Korean imperial titles

Korean emperors were monarchs in the history of Korea who used the title of emperor or an equivalent.

Three Kingdoms of Korea

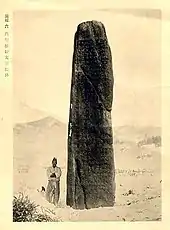

The 5th century was a period of great interaction on the Korean Peninsula that marked the first step toward the unification of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[3] The earliest known tianxia view of the world in Korean history is recorded in Goguryeo epigraphs dating to this period.[4][lower-alpha 1]

Dongmyeong of Goguryeo was a god-king, the Son of Heaven, and his kingdom was the center of the world.[7][lower-alpha 2] As the descendants of the Son of Heaven, the kings of Goguryeo were the Scions of Heaven (Korean: 천손; Hanja: 天孫), who had supreme authority and sacerdotally intermediated between Heaven and Earth.[9] The Goguryeo concept of tianxia was significantly influenced by the original Chinese concept, but its foundation laid in Dongmyeong.[10] In contrast to the Chinese tianxia, which was based on the Mandate of Heaven, the Goguryeo tianxia was based on divine ancestry.[11] As Goguryeo became centralized, Dongmyeong became the state god of Goguryeo.[12] His worship was widespread among the people, and the view that Goguryeo was the center of the world was not limited to the royal family and aristocracy.[13] Dongmyeong was worshiped well into the Goryeo period of Korea; Yi Gyubo said "Even unlettered country folk can tell the tale of King [Dongmyeong]."[14]

Goguryeo was an authority unto itself.[6] It had an independent sphere of influence in Northeast Asia for more than 200 years around the 5th and 6th centuries.[15] Goguryeo viewed itself as the Land of the Scion of Heaven and viewed its neighboring states of Baekje, Silla, and Eastern Buyeo as tributary states.[13][lower-alpha 3] Together, they constituted a Goguryeo tianxia.[17] A strong sense of commonality emerged, later culminating in a "Samhan" consciousness among the peoples of the Three Kingdoms.[18] The Three Kingdoms of Korea were collectively called the Samhan in the Sui and Tang dynasties.[19] Earlier, Goguryeo was called Samhan in the Book of Wei.[20] The unification of the Samhan was later proclaimed by Silla in the 7th century and Goryeo in the 10th century.[21][22]

Goguryeo monarchs were called kings, not emperors.[23] Goguryeo kings were sometimes elevated to "great kings", "holy kings", or "greatest kings".[23][lower-alpha 4] They were equivalent to emperors and khagans.[25] The Goguryeo title of "greatest king", or taewang (Korean: 태왕; Hanja: 太王), was similar to the Chinese title of "heavenly king".[26] "King" was first used in Goguryeo around the beginning of the Common Era; it was first used in Northeast Asia in the 4th century BCE in Old Joseon, before "emperor", or huangdi, was first used in China.[27] The indigenous titles of ga, gan, and han, which were similar to khan, were downgraded and the sinified title of king, or wang, became the supreme title in Northeast Asia.[28] Goguryeo monarchs being called kings was not in deference to China; wang was not inferior to huangdi or khan in Goguryeo tradition.[29]

Goguryeo had a pluralistic concept of tianxia.[31] The Goguryeo tianxia was one among others that constituted the world.[32] During the 5th and 6th centuries, a balance of power was maintained in East Asia between the Northern and Southern dynasties, the Rouran Khaganate, Goguryeo, and, later, Tuyuhun.[15] Goguryeo maintained tributary relations with the Northern and Southern dynasties;[33] the relationships were voluntary and profitable.[34] A policy of coexistence was pursued and relations were peaceful.[32] Goguryeo's tributary relations with the Northern and Southern dynasties were nominal.[32] The Northern and Southern dynasties had no control over Goguryeo's foreign policy; Goguryeo pursued policies that went against Chinese interests.[15] Goguryeo restrained Northern Wei, the strongest power in East Asia at the time, by allying with its enemies.[33] Northern Wei said that Goguryeo was "worthy" and gave preferential treatment to its envoys.[35] Southern Qi said that Goguryeo was "so strong that it [would not] follow orders".[15] Goguryeo maintained cordial relations with the Rouran, and together attacked the Didouyu.[36]

