Malankara Church

The Malankara Church refers to the collection of Indian apostolic churches, according to tradition, that claims ultimate origins from the missions of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century in India and were under the leadership of Marthoma I after the historical Coonan Cross Oath of 1653. All the Churches belonging to the Malankara patrimony follow the Antiochian West Syriac Rite liturgy. The word "Malankara" is a combination of two words, 'Mala' which means mountains and 'Kara' which means land surface; and refers to the state of Kerala in India.

| Malankara Church | |

|---|---|

| Type | Eastern Christian |

| Classification | Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Protestant Christianity, Oriental Catholic |

| Theology | Miaphysitism, Diophysitism, Reformed Oriental |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Metropolitan Bishop | Malankara Metropolitan |

| Region | Kerala, India |

| Language | Suriyani Malayalam, Classical Syriac, Malayalam |

| Liturgy | Antiochian Rite- Liturgy of Saint James |

| Headquarters | Pazhaya Seminary |

| Founder | Thomas the Apostle as per tradition. |

| Origin | 52 AD (1st century as per tradition) |

| Branched from | Saint Thomas Christians[lower-alpha 1] |

| Separations | Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church (1670, 1772, 1898, 1914)[4] Malabar Independent Syrian Church (1772) Mar Thoma Syrian Church (1898),(1961) Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (1914),(1930) Syro-Malankara Catholic Church (1930) |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity in India |

|---|

|

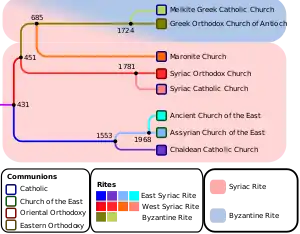

The modern-day descendants of the Malankara Church are the Oriental Orthodox Jacobite Syrian Christian Church (JSCC); the JSCC are an integral part of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. The autocephalous Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (MOSC), also known as the Indian Orthodox Church is part of the Oriental Orthodox communion. The Mar Thoma Church (MTC) is an independent Oriental Protestant church that split off in the 19th century, and since established communion with the Church of England and the Anglican communion. The Malankara Syrian Catholic Church is the faction that joined with the Holy See of Rome in 1930.[5][6]

This Malankara land had a historical trade connection with the Middle East nations from the ancient era and the traders from Egypt, Persia, and the Levant frequently visited this land for getting spices. These groups included Arabs, Jews and also Christians, and the Christians who visited here maintained contact with the Malankara Church. As such the Church in Malankara was in touch with other Eastern churches such as the Coptic and Persian churches. The Malankara Church was headed by the Archdeacon is known as Head of Malankara Christians. Archdeacon is the highest post for a cleric in the Church of the East after a bishop. Later a regular 'Bishopric' was established in Malankara with the help of Gregorios Abdal Jaleel Jerusalem Bishop of Syriac Orthodox Church, who oversees the faithful from the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch.[7][8][9]

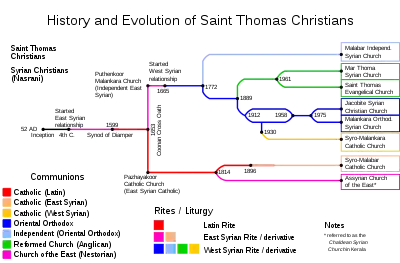

The Malankara Church was unique and unanimous till the 16th century and it was consolidated under the India-Eccesiastical Province of the Church of the East. Later some rifts happened due to the colonization of the Latin Catholic Portuguese padroado missionaries. After the Synod of Diamper, the Church was absorbed into the Archdiocese of Goa, administered by Latin Padroado. This led to gradual schism among the St. Thomas Christians. The Malankara Church , led by Archdeacon Thomas, who was regularised as a canonical bishop in 1665, by Archbishop Mor Gregorios Abdul Jaleel of the Syriac Orthodox Church, adopted the Oriental Orthodox faith and affiliated themselves to the Oriental Orthodox Communion. The other faction that was led by Palliveettil Mar Chandy, cousin of Marthoma I and consecrated as a Bishop in 1663, affiliated with the Propaganda Fide missionaries of the Catholic Church. They constitute the contemporary Eastern Catholic Syro-Malabar Church.[10] The faction of people who stood with the Archdeacon (Mor Thoma I) initially remained independent as Malankara Nasranis, also known as Tarisaykal which means "Orthodox". With the arrival of Mar Gregorios Abdal Jaleel Bawa in 1665 from the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, he was able to establish ties between the Malankara Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church. And adopt over the Malankara Rite liturgy from the West Syriac liturgy of the Syriac Orthodox Church instead of the Babylonian liturgy of the erstwhile Church of the East.[11]

