Kukri

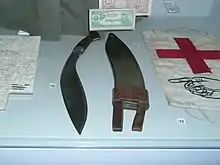

The kukri (English: /ˈkʊkri/)[2] or khukuri (Nepali: खुकुरी, pronounced [kʰukuri]) is a type of machete originating from the Indian subcontinent, and is traditionally associated with the Nepali-speaking Gurkhas of Nepal and India. The knife has a distinct recurve in its blade. It serves multiple purposes as a melee weapon and also as a regular cutting tool throughout most of South Asia. The blade has traditionally served the role of a basic utility knife for the Gurkhas. The kukri is the national weapon of Nepal, and consequently is a characteristic weapon of the Nepalese Army. The kukri also sees standard service with various regiments and units within the Indian Army, such as the Assam Rifles, the Kumaon Regiment, the Garhwal Rifles and the various Gorkha regiments. Outside of its native region of South Asia, the kukri also sees service with the Royal Gurkha Rifles of the British Army—a unique regiment that is quite different from the rest of the British Army as it is the only regiment that recruits its soldiers strictly from Nepal; a relationship that has its roots in the times of British colonial rule in India.[3][4] The kukri is the staple weapon of all Gurkha military regiments and units throughout the world, so much so that some English-speakers refer to the weapon as a "Gurkha blade" or "Gurkha knife".[5] The kukri often appears in Nepalese and Indian Gorkha heraldry and is used in many traditional, Hindu-centric rites such as wedding ceremonies.[6]

| Kukri | |

|---|---|

A polished kukri | |

| Type | Bladed melee weapon, utility tool |

| Place of origin | Indian subcontinent |

| Service history | |

| In service | c. 7th century – present[1] |

| Used by | Gurkhas (natively) |

| Wars | |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 450–900 g (1–2 lb) |

| Length | 40–45 cm (16–18 in) |

There have been, and still are many myths surrounding the kukri since its earliest recorded use in the 7th century—most notably that a traditional custom revolves around the blade in which it must draw blood, owing to its sole purpose as a fighting weapon, before being sheathed. However, they are frequently used as regular utility tools. Extraordinary stories of their use in combat by Gurkhas may contribute to this misconception.[7][8] The kukri, khukri, and kukkri spellings are of Indian English origin,[9] with the original Nepalese English spelling being khukuri.

History

Researchers trace the origins of the blade back to the domestic sickle and the prehistoric bent stick used for hunting and later in hand-to-hand combat.[10] Similar implements have existed in several forms throughout the Indian subcontinent and were used both as weapons and as tools, such as for sacrificial rituals. Burton (1884) writes that the British Museum housed a large kukri-like falchion inscribed with writing in Pali.[11] Among the oldest existing kukri are those belonging to Drabya Shah (c. 1559), housed in the National Museum of Nepal in Kathmandu.

The kukri came to be known to the Western world when the East India Company came into conflict with the growing Gorkha Kingdom, culminating in the Gurkha War of 1814–1816. It gained literary attention in the 1897 novel Dracula by Irish author Bram Stoker. Despite the popular image of Dracula having a stake driven through his heart at the conclusion of a climactic battle between Dracula's bodyguards and the heroes, Mina's narrative describes his throat being sliced through by Jonathan Harker's kukri and his heart pierced by Quincey Morris's Bowie knife.[12]

All Gurkha troops are issued with two kukris, a Service No.1 (ceremonial) and a Service No.2 (exercise); in modern times members of the Brigade of Gurkhas receive training in its use. The weapon gained fame in the Gurkha War and its continued use through both World War I and World War II enhanced its reputation among both Allied troops and enemy forces. Its acclaim was demonstrated in North Africa by one unit's situation report. It reads: "Enemy losses: ten killed, our nil. Ammunition expenditure nil."[13] Elsewhere during the Second World War, the kukri was purchased and used by other British, Commonwealth and US troops training in India, including the Chindits and Merrill's Marauders. The notion of the Gurkha with his kukri carried on through to the Falklands War.

