Sui dynasty

The Sui dynasty ([swěi], Chinese: 隋朝; pinyin: Suí cháo) was a short-lived imperial dynasty of China of pivotal significance. The Sui unified the Northern and Southern dynasties and reinstalled the rule of ethnic Han in the entirety of China proper, along with sinicization of former nomadic ethnic minorities (Five Barbarians) within its territory. It was succeeded by the Tang dynasty, which largely inherited its foundation.

Sui 隋 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 581–618[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

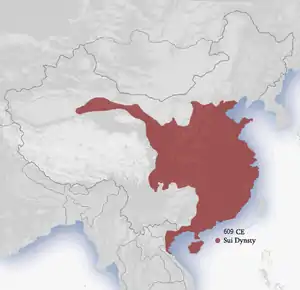

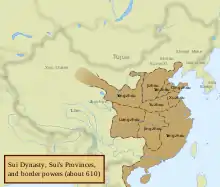

Sui dynasty c.609 | |||||||||||||

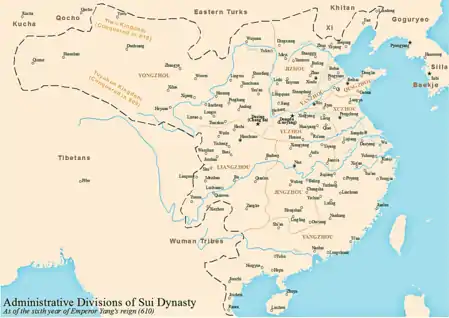

Administrative division of the Sui dynasty circa 610 AD | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Daxing (581–605), Luoyang (605–618) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Chinese | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religion, Zoroastrianism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||

• 581–604 | Emperor Wen | ||||||||||||

• 604–617 | Emperor Yang | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Postclassical Era | ||||||||||||

• Ascension of Yang Jian | 4 March 581 | ||||||||||||

• Abolished by Li Yuan | 23 May 618[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 589 est.[1] | 3,000,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 609 | est. 46,019,956[a] | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Chinese coin, Chinese cash | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Vietnam | ||||||||||||

| Sui dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Sui dynasty" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 隋朝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | ||||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | ||||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | ||||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | ||||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BC | ||||||||

| Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Eastern Zhou | ||||||||

| Spring and Autumn | ||||||||

| Warring States | ||||||||

| IMPERIAL | ||||||||

| Qin 221–207 BC | ||||||||

| Han 202 BC – 220 AD | ||||||||

| Western Han | ||||||||

| Xin | ||||||||

| Eastern Han | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | ||||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | ||||||||

| Jin 266–420 | ||||||||

| Western Jin | ||||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | |||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | ||||||||

| Sui 581–618 | ||||||||

| Tang 618–907 | ||||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | ||||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | |||||||

| Song 960–1279 | ||||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | |||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | Western Liao | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | ||||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | ||||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | ||||||||

| MODERN | ||||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | ||||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | ||||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | ||||||||

Founded by Emperor Wen of Sui, the Sui dynasty capital was Chang'an (which was renamed Daxing, modern Xi'an, Shaanxi) from 581–605 and later Luoyang (605–618). Emperors Wen and his successor Yang undertook various centralized reforms, most notably the equal-field system, intended to reduce economic inequality and improve agricultural productivity; the institution of the Five Departments and Six Board (五省六曹 or 五省六部) system, which is a predecessor of Three Departments and Six Ministries system; and the standardization and re-unification of the coinage. They also spread and encouraged Buddhism throughout the empire. By the middle of the dynasty, the newly unified empire entered a golden age of prosperity with vast agricultural surplus that supported rapid population growth.

A lasting legacy of the Sui dynasty was the Grand Canal.[2] With the eastern capital Luoyang at the center of the network, it linked the west-lying capital Chang'an to the economic and agricultural centers of the east towards Jiangdu (now Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and Yuhang (now Hangzhou, Zhejiang), and to the northern border near modern Beijing. While the pressing initial motives were for shipment of grains to the capital, transporting troops, and military logistics, the reliable inland shipment links would facilitate domestic trade, flow of people and cultural exchange for centuries. Along with the extension of the Great Wall, and the construction of the eastern capital city of Luoyang, these mega projects, led by an efficient centralized bureaucracy, would amass millions of conscripted workers from the large population base, at heavy cost of human lives.