Later a number of splits happened in Malankara Church due to the influence of foreign missionaries and internal conflicts. In the year 1772 a Syriac Orthodox bishop consecrated Kattumangatt Kurien (Mar Cyril) as his successor against the wishes of the Metropolitan, Mar Dionysius I; Cyril led a faction that eventually became the Malabar Independent Syrian Church.[12][13] In the 19th century, a reform movement inspired by British missionaries led to the formation of the independent Mar Thoma Syrian Church under the leadership of the incumbent Malankara Metropolitan, Mathews Mar Athanasius, while the rest of the church, resistant to British influence and affiliated to Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, came under the direct jurisdiction of the Pulikkootil Joseph Mar Divanasios, who was created Malankara Metropolitan by Ignatius Peter IV, the incumbent Jacobite Patriarch is known as Syriac Orthodox Church of India (Known as Jacobite Syrian Christian Church).[14][5] In 1911, the church was divided into two factions due to internal disputes. Since then the faction that supported the patriarch of antioch was known as Bava Kakshi (Patriarch faction) or the jacobite church and Methran Kakshi (bishop faction) or Malankara orthodox who supported Geevarghese Dionysius of Vattasseril Malankara Metropolitan[15] later Methran Faction(Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church) ordained Catholicos in 1912 by excommunicated Patriarch Ignatius Abded Mshiho II creating fear in the Malankara Church that he would attempt to take control of the church, reversing the decisions of the Council of Mulanthuruthy in 1876.[16] The Apex Court of India passed a remarkable judgement on the Malankara Church dispute on 3 July 2017 in favor of Malankara Metropolitan and Catholicose and this put an end to all the internal conflicts in the Malankara Church. The faction that supports the Patriarch of Antioch continue as Jacobite Syrian Christian Church (also known as the Syriac Orthodox Church of India), Later established Catholicate / Maphrianate of the East in India renamed to Catholicos of India.[17][18]

Terminology

Initially the terms "Malankara Christians" or "Malankara Nasranis" were applied to all Saint Thomas Christians,[19] but following the split the term was generally restricted to the faction loyal to Mar Thoma I the then Malankara Metropolitan, and distinguishing them from the Roman Catholic faction.[20] Later, many of the churches that subsequently branched off have maintained the word in their names. At the time of the split, the branch affiliated with Mar Thoma was called the Puttankuttukar, or "New Party", while the branch that entered into Catholic obedience was designated the Pazhayakuttukar, or "Old Party". The Portuguese Roman Catholics were not in familiar with the traditions of Eastern Christianity . In the view of Portuguese Missioneries the Nasranis who practice the Rituals of Eastern Christianity are new traditionals and there for they called the Malankara Nazranis Puttankuttukar, or "New Party" and they called themselves as Pazhayakuttukar, or "Old Party". Following the association with the Syriac Orthodox Church, the church was often known as the Malankara Syrian Church (Malayalam: മലങ്കര സുറിയാനി സഭ) in reference to their connection to the West Syriac tradition.

Early history of Christianity in India

As a Saint Thomas Christian group, the Malankara Church traced its origins to Thomas the Apostle, said to have proselytized in India in the 1st century.[5] Different strains of the tradition have him arriving either by sea[21] or by land. There is no direct contemporary evidence for Thomas coming to India, but such a trip would certainly have been possible for a Roman Jew to have made; communities such as the Cochin Jews and the Bene Israel are known to have existed in India around that time. The earliest text connecting Thomas to India is the Acts of Thomas, written in Edessa perhaps in the 2nd century. Some early Indian sources, such as the "Thomas Parvam" or "Song of Thomas", further expand on the tradition of the apostle's arrival and activities in India and beyond. Generally he is described as arriving in the neighbourhood of Maliankara and establishing Seven Churches, the Ezharapallikal: Cranganore (ml:കൊടുങ്ങല്ലൂര്), Paravur (Kottakavu) (ml:കോട്ടക്കാവ്), Paloor St. Mary's Orthodox Cathedral, Arthat (ml:പാലൂർ), Gokkamangalam (ml:ഗോക്കമംഗലം), Niranam (ml:നിരണം), Chayal (ml:ചായൽ) and Kollam (Quilon) (ml:കൊല്ലം).[22] Eusebius of Caesarea mentions that his mentor Pantaenus found a Christian community in India in the 2nd century, Church History of Eusebius. Book V, Chapter X.</ref> while references to Thomas' Indian mission appear in the works of 3rd and 4th century writers of the Roman Empire, including Ambrose of Milan, Gregory of Nazianzus, Jerome, and Ephrem the Syrian, showing that the Thomas tradition was well established across the Christian world by that time.[23][24]

