen Kathanar of Kallissery played a major role in the eventual schism of the St. Thomas Christians from the Roman Catholic Church. Being a skilled Syriac writer, it is believed that Itty Thommen forged two letters supposedly from Mor Ahatallah one of which stated that in the absence of a bishop, twelve priests could lay hands on Archdeacon Thomas and consecrate him as their new patriarch, an old oriental Christian tradition. The two forged letters were read to mass crowds during church services and were received with much praise from the community. One of the letters was laid on the head of Archdeacon Thomas and twelve priests consecrated him as the first native bishop of Kerala. News of the event was spread throughout the churches of the St. Thomas Christians who accepted it with much joy in the fact that for the first time in their history a native bishop was consecrated.[81]

During these events, nearly the entire Knanaya community had remained faithful to Archbishop Garcia, questioning the validity of Archdeacon Thomas' ordination as non-canonical, with only Itty Thommen and his parishioners at Kallissery Knanaya Church supporting the archdeacon. [82][83] Other priests of the Knanaya became aware of Itty Thommens actions and called them into question.[82] In October 1653, the Knanaya convened a meeting at Kottayam in-which it was decided that none of them should accept Archdeacon Thomas as their bishop, nor should any of their people meet with him. The community even resolved that a young Knanaya who had been given minor orders from Archdeacon Thomas should not be recognized as a priest. Out of the five churches of the Knanaya, Kaduthuruthy, Chunkom, Kottayam, and Udiamperoor remained staunchly faithful to Archbishop Garcia, while only Kallissery Church led by Anjilimoottil Itty Thommen remained in rebellion.[83] Northist St. Thomas Christians also almost entirely defected from Archdeacon Thomas and instead supported Thomas' cousin and rival Parambil Chandy. Portuguese Archbishop and successor of Fransico Garcia, Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani noted that the Knanaya greatly supported Parambil Chandy even though he was a Northist St. Thomas Christian. In early 1663, the Knanaya tax-collector Pachikara Tharakan of Chunkom had met with Bishop Sebastiani and pledged the support of the Knanaya community to Parambil Chandy, stating that they would always remain obedient to him "even if all others abandoned him". In response, Parambil Chandy expressed that he would protect and preserve the Knanaya with his life, even more than his own community the Northist[84] Parambil Chandy would be ordained as the Catholic bishop of the St. Thomas Christians in 1663 at Kaduthuruthy Knanaya Church.[85]

The St. Thomas Christians would now be forever internally divide into Catholic and Malankara factions with the majority of the community who sided with Parambil Chandy creating the basis for the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church (Eastern Catholic), while the minority who remained with Archdeaon Thomas creating the Malankara Church (Oriental Orthodox)[86]

Later Colonial Era

In the early 18th century (1720) the Syrian Jacobite Catanar from Kaduthuruthy Fr. Mathew Veticutel wrote a short history of the Malabar Church in Syriac, which is archived today as MS 1213 at Leyden Academy Library. In contrast to the previously documented notations from European sources in the 16th and 17th centuries, Fr. Mathew's work is the first published native account of the historical traditions of the various ancient Christian missions to India such as that of St. Thomas the Apostle, Thomas of Cana, and bishops Mar Sabor and Mar Proth. Fr. Veticutel expresses that the native St. Thomas Christians had long been without priests and presbyters.[87] The Catholicos of the East had sent Thomas of Cana to investigate the condition of the Church in India. When Thomas returned and reported on the St. Thomas Christians, the Catholicos ordered Thomas, Uraha Mar Yoseph (Metropolitan of Edessa), presbyters and deacons, as well as men and woman from Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Nineveh to embark to India.[88] When the migrants arrived in the year 345, they were met by the Native St. Thomas Christians and later approached the King of Malabar from whom they received land and privileges in the form of copper plates. A town and church was then constructed in Cranganore upon which 472 houses were built in which the migrants and native St. Thomas Christians inhabited two distinct sides.[89]