After a series of costly and disastrous military campaigns against Goguryeo, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea,[3][4][5] ended in defeat by 614, the dynasty disintegrated under a series of popular revolts culminating in the assassination of Emperor Yang by his minister, Yuwen Huaji in 618. The dynasty, which lasted only thirty-seven years, was undermined by ambitious wars and construction projects, which overstretched its resources. Particularly, under Emperor Yang, heavy taxation and compulsory labor duties would eventually induce widespread revolts and brief civil war following the fall of the dynasty.

The dynasty is often compared to the earlier Qin dynasty for unifying China after prolonged division. Wide-ranging reforms and construction projects were undertaken to consolidate the newly unified state, with long-lasting influences beyond their short dynastic reigns.

History

Emperor Wen and the founding of Sui

Towards the late Northern and Southern dynasties, the Northern Zhou conquered the Northern Qi in 577 and reunified northern China. The century's trend of gradual conquest of the southern dynasties of the Han Chinese by the northern dynasties, which were ruled by ethnic minority Xianbei, would become inevitable. By this time, the later founder of the Sui dynasty, Yang Jian, an ethnic Han Chinese, became the regent to the Northern Zhou court. His daughter was the Empress Dowager, and her stepson, Emperor Jing of Northern Zhou, was a child. After crushing an army in the eastern provinces, Yang Jian usurped the throne to become Emperor Wen of Sui. While formerly the Duke of Sui when serving at the Zhou court, where the character "Sui 隨" literally means "to follow" and implies loyalty, Emperor Wen created the unique character "Sui (隋)", morphed from the character of his former title, as the name of his newly founded dynasty. In a bloody purge, he had fifty-nine princes of the Zhou royal family eliminated, yet nevertheless became known as the "Cultured Emperor".[6] Emperor Wen abolished the anti-Han policies of Zhou and reclaimed his Han surname of Yang. Having won the support of Confucian scholars who held power in previous Han dynasties (abandoning the nepotism and corruption of the nine-rank system), Emperor Wen initiated a series of reforms aimed at strengthening his empire for the wars that would reunify China.

In his campaign for southern conquest, Emperor Wen assembled thousands of boats to confront the naval forces of the Chen dynasty on the Yangtze River. The largest of these ships were very tall, having five layered decks and the capacity for 800 non-crew personnel. They were outfitted with six 50-foot-long booms that were used to swing and damage enemy ships, or to pin them down so that Sui marine troops could use act-and-board techniques.[6]:89 Besides employing Xianbei and other Chinese ethnic groups for the fight against Chen, Emperor Wen also employed the service of people from southeastern Sichuan, which Sui had recently conquered.[6]:89

In 588, the Sui had amassed 518,000 troops along the northern bank of the Yangtze River, stretching from Sichuan to the East China Sea.[7] The Chen dynasty could not withstand such an assault. By 589, Sui troops entered Jiankang (Nanjing) and the last emperor of Chen surrendered. The city was razed to the ground, while Sui troops escorted Chen nobles back north, where the northern aristocrats became fascinated with everything the south had to provide culturally and intellectually.

Although Emperor Wen was famous for bankrupting the state treasury with warfare and construction projects, he made many improvements to infrastructure during his early reign. He established granaries as sources of food and as a means to regulate market prices from the taxation of crops, much like the earlier Han dynasty. The large agricultural surplus supported rapid growth of population to a historical peak, which was only surpassed at the zenith of the Tang Dynasty more than a century later.

The state capital of Chang'an (Daxing), while situated in the militarily secure heartland of Guanzhong, was remote from the economic centers to the east and south of the empire. Emperor Wen initiated the construction of the Grand Canal, with completion of the first (and the shortest) route that directly linked Chang'an to the Yellow River (Huang He). Later, Emperor Yang enormously enlarged the scale of the Grand Canal construction.

Externally, the emerging nomadic Turkic (Tujue) Khaganate in the north posed a major threat to the newly founded dynasty. With Emperor Wen's diplomatic maneuver, the Khaganate split into Eastern and Western halves. Later the Great Wall was consolidated to further secure the northern territory. In Emperor Wen's late years, the first war with Goguryeo (Korea), ended with defeat. Nevertheless, the celebrated "[Reign of Kaihuang" (era name of Emperor Wen)" was considered by historians as one of the apexes in the two millennium imperial period of Chinese history.