The Goguryeo tianxia was distinct from those of China and Inner Asia.[32] China and Goguryeo recognized each other's spheres of influence.[32] China did not directly intervene in Goguryeo's tianxia of Northeast Asia,[32] and vice versa.[37] Goguryeo did not have westward ambitions, and instead moved its capital to Pyongyang in the 5th century.[38] Within its sphere of influence, Goguryeo partially subjugated the Khitan, Mohe, and Didouyu, and influenced Buyeo, Silla, and Baekje.[39] Peace was maintained with China for more than 150 years;[40] it ended with the unification of China by the Sui dynasty.[41] The unification of China changed the international balance of power.[41] With its supremacy in Northeast Asia threatened, Goguryeo warred with a unified China for 70 years until its defeat in 668 by the Tang dynasty and Silla.[41]

Silla's systems were based on those of Goguryeo.[42] "Great king" was first used in Silla in the early 6th century as Silla expanded.[43][lower-alpha 5] Previously, maripgan, or "highest khan", was used; during its maripgan period (356–514), Silla was unified but not centralized.[45] While the Goguryeo royalty and aristocracy were associated with the Son of Heaven, the Silla royalty and aristocracy were associated with the Buddha.[42] Silla monarchs were viewed as the Buddha and Silla was viewed as a Buddha land from the early 6th century to the mid-7th century.[46] Silla used its own era names during this period.[47] Silla began building an imperial Buddhist temple called the Temple of the Imperial Dragon in the mid-6th century.[48] "Great king" was last used in Silla by Muyeol of Silla; afterward, Silla accommodated itself to the tianxia of the Tang dynasty.[49]

Goryeo

Taejo of Goryeo founded Goryeo in 918 as a successor to Goguryeo.[51] He adopted the era name of "Bestowed by Heaven".[52] Taejo was acknowledged as the successor to Dongmyeong in China.[53] Goryeo was acknowledged as the successor to Goguryeo in China and Japan.[54] Taejo unified Korea and proclaimed the unification of the "Samhan", or the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[22] Goryeo viewed its Three Kingdoms heritage as nearly on a par with the imperial heritage of China.[6] The conceptual world of the Samhan or the "Three Han"—Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje—constituted a Goryeo tianxia.[53] Within the Goryeo tianxia, called Haedong or "East of the Sea", Goryeo monarchs were emperors and Sons of Heaven.[53]

Goryeo monarchs were called emperors and Sons of Heaven.[55] Imperial titles were used since the beginning of the dynasty; Taejo was called "Son of Heaven" by the last king of Silla.[56] Goryeo monarchs addressed imperial edicts and were addressed as "Your Imperial Majesty" (Korean: 폐하; Hanja: 陛下).[57] They were posthumously bestowed with imperial temple names.[55] The use of imperial language was widespread and ubiquitous in Goryeo.[58] Imperial titles and practices extended to members of the royal family.[57] Members of the royal family were commonly invested as kings.[52] Goryeo monarchs wore imperial yellow clothing.[59] Goryeo's imperial system was modeled after that of the Tang dynasty.[52] The government consisted of three departments and six ministries and the military consisted of five armies.[52] Kaesong was an imperial capital and the main palace was an imperial palace; Pyongyang and Seoul were secondary capitals.[60][lower-alpha 6] Goryeo maintained a tributary system.[62] The Jurchens who later founded the Jin dynasty viewed Goryeo as a parent country and Goryeo monarchs as suzerains.[62] Goryeo monarchs were initially called "Emperor of Goryeo" by the Jin dynasty.[63] The Song dynasty, the Liao dynasty, and the Jin dynasty were well aware of and tolerated Goryeo's imperial claims and practices.[64]

Goryeo had a pluralistic concept of tianxia.[65] The Goryeo tianxia was one among others that constituted the world.[65] During the 11th and part of the 12th centuries, a balance of power was maintained in East Asia between Goryeo, the Liao dynasty, the Song dynasty, and Western Xia.[66] Goryeo played an active role in East Asian politics.[67] Goryeo monarchs were called kings vis-à-vis China;[68] Goryeo successively maintained tributary relations with the Five Dynasties (beginning with the Later Tang dynasty), the Song dynasty, the Liao dynasty, and the Jin dynasty. However, Goryeo's tributary relations with them were nominal.[69] Goryeo had no political, economic, or military obligations to China.[70] According to Peter Yun: "While Goryeo may have admired and adopted many of China's culture and institutions, there is little evidence that it accepted the notion of Chinese political superiority as the natural order of things."[71] Goryeo monarchs possessed full de jure sovereignty.[53] During the 11th and 12th centuries, Goryeo was assertive toward China.[67] Goryeo treated imperial envoys from the Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties as equals, not superiors;[64][72] imperial envoys were consistently downgraded.[73]

