LaVeyan Satanism

LaVeyan Satanism is an atheistic religion founded in 1966 by the American occultist and author Anton Szandor LaVey. Scholars of religion have classified it as a new religious movement and a form of Western esotericism. It is one of several different movements that describe themselves as forms of Satanism.

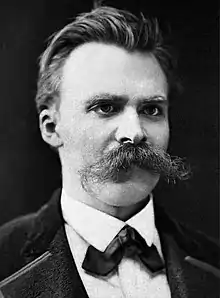

LaVey established LaVeyan Satanism in the U.S. state of California through the founding of his Church of Satan on Walpurgisnacht of 1966, which he proclaimed to be "the Year One", Anno Satanas—the first year of the "Age of Satan". His ideas were heavily influenced by the ideas and writings of Friedrich Nietzsche and Ayn Rand. The church grew under LaVey's leadership, with regional grottos being founded across the United States. A number of these seceded from the church to form independent Satanic organizations during the early 1970s. In 1975, LaVey abolished the grotto system, after which LaVeyan Satanism became a far less organized movement, although it remained greatly influenced by LaVey's writings. In the coming years, members of the church left it to establish their own organisations, also following LaVeyan Satanism, among them John Dewey Allee's First Church of Satan and Karla LaVey's First Satanic Church.

The religion's doctrines are codified in LaVey's book, The Satanic Bible. The religion is materialist, rejecting the existence of supernatural beings, body-soul dualism, and life after death. Practitioners do not believe that Satan literally exists and do not worship him. Instead, Satan is viewed as a positive archetype representing pride, carnality, and enlightenment. He is also embraced as a symbol of defiance against Abrahamic religions, which LaVeyans criticize for suppressing humanity's natural instincts and encouraging irrationality. The religion propagates a naturalistic worldview, seeing mankind as animals existing in an amoral universe. It promotes a philosophy based on individualism and egoism, coupled with Social Darwinism and anti-egalitarianism.

LaVeyan Satanism involves the practice of magic, which encompasses two distinct forms; greater and lesser magic. Greater magic is a form of ritual practice and is meant as psychodramatic catharsis to focus one's emotional energy for a specific purpose. These rites are based on three major psycho-emotive themes: compassion (love), destruction (hate), and sex (lust). Lesser magic is the practice of manipulation by means of applied psychology and glamour (or "wile and guile") to bend an individual or situation to one's will.

Definition

| Part of a series on |

| LaVeyan Satanism |

|---|

|

| Organizations |

| Church of Satan · First Satanic Church · (see also The Black House, Grotto, Council of Nine) |

| Notable people |

| Anton LaVey · Blanche Barton · Peter H. Gilmore · Peggy Nadramia · Diane Hegarty · Karla LaVey |

| Texts |

| The Satanic Bible · The Satanic Rituals · The Satanic Witch · The Devil's Notebook · Satan Speaks! · Letters from the Devil · The Secret Life of a Satanist · The Church of Satan · The Satanic Scriptures |

| Media |

| The Satanic Mass · Satanis: The Devil's Mass · Speak of the Devil: The Canon of Anton LaVey · Satan Takes a Holiday · Strange Music · Death Scenes |

| Related Topics |

| Greater and lesser magic · Satanic holidays · The Black Flame · The infernal names · Enochian Keys · Hail Satan · Sign of the horns · An Interview with Peter H. Gilmore |

LaVeyan Satanism – which is also sometimes termed "Modern Satanism"[1] and "Rational Satanism"[2] – is classified by scholars of religious studies as a new religious movement.[3] When used, "Rational Satanism" is often employed to distinguish the approach of the LaVeyan Satanists from the "Esoteric Satanism" embraced by groups like the Temple of Set.[4] A number of religious studies scholars have also described it as a form of "self-religion" or "self-spirituality",[5] with religious studies scholar Amina Olander Lap arguing that it should be seen as being both part of the "prosperity wing" of the self-spirituality New Age movement and a form of the Human Potential Movement.[6] Conversely, the scholar of Satanism Jesper Aa. Petersen preferred to treat modern Satanism as a "cousin" of the New Age and Human Potential movements.[7]

Religious studies scholar Eugene Gallagher.[8]

The anthropologist Jean La Fontaine described LaVeyan Satanism as having "both elitist and anarchist elements", also citing one occult bookshop owner who referred to the church's approach as "anarchistic hedonism".[9] In their study of Satanism, the religious studies scholars Asbjørn Dyrendal, James R. Lewis, and Jesper Aa. Petersen suggested that LaVey viewed his religion as "an antinomian self-religion for productive misfits, with a cynically carnivalesque take on life, and no supernaturalism".[10] The sociologist of religion James R. Lewis even described LaVeyan Satanism as "a blend of Epicureanism and Ayn Rand's philosophy, flavored with a pinch of ritual magic."[11] The historian of religion Mattias Gardell described LaVey's as "a rational ideology of egoistic hedonism and self-preservation",[12] while Nevill Drury characterised LaVeyan Satanism as "a religion of self-indulgence".[13] It has also been described as an "institutionalism of Machiavellian self-interest".[14]

The Church of Satan rejects the legitimacy of any other organizations who claim to be Satanists, dubbing them "Devil worshipers".[15] Prominent Church leader Blanche Barton described Satanism as "an alignment, a lifestyle".[16] LaVey and the church espoused the view that "Satanists are born, not made";[17] that they are outsiders by their nature, living as they see fit,[18] who are self-realized in a religion which appeals to the would-be Satanist's nature, leading them to realize they are Satanists through finding a belief system that is in line with their own perspective and lifestyle.[19]

Belief

The Satanic Bible

The Satanic Bible has been in print since 1969 and has been translated into various languages.[20] Lewis argued that although LaVeyan Satanists do not treat The Satanic Bible as a sacred text in the way many other religious groups treat their holy texts, it nevertheless is "treated as an authoritative document which effectively functions as scripture within the Satanic community".[11] In particular, Lewis highlighted that many Satanists – both members of the Church of Satan and other groups – quote from it either to legitimize their own position or to de-legitimize the positions of others in a debate.[21] Many other Satanist groups and individual Satanists who are not part of the Church of Satan also recognize LaVey's work as influential.[22]

Many Satanists attribute their conversions or discoveries of Satanism to The Satanic Bible, with 20 percent of respondents to a survey by James Lewis mentioning The Satanic Bible directly as influencing their conversion.[23] For members of the church, the book is said to serve not only as a compendium of ideas but also to judge the authenticity of someone's claim to be a Satanist.[24] LaVey's writings have been described as "cornerstones" within the church and its teachings,[25] and have been supplemented with the writings of its later High Priest, Gilmore, namely his book, The Satanic Scriptures.[25]