The Sui Emperors were from the northwest military aristocracy, and emphasized that their patrilineal ancestry was ethnic Han, claiming descent from the Han official Yang Zhen.[8] The New Book of Tang traced his patrilineal ancestry to the Zhou dynasty kings via the Dukes of Jin.[9]

The Yang of Hongnong 弘農楊氏[10][11][12][13][14] were asserted as ancestors by the Sui Emperors, much as the Longxi Li's were asserted as ancestors of the Tang Emperors.[15] The Li of Zhaojun and the Lu of Fanyang hailed from Shandong and were related to the Liu clan which was also linked to the Yang of Hongnong and other clans of Guanlong.[16] The Dukes of Jin were claimed as the ancestors of the Hongnong Yang.[17]

The Yang of Hongnong, Jia of Hedong, Xiang of Henei, and Wang of Taiyuan from the Tang dynasty were claimed as ancestors by Song dynasty lineages.[18]

Information about these major political events in China were somehow filtered west and reached the Byzantine Empire, the continuation of the Roman Empire in the east. From Turkic peoples of Central Asia the Eastern Romans derived a new name for China after the older Sinae and Serica: Taugast (Old Turkic: Tabghach), during its Northern Wei (386–535) period.[19] The 7th-century Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta wrote a generally accurate depiction of the reunification of China by Emperor Wen of Sui Dynasty, with the conquest of the rival Chen Dynasty in southern China. Simocatta correctly placed these events within the reign period of Byzantine ruler Maurice.[20] Simocatta also provided cursory information about the geography of China, its division by the Yangzi River and its capital Khubdan (from Old Turkic Khumdan, i.e. Chang'an) along with its customs and culture, deeming its people "idolatrous" but wise in governance.[20] He noted that the ruler was named "Taisson", which he claimed meant "Son of God", perhaps Chinese Tianzi (Son of Heaven) or even the name of the contemporary ruler Emperor Taizong of Tang.[21]

Emperor Yang and the reconquest of Vietnam

Emperor Yang of Sui (569–618) ascended the throne after his father's death, possibly by murder. He further extended the empire, but unlike his father, did not seek to gain support from the nomads. Instead, he restored Confucian education and the Confucian examination system for bureaucrats. By supporting educational reforms, he lost the support of the nomads. He also started many expensive construction projects such as the Grand Canal of China, and became embroiled in several costly wars. Between these policies, invasions into China from Turkic nomads, and his growing life of decadent luxury at the expense of the peasantry, he lost public support and was eventually assassinated by his own ministers.

Both Emperors Yang and Wen sent military expeditions into Vietnam as Annam in northern Vietnam had been incorporated into the Chinese empire over 600 years earlier during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD). However the Kingdom of Champa in central Vietnam became a major counterpart to Chinese invasions to its north. According to Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais, these invasions became known as the Linyi-Champa Campaign (602–605).[6]

The Hanoi area formerly held by the Han and Jin dynasties was easily retaken from the Early Lý dynasty ruler Lý Phật Tử in 602. A few years later the Sui army pushed farther south and was attacked by troops on war elephants from Champa in southern Vietnam. The Sui army feigned retreat and dug pits to trap the elephants, lured the Champan troops to attack then used crossbows against the elephants causing them to turn around and trample their own soldiers. Although Sui troops were victorious many succumbed to disease as northern soldiers did not have immunity to tropical diseases such as malaria.[6]:90

Goguryeo-Sui wars

The Sui dynasty led a series of massive expeditions to invade Goguryeo, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Emperor Yang conscripted many soldiers for the campaign. This army was so enormous it recorded in historical texts that it took 30 days for all the armies to exit their last rallying point near Shanhaiguan before invading Goguryeo. In one instance the soldiers—both conscripted and paid—listed over 3000 warships, up to 1.15 million infantry, 50,000 cavalry, 5000 artillery, and more. The army stretched to 1000 li or about 410 km (250 mi) across rivers and valleys, over mountains and hills. Each of the four military expeditions ended in failure, incurring a substantial financial and manpower deficit from which the Sui would never recover.

Fall of the Sui Dynasty

One of the major work projects undertaken by the Sui was construction activities along the Great Wall of China; but this, along with other large projects, strained the economy and angered the resentful workforce employed. During the last few years of the Sui dynasty, the rebellion that rose against it took many of China's able-bodied men from rural farms and other occupations, which in turn damaged the agricultural base and the economy further.[23] Men would deliberately break their limbs in order to avoid military conscription, calling the practice "propitious paws" and "fortunate feet."[23] Later, after the fall of Sui, in the year 642, Emperor Taizong of Tang made an effort to eradicate this practice by issuing a decree of a stiffer punishment for those who were found to deliberately injure and heal themselves.[23]

