Tributary system of China

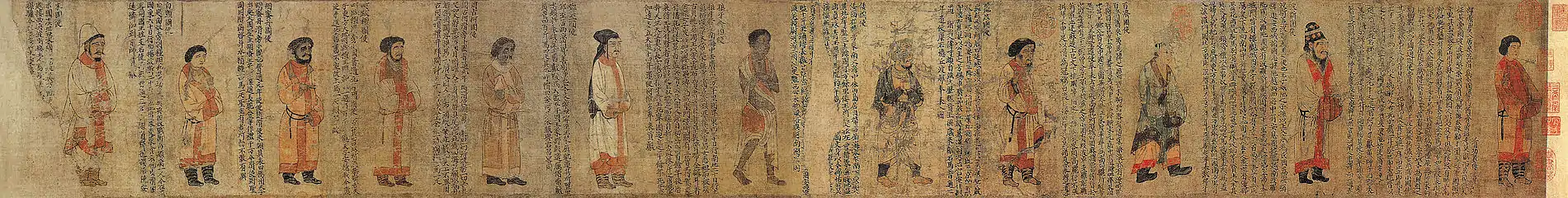

The tributary system of China (simplified Chinese: 中华朝贡体系; traditional Chinese: 中華朝貢體系; pinyin: Zhōnghuá cháogòng tǐxì), or Cefeng system (simplified Chinese: 册封体制; traditional Chinese: 冊封體制; pinyin: Cèfēng tǐzhì) was a network of loose international relations focused on China which facilitated trade and foreign relations by acknowledging China's predominant role in East Asia. It involved multiple relationships of trade, military force, diplomacy and ritual. The other nations had to send a tributary envoy to China on schedule, who would kowtow to the Chinese emperor as a form of tribute, and acknowledge his superiority and precedence. The other countries followed China's formal ritual in order to keep the peace with the more powerful neighbor and be eligible for diplomatic or military help under certain conditions. Political actors within the tributary system were largely autonomous and in almost all cases virtually independent.[1]

Definition

The term "tribute system", strictly speaking, is a Western invention. There was no equivalent term in the Chinese lexicon to describe what would be considered the "tribute system" today, nor was it envisioned as an institution or system. John King Fairbank and Teng Ssu-yu created the "tribute system" theory in a series of articles in the early 1940s to describe "a set of ideas and practices developed and perpetuated by the rulers of China over many centuries." The Fairbank model presents the tribute system as an extension of the hierarchic and nonegalitarian Confucian social order. The more Confucian the actors, the more likely they were to participate in the tributary system.[2]

In practice

The "tribute system" is often associated with a "Confucian world order", under which neighboring states complied and participated in the "tribute system" to secure guarantees of peace, investiture, and trading opportunities.[3] One member acknowledged another's position as superior, and the superior would bestow investiture upon them in the form of a crown, official seal, and formal robes, to confirm them as king.[4] The practice of investing non-Chinese neighbors had been practiced since ancient times as a concrete expression of the loose reign policy.[5] The rulers of Joseon, in particular, sought to legitimize their rule through reference to Chinese symbolic authority. On the opposite side of the tributary relationship spectrum was Japan, whose leaders could hurt their own legitimacy by identifying with Chinese authority.[6] In these politically tricky situations, sometimes a false king was set up to receive investiture for the purposes of tribute trade.[7]