The Satanic Bible has been described as the most important document to influence contemporary Satanism.[26] The book contains the core principles of Satanism, and is considered the foundation of its philosophy and dogma.[27] On their website, the Church of Satan urge anyone seeking to learn about LaVeyan Satanism to read The Satanic Bible, stating that doing so is "tantamount to understanding at least the basics of Satanism".[28] Petersen noted that it is "in many ways the central text of the Satanic milieu",[29] with Lap similarly testifying to its dominant position within the wider Satanic movement.[20] David G. Bromley calls it "iconoclastic" and "the best-known and most influential statement of Satanic theology."[30] Eugene V. Gallagher says that Satanists use LaVey's writings "as lenses through which they view themselves, their group, and the cosmos." He also states: "With a clear-eyed appreciation of true human nature, a love of ritual and pageantry, and a flair for mockery, LaVey's Satanic Bible promulgated a gospel of self-indulgence that, he argued, anyone who dispassionately considered the facts would embrace."[31]

Atheism and Satan

LaVey was an atheist, rejecting the existence of all gods.[32] LaVey and his Church do not espouse a belief in Satan as an entity who literally exists,[33] and LaVey did not encourage the worship of Satan as a deity.[34] Instead, the use of Satan as a central figure is intentionally symbolic.[35] LaVey sought to cement his belief system within the secularist world-view that derived from natural science, thus providing him with an atheistic basis with which to criticize Christianity and other supernaturalist beliefs.[36] He legitimized his religion by highlighting what he claimed was its rational nature, contrasting this with what he saw as the supernaturalist irrationality of established religions.[37] He defined Satanism as "a secular philosophy of rationalism and self-preservation (natural law, animal state), giftwrapping these ideas in religious trappings to add to their appeal."[38] In this way, LaVeyan Satanism has been described as an "antireligious religion" by van Luijk.[39] LaVey did not believe in any afterlife.[40]

Man needs ritual and dogma, but no law states that an externalized god is necessary in order to engage in ritual and ceremony performed in a god's name! Could it be that when he closes the gap between himself and his "God" he sees the demon of pride creeping forth—that very embodiment of Lucifer appearing in his midst?

LaVey, The Satanic Bible.[41]

Instead of worshiping the Devil as a real figure, the image of Satan is embraced because of its association with social nonconformity and rebellion against the dominant system.[42] LaVey embraced the iconography of Satan and the label of "Satanist" because it shocked people into thinking,[43] and when asked about his religion, stated that "the reason it's called Satanism is because it's fun, it's accurate and it's productive".[33]

LaVey also conceptualised Satan as a symbol of the individual's own vitality,[44] thus representing an autonomous power within,[45] and a representation of personal liberty and individualism.[46] Throughout The Satanic Bible, the LaVeyan Satanist's view of god is described as the Satanist's true "self"—a projection of his or her own personality—not an external deity.[47] In works like The Satanic Bible, LaVey often uses the terms "god" and "Satan" interchangeably, viewing both as personifications of human nature.[48]

Despite his professed atheism, some passages of LaVey's writings left room for a literal interpretation of Satan, and some members of his Church understood the Devil as an entity that really existed.[49] It is possible that LaVey left some ambivalence in his writings so as not to drive away those Church members who were theistic Satanists.[50] Both LaVey's writings and the publications of the church continue to refer to Satan as if he were a real being, in doing so seeking to reinforce the Satanist's self-interest.[41]

LaVey used Christianity as a negative mirror for his new faith,[51] with LaVeyan Satanism rejecting the basic principles and theology of Christian belief.[9] It views Christianity – alongside other major religions, and philosophies such as humanism and liberal democracy – as a largely negative force on humanity; LaVeyan Satanists perceive Christianity as a lie which promotes idealism, self-denigration, herd behavior, and irrationality.[52] LaVeyans view their religion as a force for redressing this balance by encouraging materialism, egoism, stratification, carnality, atheism, and social Darwinism.[52] LaVey's Satanism was particularly critical of what it understands as Christianity's denial of humanity's animal nature, and it instead calls for the celebration of, and indulgence in, these desires.[9] In doing so, it places an emphasis on the carnal rather than the spiritual.[53]

LaVeyan Satanism

LaVeyan Satanism has been characterised as belonging to the political right rather than to the political left.[54] The historian of Satanism Ruben van Luijk characterised it as a form of "anarchism of the Right".[55] LaVey was anti-egalitarian and elitist, believing in the fundamental inequality of different human beings.[56] His philosophy was Social Darwinist in basis,[57] having been influenced by the writings of Herbert Spencer, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Ayn Rand.[58] LaVey stated that his Satanism was "just Ayn Rand's philosophy with ceremony and ritual added".[59] Characterising LaVey as a Nietzschean, the religious studies scholar Asbjørn Dyrendal nevertheless thought that LaVey's "personal synthesis seems decidedly his own creation, even though the different ingredients going into it are at times very visible."[60] Social Darwinism is particularly noticeable in The Book of Satan, where LaVey uses portions of Redbeard's Might Is Right, though it also appears throughout in references to man's inherent strength and instinct for self-preservation.[37]

For LaVey, the human being was explicitly viewed as an animal,[61] who thus has no purpose other than survival of the fittest, and who therefore exists in an amoral context.[37] He believed that in adopting a philosophical belief in its own superiority above that of the other animals, humankind has become "the most vicious animal of all".[62] For LaVey, non-human animals and children represent an ideal, "the purest form of carnal existence", because they have not been indoctrinated with Christian or other religious concepts of guilt and shame.[63] His ethical views focused around placing oneself and one's family before others, minding one's own business, and – for men – behaving like a gentleman.[64] In responding to threats and harm, he promoted a policy of lex talionis, for instance reversing a Biblical Christian teaching by stating that "if a man smite thee on the one cheek, smash him on the other."[64]

LaVeyan Satanism places great emphasis on the role of liberty and personal freedom.[65] LaVey believed that the ideal Satanist should be individualistic and non-conformist, rejecting what he called the "colorless existence" that mainstream society sought to impose on those living within it.[66] He rejected consumerism and what he called the "death cult" of fashion.[55] He praised the human ego for encouraging an individual's pride, self-respect, and self-realization and accordingly believed in satisfying the ego's desires.[67] He expressed the view that self-indulgence was a desirable trait,[40] and that hate and aggression were not wrong or undesirable emotions but that they were necessary and advantageous for survival.[62] Accordingly, he praised the Seven Deadly Sins as virtues which were beneficial for the individual.[68]