On 2 September 2010, Bishnu Shrestha, a retired Indian Army Gurkha soldier, alone and armed only with a khukri, defeated thirty bandits who attacked a passenger train he was on in India. He was reported to have killed three of the bandits, wounded eight more and forced the rest of the band to flee.[14] A contemporaneous report in the Times of India, that includes an interview with Shrestha, indicates he was less successful.[15]

Design

The kukri is designed primarily for chopping. The shape varies a great deal from being quite straight to highly curved with angled or smooth spines. There are substantial variations in dimensions and blade thickness depending on intended tasks as well as the region of origin and the smith that produced it. As a general guide the spines vary from 5–10 mm (3⁄16–3⁄8 in) at the handle, and can taper to 2 mm (1⁄16 in) by the point while the blade lengths can vary from 26–38 cm (10–15 in) for general use.

A kukri designed for general purpose is commonly 40–45 cm (16–18 in) in overall length and weighs approximately 450–900 g (1–2 lb). Larger examples are impractical for everyday use and are rarely found except in collections or as ceremonial weapons. Smaller ones are of more limited utility, but very easy to carry.

Another factor that affects its weight and balance is the construction of the blade. To reduce weight while keeping strength, the blade might be hollow forged, or a fuller is created. Kukris are made with several different types of fuller including tin Chira (triple fuller), Dui Chira (double fuller), Ang Khola (single fuller), or basic non-tapered spines with a large bevelled edge.

Kukri blades usually have a notch (karda, kauda, Gaudi, Kaura, or Cho) at the base of the blade. Various reasons are given for this, both practical and ceremonial: that it makes blood and sap drop off the blade rather than running onto the handle and thereby prevent the handle from becoming slippery;[16] that it delineates the end of the blade whilst sharpening; that it is a symbol representing a cows' foot, or Shiva; that it can catch another blade or kukri in combat. The notch may also represent the teats of a cow, a reminder that the kukri should not be used to kill a cow, an animal revered and worshipped by Hindus. The notch may also be used as a catch, to hold tight against a belt, or to bite onto twine to be suspended.

The handles are most often made of hardwood or water buffalo horn, but ivory, bone, and metal handles have also been produced. The handle quite often has a flared butt that allows better retention in draw cuts and chopping. Most handles have metal bolsters and butt plates which are generally made of brass or steel.

The traditional handle attachment in Nepal is the partial tang, although the more modern versions have the stick tang which has become popular. The full tang is mainly used on some military models but has not become widespread in Nepal itself.

The kukri typically comes in either a decorated wooden scabbard or one which is wrapped in leather. Traditionally, the scabbard also holds two smaller blades: an unsharpened checkmark to burnish the blade, and another accessory blade called a karda. Some older style scabbards include a pouch for carrying flint or dry tinder.

Manufacture

The Biswakarma Kami (caste) are the traditional inheritors of the art of kukri-making.[17] Modern kukri blades are often forged from spring steel, sometimes collected from recycled truck suspension units.[17] The tang of the blade usually extends all the way through to the end of the handle; the small portion of the tang that projects through the end of the handle are hammered flat to secure the blade. Kukri blades have a hard, tempered edge and a softer spine. This enables them to maintain a sharp edge, yet tolerate impacts.

Kukri handles, usually made from hardwood or buffalo horn, are often fastened with a kind of tree sap called laha (also known as "Himalayan epoxy"). With a wood or horn handle, the tang may be heated and burned into the handle to ensure a tight fit, since only the section of handle which touches the blade is burned away. In more modern kukri, handles of cast aluminium or brass are press-fitted to the tang; as the hot metal cools it shrinks, locking onto the blade. Some kukri (such as the ones made by contractors for the modern Indian Army), have a very wide tang with handle slabs fastened on by two or more rivets, commonly called a full tang (panawal) configuration.