Goryeo used both a royal and an imperial system during its early and middle periods.[72][lower-alpha 7] Goryeo monarchs were not strictly emperors at home and kings abroad: Goryeo's royal system was also used at home, and its imperial system was also used abroad.[75] They were used almost indiscriminately.[76][lower-alpha 8] Goryeo's identity was not defined by its monarchs being kings or emperors but, instead, by them being Sons of Heaven.[78] According to Remco E. Breuker: "The [Goryeo] ruler has been king, he has been emperor, and at times he was both. His correct appellation is not important, however, compared to the fact that he was considered to rule his own domain [tianxia]; his own, not just politically and practically, but also ideologically and ontologically."[79] Goryeo was an independent tianxia; within it, Goryeo monarchs were Sons of Heaven, called "Son of Heaven of East of the Sea" (Korean: 해동천자; Hanja: 海東天子), who were viewed as superhuman beings who alone mediated between Heaven and the Korean people.[80]

The Goryeo worldview partly originated during earlier periods of Korean history.[81] It was possibly a continuation of the Goguryeo worldview.[81] New elements were introduced during the Goryeo period.[82] The Goryeo worldview was more influenced than was the Goguryeo worldview by Confucianism.[83] Confucianism was the main political ideology during the Goryeo period, but not during the Three Kingdoms period.[83] According to Edward Y. J. Chung: "[Confucianism] played a subordinate role to the traditional ideas and institutions maintained by noble families and hereditary aristocrats, as well as by the Buddhist tradition."[84] The Goryeo worldview was possibly influenced by Dongmyeong worship and Balhae refugees:[81] Dongmyeong was highly venerated and widely worshiped in Goryeo.[85][86] He was the only one among the progenitors of the Three Kingdoms of Korea who was honored with shrines; his tomb and shrine in Pyongyang were called the Real Pearl Tomb and the Shrine of Holy Emperor Dongmyeong.[87] Balhae used imperial titles and era names.[88][89] Taejo viewed Balhae as a kin country and accepted many refugees from it;[90] Balhae refugees constituted 10 percent of the Goryeo population.[91]

Goryeo entered a period of military dictatorship similar to a shogunate in the late 12th century.[92] During this period of de facto military rule, Goryeo monarchs continued to be viewed as Sons of Heaven and emperors, and Goryeo continued to be viewed as a tianxia.[93] The view of Goryeo as a tianxia inspired a spirit of resistance to the Mongols in the 13th century.[94] Goryeo capitulated to the Mongols after 30 years of war and later became a semiautonomous "son-in-law state" (Korean: 부마국; Hanja: 駙馬國) to the Yuan dynasty in 1270.[64] Goryeo's imperial system ended with Wonjong of Goryeo.[72] During this period of Mongol dominance, Goryeo monarchs were demoted to kings and temple names indicated loyalty to the Yuan dynasty.[64] The Songs of Emperors and Kings and Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms maintained the view of Goryeo as a tianxia.[95] However, the view of Goryeo as a tianxia gradually declined.[95] Goryeo ended its son-in-law status in 1356: Gongmin of Goryeo recovered Ssangseong and declared autonomy.[64] Meanwhile, Neo-Confucianism emerged as the dominant ideology;[95] Confucianism profoundly influenced Korean thought, religion, socio-political systems, and ways of life for the first time in Korean history.[84] The powerful influence of Neo-Confucianism in the twilight of the Goryeo dynasty led to a growing Sinocentric view of Korea as a "little China".[95]

Joseon

The Goryeo dynasty transitioned into the Joseon dynasty in 1392. The architects of the Joseon dynasty were anti-Buddhist Neo-Confucian scholar-officials.[96] They transformed Korea from a Buddhist country into a Confucian country.[97] Joseon was a thoroughly Confucian country;[98] it was the self-proclaimed most and later only Confucian country in the world.[97] The view of Korea as a unification of the "Three Han"—Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje—continued in the Joseon dynasty.[99][100] Sejong the Great built shrines for the progenitors of the Three Kingdoms of Korea;[101] he said that the Three Kingdoms were equal and rejected a proposal to worship only the progenitor of Silla.[102] The view of Korea as a tianxia or a center of the world ended in the Joseon dynasty.[103] Joseon monarchs were kings, not emperors; Joseon viewed China as the only center of the world.[103]