Similarly, LaVey criticized the negative and restrictive attitude to sexuality present in many religions, instead supporting any sexual acts that take place between consenting adults.[69] His Church welcomed homosexual members from its earliest years,[70] and he also endorsed celibacy for those who were asexual.[70] He sought to discourage negative feelings of guilt arising from sexual acts such as masturbation and fetishes,[71] and believed that rejecting these sexual inhibitions and guilt would result in a happier and healthier society.[72] Discussing women, LaVey argued that they should use sex as a tool to manipulate men, in order to advance their own personal power.[73] Conversely, non-consensual sexual relations, such as rape and child molestation, were denounced by LaVey and his Church.[74]

LaVey believed in the imminent demise of Christianity.[75] In addition, he believed that society would enter an Age of Satan, in which a generation living in accordance with LaVeyan principles would come to power.[76] LaVey supported eugenics and expected it to become a necessity in the future, when it would be used to breed an elite who reflected LaVey's "Satanic" principles.[77] In his view, this elite would be "superior people" who displayed the "Satanic" qualities of creativity and nonconformity.[78] He regarded these traits as capable of hereditary transmission, and made the claim that "Satanists are born, not made".[78] He believed that the elite should be siphoned off from the rest of the human "herd", with the latter being forced into ghettoes, ideally "space ghettoes" located on other planets.[79] The anthropologist Jean La Fontaine highlighted an article that appeared in a LaVeyan magazine, The Black Flame, in which one writer described "a true Satanic society" as one in which the population consists of "free-spirited, well-armed, fully-conscious, self-disciplined individuals, who will neither need nor tolerate any external entity 'protecting' them or telling them what they can and cannot do."[34] This rebellious approach conflicts with LaVey's firm beliefs in observing the rule of law.[34]

Magic

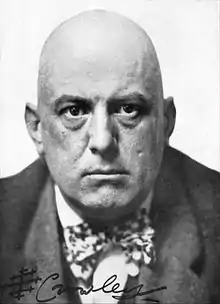

Although LaVey's ideas were largely shaped around a secular and scientific world-view, he also expressed a belief in magic.[80] Rather than characterising magic as a supernatural phenomenon, LaVey expressed the view that it was a part of the natural world thus far undiscovered by scientists.[81] Outlined in The Satanic Bible, LaVey defined magic as "the change in situations or events in accordance with one's will, which would, using normally accepted methods, be unchangeable",[82] a definition that reflects the influence of the British occultist Aleister Crowley.[83] Although he never explained exactly how he believed that this magical process worked,[84] LaVey stated that magicians could successfully utilise this magical force through intensely imagining their desired goal and thus directing the force of their own willpower toward it.[85] He emphasised the idea that magical forces could be manipulated through "purely emotional" rather than intellectual acts.[84]

This practice puts LaVeyan Satanism within a wider tradition of 'high magic' or ceremonial magic,[84] and has also been compared with Christian Science and Scientology.[37] LaVey adopted beliefs and ideas from older magicians but consciously de-Christianised and Satanised them for his own purposes.[86] In presenting himself as applying a scientific perspective on magic, LaVey was likely influenced by Crowley, who had also presented his approach to magic in the same way.[87] However, in contrast to many older ceremonial magicians, LaVey denied that there was any division between black magic and white magic,[88] attributing this dichotomy purely to the "smug hypocrisy and self-deceit" of those who called themselves "white magicians".[89] He similarly differed from many older magicians who emphasised magic as a practice designed to bring about personal transformation and transcendence; rather, for LaVey magic was employer for material gain, personal influence, to harm enemies, and to gain success in love and sex.[90]

LaVey defined his system of magic as greater and lesser magic.[91] Greater magic is a form of ritual practice and is meant as psychodramatic catharsis to focus one's emotional energy for a specific purpose. These rites are based on three major psycho-emotive themes: compassion (love), destruction (hate), and sex (lust).[92] The space in which a ritual is performed is known as an "intellectual decompression chamber",[93] where skepticism and disbelief are willfully suspended, thus allowing the magicians to fully express their mental and emotional needs, holding back nothing regarding their deepest feelings and desires. This magic could then be employed to ensure sexual gratification, material gain, personal success, or to curse one's enemies.[64] LaVey also wrote of "the balance factor", insisting that any magical aims should be realistic.[94] These rituals are often considered to be magical acts,[95] with LaVey's Satanism encouraging the practice of magic to aid one's selfish ends.[96] Much of Satanic ritual is designed for an individual to carry out alone; this is because concentration is seen as key to performing magical acts.[97]

Lesser magic, also referred to an "everyday" or "situational" magic, is the practice of manipulation by means of applied psychology. LaVey defined it as "wile and guile obtained through various devices and contrived situations, which when utilized, can create change in accordance with one's will."[98] LaVey wrote that a key concept in lesser magic is the “command to look”, which can be accomplished by utilizing elements of “sex, sentiment, and wonder”,[99] in addition to the utilization of looks, body language, scents,[100] color, patterns, and odor.[101] This system encourages a form of manipulative role-play, wherein the practitioner may alter several elements of their physical appearance in order to aid them in seducing or "bewitching" on object of desire.[100]

LaVey developed “The Synthesizer Clock”, the purpose of which is to divide humans into distinct groups of people based primarily on body shape and personality traits.[100] The synthesizer is modeled as a clock, and based on concepts of somatotypes.[102] The clock is intended to aid a witch in identifying themselves, subsequently aiding in utilizing the “attraction of opposites” to “spellbind” the witch's object of desire by assuming the opposite role.[100] The successful application of lesser magic is said to be built upon one's understanding of their place on the clock.[103] Upon finding your position on the clock, you are encouraged to adapt it as seen fit, and perfect your type by harmonizing its element for better success.[100] Dyrendal referred to LaVey's techniques as “Erving Goffman meets William Mortensen”.[104] Drawing insights from psychology, biology, and sociology,[105] Petersen noted that lesser magic combines occult and “rejected sciences of body analysis [and] temperaments.”[106]

Basic tenets

The "central convictions" of LaVeyan Satanism are formulated into three lists, which are regularly reproduced within the Church of Satan's written material.[107]

The Nine Satanic Statements

The Nine Satanic Statements are a set of nine assertions made by LaVey in the introductory chapters of The Satanic Bible. They are considered a touchstone of contemporary organized Satanism that constitute, in effect, brief aphorisms that capture Satanic philosophy.[108] The first three statements touch on "indulgence", "vital existence" and "undefiled wisdom" which presents a positive view of the Satanist as a carnal, physical and pragmatic being, where enjoyment of physical existence and an undiluted view of this-worldly truth are promoted as the core values of Satanism, combining elements of Darwinism and Epicureanism. Statement four, five and six deal in matters of ethics, through "kindness to those who deserve it", "vengeance" and "responsibility to the responsible", painting a harsh picture of society and human relations by emphasizing justice rather than love. Statements seven, eight and nine reject the dignity of man, sin and the Christian church. Humans are characterized as "just another animal", traditional "sins" are promoted as means for gratification, and religion as mere business. The adversarial and antinomian aspect of Satan takes precedence in support of statements four through nine, with non-conformity being presented as a core ideal.[109]

- Satan represents indulgence instead of abstinence.