Traditional profiling of the blade edge is performed by a two-man team; one spins a grinding wheel forwards and backwards by means of a rope wound several times around an axle while the sharpener applies the blade. The wheel is made by hand from fine river sand bound by laha, the same adhesive used to affix the handle to the blade. Routine sharpening is traditionally accomplished by passing a chakmak over the edge in a manner similar to that used by chefs to steel their knives.

Kukri scabbards are usually made of wood or metal with an animal skin or metal or wood covering. The leather work is often done by a Sarki.

Uses

.jpg.webp)

Weaponry

The kukri is effective as a chopping weapon, due to its weight, and slashing weapon, because the curved shape creates a "wedge" effect which causes the blade to cut effectively and deeper. Because the blade bends towards the opponent, the user need not angle the wrist while executing a chopping motion. Unlike a straight-edged sword, the center of mass combined with the angle of the blade allow the kukri to slice as it chops. The edge slides across the target's surface while the center of mass maintains momentum as the blade moves through the target's cross-section. This gives the kukri a penetrative force disproportional to its length. The design enables the user to inflict deep wounds and to penetrate bone.

Utility

While most famed from use in the military, the kukri is the most commonly used multipurpose tool in the fields and homes in Nepal. Its use has varied from building, clearing, chopping firewood, digging, slaughtering animals for food, cutting meat and vegetables, skinning animals, and opening cans. Its use as a general farm and household tool disproves the often stated "taboo" that the weapon cannot be sheathed "until it has drawn blood".[18]

The kukri is versatile. It can function as a smaller knife by using the narrower part of the blade, closest to the handle. The heavier and wider end of the blade, towards the tip, functions as an axe or a small shovel.

Anatomy

Blade

- Keeper (Hira Jornu): Spade/diamond shaped metal/brass plate used to seal the butt cap.

- Butt Cap (Chapri): Thick metal/brass plate used to secure the handle to the tang.

- Tang (Paro): Rear piece of the blade that goes through the handle.

- Bolster (Kanjo): Thick metal/brass round shaped plate between blade and handle made to support and reinforce the fixture.

- Spine (Beet): Thickest blunt edge of the blade.

- Fuller/Groove (Khol): Straight groove or deep line that runs along part of the upper spine.

- Peak (Juro): Highest point of the blade.

- Main body (Ang): Main surface or panel of the blade.

- Fuller (Chirra): Curvature/hump in the blade made to absorb impact and to reduce unnecessary weight.

- Tip (Toppa): The starting point of the blade.

- Edge (Dhaar): Sharp edge of the blade.

- Belly (Bhundi): Widest part/area of the blade.

- Bevel (Patti): Slope from the main body until the sharp edge.

- Notch (Cho): A distinctive cut (numeric '3 '-like shape) in the edge. Used as a stopper when sharpening with the chakmak.

- Ricasso (Ghari): Blunt area between the notch and bolster.

- Rings (Harhari): Round circles in the handle.

- Rivet (Khil): Steel or metal bolt to fasten or secure tang to the handle.

- Tang Tail (Puchchar): Last point of the kukri blade.

Scabbard

- Frog (Faras): Belt holder specially made of thick leather (2 mm to 4 mm) encircling the scabbard close towards the throat.

- Upper Edge (Mathillo Bhaag): Spine of the scabbard where holding should be done when handling a kukri.

- Lace (Tuna): A leather cord used to sew or attach two ends of the frog. Especially used in army types.

- Main Body (Sharir): The main body or surface of the scabbard. Generally made in semi oval shape.

- Chape (Khothi): Pointed metallic tip of the scabbard. Used to protect the naked tip of a scabbard.

- Loop (Golie): Round leather room/space where a belt goes through attached/fixed to the keeper with steel rivets.

- Throat (Mauri): Entrance towards the interior of the scabbard for the blade.

- Strap/Ridge (Bhunti): Thick raw leather encircling the scabbard made to create a hump to secure the frog from moving or wobbling (not available in this pic).

- Lower Edge (Tallo Bhag): Belly/curvature of the scabbard.