Whatever the historicity of the Thomas tradition, the earliest organised Christian presence in India dates around the 3rd century, when East Syriac settlers and missionaries from Persia, members of what became the Church of the East or Nestorian Church, established themselves in Kerala.[25] The Thomas Christians trace the further growth of their community to the mission of Thomas of Cana, a Nestorian from the Middle East said to have relocated to Kerala some time between the 4th and 8th century.[23] The subgroup of the Saint Thomas Christians known as the Southists trace their lineage to the high-born Thomas of Cana, while the group known as the Northists claim descent from Thomas the Apostle's indigenous converts who intermarried with Thomas of Cana's children by his concubine or second wife.[23]

As the community grew and immigration by East Syriac Christians increased, the connection with the Church of the East, centred in the Persian capital of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, strengthened. From the early 4th century the Patriarch of the Church of the East provided India with clergy, holy texts, and ecclesiastical infrastructure, and around 650 Patriarch Ishoyahb III solidified the Church of the East's jurisdiction over the Saint Thomas Christian community.[26] In the 8th century Patriarch Timothy I organised the community as the Ecclesiastical Province of India, one of the church's illustrious Provinces of the Exterior. After this point the Province of India was headed by a metropolitan bishop, provided from Persia, the "Metropolitan-Bishop of the Seat of Saint Thomas and the Whole Christian Church of India".[23] His metropolitan see was probably in Cranganore, or (perhaps nominally) in Mylapore, where the shrine of Thomas was located.[23] Under him were a varying number of bishops, as well as a native Archdeacon, who had authority over the clergy and who wielded a great amount of secular power.[23]

Cheppeds: Collection of deeds on copper plates

The Rulers of Kerala, in appreciation for their assistance, gave to the Malankara Nazranis, three deeds on copper plates. They gave the Nasranis various rights and privileges which were written on copper plates. These are known as Cheppeds, Royal Grants, Sasanam etc.[27]

- Iravi Corttan Deed: In 1225 AD Sri Vira Raghava Chakravarti gave a deed to Iravi Corttan (Eravi Karthan) of Mahadevarpattanam in 774. Two Brahmin families are witness to this deed showing that Brahmins were in Kerala by the 8th century.

- Tharissa palli Deed I: Perumal Sthanu Ravi Gupta (844–885) gave a deed in 849 AD, to Isodatta Virai for Tharissa Palli (church) at Curakkeni Kollam. According to historians, this is the first deed in Kerala that gives the exact date.[28]

- Tharissa palli Deed II: Continuation of the above, given after 849 AD.

These plates detail privileges awarded to the community by the then rulers. These influenced the development of the social structure in Kerala and privileges, rules for the communities . These are considered as one of the most important legal documents in the history of Kerala.[29] Three of these are still in the Orthodox Theological Seminary (Old Seminary) in Kottayam and two are at the Mar Thoma Church Headquarters in Tiruvalla.[30]

Archdeacons

The position of archdeacon – the highest for clergy who are not a bishop – had great importance in the church of India in the centuries leading up to the formation of an independent Malankara Church. Though technically subordinate to the metropolitan, the archdeacon wielded great ecclesiastical and secular power, to the extent that he was considered the secular leader of the community and served as effective head of the Indian Church in times when the province was absent a bishop. Unlike the metropolitan, who was evidently always an East Syriac sent by the patriarch, the archdeacon was a native Saint Thomas Christian. In the documented period the position was evidently hereditary, belonging to the Pakalomattam family, who claimed a privileged connection to Thomas the Apostle.[23][31]