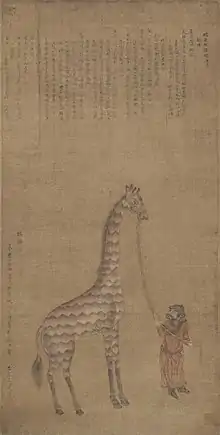

In practice, the tribute system only became formalized during the early years of the Ming dynasty. The "tribute" entailed a foreign court sending envoys and exotic products to the Chinese emperor. The emperor then gave the envoys gifts in return and permitted them to trade in China. Presenting tribute involved theatrical subordination but usually not political subordination. The political sacrifice of participating actors was simply "symbolic obeisance".[8] Actors within the "tribute system" were virtually autonomous and carried out their own agendas despite sending tribute; as was the case with Japan, Korea, Ryukyu, and Vietnam.[9] Chinese influence on tributary states was almost always non-interventionist in nature and tributary states "normally could expect no military assistance from Chinese armies should they be invaded".[10][11] For example, when the Hongwu Emperor learned that the Vietnamese attacked Champa, he only rebuked them,[12] and did not intervene in the 1471 Vietnamese invasion of Champa, which resulted in the destruction of that country. Both Vietnam and Champa were tributary states. When the Malacca sultanate sent envoys to China in 1481 to inform them that while returning to Malacca in 1469 from a trip to China, the Vietnamese had attacked them, castrating the young and enslaving them, China still did not interfere with affairs in Vietnam. The Malaccans reported that Vietnam was in control of Champa and also that the Vietnamese sought to conquer Malacca, but the Malaccans did not fight back because of a lack of permission from the Chinese to engage in war. The Ming emperor scolded them, ordering the Malaccans to strike back with violent force if the Vietnamese attacked.[13]

According to a 2018 study in the Journal of Conflict Resolution covering Vietnam-China relations from 1365 to 1841, "the Vietnamese court explicitly recognized its unequal status in its relations with China through a number of institutions and norms." Due to their participation in the tributary system, Vietnamese rulers behaved as though China was not a threat and paid very little military attention to it. Rather, Vietnamese leaders were clearly more concerned with quelling chronic domestic instability and managing relations with kingdoms to their south and west."[14]

Nor were states that sent tribute forced to mimic Chinese institutions, for example in cases such as the Inner Asians, who basically ignored the trappings of Chinese government. Instead they manipulated Chinese tribute practices for their own financial benefit.[15] The gifts doled out by the Ming emperor and the trade permits granted were of greater value than the tribute itself, so tribute states sent as many tribute missions as they could. In 1372, the Hongwu Emperor restricted tribute missions from Joseon and six other countries to just one every three years. The Ryukyu Kingdom was not included in this list, and sent 57 tribute missions from 1372 to 1398, an average of two tribute missions per year. Since geographical density and proximity was not an issue, regions with multiple kings such as the Sultanate of Sulu benefited immensely from this exchange.[7] This also caused odd situations such as the Turpan Khanate simultaneously raiding Ming territory and offering tribute at the same time because they were eager to obtain the emperor's gifts, which were given in the hope that it might stop the raiding.

Rituals

The Chinese tributary system required a set of rituals from the tributary states whenever they sought relations with China as a way of regulating diplomatic relations.[16] The main rituals generally included:

- The sending of missions by tributary states to China[16]

- The tributary envoys' kowtowing before the Chinese emperor as "a symbolic recognition of their inferiority" and "acknowledgment of their status of a vassal state[16]

- The presentation of tribute and receipt of the emperor's "vassals' gifts"[16]

- The investiture of the tributary state's ruler as the legitimate king of his land[16]

After the completion of the rituals, the tributary states engaged in their desired business, such as trade.[16]

Tributary system of the Qing dynasty

The Manchu-led Qing dynasty invaded the Joseon dynasty of Korea and forced it to become a tributary in 1636, due to Joseon's continued support and loyalty to the Ming dynasty. However, the Manchus, whose ancestors had been subordinate to Korean kingdoms,[17] were viewed as barbarians by the Korean court, which, regarding itself as the new "Confucian ideological center" in place of the Ming, continued to use the Ming calendar in defiance of the Qing, despite sending tribute missions.[18] Meanwhile, Japan avoided direct contact with Qing China and instead manipulated embassies from neighboring Joseon and Ryukyu to make it falsely appear as though they came to pay tribute.[19] Joseon Korea remained a tributary of Qing China until 1895, when the First Sino-Japanese War ended this relationship.

History

Tributary relations emerged during the Tang dynasty as Chinese rulers started perceiving foreign envoys bearing tribute as a "token of conformity to the Chinese world order".[21]

The Ming founder Hongwu Emperor adopted a maritime prohibition policy and issued tallies to "tribute-bearing" embassies for missions. Missions were subject to limits on the number of persons and items allowed.[22]