In the late 18th century the Syrian Catholics could no longer tolerate the numerous abuses of power by the Roman Catholic Church towards the St. Thomas Christians which included the suppression of the Syriac Rite and the torturing of native clergy.[90] The tension between the Native Clergy and Roman Church met a breaking point when the Latin hierarchy had imprisoned and starved to death Northist Cathanar (Syriac priest) Chacko of Edappalli in 1774, who was wrongfully accused of stealing a monstrance.[91] After this the Malabar General Church Assembly had joined together in the venture of sending a delegation to Rome in order to meet the pope and have their grievances addressed as well as petition for the ordination of a native Syrian Catholic hierarch. The Northist cathanars Ousep Cariattil and Thomman Paremmakkal were tasked with undertaking the journey.[91] The journey was also greatly supported and funded by two Syrian Catholic Tharakans (ministers/tax collectors), Poothathil Itti Kuruvilla of the Knanaya Community and Thachil Mathoo of the Northist St. Thomas Christians.[92] Poothathil Itti Kuruvilla Tharakan had donated 30,000 chakrams (Indian currency) to the delegation, whose journey to Rome began in his home in the village of Neendoor. From Neendoor the delegation took Poothathil's country boat all the way to Colachel on the southern tip of India, after which point they left India.[93] The delegation also took one boy of each ethnic group to be admitted to the Propaganda College of Rome, Chacko Malayil of the Knanaya community and Mathoo Palakkal of the Northist.[94]

Modern era

In the late 19th century social changes in British India led to increased wealth and social power for the Saint Thomas Christians. This social change tended to advance internal divisions within the community, including the Southist–Northist division.[95] Through this period the Knanaya promoted their own uniqueness and independent identity to push for further opportunities for their community. They sought the establishment of Knanaya-centred diocese' for both the Malankara and Catholic churches, which were founded in 1910 and 1911, respectively.[95]

Like other Saint Thomas Christians, many Knanaya have migrated away from Kerala and India since the 20th century. The largest Knanaya diaspora community is located in Chicago.[96] This community originated in the 1950s when a small number of Knanaya and other Kerala natives emigrated to the area as university students; they were followed by more substantial immigration after 1965. The immigrants met up periodically for social events, and in the 1970s organizations for Catholics, members of other Christian churches, and Hindus were formed. In the 1980s the various Indian Catholic particular churches sent chaplains to Chicago; in 1983 the Bishop of Kottayam sent a chaplain to minister specifically to the Knanaya Catholics.[97]

Religion

The Syrian Christians of Kerala were historically organized as a province under the Church of the East following the East Syriac liturgical tradition. Following the Coonan Cross Oath of the 17th century, both the Knanaya and Northist groups were internally divided into Catholic and Malankara Church factions.[98] The Malankara faction became affiliated with the Syriac Orthodox Church, an Oriental Orthodox church based in Syria following the West Syriac liturgical tradition. The Catholic faction continued following the East Syriac liturgical tradition and would be elevated to the status of Sui Juris in 1887 by the Catholic Church. The now autonomous Eastern Catholic Church would become known as the Syro Malabar Catholic Church. Beginning in the late 19th century, both Malankara and Catholic Knanaya lobbied for their own dioceses within their respective denominations. In 1910, the Syriac Orthodox Church established a distinct Knanaya-oriented diocese in Chingavanam, which reports directly to the Patriarch of Antioch. The following year, the Catholic Church established a Knanaya Catholic eparchy (diocese) in Kottayam, known as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Archeparchy of Kottayam.[99]

Culture

The culture of the Knanaya community is an admixture of Syriac Christian, Jewish, and Hindu tradition.[100] Several comparative studies by Jewish scholars have noted that the Knanaya maintain distinct customs strikingly similar to those of the Cochin Jews of Kerala.[33][40][41] These cultural correlations are mainly exhibited in folk songs and folk traditions which may reflect the Knanaya's claimed Judeo-Christian ancestry. Jewish scholars note also that this may suggest "historic cultural relations between the two communities".[42][40] Scholar of Cochin Jewish culture and history P.M. Jussay notes the following about the cultural similarities:

"In the many splendoured wonder of Kerala's population, the critical observer is intrigued by the striking similarities that exist between two small communities - the Cochin Jews and the Knanite Christians. Neither of them is said to be of the soil; but having taken root and flourished for long in this fertile land, they have been indistinguishably integrated with its colours and contours. The similarities become significant when the Knanites claim a Jewish origin"[101]