Details on the archidiaconate prior to the arrival of the Portuguese are elusive, but Patriarch Timothy I (780 – 823) called the Archdeacon of India the "head of the faithful in India", implying an elevated status by at least that time.[32] In the recorded period of its history, the office of archdeacon was substantially different in India than in the rest of the Church of the East or other Christian churches. In the broader Church of the East, each bishop was attended by an archdeacon, but in India, there was only ever one archdeacon, even when the province had multiple bishops serving it.[33]

Following the collapse of the Church of the East's hierarchy in most of Asia in the 14th century, India was effectively cut off from the church's heartland in Mesopotamia and formal contact was severed. By the late 15th century India had had no metropolitan for several generations, and the authority traditionally associated with him had been vested in the archdeacon.[34] In 1491 the archdeacon sent envoys to the Patriarch of the Church of the East, as well as to the Coptic Pope of Alexandria and to the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, requesting a new bishop for India. The Patriarch of the Church of the East Shemʿon IV Basidi responded by consecrating two bishops, Thoma and Yuhanon, and dispatching them to India.[34] These bishops helped rebuild the ecclesiastical infrastructure and reestablish fraternal ties with the patriarchate, but the years of separation had greatly affected the structure of the Indian church. Though receiving utmost respect, the metropolitan was treated as a guest in his own diocese; the Archdeacon was firmly established as the real power in the Malankara community.[35]

Arrival of the Portuguese

At the time the Portuguese arrived in India in 1498, the Saint Thomas Christians were in a difficult position. Though prosperous owing to their large stake in the spice trade and protected by a formidable militia, the tumultuous political climate of the time had placed the small community under pressure from the forces of the powerful rajas of Calicut, Cochin, and the various smaller kingdoms in the area. When the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama arrived on the South Indian coast, the leaders of the Saint Thomas community greeted them and proffered a formal alliance to their fellow Christians.[36] The Portuguese, who had keen interest in implanting themselves in the spice trade and in expanding the domain of their bellicose form of Christianity, jumped at this opportunity.[37]

The Portuguese brought to India a particularly militant brand of Christianity, the product of several centuries of struggle during the Reconquista, which they hoped to spread across the world.[38] Facilitating this objective was the Padroado Real, a series of treaties and decrees in which the Pope conferred upon the Portuguese government certain authority in ecclesiastical matters in the foreign territories they conquered.[39] Upon reaching India the Portuguese quickly ensconced themselves in Goa and established a church hierarchy; soon they set themselves to bringing the native Christians under their dominion. Towards this goal, the colonial establishment felt it necessary to conduct the Saint Thomas Christians fully into the Latin Rite, both in bringing them into conformity with Latin church customs and in subjecting them to the authority of the Archbishop of Goa.

Following the death of Metropolitan Mar Jacob in 1552, the Portuguese became more aggressive in their efforts to subjugate the Saint Thomas Christians.[40] Protests on the part of the natives were frustrated by events back in the Church of the East's Mesopotamian heartland, which left them devoid of consistent leadership. In 1552, the year of Jacob's death, a schism in the Church of the East resulted in there being two rival patriarchates, one of which entered into communion with the Catholic Church, and the other of which remained independent. At different times both patriarchs sent bishops to India, but the Portuguese were consistently able to outmaneuver the newcomers or else convert them to Latin Rite Catholicism outright.[41] In 1575 the Padroado declared that neither patriarch could appoint prelates to the community without Portuguese consent, thereby cutting the Thomas Christians off from their hierarchy.[42]

By 1599 the last Metropolitan, Abraham, had died, and the Archbishop of Goa, Aleixo de Menezes, had secured the submission of the young Archdeacon George, the highest remaining representative of the native church hierarchy.[43] That year Menezes convened the Synod of Diamper, which instituted a number of structural and liturgical reforms to the Indian church. At the synod, the parishes were brought directly under the Archbishop's authority, certain "superstitious" customs were anathematized, and the traditional variant of the East Syriac Rite, was purged of elements unacceptable by the Latin standards.[44] Though the Saint Thomas Christians were now formally part of the Catholic Church, the conduct of the Portuguese over the next decades fueled resentment in parts of the community, ultimately leading to open resistance.[20]