Japan

In 1404, Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu accepted the Chinese title "King of Japan" while not being the Emperor of Japan. The Shogun was the de facto ruler of Japan. The Emperor of Japan was a weak, powerless figurehead during the feudal shogunate periods of Japan,[23][24] and was at the mercy of the Shogun.[25] For a brief period until Yoshimitsu's death in 1408, Japan was an official tributary of the Ming dynasty. This relationship ended in 1549 when Japan, unlike Korea, chose to end its recognition of China's regional hegemony and cancel any further tribute missions.[26] Yoshimitsu was the first and only Japanese ruler in the early modern period to accept a Chinese title.[27] Membership in the tributary system was a prerequisite for any economic exchange with China; in exiting the system, Japan relinquished its trade relationship with China.[28] Under the rule of the Wanli Emperor, Ming China quickly interpreted the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598) as a challenge and threat to the imperial Chinese tributary system.[29]

Thailand

Thailand was subordinate to China as a vassal or tributary state from the Sui dynasty until the Taiping Rebellion of the late Qing dynasty in the mid-19th century.[30] The Sukhothai Kingdom, the first unified Thai state, established official tributary relations with the Yuan dynasty during the reign of King Ram Khamhaeng, and Thailand remained a tributary of China until 1853.[31] Wei Yuan, the 19th century Chinese scholar, considered Thailand to be the strongest and most loyal of China's Southeast Asian tributaries, citing the time when Thailand offered to directly attack Japan to divert the Japanese in their planned invasions of Korea and the Asian mainland, as well as other acts of loyalty to the Ming dynasty.[32] Thailand was welcoming and open to Chinese immigrants, who dominated commerce and trade, and achieved high positions in the government.[33]

Vietnam

The Chinese domination of Vietnam lasted 1050 years, and when it finally ended in 938, Vietnam became a tributary of China until 1885 when it became a protectorate of France with the Treaty of Tientsin (1885).[34] The Lê dynasty (1428–1527) and Nguyễn Dynasty (1802–1945) adopted the Imperial Chinese system, with rulers declaring themselves Emperors on the Confucian model and attempting to create a Vietnamese Imperial tributary system while still remaining a tributary state of China.[35]

Maritime Southeast Asia

The Sultanate of Malacca and the Sultanate of Brunei, sent tribute to the Ming dynasty, with their first rulers personally travelling to China with the Imperial fleets. The Samudera Pasai Sultanate and Majapahit also sent tribute missions.[36][37]

See also

References

Citations

- Chu 1994, p. 177.

- Lee 2017, pp. 28-29.

- Lee 2017, p. 9.

- Lee 2017, p. 13.

- Lee 2017, p. 33.

- Lee 2017, p. 3.

- Smits 2019, p. 65.

- Lee 2017, p. 12.

- Lee 2017, p. 15-16.

- Smits 2019, p. 35.

- de Klundert 2013, p. 176.

- Edward L. Dreyer (1982). Early Ming China: a political history, 1355-1435. Stanford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-8047-1105-4. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Straits Branch, Reinhold Rost (1887). Miscellaneous papers relating to Indo-China: reprinted for the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society from Dalrymple's "Oriental Repertory," and the "Asiatic Researches" and "Journal" of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume 1. Trübner & Co. p. 252. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- David C. Kang, et al. "War, Rebellion, and Intervention under Hierarchy: Vietnam–China Relations, 1365 to 1841." Journal of Conflict Resolution 63.4 (2019): 896-922. online

- Lee 2017, p. 17.

- Khong, Y. F. (2013). "The American Tributary System". The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 6 (1): 1–47. doi:10.1093/cjip/pot002. ISSN 1750-8916.

- Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives https://books.google.com/books?id=6p1NCgAAQBAJ&lpg=PA36&pg=PA36#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Lee 2017, p. 23.

- Lee 2017, p. 24.

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, pp. 45–47, ISBN 978-0231139243

- Lee 2017, p. 18.

- 2014, p. 19.

- "Emperor Akihito steps down, marking the end of three-decade Heisei era"; Walter Sim Japan Correspondent; https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/japan-emperor-to-step-down-today-in-first-abdication-for-two-centuries

- The Emperors of Modern Japan; edited by Ben-Ami Shillony; BRILL, 2008; page 1; https://books.google.com/books?id=FwztKKtQ_rAC&lpg=PA1&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

- The Yamato Dynasty: The Secret History of Japan's Imperial Family; By Sterling Seagrave, Peggy Seagrave; Broadway Books, 2001; Page 23; https://books.google.com/books?id=Se8UzqKr2x8C&lpg=PA23&pg=PA23#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Howe, Christopher. The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy: Development and Technology in Asia. p. 337

- Lee 2017, p. 19.