See also

Notes

- The Chungju Goguryeo Monument may date earlier to c. 397, based on an inscription that says: "7th year of Yeongnak".[5] Yeongnak is the era name of Gwanggaeto the Great. Goguryeo used its own era names.[6]

- All foundation myths in Korean mythology feature divine or semidivine origin. Since antiquity, kingship was sacred.[8]

- Buyeo and Silla were legitimate tributary states; Baekje was not.[16]

- "Great King of Goryeo" and "Greatest King of Goryeo" were also used.[24]

- "Greatest king" was also used.[44]

- Gyeongju was previously a secondary capital. The secondary capitals represented the ancient capitals of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[61]

- The royal system was used exclusively during the Seongjong, Mokjong, early Hyeonjong, and late Injong periods. The imperial system was used exclusively during the early Gwangjong period.[72]

- For example, Goryeo used Korean imperial titles and Chinese era names in tandem.[77] Goryeo very rarely used Korean era names.

References

Citations

- Noh 2014, p. 431.

- 최강 (23 August 2004). 100년전에 찍힌 광개토대왕비…설명도 고구려 호태왕릉비. 대한민국 정책브리핑 (in Korean). Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Noh 2014, p. 284.

- Noh 2014, p. 283.

- "중원 고구려비, 광개토왕 때 제작 가능성 커". YTN (in Korean). 20 November 2019.

- Breuker, Koh & Lewis 2012, p. 135.

- Noh 2014, p. 285.

- Breuker, Koh & Lewis 2012, pp. 121–122.

- Noh 2014, p. 286.

- Noh 2014, p. 287.

- Noh 2014, pp. 287–288.

- Noh 2014, p. 290.

- Noh 2014, p. 292.

- Noh 2014, pp. 291–292.

- Noh 2014, p. 301.

- Noh 2014, pp. 292–296.

- Noh 2014, p. 311.

- Noh 2014, p. 310.

- Jeon 2016, p. 7.

- Jeon 2016, p. 6.

- Jeon 2016, p. 27.

- Chung, Ku-bok (1998). 한(韓). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Noh 2014, p. 298.

- 충주 고구려비(忠州高句麗碑). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Jo 2015, p. 72.

- Shinohara 2004, pp. 10–18.

- Noh 2014, pp. 304–306.

- Noh 2014, pp. 305–307.

- Noh 2014, pp. 306–307.

- Choi, Jangyeal. "Bronze Bowl with Inscription of King Gwanggaeto the Great". National Museum of Korea. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Noh 2014, p. 387.

- Noh 2014, p. 308.

- Noh 2014, p. 300.

- Noh 2014, pp. 268–269.

- Noh 2014, p. 273.

- Noh 2014, p. 270.

- Noh 2014, p. 264.

- Noh 2014, p. 304.

- Noh 2014, pp. 273–274.

- Noh 2014, p. 263.

- Noh 2014, p. 280.

- Noh 2014, p. 289.

- Noh 2014, p. 54.

- Kim 2012b, p. 17.

- Lee & Leidy 2013, p. 32.

- Kim 2012a, p. 68.

- 민병하 (1995). 연호(年號). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Nelson 2017, p. 106.

- Kim 2012b, pp. 24–25.

- Ro, Myoungho (2013). 왕건동상(王建銅像). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Kim 2012a, p. 118.

- Breuker 2003, p. 74.

- Em 2013, p. 25.

- Byington, Mark. "The War of Words Between South Korea and China Over An Ancient Kingdom: Why Both Sides Are Misguided". History News Network. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Em 2013, p. 24.

- Ro 1999, p. 8.

- Breuker 2003, p. 53.

- Breuker 2003, pp. 53–54.

- Ro 1999, p. 9.

- Breuker 2010, pp. 156–158.

- Kim 2012a, p. 128.

- Breuker 2003, p. 73.

- Ro 1999, p. 14.

- Em 2013, p. 26.

- Breuker 2003, p. 49.

- Yun 2011, pp. 140–141.

- Breuker 2003, p. 60.

- Ro 1999, pp. 14–15.

- Bielenstein 2005, pp. 182–184.

- Yun 2011, p. 141.

- Yun 2011, p. 143.

- Ro 1999, p. 16.

- Breuker 2003, p. 78.

- Breuker 2010, p. 206.

- Breuker 2010, pp. 137–138.

- Breuker 2010, p. 137.

- Breuker 2010, p. 138.

- Breuker 2003, p. 58.

- Breuker 2003, p. 69.

- Breuker 2003, pp. 56–57.