Folk songs

| "Knanaya Folk Songs" | |

|---|---|

Palm Leaf Manuscripts of Knanaya Folk Songs | |

| Song | |

| Genre | Cultural Music |

| Length | 48:39 |

| Music video | |

| "Knanaya Folk Songs" on YouTube | |

Knanaya folk songs are considered ancient in origins and were first written down in the 17th century on palm leaf manuscripts recorded by Knanaya families. The texts of the palm leaves were compiled and published in 1910 by the Knanaya scholar P.U. Luke with the aide of Knanaya Catholic priest Fr. Mathew Vattakalm in the text Ancient Songs of the Syrian Christians of Malabar.[102][54][103][104][105] The songs were written in Old Malayalam but contain diction and lexemes from Sanskrit, Syriac, and Tamil.[106] Analytically, these ancient songs contain folklore about the faith, customs and practices of the community, narratives of historical events (such as the mission of St. Thomas the Apostle and the immigration of the Knanaya to India), biblical stories, songs of churches, and the lives of saints.[102] Scholars have also found that the songs of the Knanaya are of a similar composure, linguistics, and characteristic to that of the Cochin Jews and that some songs even have almost the same lyrics with the exception of a few words or stanzas. According to the Cochin Jewish scholar P. M. Jussay, "these similarities are not accidental and cannot be easily explained".[40][107]

Knanaya "Kuli Pattu" or Bath Song:

"Ponnum methiyadimel melle melle avan natannu

(With golden sandals he slowly walked)

Velli methiyadimel melle melle aval natannu"

(With silver sandals she slowly walked)[108]

Cochin Jewish procession song:

"Ponnum methiyadimel melle natannan, Chiriyanandan,

(With golden sandals Chiriyanandan (Joseph Rabban) slowly walked)

Velli methiyadimel melle natannan, Chiriyanandan"

(With silver sandals Chiriyanandan (Joseph Rabban) slowly walked)[108]

Some songs show the influence of the Hindu culture of Kerala. For instance, the Knanaya song Mailanjipattu is adapted from the Hindu song Krishnagatha.[109]

Songs of Hindu Bards

Historically a class of bards known as Panans would visit the homes of nobles castes in Kerala and sing songs of heroic figures as well as legendary events. After doing so the Panan would receive payment for their performance in the form of a material donation of items such as betel leaves and other types of charitable aid. Likewise, the Panans would visit the homes of the Knanaya and sing songs of the communities history and heritage. In particular, the Panans would sing of a story in the life of Thomas of Cana during the reign of Cheraman Perumal. The story is narrated from the perspective of the leader of the bards known as Tiruvaranka Panan. The contents of the story revolves around a mission bestowed to Tiruvaranka by Thomas of Cana in which he is to travel to Ezhathunadu (Sri Lanka) and implore four castes, namely carpenters, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, and molders, to return to Cranganore which they had left due to an infringement on their social traditions. The four castes are initially hesitant to return to Cranganore but are persuaded by Tiruvaranka when he shows them the golden staff of Thomas of Cana which he was granted to take on his journey as a sign of goodwill. After seeing the staff the four castes are content and in their satisfaction remove their own ornaments and smelt a golden crown for Thomas of Cana which they present to him upon their return to the Cranganore. Wearing the crown, Thomas and Tiruvarankan go to meet Cheraman Perumal who is pleased with the success of their mission and grants Thomas of Cana privileges. The remainder of the song sings of the seventy-two historical privileges bestowed upon Thomas.[110]

Folk traditions

After the burning of Craganore in 1524 during a battle between the Zamorin of Calicut and the Kingdom of Cochin which the city was a part of, the homes and temples of both the Cochin Jews and Knanaya were destroyed. The Knanaya historically commemorated this loss by carrying around a handful of charred earth as a keepsake from their ancestral settlement. From this act originated the custom of including a pinch of ash from a bride's home in a knot at the end of her new dress when she went to live with her husband. On account of this, Northists sometimes derisively dub the Knanaya "Charam kettikal", or knot makers of ash. The Cochin Jews had a similar custom of keeping a handful of earth from the place their temples once stood.[58] The burning of Craganore was a vital and drastic event for both the communities and figures heavily in their stories and songs[59]

Both the Knanaya and Cochin Jews maintain folk traditions based on figures and stories of the Old Testament. Both groups particularly revere Joseph; the Knanaya perform a circle dance called "Poorva Yousepintae Vattakali" ("Round Dance of Old Joseph"), while the Cochin Jews also maintain songs glorifying Joseph.[111] The Knanaya and Cochin Jews give local flavor to their Old Testament-based songs, stories and traditions. A Knanaya folk song about Tobias describes his wedding as including Kerala paraphernalia, while a Cochin Jewish folk song describes Ruth dressed and groomed like a Malayali girl or Cochin Jewish bride. For both the Knanaya and Cochin Jews, these flourishes make Bible stories relevant to their current experience.[112]