Classification

Kukris can be broadly classified into two types: Eastern and Western. The Eastern blades are originated and named according to the towns and villages of Eastern Nepal. The Eastern Khukuris are Angkhola Khukuri, Bhojpure Khukuri, Chainpure Khukuri, Cheetlange (Chitlange) Khukuri, Chirwa (Chiruwa) Khukuri, Dhankute Khukuri, Ganjawla Khukuri, Panawala Khukuri, Sirupate Khukuri translates as Siru grass leaf like.[19] Khukuris made in locations like Chainpur, Bhojpur, and Dhankuta in Eastern Nepal are excellent and ornate knives.[20] Western blades are generally broader. Occasionally the Western style is called Budhuna, (referring to a fish with a large head), or baspate (bamboo leaf) which refers to blades just outside the proportions of the normal Sirupate blade. Despite the classification of Eastern and Western, both styles of kukri appear to be used in all areas of Nepal.

There is Khukuri named after Gorkhali General Amar Singh Thapa called Amar Singh Thapa Khukuri. This Khukuri is modelled on the real Khukuri used by the Gorkhali General.[21] The real Khukuri used by Amar Singh Thapa is archived at National Museum of Nepal and is more curvy in nature than other traditions.[22]

Legacy

There is a popular proverb in Nepali as follows:

Sirupate Khukuri ma Laha chha ki chhaina?

Translation: Does your Sirupate Khukuri have enough iron?

References

- "Kukri History: Khukuri House". www.khukuriblades.com. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "Kukri | Meaning of Kukri by Lexico". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Patial, R.C. (17 October 2019). "Knowing The Khukri". Salute To The Indian Soldier − Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Dutta, Sujan (19 July 2019). "I Witnessed the Kargil War. That's Why I Won't Celebrate It". The Wire − India. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Gurung, Tim I. (6 April 2018). "A brief history of the Gurkha's knife – the kukri". Asia Times. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "BBC - A History of the World - Object : The Fisher Kukri". www.bbc.co.uk. 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Association, Victoria Cross and George Cross. "The VC and GC Association". vcgca.org. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Latter, Mick (26 March 2013). "The Kukri". Welcome to the Gurkha Brigade Association. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Illustrated Oxford Dictionary. Great Britain: Dorling Kindersley. 1998. ISBN 140532029-X.

- Richard Francis Burton (1987). The Book of the Sword. London: Dover. ISBN 0-486-25434-8.

- "The Book of the Sword, by Richard F. Burton—A Project Gutenberg eBook". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Stoker, Dacre and Ian Holt (2009). Dracula the Un-Dead. Penguin Group. p. 306.

- Reagan, Geoffrey (1992). Military Anecdotes. Guinness Publishing. ISBN 0-85112-519-0. p. 180.

- "Lone Nepali Gorkha who subdued 40 train robbers", República, 13 January 2011. Archived 22 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Soldier takes on dacoits on train; Gang Of 30", Times of India, Times News Network, 4 September 2010.

- Wooldridge, Ian (20 November 1989). "Episode 3". In the Highest Tradition. Event occurs at 13 minutes 25 seconds. BBC. BBC Two. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

Here if I may describe, you see a little pattern there, which some people say that it has got some religious significance, but I doubt very much. In fact, that is just so that when you have blood on the kukri, it just sort of naturally drips there, it doesn't get onto your hand and starts clogging up and that is what it is for, that little nick there.

- "Kamis, Khukuri makers of Nepal". himalayan-imports.com. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Latter, Mick (26 March 2013). "The Kukri". Welcome to the Gurkha Brigade Association. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Kukri Mart - Handmade Genuine Gurkhas Knives and original Nepalese Khukuris".

- Visit Nepal '98: By The Official Travel Manual of Visit Nepal '98 VNY'98 Secretariat, 1998

- "Wednesday evening with Amar Singh Thapa Khukuri". bladeforums.com. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Weapons (Kukri, Katar, Kora) of Amar Singh Thapa in National Museum of Nepal, Kathmandu". pinterest.com. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

External links

Media related to Kukri at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kukri at Wikimedia Commons- Kukri at the Encyclopædia Britannica