Coonan Cross and the independent church

Over the next several decades, tensions seethed between the Latin prelates and what remained of the native hierarchy. This came to a head in 1641 with the ascension of two new protagonists on either side of the contention: Francis Garcia, the new Archbishop of Kodungalloor, and Archdeacon Thomas, the nephew and successor to Archdeacon George.[45] In 1652, the escalating situation was further complicated by the arrival in India of a mysterious figure named Ahatallah.[45][46]

Ahatallah arrived in Mylapore in 1652, claiming to be the rightful Patriarch of Antioch who had been sent by the Catholic pope to serve as "Patriarch of the Whole of India and of China".[47] Ahatallah's true biography is obscure, but some details have been established. He appears to have been a Syriac Orthodox Bishop of Damascus who converted to Catholicism and went to Rome in 1632. He then returned to Syria in order to bring the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch Ignatius Hidayat Allah into communion with Rome. He had not accomplished this by the time Hidayat Allah died in 1639, after which point Ahatallah began claiming he was Hidayat Allah's rightful successor. In 1646 he was in Egypt at the court of the Coptic Pope Mark VI, who dispatched him to India in 1652, evidently in response to a request for aid from Archdeacon Thomas. Reckoning him an impostor, the Portuguese arrested him, but allowed him to meet with members of the Saint Thomas Christian clergy, whom he impressed greatly. The Portuguese put him on a ship bound for Cochin and Goa, and Archdeacon Thomas led his militia to Cochin demanding to meet with the Patriarch. The Portuguese refused, asserting that he was a dangerous invader and that the ship had already sailed on to Goa.[47]

Ahatallah was never heard from again in India, and rumours soon spread that Archbishop Garcia had disposed of him before he ever reached Goa.[48] Contemporary accounts allege that he was drowned in Cochin harbour, or even that the Portuguese burned him at the stake.[48][49] In reality, it appears that Ahatallah did in fact reach Goa, from whence he was sent on to Europe, but he evidently died in Paris before reaching Rome where his case was to be heard.[48] In any event, Garcia's dismissiveness towards the Saint Thomas Christians' appeals only embittered the community further.[48]

This was the last straw for the Saint Thomas Christians, and in 1653 Thomas and representatives of the community met at the Church of Our Lady in Mattancherry to take bold action. In a great ceremony before a crucifix and lighted candles, they swore a solemn oath that they would never obey Garcia or the Portuguese again, and that they accepted only the Archdeacon as their shepherd.[48] The Malankara Church and all its successor churches regard this declaration, known as the Coonan Cross Oath (Malayalam: കൂനൻ കുരിശു സത്യം).[48]

Later development

The oppressive rule of the Portuguese padroado provoked a violent reaction on the part of the indigenous Christian community. The first solemn protest took place in 1653, known as the Coonan Kurishu Satyam (Coonan Cross Oath). Under the leadership of Archdeacon Thoma, the St. Thomas Christians publicly took an oath in Mattancherry, Cochin, that they would not obey the Portuguese Catholic bishops and the Jesuit missionaries. Unfortunately there was no Metropolitan present in the Malankara Church at that time. Hence in the same year, at Alangad, Archdeacon Thoma was ordained, by the laying on of hands of twelve priests, as the first known indigenous Metropolitan of Kerala, under the name Mar Thoma I. The Portuguese missionaries attempted for reconciliation with Saint Thomas Christians but was not successful. Later Pope Alexander VII sent the Syrian bishop Joseph Sebastiani at the head of a Carmelite delegation who succeeded in convincing majority of Saint Thomas Christians, including Palliveettil Chandy Kathanar and Kadavil Chandy Kathanar. The Catholic faction constantly challenged the legitimacy of the consecration of Archdeacon as Metropolitan by priests. Palliveettil Mar Chandy Kathanar was consecrated as the bishop for the Syriac Catholics in 1663. This made it essential to rectify the illegitimacy of the consecration of Archdeacon as Metropolitan. Episcopal consecration of Mar Thoma I as a Bishop was regularized in the year 1665 by Mar Gregorios Abdal Jaleel Jerusalem Bishop of Syriac Orthodox Church. This led to the first permanent split in the Saint Thomas Christian community. Thereafter, the faction affiliated with the Catholic Church under Parambil Mar Chandy was designated the Pazhayakoottukar, or "Old Party", while the branch affiliated with Mar Thoma was called the Puthankoottukar, or "New Party". These appellations have been somewhat controversial, as both groups considered themselves the true heirs to the Saint Thomas tradition.