- Satan represents vital existence instead of spiritual pipe dreams.

- Satan represents undefiled wisdom instead of hypocritical self-deceit.

- Satan represents kindness to those who deserve it, instead of love wasted on ingrates.

- Satan represents vengeance instead of turning the other cheek.

- Satan represents responsibility to the responsible instead of concern for psychic vampires.

- Satan represents man as just another animal who, because of his "divine spiritual and intellectual development", has become the most vicious animal of all.

- Satan represents all of the so-called sins, as they all lead to physical, mental, or emotional gratification.

- Satan has been the best friend the Church has ever had, as he has kept it in business all these years.[110]

The Eleven Satanic Rules of the Earth

- Do not give opinions or advice unless you are asked.

- Do not tell your troubles to others unless you are sure they want to hear them.

- When in another's home, show them respect or else do not go there.

- If a guest in your home annoys you, treat him cruelly and without mercy.

- Do not make sexual advances unless you are given the mating signal.

- Do not take that which does not belong to you unless it is a burden to the other person and they cry out to be relieved.

- Acknowledge the power of magic if you have employed it successfully to obtain your desires. If you deny the power of magic after having called upon it with success, you will lose all you have obtained.

- Do not complain about anything to which you need not subject yourself.

- Do not harm little children.

- Do not kill non-human animals unless you are attacked or for your food.

- When walking in open territory, bother no one. If someone bothers you, ask him to stop. If he does not stop, destroy him.[111][112]

Rites and practices

Rituals and ceremonies

LaVey emphasized that in his tradition, Satanic rites came in two forms, neither of which were acts of worship; in his terminology, "rituals" were intended to bring about change, whereas "ceremonies" celebrated a particular occasion.[114] These rituals were often considered to be magical acts,[95] with LaVey's Satanism encouraging the practice of magic to aid one's selfish ends.[96] Much of LaVeyan ritual is designed for an individual to carry out alone; this is because concentration is seen as key to performing magical acts.[97] In The Satanic Bible, LaVey described three types of ritual in his religion: sex rituals designed to attract the desired romantic or sexual partner, compassionate rituals with the intent of helping people (including oneself), and destructive magic which seeks to do harm to others.[95] In designing these rituals, LaVey drew upon a variety of older sources, with scholar of Satanism Per Faxneld noting that LaVey "assembled rituals from a hodgepodge of historical sources, literary as well as esoteric".[115]

LaVey described a number of rituals in his book, The Satanic Rituals; these are "dramatic performances" with specific instructions surrounding the clothing to be worn, the music to be used, and the actions to be taken.[34] This attention to detail in the design of the rituals was intentional, with their pageantry and theatricality intending to engage the participants' senses and aesthetic sensibilities at various levels and enhancing the participants' willpower for magical ends.[116] LaVey prescribed that male participants should wear black robes, while older women should wear black, and other women should dress attractively in order to stimulate sexual feelings among many of the men.[95] All participants are instructed to wear amulets of either the upturned pentagram or the image of Baphomet.[95]

According to LaVey's instructions, on the altar is to be placed an image of Baphomet. This should be accompanied by various candles, all but one of which are to be black. The lone exception is to be a white candle, used in destructive magic, which is kept to the right of the altar.[95] Also to be included are a bell which is rung nine times at the start and end of the ceremony, a chalice made of anything but gold, and which contains an alcoholic drink symbolizing the "Elixir of Life", a sword that represents aggression, a model phallus used as an aspergillum, a gong, and parchment on which requests to Satan are to be written before being burned.[95] Although alcohol was consumed in the church's rites, drunkenness was frowned upon and the taking of illicit drugs was forbidden.[117]

LaVeyan rituals sometimes include anti-Christian blasphemies, which are intended to have a liberating effect on the participants.[95] In some of the rituals, a naked woman serves as the altar; in these cases it is made explicit that the woman's body itself becomes the altar, rather than have her simply lying on an existing altar.[34] In contrast to longstanding stereotypes about Satanists, there is no place for sexual orgies in LaVeyan ritual.[118] Neither animal nor human sacrifice takes place.[119] Children are banned from attending these rituals, with the only exception being the Satanic Baptism, which is specifically designed to involve infants.[34]

LaVey also developed his own Black Mass, which was designed as a form of deconditioning to free the participant from any inhibitions that they developed living in Christian society.[120] He noted that in composing the Black Mass rite, he had drawn upon the work of the French fiction writers Charles Baudelaire and Joris-Karl Huysmans.[121] LaVey openly toyed with the use of literature and popular culture in other rituals and ceremonies, thus appealing to artifice, pageantry, and showmanship.[122] For instance, he published an outline of a ritual which he termed the "Call to Cthulhu" which drew upon the stories of the alien god Cthulhu authored by American horror writer H. P. Lovecraft. In this rite, set to take place at night in a secluded location near to a turbulent body of water, a celebrant takes on the role of Cthulhu and appears before the assembled Satanists, signing a pact between them in the language of Lovecraft's fictional "Old Ones".[123]

Holidays

In The Satanic Bible, LaVey writes that "after one's own birthday, the two major Satanic holidays are Walpurgisnacht and Halloween." Other holidays celebrated by members include the two solstices, the two equinoxes, and Yule.[124][125][126]

Symbolism

As a symbol of his Satanic church, LaVey adopted the upturned five-pointed pentagram.[127] The upturned pentagram had previously been used by the French occultist Eliphas Lévi, and had been adopted by his disciple, Stanislas de Guaita, who merged it with a goat's head in his 1897 book, Key of Black Magic.[127] In the literature and imagery predating LaVey, imagery used to represent the "satanic" is denoted by inverted crosses and blasphemous parodies of Christian art. The familiar goat's head inside an inverted pentagram did not become the foremost symbol of Satanism until the founding of the Church of Satan in 1966.[128] LaVey learned of this variant of the symbol after it had been reproduced on the front cover of Maurice Bessy's coffee table book, Pictorial History of Magic and the Supernatural.[129] Feeling that this symbol embodied his philosophy, LaVey decided to adopt it for his Church.[130] In its formative years, the church utilized this image on its membership cards, stationary, medallions and most notably above the altar in the ritual chamber of the Black House.[131]