- Breuker 2003, p. 63.

- Ro 1999, p. 37.

- Ro 1999, pp. 37–38.

- Chung 1995, p. 2.

- Breuker 2010, pp. 74–75.

- Breuker 2010, p. 106.

- Breuker 2010, pp. 107–108.

- Kim 2012a, p. 88.

- 이용범 (1996). 발해(渤海). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- 박종기. 고려사의 재발견: 한반도 역사상 가장 개방적이고 역동적인 500년 고려 역사를 만나다 (in Korean). 휴머니스트. ISBN 978-89-5862-902-3.

- Breuker 2003, p. 82.

- Kim 2012a, p. 160.

- Ro 1999, p. 39.

- Ro 1999, pp. 39–40.

- Ro 1999, p. 40.

- Chung 1995, pp. 10–14.

- Berthrong & Berthrong 2000, p. 170.

- Chung 1995, p. 15.

- Han 2006, p. 340.

- Han 2006, p. 346.

- 이범직. 역대시조제(歷代始祖祭). Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture (in Korean). National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Han 2006, p. 343.

- Em 2013, p. 35.

Sources

- Berthrong, John H.; Berthrong, Evelyn Nagai (2000), Confucianism: A Short Introduction, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1-85168-236-2

- Bielenstein, Hans (2005), Diplomacy and Trade in the Chinese World, 589-1276, Brill, ISBN 978-90-474-0761-4

- Breuker, Remco E. (2003), "Koryŏ as an Independent Realm: The Emperor's Clothes?", Korean Studies, University of Hawai'i Press, 27 (1): 48–84, doi:10.1353/ks.2005.0001

- Breuker, Remco E. (2010), Establishing a Pluralist Society in Medieval Korea, 918-1170: History, Ideology, and Identity in the Koryŏ Dynasty, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-19012-2

- Breuker, Remco; Koh, Grace; Lewis, James B. (2012), "The Tradition of Historical Writing in Korea", in Foot, Sarah; Robinson, Chase F. (eds.), The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 2: 400-1400, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-163693-6

- Chung, Edward Y. J. (1995), The Korean Neo-Confucianism of Yi T'oegye and Yi Yulgok: A Reappraisal of the 'Four-Seven Thesis' and its Practical Implications for Self-Cultivation, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-2276-2

- Em, Henry H. (2013), The Great Enterprise: Sovereignty and Historiography in Modern Korea, Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0-8223-5372-0

- Han, Myung-gi (2006), "Korean and Chinese Intellectuals' recognitions of Koguryo in Choson dynasty", Korean Culture (in Korean), Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies, 38, ISSN 1226-8356

- Jeon, Jin-Kook (2016), "The usage and The Perspective of 'Samhan(三韓)'", The Journal of Korean History (in Korean), The Association for Korean Historical Studies, 173: 1–38

- Jo, Yeongkwang (2015), "Status and Tasks for Study of the Foreign Relations and World View of Koguryo in the Gwanggaeto Stele", Journal of Northeast Asian History (in Korean), Northeast Asian History Foundation, 49: 47–86

- Kim, Jinwung (2012a), A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-00024-8

- Kim, Hung-gyu (March 2012b), translated by Bohnet, Adam, "Defenders and Conquerors: The Rhetoric of Royal Power in Korean Inscriptions from the Fifth to Seventh Centuries", Cross-Currents e-Journal, 2, ISSN 2158-9674

- Lee, Soyoung; Leidy, Denise Patry (2013), Silla: Korea's Golden Kingdom, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 978-1-58839-502-3

- Nelson, Sarah Milledge (2017), Gyeongju: The Capital of Golden Silla, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-315-62740-3

- Noh, Taedon (2014), Korea's Ancient Koguryŏ Kingdom: A Socio-Political History, translated by Huston, John, Global Oriental, ISBN 978-90-04-26269-0

- Ro, Myoungho (1999), "The View of the World and the Eastern Emperor in Koryŏ Dynasty", The Journal of Korean History (in Korean), The Association for Korean Historical Studies, 105: 3–40

- Shinohara, Hirokata (2004), "The Title of Taewang(太王) during the Goguryeo(高句麗) Dynasty and the Development of the Perceptions of the Taewang Lineage", The Journal of Korean History (in Korean), The Association for Korean Historical Studies, 125: 1–27

- Yun, Peter (2011), "Balance of Power in the 11th~12th Century East Asian Interstate Relations", Journal of Political Criticism, The Korean Association for Political Criticism, 9: 139–162