Mar Thoma I with 32 churches (out of 116 total churches) and their congregations were the body from which the Malankara Syrian Churches (Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, Mar Thoma Syrian Church, Syro-Malankara Catholic Church and Malabar Independent Syrian Church originated. In 1665, Mar Gregorios Abdul Jaleel, a Bishop sent by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch arrived in India and the Saint Thomas Christians under the leadership of the Archdeacon welcomed him.[50][51] The Gregorios Abdal Jaleel regularised the consecration of Archdeacon as Metropolitan of the Syriac Orthodox Church as per the apostolic standards of Kaiveppu (traditional legitimate way of laying hands by a valid Bishop). This resulted in reuniting the Malankara Church and the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch and the reaffirmation of the orthodox faith in the Church entrusted by the for-father's of the Syriac Orthodox Church, who are entombed in Malankara. The 18th century saw the gradual introduction of West Syriac liturgy and script to the Malabar Coast, a process that continued through the 19th century.

The arrival of Mar Gregorios in 1665, marked the introduction of Oriental Orthodoxy in the Malankara Church and valid Bishopric of Syriac Orthodox Church in India.

In 1912, a Catholicate was instituted in Malankara by the Syriac orthodox Patriarch Abdul Masih, thereby starting a century of legal proceedings between factions of the church which supported the Catholicate, and those who opposed it on behalf of the claims that, the Abdul Masih was excommunicated, Later Syriac Orthodox Church established Canonical Catholicate / Maphrianate of the East in India renamed to Catholicos of India of the Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church

The Malankara Church experienced a series of splits over the centuries, resulting in the formation of several churches, some of which embraced the jurisdiction of foreign churches, while others remained autocephalous and autonomous churches.

The churches that share the Malankara Church tradition are:

- Jacobite Syrian Christian Church: an Autonomous oriental orthodox church under the local jurisdiction of the Maphrian / Catholicos as known as Catholicos of India of the Syriac Orthodox Church.

- Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church: an Autonomous and autocephalous oriental orthodox church.[52] Catholicos of the East and Malankara Metropolitan entroned on the apostolic throne of Saint Thomas is the primate of the church.

- Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church: an Independent and autonomous Oriental Protestant malankara church under the jurisdiction of Marthoma Metropolitan, and also sharing an communion with the Church of England and its communion.

- Syro-Malankara Catholic Church: a self-governing Eastern Catholic church within the Catholic communion.

- Malabar Independent Syrian Church: an autonomous and autocephalous church under the jurisdiction of its own independent Metropolitan, and also sharing an communion with the Church of England and its communion.

See also

Notes

- Fernando, Leonard; Gispert-Sauch, G. (2004). Christianity in India: Two Thousand Years of Faith. p. 79. ISBN 9780670057696.

The community of the St Thomas Christians was now divided into two: one group known as the Roman Catholic Syrians/RCSC' remained in the new communion with the Western Church and in obedience to the Pope whose authority they recognized in the archbishop of Goa. The 'Malankara Nazranies'stayed with Native head Mar Thoma I and eventually started relation with the West Syrian Church of Antioch

- Robert Eric Frykenberg (2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. p. 361. ISBN 9780198263777.

His followers kept the ancient name ie 'Malankara Nazranies', as distinct from the 'Roman Catholic Syrians' , the name by which the Catholic party became known.

- Hans J. Hillerbrand (2004). Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set. Routledge. ISBN 9781135960285.

those who rejected the Latin rite were known as the New Party, which later became the Jacobite Church

- Malankara Syriac Church

- Gregorios & Roberson, p. 285.

- Vadakkekara, p. 91.

- Stephen Neill (2017). A History of Christianity in India: 1707-1858. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780521893329.

- George Alexander, Jeevan Philip (2020). Malankara Nasrani Research Papers. Lulu.com. pp. 26–27.

- Claudius Buchanan (1812). Christian researches in Asia. Lindney. pp. 107–123.

- Addai and Mari, Liturgy of. Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. 2005

- Gouvea, Antonio de (1606). Jornada. Coimbra.

- Neill 2002, p. 70.

- Vadakkekara, p. 92.

- G. Krishnan Nadar (2001). Historiography and History of Kerala. Learners Book House. p. 82.