Passover traditions

The tradition of Passover or Pesaha is practiced every Holy Thursday in the homes of the Knanaya. On the night of Holy Thursday, the Pesaha Appam or Pesaha bread is made with unleavened flour along with a sweet drink made of milk and jaggery known as Pesaha Pal (in some families banana is also a part of this custom). The first batch of Pesaha appam is decorated and blessed with palm leaves from Palm Sunday set in the shape of a cross, the Pesaha milk also shares this adornment. The first batch is said to be the most sacred and is only given to members of the family. In ritualistic practice, the family gathers in the home and the father or grandfather of the household blesses and prays over the bread and milk, often also reading a bible passage. He then cuts, portions and distributes the bread, banana, and milk to his family members, giving it to males of the household first. Traditionally after the celebration is over any waste product that was used in the ritual was burned away according to the rules of Leviticus and the sacred nature of the practice. It should also be noted that all utensils and vessels used in the process are either brand new or washed in a ceremonial manner. Pesaha is also regularly practiced in the homes of the larger St. Thomas Christian community but the scope of usage can vary based on the specific denomination and region. Distinctions also occur based on the type of bread and products used and specific rituals that take place. Additionally, if a family is in mourning following a death, Pesaha bread is not made at their home, but brought to them by their Syrian Christian neighbors.[113][33]

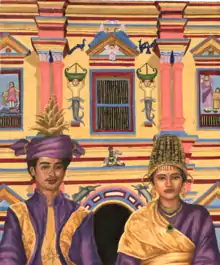

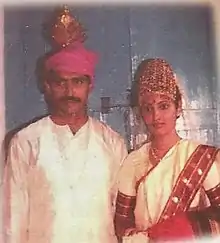

Wedding traditions

The Knanaya maintain distinctive wedding traditions and wedding customs that have helped to sustain their identity and culture. These traditions are an amalgamate of Judeo-Christian, Syriac, and Hindu customs, reflecting the Knanaya's claimed origins and the centuries that they have lived as a minority community in India. Historically, Knanaya marriage celebrations lasted several days, with many of the ceremonies centered around the home. In the present day, these ceremonies take place over three days and the wedding traditions can be divided into the categories of betrothal, groom, bride, reception, and miscellaneous. These ceremonies are also accompanied by numerous ancient songs characteristic of the Knanaya.[114]

Betrothal customs include Kaipidutham, or "clasping of hands". This is an initial agreement and fixing of the marriage, which involves the future bride and groom as well as their paternal uncles. The uncles clasp the hands of the betrothed in the presence of the priest at church. This symbolizes the uncles' and extended families', support and investment in the relationship.[115] Maternal uncles undertake a Maternal Uncles Agreement, at which they come together at the erection of the poles of the pandal, a canopy and temporary hall set up for the wedding. The uncles from each party exchange a kindy, or water bowl, for rinsing and hand washing. The dowry is also delivered by the bride's maternal uncle to the groom's uncle, and they kneel on a mat in front of a lighted lamp symbolizing Jesus and pray as though in front of an altar.[115]

Bride and groom participate in ceremonies in their respective homes on the eve of the wedding. The groom's ceremony is "Antham Charthal" which is now most commonly known as Chandam Charthal. The name signifies the end or last day of the bachelor life of the boy as well as beautifying the boy. The village barber arrives at the pandal and requests permission to shave the groom three times. After receiving permission, the barber performs the ceremonial shaving (historically, this was his first shave), then takes him out to put oil on his head and bathe him, while the assembly sings ancient songs.[116] The bride's ceremony is Mylanchi Ideel, or "henna ceremony". The bride's palms, feet, and nails are smeared with special green henna, by her paternal aunts. Similar ceremonies are found among various ethnic groups across the Middle East, North Africa, and India; the Knanaya give it a Biblical meaning referencing the original sin of Eve, stating that because Eve walked with her feet to the Tree of Knowledge and plucked its forbidden fruit with her palms, the feet and palms of the bride are smeared with henna to cleanse her of Eves original sin. The aunts then takes the bride to be bathed and changed into a new dress.[117] Following these ceremonies the bride and groom return to the pandal for the Ichappad (sweet giving) ceremony, at which the bride and groom are fed white rice pudding with brown sugar by paternal relatives (starting with uncles, male cousins and brothers).[118]

