Sgian-dubh

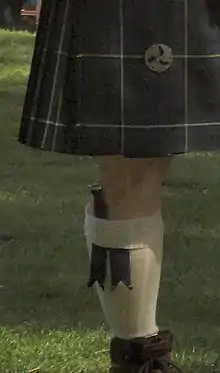

The sgian-dubh (/ˌskiːən ˈduː/ skee-ən-DOO; Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [s̪kʲənˈt̪u]) is a small, single-edged knife (Scottish Gaelic: sgian) worn as part of traditional Scottish Highland dress along with the kilt. Originally used for eating and preparing fruit, meat, and cutting bread and cheese, as well as serving for other more general day-to-day uses such as cutting material and protection, it is now worn as part of traditional Scottish dress tucked into the top of the kilt hose with only the upper portion of the hilt visible. The sgian-dubh is normally worn on the same side as the dominant hand.

Etymology and spelling

The name comes from the Scottish Gaelic sgian-dubh. Although the primary meaning of dubh is "black", the secondary meaning of "hidden" is at the root of sgian-dubh, based on the stories and theories surrounding the knife's origin, in particular those associated with the Highland custom of depositing weapons at the entrance to a house prior to entering as a guest. Compare also other Gaelic word-formations such as dubh-sgeir "underwater skerry" (lit. black skerry), dubh-fhacal "riddle" (lit. hidden word), dubh-cheist "enigma" (lit. hidden question).

Despite this practice, a small twin edged-dagger, (a mattucashlass), concealed under the armpit, combined with a smaller knife, (sgian-dubh), concealed in the hose or boot, would offer an element of defence or of surprise if employed in attack.

As sgian is feminine, the form sgian dhubh might be expected, since a feminine noun causes initial consonant lenition in a following adjective, and indeed the everyday modern Gaelic for a normal 'black knife' is sgian dhubh. However, the term for the ceremonial knife is a set-phrase containing a fossilized historical form. In older Gaelic, a system of blocked lenition meant that lenition did not occur when the adjective started with a consonant of the same group as the final consonant of the noun, and n and d are both dental in Gaelic.

Various alternative spellings are found in English, including "skene-dhu" and "skean-dhu".[1]

The anglicised plural is most commonly sgian-dubhs (in its various spellings) but sgians-dubh is also occasionally encountered. The proper Gaelic plural forms (e.g. sgianan-dubha) are only rarely encountered in English usage.

Origins

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

The sgian-dubh may have evolved from the sgian-achlais, a dagger that could be concealed under the armpit. Used by the Scots of the 17th and 18th centuries, this knife was slightly larger than the average modern sgian-dubh and was carried in the upper sleeve or lining of the body of the jacket.[2]

Courtesy and etiquette would demand that when entering the home of a friend, any concealed weapons would be revealed. It follows that the sgian-achlais would be removed from its hiding place and displayed in the stocking top held securely by the garters.[3]

The sgian-dubh also resembles the small skinning knife that is part of the typical set of hunting knives. These sets contain a butchering knife with a 9-to-10-inch (23 to 25 cm) blade, and a skinner with a blade of about 4 inches (10 cm). These knives usually had antler handles, as do many early sgian-dubhs. The larger knife is likely the ancestor of the modern dirk.[4][5][6]

Bog oak, jet black in appearance, was a very hard wood suitable for the purpose. The handles on the stag knives simulate horn which was also traditionally used. Any ornamentation is merely a reflection of the Highlander's lack of confidence in paper money which resulted in him embellishing much of his personal wearing apparel with silver and cairngorm stones which are of value. Thus he carried on his person most of his worldly wealth. The black dagger (sgian-dubh) was usually carried in a place of concealment very often under his armpit (or oxter). This gives support to the view that 'black' does not refer only to the colour of the handle but implies 'covert' – as in (as stated previously) blackmail or black market. When the Highlander visited a house on his travels having deposited all his other weapons at the front door he did not divest himself of his concealed dagger, since in these days it was unsafe to be ever totally unarmed, not because he feared his host but rather because he feared intrusions from outside. Accordingly, although retaining the dagger; out of courtesy to his host he removed it from its place of concealment and put it somewhere where his host could see it, invariably in his stocking on the side of his dominant hand (right- or left-handed).