During the writing of The Satanic Bible, it was decided that a unique version of the symbol should be rendered to be identified exclusively with the church. LaVey created a new version of Guaita's image, one which was geometrically precise, with two perfect circles surrounding the pentagram, the goat head redrawn, and the Hebrew lettering altered to look more serpentine.[131] LaVey had this design copyrighted to the church,[131] claiming authorship under the pseudonym of "Hugo Zorilla".[132] In doing so, the symbol – which came to be known as the Sigil of Baphomet[133] – came to be closely associated with Satanism in the public imagination.[130]

History

Origins: 1966–72

Although there were forms of religious Satanism that predated the creation of LaVeyan Satanism—namely those propounded by Stanisław Przybyszewski and Ben Kadosh—these had no unbroken lineage of succession to LaVey's form.[134] For this reason, the sociologist of religion Massimo Introvigne stated that "with few exceptions, LaVey is at the origins of all contemporary Satanism".[135] Similarly, the historian Ruben van Luijk claimed that the creation of LaVeyan Satanism marked "the actual beginning of Satanism as a religion such as it is practiced in the world today".[136]

After he came to public attention, LaVey shielded much of his early life in secrecy, and little is known about it for certain.[137] He had been born in Chicago as Howard Stanton Levey in either March or April 1930.[138] He was of mixed Ukrainian, Russian, and German ancestry.[139] He claimed to have worked in the circus and carnival in the years following the Second World War,[140] and in later years, he also alleged that he worked at the San Francisco Orchestra, although this never existed.[140] He also claimed to have had a relationship with a young Marilyn Monroe, although this too was untrue.[141]

By the 1960s he was living at 6114 California Street in San Francisco, a house that he had inherited from his parents.[142] He took an interest in occultism and amassed a large collection of books on the subject.[143] At some point between 1957 and 1960 he began hosting classes at his house every Friday in which lectures on occultism and other subjects were given.[144] Among the topics covered were freaks, extra-sensory perception, Spiritualism, cannibalism, and historical methods of torture.[143] An informal group established around these lectures, which came to be known as the Magic Circle.[145] Among those affiliated with this gathering were the filmmaker and Thelemite occultist Kenneth Anger,[146] and the anthropologist Michael Harner, who later established the core shamanism movement.[146]

LaVey likely began preparations for the formation of his Church of Satan in either 1965 or early 1966,[144] and it was officially founded on Walpurgisnacht 1966.[147] He then declared that 1966 marked Year One of the new Satanic era.[136] It was the first organized church in modern times to be devoted to the figure of Satan,[148] and according to Faxneld and Petersen, the church represented "the first public, highly visible, and long-lasting organisation which propounded a coherent satanic discourse".[3] Its early members were the attendees of LaVey's Magic Circle, although it soon began attracting new recruits.[146] Many of these individuals were sadomasochists or homosexuals, attracted by the LaVeyan openness to different sexual practices.[149] LaVey had painted his house black,[143] with it becoming known as "the Black House",[150] and it was here that weekly rituals were held every Friday night.[146]

LaVey played up to his Satanic associations by growing a pointed beard and wearing a black cloak and inverted pentagram.[13] He added to his eccentric persona by obtaining unusual pets, including a lion that was kept caged in his back garden.[143] Describing himself as the "High Priest of Satan",[151] LaVey defined his position within the church as "monarchical in nature, papal in degree and absolute in power".[152] He led the churches' governing Council of Nine,[152] and implemented a system of five initiatory levels that the LaVeyan Satanist could advance through by demonstrating their knowledge of LaVeyan philosophy and their personal accomplishments in life.[152] These were known as Apprentice Satanist I°, Witch or Warlock II°, Priest or Priestess of Mendes III°, Magister IV°, and Magus V°.[151]

— Per Faxneld and Jesper Petersen.[153]

The church experienced its "golden age" from 1966 to 1972, when it had a strong media presence.[154] In February 1967, LaVey held a much publicized Satanic wedding, which was followed by the Satanic baptism of his daughter Zeena in May, and then a Satanic funeral in December.[155] Another publicity-attracting event was the "Topless Witch Revue", a nightclub show held on San Francisco's North Beach; the use of topless women to attract attention alienated a number of the church's early members.[156] Through these and other activities, he soon attracted international media attention, being dubbed "the Black Pope".[157] He also attracted a number of celebrities to join his Church, most notably Sammy Davis Junior and Jayne Mansfield.[158] LaVey also established branches of the church, known as grottos, in various parts of the United States.[159] He may have chosen the term grotto over coven because the latter term had come to be used by practitioners of the modern Pagan religion of Wicca.[160] These included the Babylon Grotto in Detroit, the Stygian Grotto in Dayton, and the Lilith Grotto in New York City.[161] In 1971, a Dutch follower of LaVey's, Maarten Lamers, established his own Kerk van Satan grotto in Amsterdam.[162]

As a result of the success of the film Rosemary's Baby and the concomitant growth of interest in Satanism, an editor at Avon Books, Peter Mayer, approached LaVey and commissioned him to write a book, which became The Satanic Bible.[163] While part of the text was LaVey's original writing, other sections of the book consisted of direct quotations from Arthur Desmond's right-wing tract Might is Right and the occultist Aleister Crowley's version of John Dee's Enochian Keys.[164] There is evidence that LaVey was inspired by the writings of the American philosopher Ayn Rand; and while accusations that he plagiarized her work in The Satanic Bible have been denied by one author, [165] Chris Mathews stated that "LaVey stole selectively and edited lightly" and that his "Satanism at times closely parallels Ayn Rand's Objectivist philosophy."[166] The book The Satanic Bible served to present LaVey's ideas to a far wider audience than they had previously had.[167] In 1972, he published a sequel, The Satanic Rituals.[168]

LaVey's Church emerged at a point in American history when Christianity was on the decline as many of the nation's youth broke away from their parental faith and explored alternative systems of religiosity.[168] The milieu in which LaVey's Church was operating was dominated by the counterculture of the 1960s; his Church reflected some of its concerns – free love, alternative religions, freedom from church and state – but ran contrary to some of the counterculture's other main themes, such as peace and love, compassion, and the use of mind-altering drugs.[169] He expressed condemnation of the hippies; in one ritual he hung an image of Timothy Leary upside down while stamping on a tablet of LSD.[170]