Although the Sui dynasty was relatively short (581–618), much was accomplished during its tenure. The Grand Canal was one of the main accomplishments. It was extended north from the Hangzhou region across the Yangzi to Yangzhou and then northwest to the region of Luoyang. Again, like the Great Wall works, the massive conscription of labor and allocation of resources for the Grand Canal project resulted in challenges for Sui dynastic continuity. The eventual fall of the Sui dynasty was also due to the many losses caused by the failed military campaigns against Goguryeo. It was after these defeats and losses that the country was left in ruins and rebels soon took control of the government. Emperor Yang was assassinated in 618. He had gone South after the capital being threatened by various rebel groups and was killed by his advisors (Yuwen Clan). Meanwhile, in the North, the aristocrat Li Yuan (李淵) held an uprising after which he ended up ascending the throne to become Emperor Gaozu of Tang. This was the start of the Tang dynasty, one of the most-noted dynasties in Chinese history.

There were Dukedoms for the offspring of the royal families of the Zhou dynasty, Sui dynasty, and Tang dynasty in the Later Jin (Five Dynasties).[24] This practice was referred to as Èr wángsānkè (二王三恪).

Culture

Although the Sui dynasty was relatively short-lived, in terms of culture, it represents a transition from the preceding ages, and many cultural developments which can be seen to be incipient during the Sui dynasty later were expanded and consolidated during the ensuing Tang dynasty, and later ages. This includes not only the major public works initiated, such as the Great Wall and the Great Canal, but also the political system developed by Sui, which was adopted by Tang with little initial change other than at the top of the political hierarchy. Other cultural developments of the Sui dynasty included religion and literature, particular examples being Buddhism and poetry.

Rituals and sacrifices were conducted by the Sui.[25]

Buddhism

Buddhism was popular during the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern and Southern dynasties period that preceded the Sui dynasty, spreading from India through Kushan Afghanistan into China during the Late Han period. Buddhism gained prominence during the period when central political control was limited. Buddhism created a unifying cultural force that uplifted the people out of war and into the Sui dynasty. In many ways, Buddhism was responsible for the rebirth of culture in China under the Sui dynasty.

While early Buddhist teachings were acquired from Sanskrit sutras from India, it was during the late Six dynasties and Sui dynasty that local Chinese schools of Buddhist thoughts started to flourish. Most notably, Zhiyi founded the Tiantai school and completed the Great treatise on Concentration and Insight, within which he taught the principle of "Three Thousand Realms in a Single moment of Life" as the essence of Buddhist teaching outlined in the Lotus Sutra.

Emperor Wen and his empress had converted to Buddhism to legitimize imperial authority over China and the conquest of Chen. The emperor presented himself as a Cakravartin king, a Buddhist monarch who would use military force to defend the Buddhist faith. In the year 601 AD, Emperor Wen had relics of the Buddha distributed to temples throughout China, with edicts that expressed his goals, "all the people within the Four Seas may, without exception, develop enlightenment and together cultivate fortunate karma, bringing it to pass that present existences will lead to happy future lives, that the sustained creation of good causation will carry us one and all up to wondrous enlightenment".[6]:89 Ultimately, this act was an imitation of the ancient Mauryan Emperor Ashoka of India.[6]:89

Confucianism

Confucian philosopher Wang Tong wrote and taught during the Sui Dynasty, and even briefly held office as Secretary of Shuzhou.[26] His most famous (as well as only surviving) work, the Explanation of the Mean (Zhongshuo, 中说)[27] was compiled shortly after his death in 617.

Poetry

Although poetry continued to be written, and certain poets rose in prominence while others disappeared from the landscape, the brief Sui dynasty, in terms of the development of Chinese poetry, lacks distinction, though it nonetheless represents a continuity between the Six Dynasties and the poetry of Tang.[28] Sui dynasty poets include Yang Guang (580–618), who was the last Sui emperor (and a sort of poetry critic); and also, the Lady Hou, one of his consorts.

Rulers

| Posthumous Name (Shi Hao 諡號) Convention: "Sui" + name | Birth Name | Period of Reign | Era Names (Nian Hao 年號) and their according range of years |

| Wéndì (文帝) | Yáng Jiān (楊堅) | 581–604 | Kāihuáng (開皇) 581–600 Rénshòu (仁壽) 601–604 |

| Yángdì (煬帝) or Míngdì (明帝) | Yáng Guǎng (楊廣) | 604–618[lower-alpha 1] | Dàyè (大業) 605–618 |

| Gōngdì (恭帝) | Yáng Yòu (楊侑) | 617–618[lower-alpha 1] | Yìníng (義寧) 617–618 |

| Gōngdì (恭帝) | Yáng Tóng (楊侗) | 618–619[lower-alpha 1] | Huángtài (皇泰) 618–619 |