- Fogel, Tributary system of China, p. 27, at Google Books; Goodrich, Luther Carrington et al. (1976). Dictionary of Ming biography, 1368–1644,, p. 1316, at Google Books; note: the economic benefit of the Sinocentric tribute system was profitable trade. The tally trade (kangō bōeki or kanhe maoyi in Chinese) was a system devised and monitored by the Chinese – see Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric et al. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia, p. 471.

- Swope, Kenneth. "Beyond Turtleboats: Siege Accounts from Hideyoshi's Second Invasion of Korea, 1597–1598" (PDF). Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies: 761. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2013-09-07.

At this point in 1593, the war entered a stalemate during which intrigues and negotiations failed to produce a settlement. As the suzerain of Joseon Korea, Ming China exercised tight control over the Koreans during the war. At the same time, Ming China negotiated bilaterally with Japan while often ignoring the wishes of the Korean government.

- Gambe, Annabelle R. (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 99. ISBN 9783825843861. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Chinvanno, Anuson (1992-06-18). Thailand's Policies towards China, 1949–54. Springer. p. 24. ISBN 9781349124305. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Leonard, Jane Kate (1984). Wei Yuan and China's Rediscovery of the Maritime World. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 137–138. ISBN 9780674948556. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Gambe, Annabelle R. (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9783825843861. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ASEAN and the Rise of China; Ian Storey; Routledge 2013; page 102 https://books.google.com/books?id=WO59snyW0HIC&lpg=PA102&pg=PA102#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Alexander Woodside (1971). Vietnam and the Chinese model: a comparative study of Vietnamese and Chinese government in the first half of the nineteenth century (reprint, illustrated ed.). Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 234. ISBN 0-674-93721-X. Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- Anthony Reid (2010). Imperial Alchemy: Nationalism and Political Identity in Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0521872379.

- Marie-Sybille de Vienne (2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. NUS Press. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-9971698188.

Sources

- Chu, Samuel C. (1994), Liu Hung-Chang and China's Early Modernization, Routledge

- Lee, Ji-Young (2017), China's Hegemony: Four Hundred Years of East Asian Domination, Columbia University Press

- Smits, Gregory (1999), Visions of Ryukyu: identity and ideology in early-modern thought and politics, Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2037-1, retrieved June 20, 2011

- de Klundert, Theo van (2013), Capitalism and Democracy: A Fragile Alliance, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited

- Rossabi, Morris (Oct 15, 1976). "Mansur". In Goodrich, L Carrington (ed.). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644, Association for Asian Studies. 2. Columbia University Press. pp. 1037–1038. ISBN 0-231-03801-1. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

Further reading

- Cohen, Warren I. . East Asia at the Center : Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. ISBN 0231101082.

- Fairbank, John K., and Ssu-yu Teng. "On the Ch'ing tributary system." Harvard journal of Asiatic studies 6.2 (1941): 135–246. online

- Kang, David C., et al. "War, Rebellion, and Intervention under Hierarchy: Vietnam–China Relations, 1365 to 1841." Journal of Conflict Resolution 63.4 (2019): 896–922. online

- Kang, David C. "International Order in Historical East Asia: Tribute and Hierarchy Beyond Sinocentrism and Eurocentrism." International Organization (2019): 1-29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818319000274

- Song, Nianshen (Summer 2012). "'Tributary' from a Multilateral and Multilayered Perspective". Chinese Journal of International Politics. 5 (2): 155–182. doi:10.1093/cjip/pos005. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Smits, Gregory (2019), Maritime Ryukyu, 1050-1650, University of Hawaii Press

- Swope, Kenneth M. "Deceit, Disguise, and Dependence: China, Japan, and the Future of the Tributary System, 1592–1596." International History Review 24.4 (2002): 757–782.

- Wills, John E. Past and Present in China's Foreign Policy: From "Tribute System" to "Peaceful Rise". (Portland, ME: MerwinAsia, 2010. ISBN 9781878282873.

- Womack, Brantly. "Asymmetry and China's tributary system." Chinese Journal of International Politics 5.1 (2012): 37–54. online

- Zhang, Yongjin, and Barry Buzan. "The tributary system as international society in theory and practice." Chinese Journal of International Politics 5.1 (2012): 3-36.