Later development: 1972–present

LaVey ceased conducting group rituals and workshops in his home in 1972.[171] In 1973, church leaders in Michigan, Ohio, and Florida split to form their own Church of Satanic Brotherhood, however this disbanded in 1974 when one of its founders publicly converted to Christianity.[172] Subsequently, Church members based in Kentucky and Indiana left to found the Ordo Templi Satanis.[172] In 1975, LaVey disbanded all grottos, leaving the organisation as a membership-based group that existed largely on paper.[173] He claimed that this had been necessary because the grottos had come to be dominated by social misfits who had not benefitted the church as a whole.[152] In a private letter, he expressed frustration that despite growing church membership, "brain surgeons and Congressmen are still in short supply".[174] He also announced that thenceforth all higher degrees in the church would be awarded in exchange for contributions of cash, real estate, or valuable art.[175] Dissatisfied with these actions, in 1975, the high-ranking Church member Michael Aquino left to found his own Satanic organisation, the Temple of Set,[176] which differed from LaVey's Church by adopting a belief that Satan literally existed.[51] According to Lap, from this point on Satanism became a "splintered and disorganized movement".[6]

Between the abolition of the grotto system in 1975 and the establishment of the internet in the mid-1990s, The Satanic Bible remained the primary means of propagating Satanism.[11] During this period, a decentralized, anarchistic movement of Satanists developed that was shaped by many of the central themes that had pervaded LaVey's thought and which was expressed in The Satanic Bible.[37] Lewis argued that in this community, The Satanic Bible served as a "quasi-scripture" because these independent Satanists were able to adopt certain ideas from the book while merging them with ideas and practices drawn from elsewhere.[37]

During the late 1980s, LaVey returned to the limelight, giving media interviews, attracting further celebrities, and reinstating the grotto system.[152] In 1984 he separated from his wife, Diane Hegarty, and began a relationship with Blanche Barton,[177] who was his personal assistant.[178] In 1988 Hegarty brought a court case against LaVey, claiming that he she owned half of the church and LaVey's Black House. The court found in Hegarty's favour, after which LaVey immediately declared bankruptcy.[179] In May 1992, the ex-couple reached a settlement. The Black House was sold to a wealthy friend, the property developer Donald Werby, who agreed to allow LaVey to continue living at the residence for free.[180] Also in 1992, LaVey published his first book in twenty years, The Devil's Notebook.[152] This was followed by the posthumous Satan Speaks in 1998, which included a foreword from the rock singer Marilyn Manson,[181] who was a priest in the church.[182]

In his final years, LaVey suffered from a heart condition, displayed increasing paranoia, and died in October 1997.[183] In November, the church announced that it would subsequently be run by two High Priestesses of joint rank, Barton and LaVey's daughter Karla LaVey.[184] That same year, the church established an official website.[185] Barton attempted to purchase the Black House from Werby, but was unable to raise sufficient funds; the building had fallen into disrepair and was demolished in 2001, subsequently being replaced with an apartment block.[186] A disagreement subsequently emerged between Barton and Karla, resulting in an agreement that Barton would retain legal ownership of the name and organization of the church while LaVey's personal belongings and copyrights would be distributed among his three children, Karla, Zeena, and Satan Xerxes.[187] Barton stood down as High Priestess in 2002, although continued to chair the church's Council of Nine.[188] The headquarters of the church were then moved from San Francisco to New York, where Peter H. Gilmore was appointed the church's High Priest, and his wife Peggy Nadramia as its High Priestess.[188]

After LaVey's death, conflict over the nature of Satanism intensified within the Satanic community.[189] At Halloween 1999 Karla established the First Satanic Church, which uses its website to promote the idea that it represents a direct continuation of the original Church of Satan as founded by Anton LaVey.[190] Other LaVeyan groups appeared elsewhere in the United States. An early member of the Church of Satan, John Dewey Allee, established his own First Church of Satan, claiming allegiance to LaVey's original teachings and professing that LaVey himself had deviated from them in later life.[191] In 1986, Paul Douglas Valentine founded the New York City-based World Church of Satanic Liberation, having recruited many of its members through Herman Slater's Magickal Childe esoteric store. Its membership remained small and it was discontinued in 2011.[188] In 1991, the Embassy of Lucifer was established by the Canadian Tsirk Susuej, which was influenced by LaVeyan teachings but held that Satan was a real entity.[192] Splinter groups from Susuej's organisation included the Embassy of Satan in Stewart, British Columbia, and the Luciferian Light Group in Baltimore.[192]

LaVeyan groups also cropped up elsewhere in the world, with a particular concentration in Scandinavia; most of these Scandinavian groups either split from the Church of Satan or never affiliated with it.[193] These included the Svenska Satanistkyrkan and the Det Norske Sataniske Samfunn,[193] as well as the Prometheus Grotten of the Church of Satan which was established in Denmark in 1997 but which officially seceded in 2000.[193] A Satanic Church was also established in Estonia based on the LaVeyan model; it later renamed itself the Order of the Black Widow.[194]

The Church of Satan became increasingly doctrinally-rigid and focused on maintaining the purity of LaVeyan Satanism.[195] The church's increased emphasis on their role as the bearer of LaVey's legacy was partly a response to the growth in non-LaVeyan Satanists.[148] Some Church members – including Gilmore[185] – claimed that only they were the "real" Satanists and that those belonging to different Satanic traditions were "pseudo" Satanists.[195] After examining many of these claims on the church's website, Lewis concluded that it was "obsessed with shoring up its own legitimacy by attacking the heretics, especially those who criticize LaVey".[172] Meanwhile, the church experienced an exodus of its membership in the 2000s, with many of these individuals establishing new groups online.[189] Although the church's public face had performed little ceremonial activity since the early 1970s, in June 2006 they held a Satanic 'High Mass' in Los Angeles to mark the church's fortieth birthday.[196]

Demographics

Membership levels of the Church of Satan are hard to determine, as the organisation has not released such information.[197] During its early years, the church claimed a membership of around 10,000, although defectors subsequently claimed that the number was only in the hundreds.[160] Membership was largely, although not exclusively, white.[198] LaVey recognised this, suggesting that the church appealed particularly to white Americans because they lacked the strong sense of ethnic identity displayed by African-Americans and Hispanic Americans.[199] The historian of religion Massimo Introvigne suggested that it had never had more than 1000 or 2000 members at its height, but that LaVeyan ideas had had a far greater influence through LaVey's books.[200] Membership is gained by paying $225 and filling out a registration statement,[35] and thus initiates are bestowed with lifetime memberships and not charged annual fees.[152]