| "Bar Mariam" | |

|---|---|

Knanaya priests chant the "Bar Mariam" | |

| Song | |

| Genre | Paraliturgical |

| Length | 4:00-6:00 |

| Music video | |

| "Bar Mariam" on YouTube | |

Prior to entering the church for the wedding, the bride and groom greet their parents and elders for Sthuthi ("Peace Blessing"), where they receive blessings from their family. This is believed to be a reference to Sarah receiving her father's blessings in the Book of Genesis.[119] At the end of the marriage ceremony, the priests and congregation sing the "Bar Mariam" ("Son of Mary"), a "paraliturgical" Syriac chant referencing events from Jesus' life. After the chant, the priests bless the newlyweds with holy water to conclude the ceremony.[119][120]

The wedding reception features several traditions. After the wedding, the assembly holds a great procession to the reception place, including celebratory music and a distinct ritualistic cheer known as "Nada Villi". In the end, the bride and groom are carried by their uncles up to the door.[114] In the reception pandal, the groom's mother leads the Nellum Neerum ("Welcome Blessing") to solemnly welcome the newlyweds. The groom's sister holds a lighted brass lamp and a bowl of water, paddy, and leaves from Palm Sunday, symbolizing purification and fertility. The mother traces the sign of the cross on the couples' foreheads with a wet piece of palm leaf.[121] Special seats called manarcolam (marriage venue) are prepared for the couple by spreading sheets of wool and white linen, representing the hardships and blessings of married life.[114] The bride's mother then gives the Vazhu Pidutham (Mother's blessing) while placing her hands crosswise on the couple's heads, and all the women present sing the wedding song "Vazhvenna Vazvhu".[121] Following the mother's blessing, relatives present gifts in Kacha Thazhukal ("Gift Giving"). The first gift is a new dress given to the bride's family; family members then remove their gold jewelry and place them on the newlyweds.[121] Afterward is the presentation of milk and fruit, which the couple drinks from the same cup.[121]

After the reception is the Adachu Thura (Bridal Chamber Ceremony), where the bride's mother brings the groom special sweets and foods. The couple and their elders and friends enter the bridal chamber, where the bride's mother promises utensils and ornaments to the groom. They then exit the chamber and the bride and groom are anointed with oil and bathed. They put on new clothes and share a meal with the attendees. Special songs accompany each step. After that the bridegroom's family gifts the bride's family vazhipokala inorder to enjoy their return journey back home.[122] Another miscellaneous tradition is the Margam Kali ("The Way", referring to the way of Thomas the Apostle), a traditional St. Thomas Christian dance. The dance and accompanying songs retell the story of Thomas and his mission to India. [123]

Food

The Knanaya make several special foods. Pidy is a rice ball dish traditionally made when sending pregnant women home for a delivery, and some other occasions. Venpachor is a white rice pudding prepared on the eve of a wedding for the ceremonies of Chandam Charthal and Mylanchi Ideel. Other bread-based foods and snacks favored by the Knanaya but consumed by the entire Kerala community are Achappam, Kuzhalappam, Avalosunda, and Churutt.[124]

Knanaya historically ate on two plantain leaves, one placed over the other. According to folk tradition, this was a royal privilege granted to the community. Today, the Knanaya symbolize this by folding the left side of a plantain leaf underneath to make one leaf as two.[125] Knanaya eating together would eat from the same plantain leaf as a sign of cordiality. Catholic and Orthodox Knanaya dining together would eat from the left and right side of the leaf to show that despite their different religious affiliations, they were still part of a united ethnic community.[126]

Dress and ornaments

Knanaya women historically wore gold earrings with balls and small raised heads, one inch in diameter, known as Mekkamothiram or Kunukku, the same earrings are also worn by the Northist Saint Thomas Christians. Southist and Northist women alike wear a distinct type of sari known as the Chatta Mundu. This comprises the chatta, a white blouse embroidered with design, and the mundu dress. The mundu is a long white cloth worn from the waist down, and includes 15 to 21 pleats covering the back thigh in a fan shape representing a palm leaf.[123]