The sgian-dubh can be seen in portraits of kilted men of the mid-19th century. A portrait by Sir Henry Raeburn of Colonel Alasdair Ranaldson MacDonell of Glengarry hangs in the National Gallery of Scotland; it shows hanging from his belt on his right hand side a Highland Scottish dirk, and visible at the top of his right stocking what appears to be a nested set of two sgian-dubhs. A similar sgian-dubh is in the collection of The National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland.[7]

Construction

The early blades varied in construction, some having a "clipped" (famously found on the Bowie knife) or "drop" point. The "spear-point" tip has now become universal. The earliest known blades, some housed in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, are made from German or Scandinavian steel, which was highly prized by the Highlanders. Scalloped filework on the back of the blade is common on all Scottish knives. A short blade of 3 to 3.5 inches (7.5 to 9 cm) is typical.

Traditionally the scabbard is made of leather reinforced with wood and fitted with mounts of silver or some other metal which may be cast or engraved with designs ranging from Scottish thistles, Celtic knotwork, or heraldic elements such as a crest. While this makes for more popular and expensive knives, the sheath is hidden from view in the stocking while the sgian-dubh is worn. The sheaths of many modern sgian-dubhs are made of plastic mounted with less expensive metal fittings.

Since the modern sgian-dubh is worn mainly as a ceremonial item of dress and is usually not employed for cutting food or self-defence, blades are often of a simple (but not unglamorous) construction. These are typically made from stainless steel. The hilts used on many modern sgian-dubhs are made of plastic that has been molded to resemble carved wood and fitted with cast metal mounts and synthetic decorative stones. Some are not even knives at all, but a plastic handle and sheath cast as one piece. Other examples are luxurious and expensive art pieces, with hand-carved ebony or bog wood hilts, sterling silver fittings and may have pommels set with genuine cairngorm stones and blades of Damascus steel or etched with Celtic designs or heraldic motifs.

Legality

When worn as part of the national dress of Scotland, the sgian-dubh is legal in Scotland, England, and Wales: in Scotland under the Criminal Law (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act 1995 sec. 49, sub-sec. 5(c);[8] in England and Wales under the Criminal Justice Act 1988 (sec. 139)[9] and the Offensive Weapons Act 1996 (sec. 4).[10]

However, the wearing of the sgian-dubh is sometimes banned in areas with zero tolerance weapons policies or heightened security concerns. For example, they were banned from a school dance in Scotland,[11] and initially banned for the June 2014 celebration of the Battle of Bannockburn.[12]

Airport security rules now require travellers to put their sgian-dubh in checked-in baggage.

A Montreal bagpiper who got a ticket from police for wearing the knife fought the charge at court. Police gave Jeff McCarthy a $221 ticket for sporting it in his kilt hose while performing at the McGill University convocation ceremony on 2 November 2016.[13] The case was dropped in May 2018 and his knife was returned.[14]

See also

References

- "skene1" Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd edition, 1989. (subscription required).

- Grancsay, Stephen Vincent (1991). Arms & Armor: Essays From the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 1920–1964. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-87099-338-1.

- Ray, R. Celeste (2001). Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South. UNC Press Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-8078-4913-2.

- Blair, Claude (1962). European & American Arms, c. 1100–1850. Virginia: B. T. Batsfords. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7.

- "The Waterford Knife". Irish Archaeology. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Daithi. "Iron Age Ireland". archive.org. Archived from the original on 28 October 2005. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- "Holdings: Three Irish knife-daggers (from Co. Mayo)". nli.ie. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- "Criminal Law (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act 1995". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- "Criminal Justice Act 1988". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- "Offensive Weapons Act 1996". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Arthur MacMillan (26 November 2006). "Top private school bans sgian-dubhs ahead of Christmas dance". The Scotsman. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- No More ‘Sgian Dont!’ Its Sgian Dubh at Bannockburn! clans2014.com. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "Montreal bagpiper to contest ticket for carrying ceremonial knife". Montreal Gazette. 19 November 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- "Ticketed Montreal bagpiper to get ceremonial knife back, have case dropped". Montreal Gazette. 2018-05-19. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sgian dubh. |

| Look up sgian dubh in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Sgian-dubh (Joe D. Huddleston)

- The Skean Dhu (Scotland for Visitors)