- Korah thomas, Antony (1993). The Christians of Kerala. University of Michigan. p. 97.

- "Mulanthuruthy Synod Decisions". www.syriacchristianity.info. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- D.V. Chitaley (1959). All India Reporter. D.V. Chitaley. p. 39.

- "Malankara church row: All you need to know about century-old dispute between Jacobite, Orthodox factions in Kerala". FirstPost. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Frykenberg, p. 109.

- Frykenberg, p. 136.

- Joseph, p. 27.

- Menachery G; 1973, 1982, 1998; Leslie Brown, 1956

- Baum & Winkler, p. 52.

- McVey, Kathleen E (trans) (1989). Ephrem the Syrian: hymns. Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-3093-9.

- Frykenberg, pp. 102–107; 115.

- Baum & Winkler, p. 53.

- Syrian Christians of Kerala- SG Pothen- page 32–33 ( 1970)

- Sreedhara Menon, A. A Survey of Kerala History.(Mal).Page 54.

- NSC Network (2007),The Plates and the Privileges of Syrian Christians Brown L (1956)- The Indian Christians of St. Thomas-Pages 74.75, 85 to 90, Mundanadan (1970),SG Pothen (1970)

- http://marthoma.in/the-church/heritage/

- Vadakkekara, pp. 271–272.

- Vadakkekara, pp. 271.

- Vadakkekara, p. 272.

- Baum & Winkler, p. 105.

- Vadakkekara, p. 274.

- Frykenberg, pp. 122–124.

- Frykenberg, pp. 125–127.

- Frykenberg, p. 127.

- Frykenberg, pp. 127–128.

- Frykenberg, p. 130.

- Frykenberg, pp. 130–133.

- Frykenberg, p. 134.

- Neill 2004, pp. 208–210.

- Neill 2004, p. 214.

- Frykenberg, p. 367.

- Neill 2004, p. 316.

- Neill 2004, p. 317.

- Neill 2004, p. 319.

- Frykenberg, p. 368.

- Claudius Buchanan 1811 ., Menachery G; 1973, 1982, 1998; Podipara, Placid J. 1970; Leslie Brown, 1956; Tisserant, E. 1957; Michael Geddes, 1694;

- Dr. Thekkedath, History of Christianity in India"

- http://www.cnewa.org/default.aspx?ID=9&pagetypeID=9&sitecode=hq&pageno=1

References

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Chaput, Pascale (1999). "La Double identité des chrétiens keralais : confessions et castes chrétiennes au Kerala (Inde du Sud) / The Double Identity of Kerala Christians: Confessions and Christian Castes (South India)". Archives des sciences sociales des religions. 106: 5–23. doi:10.3406/assr.1999.1084.

- Fernando, Leonard; Gispert-Sauch, G. (2004). Christianity in India: Two Thousand Years of Faith. Viking.

- Frykenberg, Eric (2008). Christianity in India: from Beginnings to the Present. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-826377-5.

- Gregorios, Paulos; Roberson, Ronald G. (2008). "Syrian Orthodox Churches in India". In Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milič; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. 5. William B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Hough, James (1893) "The History of Christianity in India".

- T. K. Joseph (1955). Six St. Thomases of South India. University of California.

- Menachery, G (1973) The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India, Ed. George Menachery, B.N.K. Press, vol. 2, ISBN 81-87132-06-X, Lib. Cong. Cat. Card. No. 73-905568 ; B.N.K. Press

- Menachery, G (ed); (1998) "The Indian Church History Classics", Vol.I, The Nazranies, Ollur, 1998. ISBN 81-87133-05-8

- Menachery, G (2010) The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India, Ed. George Menachery, Ollur, vol. 3, ISBN 81-87132-06-X, Lib. Cong. Cat. Card. No. 73-905568 ; 680306 India

- Menachery, G (2012) "India's Christian Heritage" The Church History Association of India, Ed. Oberland Snaitang, George Menachery, Dharmaram College, Bangalore

- Neill, Stephen (2002). A History of Christianity in India: 1707–1858. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521893321. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54885-3. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- Puthiakunnel, Thomas (1973) "Jewish colonies of India paved the way for St. Thomas", The Saint Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India, ed. George Menachery, Vol. II., Trichur.

- Vadakkekara, Benedict (2007). Origin of Christianity in India: a Historiographical Critique. Media House Delhi.