Knanaya men historically wore white shawls as a headdress and wore a white cloth wrapped around the waist. Both are tied in a special way known as Njettum Valum Ittu Kettuka.[123]

Dance

The Knanaya maintain a distinct round dance, the Margamkali, or "the way/path" of Thomas the Apostle. The Margamkali was traditionally a male dance exhibiting twelve players symbolizing the Twelve Apostles dancing in a circle around a lighted brass lamp representing Jesus. It is accompanied by ancient songs about Thomas the Apostle, based on the apocryphal 3rd-century text Acts of Thomas. The song text consists of 450 lines, divided into 14 sections. These songs contain Syriac and Tamil diction, suggesting an origin before the emergence of the Malayalam language in Malabar between the 9th and 13th century.[103]

In the 17th century, the Knanaya priest Anjilimoottil Itty Thommen Kathanar revised the text, which has influenced its current structure. In 1910, scholar P.U. Luke published the text for the first time in his collection of Ancient Songs.[103] In 1924 the European priest and scholar Father Hosten was enamored by the Margamkali he saw danced by the Knanaya in Kottayam. He attempted to present the dance at the 1925 Vatican Mission Exhibition, but it was not performed due to mass disapproval by Northist Saint Thomas Christians.[127] In the 1960s the Saint Thomas Christian scholar of folk culture Chummar Choondal led a sociological survey of the Margamkali. He noted that by that time, it was solely practiced and propagated by the Knanaya and could not be found among Northist communities.[127] Furthermore, Choondal found that all of the Margam teachers and groups of the time period were Knanaya.[127] With Choondal's aid, the Knanaya priests George Karukaparambil and Jacob Vellian spearheaded research on the Margamkali in the 1970s and '80s with the help of 33 Knanaya ashans (teachers). The team systematized the Margamkali and promoted it among schools and cultural organizations. In 1995, Mar Kuriakose Kunnasserry, the bishop of the Knanaya Diocese of Kottayam, established Hadusa (Syriac for dancing/rejoicing) as an All India Institute of Christian Performing Arts.[25]

Funeral traditions

The Knanaya hold to a death bed tradition based on Old Testament teachings, wherein a dying man gives a final blessing to his children and grandchildren. The father places his hand on the heads of kneeling recipients while giving the invocation.[123] Other funeral traditions include the Thazhukuka, in which friends and relatives embrace a grieving family at a funeral. The family stands in line at the church as the priest sprinkles holy water on them, and friends embrace them. After the burial, the family holds a ceremony at home where they drink from a single tender coconut to symbolize their unity following the death of their loved one.[124]

Institutions

Though a minority community, the Knanaya have established several institutions throughout the state of Kerala such as schools, colleges, and hospitals listed in the following figures: [128]

- Colleges - 4

- Higher Secondary Schools - 10

- High Schools - 20

- Upper Primary Schools - 18

- Lower Primary Schools - 55

- Nursery Schools - 80

- School of Nursing - 2

- College of Pharmacy - 1

- Multi-Health Workers School - 1

- Industrial Trade Schools - 1

- Poly-technical schools - 1

- Industrial Schools - 39

- Hospitals - 6

- Homes for the Aged - 6

- Homes for the Mentally Retarded - 7

- Homes for the Disabled - 4

- Hostels - 18

- Orphanages - 6

- Publishers - 2

References

- Fahlbusch 2008, p. 286.

- Swiderski 1988b, pp. 55–56.

- Kollaparambil 1992, p. 85.

- Kochadampallil 2019, pp. 33–34.

- Luke 1911, p. 72.

- Vellian 1986, p. 13-24.

- Kollaparambil 1992, p. 1.

- Neill 2004, p. 42.

- Kollaparambil 1992, pp. 1–20.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 73.

- Karukaparambil 2005, p. 470.

- Vellian 2001, p. 2.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 77.

- Malekandathil 2003, pp. 19–20.

- Kochadampallil 2019, pp. 34.

- Podipara 1971, p. 2.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 76–80.

- Coward 1993, p. 19.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 73–74.

- Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 53.

- Karukaparambil 2005, pp. 60.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 25–26.

- Neill 2004, pp. 42–43.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 74–76.

- Karukaparambil 2005, p. 497.

- Thodathil 2001, pp. 111–112.

- Kochadampallil 2019, pp. 24–32.