La Fontaine thought it likely that the easy availability of LaVey's writings would have encouraged the creation of various Satanic groups that were independent of the Church of Satan itself.[117] In The Black Flame, a number of groups affiliated with the church has been mentioned, most of which are based in the United States and Canada although two groups were cited as having existed in New Zealand.[117] In his 2001 examination of Satanists, the sociologist James R. Lewis noted that, to his surprise, his findings "consistently pointed to the centrality of LaVey's influence on modern Satanism".[201] "Reflecting the dominant influence of Anton LaVey's thought", Lewis noted that the majority of those whom he examined were atheists or agnostics, with 60% of respondents viewing Satanism as a symbol rather than a real entity.[202] 20% of his respondents described The Satanic Bible as the most important factor that attracted them to Satanism.[203] Elsewhere, Lewis noted that few Satanists who weren't members of the Church of Satan would regard themselves as "orthodox LaVeyans".[11]

Examining the number of LaVeyan Satanists in Britain, in 1995 the religious studies scholar Graham Harvey noted that the Church of Satan had no organized presence in the country.[33] He noted that LaVey's writings were widely accessible in British bookshops,[33] and La Fontaine suggested that there may have been individual Church members within the country.[117]

See also

- Contemporary Religious Satanism

- Satanic ritual abuse – Widespread moral panic alleging abuse in the context of occult rituals

- Devil in popular culture

- Conceptions of God

- Nontheistic religion – Religious thought and practice independent of belief in deities.

- Religious naturalism – History and overview of religious naturalism

- Secular religion – Communal belief system that often rejects or neglects the supernatural

References

Notes

- Lap 2013, p. 83; Dyrendal 2013, p. 124.

- Petersen 2009, p. 224; Dyrendal 2013, p. 123.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 81.

- Dyrendal 2012, p. 370; Petersen 2012, p. 95.

- Harvey 1995, p. 290; Partridge 2004, p. 82; Petersen 2009, pp. 224–225; Schipper 2010, p. 108; Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 79.

- Lap 2013, p. 84.

- Petersen 2005, p. 424.

- Gallagher 2006, p. 165.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 96.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 70.

- Lewis 2002, p. 2.

- Gardell 2003, p. 288.

- Drury 2003, p. 188.

- Taub & Nelson 1993, p. 528.

- Ohlheiser, Abby (7 November 2014). "The Church of Satan wants you to stop calling these 'devil worshiping' alleged murderers Satanists". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 99.

- Contemporary Religious Satanism: A Critical Anthology & Petersen 2009, p. 9.

- The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity & Faxneld, Petersen 2013, p. 129.

- Satanism Today & Lewis 2001, p. 330.

- Lap 2013, p. 85.

- Lewis 2002, pp. 2, 13.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 317.

- Lewis 2003, p. 117.

- The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity & Faxneld, Petersen 2013, p. 115.

- Petersen 2012, p. 114.

- Lewis 2003, p. 116.

- Lewis 2003, p. 105.

- Lewis 2002, p. 12.

- Petersen 2013, p. 232.

- Bromley 2005, pp. 8127–8128.

- Gallagher 2005, p. 6530.

- Robinson, Eugene (7 September 2016). "My Dinner With The Devil". OZY. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- Harvey 1995, p. 290.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 97.

- Petersen 2005, p. 430.

- Lewis 2002, p. 4; Petersen 2005, p. 434.

- Lewis 2002, p. 4.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 336.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 328.

- Maxwell-Stuart 2011, p. 198.

- Harvey 1995, p. 291.

- Harvey 1995, p. 290; La Fontaine 1999, p. 97.

- Lewis 2001a, p. 17; Gallagher 2006, p. 165.

- Schipper 2010, p. 107.

- Schipper 2010, p. 106.

- Cavaglion & Sela-Shayovitz 2005, p. 255.

- Wright 1993, p. 143.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287; Muzzatti 2005, p. 874.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 348.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 355.

- Schipper 2010, p. 109.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 80.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 50.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 326.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 374.

- Gardell 2003, p. 289; van Luijk 2016, p. 366.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 97; Lap 2013, p. 95; van Luijk 2016, p. 367.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287; Petersen 2005, p. 447; Lap 2013, p. 95.

- Lewis 2001a, p. 18; Lewis 2002, p. 9.

- Dyrendal 2012, p. 370.

- Lewis 2002, p. 4; Gardell 2003, p. 288; Baddeley 2010, p. 74; Lap 2013, p. 94.

- Lap 2013, p. 94.

- Lap 2013, p. 95.

- Gardell 2003, p. 289.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 322.

- Dyrendal 2013, p. 129.

- Lap 2013, p. 92.

- Gardell 2003, p. 288; Schipper 2010, p. 107.

- Gardell 2003, p. 288; Lap 2013, p. 91; Faxneld & Petersen 2014, p. 168; van Luijk 2016, p. 321.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2014, p. 168.

- Lap 2013, p. 91.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2014, p. 169.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2014, p. 170.

- Gardell 2003, p. 288; Maxwell-Stuart 2011, p. 198.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 357.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 379.

- Lap 2013, p. 95; van Luijk 2016, p. 376.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 376.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 375.

- Lewis 2002, pp. 3–4; van Luijk 2016, p. 336.

- Lewis 2002, pp. 3–4.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 288–289; Petersen 2012, p. 95; Lap 2013, p. 96; van Luijk 2016, p. 342.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 342.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 339.

- Lewis 2002, p. 4; van Luijk 2016, p. 339.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 337.

- Dyrendal 2012, p. 376.

- Gardell 2003, p. 289; Dyrendal 2012, p. 377; Dyrendal, Petersen & Lewis 2016, p. 86.

- Dyrendal 2012, p. 377.

- van Luijk 2016, pp. 336–337.

- Gardell 2003, p. 289; Petersen 2012, pp. 95–96; Lap 2013, p. 97; Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 86.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 86.

- The Invention of Satanism Dyrendal, Petersen 2016, p. 89.

- Lap 2013, p. 98.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 98.

- Medway 2001, p. 21.

- La Fontaine 1999, pp. 98–99.

- Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 6: The Twentieth Century & Blecourt, Hutton, Fontaine 1999, p. 91.

- Controversial New Religions & Lewis, Petersen, p. 418.

- The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity & Faxneld, Petersen 2013, p. 97.

- Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science & Lewis, Hammer 2014, p. 90.

- Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science & Petersen 2010, p. 67.

- Sexuality and New Religious Movements & Lewis, Bogdan 2014.

- Controversial New Religions & Lewis, Petersen 2014, p. 418.

- Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science & Lewis, Hammer 2010, p. 89.

- Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science & Lewis, Hammer 2010, p. 68.

- Petersen 2005, p. 431.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 192.

- Petersen 2011, pp. 159-160.

- Drury 2003, pp. 191–192; Baddeley 2010, p. 71; Van Luijk 2016, p. 297.