Family tree of the Sui emperors

| Emperors family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Chinese sovereign

- Extreme weather events of 535–536

- Grand Canal of China

- History of China

- List of tributaries of Imperial China

- List of ancient Chinese

- Anji Bridge

Notes

- In 617, the rebel general Li Yuan (the later Emperor Gaozu of Tang) declared Emperor Yang's grandson Yang You emperor (as Emperor Gong) and "honored" Emperor Yang as Taishang Huang (retired emperor) at the western capital Daxing (Chang'an), but only the commanderies under Li's control recognized this change; for the other commanderies under Sui control, Emperor Yang was still regarded as emperor, not as retired emperor. After news of Emperor Yang's death in 618 reached Daxing and the eastern capital Luoyang, Li Yuan deposed Emperor Gong and took the throne himself, establishing the Tang dynasty, but the Sui officials at Luoyang declared Emperor Gong's brother Yang Tong (later also known as Emperor Gong during the brief reign of Wang Shichong over the region as the emperor of a brief Zheng (鄭) state) emperor. Meanwhile, Yuwen Huaji, the general under whose leadership the plot to kill Emperor Yang was carried out, declared Emperor Wen's grandson Yang Hao emperor but killed Yang Hao later in 618 and declared himself emperor of a brief Xu (許) state. As Yang Hao was completely under Yuwen's control and only "reigned" briefly, he is not usually regarded as a legitimate emperor of Sui, while Yang Tong's legitimacy is more recognized by historians but still disputed.

References

- Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 129. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 1170959.

- CIHoCn, p.114 : " dug between 605 and 609 by means of enormous levies of conscripted labor ".

- "Koguryo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Byeon, Tae-seop (1999) 韓國史通論 (Outline of Korean history), 4th ed, Unknown Publisher, ISBN 89-445-9101-6.

- "Complex of Koguryo Tombs". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Ebrey, Patricia; Walthall, Ann; Palais, James (2009). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-00534-8.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 176.

- Book of Sui, vol. 1

- New Book of Tang, zh:s:新唐書

- Howard L. Goodman (2010). Xun Xu and the Politics of Precision in Third-Century AD China. ISBN 9789004183377.

- Bulletin. The Museum. 1992. p. 154.

- Jo-Shui Chen (2 November 2006). Liu Tsung-yüan and Intellectual Change in T'ang China, 773–819. Cambridge University Press. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-0-521-03010-6.

- Peter Bol (1 August 1994). "This Culture of Ours": Intellectual Transitions in Tang and Sung China. Stanford University Press. pp. 505–. ISBN 978-0-8047-6575-6.

- Asia Major. Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica. 1995. p. 57.

- R. W. L. Guisso (December 1978). Wu Tse-T'len and the politics of legitimation in T'ang China. Western Washington. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-914584-90-2.

- Jo-Shui Chen (2 November 2006). Liu Tsung-yüan and Intellectual Change in T'ang China, 773–819. Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-521-03010-6.

- 《氏族志》

- Peter Bol (1 August 1994). "This Culture of Ours": Intellectual Transitions in T'ang and Sung China. Stanford University Press. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-0-8047-6575-6.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03519-5, p. 168.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. London: Hakluyt Society. Accessed 21 September 2016, pp 29–31.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier (ed.), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. London: Hakluyt Society. Accessed 21 September 2016, p. 29; also footnote #4 on p. 29.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art permanent exhibit notice.

- Benn, 2.

- Ouyang, Xiu (5 April 2004). Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. Richard L. Davis, translator. Columbia University Press. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-231-50228-3.

- John Lagerwey; Pengzhi Lü (30 October 2009). Early Chinese Religion: The Period of Division (220–589 Ad). BRILL. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3.

- Ivanhoe, Philip (2009). Readings from the Lu-Wang school of Neo-Confucianism. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co. p. 149. ISBN 978-0872209602.

- Explanation of the Mean (中說)

-

- Watson, Burton (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4, p. 109.

Further reading

- Wright, Arthur F. (1979). "The Sui dynasty (581–617)". In Twitchett, Dennis (ed.). The Cambridge History of China: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–149. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Wright, Arthur F. (1978). The Sui Dynasty. Knopf. p. 237.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sui Dynasty. |

| Preceded by Northern and Southern dynasties |

Dynasties in Chinese history 581–619 |

Succeeded by Tang dynasty |