- Frykenberg 2010, pp. 113.

- King 2018, pp. 663-679.

- Karukaparambil 2005, pp. 460–461.

- Swiderski 1988b, p. 52.

- Swiderski 1988b, pp. 63–64.

- Weil 1982, pp. 175–196.

- Narayanan 2018, pp. 302-303.

- Swiderski 1988b, pp. 65–66.

- Kollaparambil 2015, pp. 148–149.

- Swiderski 1988b, pp. 66–67.

- Vellian 1986, pp. 54–55.

- Kollaparambil 1992, p. 110-125.

- Jussay 2005, pp. 118–128.

- Gamliel 2009, pp. 90.

- Gamliel 2009, pp. 377.

- Swiderski 1988b, pp. 95–96.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 89.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 73–92.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 76–77.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 77–78.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 80–82.

- Vellian 1986, p. 36.

- Kollamparambil 2012, p. 48.

- Vellian 1986, p. 22.

- Hatch 2012, p. 226.

- Podipara 1979, p. 15.

- Luke 1911.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 83.

- Sharma & Sharma 2004, p. 12.

- Vellian 1986, p. 2-3.

- Jussay 2005, p. 30.

- Jussay 2005, p. 123.

- Whitehouse 1873, p. 125.

- Karukaparambil 2005, p. 150.

- Trivedi 2010, p. 70.

- Trivedi 2010, p. 71.

- Winkworth 1929, p. 237-244.

- Vellian 1986, p. 4-5.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 77, 83.

- Vellian 1986, p. 8.

- Vellian 1986, p. 11.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 83–84.

- Vellian 1986, p. 21-22.

- Vellian 1986, p. 18-19.

- Vellian 1986, p. 13.

- Vellian 1986, pp. ii, 22-25.

- Vellian 1986, pp. 25–27.

- Vellian 1986, pp. 32–33.

- Neill 2004, pp. 208–214.

- Frykenburg 2008, pp. 367.

- Neill 2004, pp. 316–317.

- Frykenburg 2008, pp. 367–378.

- Neill 2004, pp. 319.

- Neill 2004, pp. 320–321.

- Neill 2004, pp. 322.

- Vellian 1986, p. 29-31.

- Vellian 1986, p. 35-36.

- Neill 2004, pp. 325.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 86.

- Vellian 1986, p. 42.

- Vellian 1986, p. 43.

- Vellian 1986, p. 44.

- Podipara 1971, p. 15-18.

- Podipara 1971, p. 40-41.

- Podipara 1971, p. 41-75.

- Vellian 1990, p. 50.

- Podipara 1971, p. 65.

- Swiderski 1988a, p. 87.

- Swiderski 1988b, p. 169.

- Jacobsen & Raj 2008, pp. 202–207.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 84–85, 87.

- Swiderski 1988a, pp. 87–88.

- Thodathil 2001, pp. 46.

- Jussay 2005, pp. 118.

- Jussay 2005, p. 119.

- Vellian 1990, p. 31.

- Gamliel 2009, pp. 390.

- Vellian 2001, pp. 56.

- Gamliel 2009, pp. 80.

- Vellian 1990, p. 32.

- Jussay 2005, p. 121.

- Swiderski 1988c, pp. 128–133.

- Karukaparambil 2005, p. 427-436.

- Jussay 2005, p. 124.

- Jussay 2005, p. 125.

- Alumkalnal 2013, pp. 57–71.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 25–38.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 32–33.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 33–34.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 34–35.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 33–35.

- Vellian 1990, p. 35.

- Palackal and Simon 2015.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 36–37.

- Vellian 1990, p. 38.

- Vellian 1990, p. 30.

- Vellian 1990, p. 28.

- Vellian 1990, p. 29.

- Vellian 1990, pp. 28–29.

- Karukaparambil 2005, p. 582-583.

- Vellian 2001, p. 40-42.

Bibliography

- Alumkalnal, Sunish (2013). Pesaha Celebration of Nasranis: A Sociocultural analysis. Journal of Indo-Judaic studies. 13.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Coward, Harold (1993). Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Perspectives and Encounters. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-1158-4.

- Fahlbusch, Ernst (2008). The Encyclopedia of Christianity: Volume 5. Eerdmans. p. 286. ISBN 9780802824172.

- Frykenberg, Robert (2010). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199575831.

- Gamliel, Ophira (April 2009). Jewish Malayalam Women's Songs (PDF) (PhD). Hebrew University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Hatch, William (2012). An Album of Dated Syriac Manuscripts. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-4632-3315-0.

- Jacobsen, Knut A.; Raj, Selva J. (2008). South Asian Christian Diaspora: Invisible Diaspora in Europe and North America. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754662617. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Joseph, T.K. (1928). "Thomas Cana". The Indian Antiquary. The British Indian Press. 57.

- Jussay, P. M. (2005). The Jews of Kerala. Calicut: Publication division, University of Calicut.

- Karukaparambil, George (2005). Marganitha Kynanaitha: Knanaya Pearl. Deepika Book House. ASIN B076GCH274.

- King, Daniel (2018). The Syriac World. Routledge Press. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Kochadampallil, Mathew (2019). Southist Vicariate of Kottayam. Media House Delhi. ISBN 978-9387298668.

- Kollaparambil, Jacob (1992). The Babylonian origin of the Southists among the St. Thomas Christians. Pontifical Oriental Institute. ISBN 8872102898.

- Kollaparambil, Jacob (2012). Kottayam Athirupatha Sathabdhi Smaranika: Sabha Saktheekaranam Knanaya Presthithadauthyam. Catholic Mission Press Kottayam.

- Kollaparambil, Jacob (2015). Sources of the Syro Malabar Law. Oriental Institute of Religious Studies India. ISBN 9789382762287.

- Luke, P.U. (1911). Ancient Songs. Jyothi Book House.

- Narayanan, M.G.S (2018). Perumals of Kerala. Cosmo Books. ISBN 978-8193368329.

- Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54885-3. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Palackal, Joseph J.; Simon, Felix, eds. (2015). "Bar maryam (Son of Mary)". Encyclopedia of Syriac Chants. Christian Musicological Society of India.

- Malekandathil, Pius (2003). Jornada of D. Alexis Menezes: A Portuguese Account of the Sixteenth Century Malabar. LRC Publications. ISBN 81-88979-00-7.

- Podipara, Placid (1971). The Varthamanappusthakam. Pontifcal Oriental Institute. ISBN 978-81-2645-152-4.

- Podipara, Placid (1979). The Rise and Decline of the Indian Church of the Thomas Christians. Oriental Institute for Religious Studies. ASIN B0000EDU30.

- Sharma, Suresh K.; Sharma, Usha (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Christianity. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-959-1.

- Swiderski, Richard Michael (1988). "Northists and Southists: A Folklore of Kerala Christians". Asian Folklore Studies. Nanzan University. 47 (1): 73–92. doi:10.2307/1178253. JSTOR 1178253.

- Swiderski, Richard Michael (1988). Blood Weddings: The Knanaya Christians of Kerala. Madras: New Era. ISBN 9780836424546. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Swiderski, Richard Michael (1988). "Oral Text: A South Indian Instance" (PDF). Oral Tradition. 3 (1–2): 129–133. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Thodathil, James (2005). Antiquity and Identity of the Knanaya Community. Knanaya Clergy Association. ASIN B000M1CEDI.

- Trivedi, S.D. (2010). Glorious Heritage of India: Research Papers on History, Art, and Epigraphy. Agam Kala Prakashan. ISBN 9788173200953.

- Vellian, Jacob (1990). Crown, Veil, Cross: Marriage Rights. Syrian Church Series. 15. Anita Printers. OCLC 311292786.

- Vellian, Jacob (2001). Knanite Community: History and Culture. 17. Jyothi Book House. OCLC 50077436.

- Vellian, Jacob (1986). Symposium on Knanites. Syrian Church Series. 12. Jyothi Book House.

- Weil, Shalva (1982). "Symmetry between Christians and Jews in India: The Cananite Christians and Cochin Jews in Kerala". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 16 (2): 175–196. doi:10.1177/006996678201600202. S2CID 143053857.

- Whitehouse, Richard (1873). Lingerings of Light in a Dark Land: Being Researchs into the Past History and Present Condition of the Syrian Church of Malabar. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 116492317X.

- Winkworth, C.P.T (1929). "A New Interpretation of The Pahlavi Cross Inscriptions of Southern India". The Journal of Theological Studies. Oxford University Press. 30 (119): 237–255. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXX.April.237.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Knanaya people. |