- Drury 2003, pp. 192–193.

- "The Eleven Satanic Rules of the Earth". Church of Satan. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Catherine Beyer. "The Nine Satanic Sins". Learn Religions. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 98; Lap 2013, p. 97.

- Faxneld 2013, p. 88.

- La Fontaine 1999, pp. 97, 98.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 100.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 97; van Luijk 2016, p. 337.

- La Fontaine 1999, p. 97; van Luijk 2016, p. 338.

- Petersen 2012, pp. 96–97; Faxneld 2013, p. 76; Lap 2013, p. 98.

- Faxneld 2013, p. 86.

- Petersen 2012, pp. 106–107.

- Petersen 2012, p. 106.

- "F.A.Q. Holidays". Church of Satan. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- LaVey, Anton Szandor (1969). "Religious Holidays". The Satanic Bible. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-01539-9. OCLC 26042819.

- The Dictionary of Cults, Sects, Religions and the Occult by Mather & Nichols, (Zondervan, 1993), P. 244, quoted at ReligiousTolerance.

- Medway 2001, p. 26.

- Lewis 2002, p. 20.

- Medway 2001, p. 26; Lewis 2001b, p. 20.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 20.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 21.

- Partridge 2005, p. 376.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 20; Partridge 2005, p. 376.

- Faxneld 2013, p. 75.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 299.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 297.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 295.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 51; Introvigne 2016, p. 300.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 51.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 301.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 300–301.

- van Luijk 2016, pp. 294, 296.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 296.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 52.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 52; van Luijk 2016, p. 296.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 53.

- Lewis 2002, p. 5; Gardell 2003, p. 285; Baddeley 2010, p. 71; Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 52.

- Lewis 2002, p. 5.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 346.

- Petersen 2005, p. 428; Baddeley 2010, pp. 66, 71; Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 53.

- Drury 2003, p. 197.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287.

- Faxneld & Petersen 2013, p. 79.

- Petersen 2013, p. 136.

- Petersen 2005, p. 438; Baddeley 2010, p. 71; Introvigne 2016, p. 309; van Luijk 2016, p. 297.

- Dyrendal, Lewis & Petersen 2016, p. 54; van Luijk 2016, p. 346.

- Baddeley 2010, p. 71.

- Gardell 2003, p. 286; Baddeley 2010, p. 72; Schipper 2010, pp. 105–106.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287; Baddeley 2010, p. 74.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 344.

- Baddeley 2010, p. 74.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 519; van Luijk 2016, pp. 344–345.

- Lewis 2002, p. 8; Baddeley 2010, p. 72.

- Lewis 2002, p. 8; Introvigne 2016, p. 315.

- Lewis 2002, p. 9.

- Mathews 2009, p. 65-66.

- Baddeley 2010, p. 72.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 298.

- Gardell 2003, p. 295; van Luijk 2016, p. 298.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 299.

- Lap 2013, p. 84; van Luijk 2016, p. 345.

- Lewis 2002, p. 7.

- Lewis 2002, p. 7; Lap 2013, p. 84; Introvigne 2016, p. 518.

- van Luijk 2016, pp. 346–347.

- Drury 2003, p. 193; van Luijk 2016, p. 347.

- Drury 2003, pp. 193–194; Gallagher 2006, p. 160; Schipper 2010, p. 105.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 512–513.

- Lewis 2001b, p. 51.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 516; van Luijk 2016, pp. 377–378.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 516; van Luijk 2016, p. 378.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287; Introvigne 2016, p. 516.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 384.

- Introvigne 2016; van Luijk 2016, p. 516.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 516.

- Petersen 2013, p. 140.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 516; van Luijk 2016, p. 380.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287; Introvigne 2016, pp. 516–517.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 517.

- Petersen 2013, p. 139.

- Gallagher 2006, p. 162; van Luijk 2016, p. 380.

- Gallagher 2006, p. 162.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 518.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 520.

- Introvigne 2016, pp. 519–520.

- Lewis 2002, p. 5; van Luijk 2016, p. 380.

- Petersen 2012, pp. 115–116.

- Gardell 2003, p. 287; Petersen 2005, p. 430.

- van Luijk 2016, pp. 369–370.

- van Luijk 2016, p. 370.

- Introvigne 2016, p. 320.

- Lewis 2001a, p. 5.

- Lewis 2001a, p. 11.

- Lewis 2001a, p. 15.

Sources

- Alfred, A. "The Church of Satan". In C. Glock; R. Bellah (eds.). The New Religious Consciousness. Berkeley. pp. 180–202.

- Baddeley, Gavin (2010). Lucifer Rising: Sin, Devil Worship & Rock n' Roll (third ed.). London: Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-455-5.

- Bromley, David G. (2005). "Satanism". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. 12 (2 ed.). Detroit, IL: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Cavaglion, Gabriel; Sela-Shayovitz, Revital (2005). "The Cultural Construction of Contemporary Satanic Legends in Israel". Folklore. 116 (3): 255–271. doi:10.1080/00155870500282701. S2CID 161360139.

- Drury, Nevill (2003). Magic and Witchcraft: From Shamanism to the Technopagans. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500511404.

- Dyrendal, Asbjørn (2012). "Satan and the Beast: The Influence of Aleister Crowley on Modern Satanism". In Bogdan, Henrik; Starr, Martin P. (eds.). Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 369–394. ISBN 978-0-19-986309-9.

- ——— (2013). "Hidden Persuaders and Invisible Wars: Anton LaVey and Conspiracy Culture". In Per Faxneld; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 123–40. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- Dyrendal, Asbjørn; Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aa. (2016). The Invention of Satanism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195181104.

- Faxneld, Per (2013). "Secret Lineages and de facto Satanists: Anton LaVey's Use of Esoteric Tradition". In Egil Asprem; Kennet Granholm (eds.). Contemporary Esotericism. Sheffield: Equinox. pp. 72–90. ISBN 978-1-908049-32-2.

- Faxneld, Per; Petersen, Jesper Aa. (2013). "The Black Pope and the Church of Satan". In Per Faxneld; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- ——— ——— (2014). "Cult of Carnality: Sexuality, Eroticism, and Gender in Contemporary Satanism". In Henrik Bogdan; James R. Lewis (eds.). Sexuality and New Religious Movements. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 165–181. ISBN 978-1137409621.

- Gallagher, Eugene V. (2005). "New Religious Movements: Scriptures of New Religious Movements". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. 12 (2 ed.). Detroit, IL: Macmillan Reference USA.

- Gallagher, Eugene (2006). "Satanism and the Church of Satan". In Eugene V. Gallagher; W. Michael Ashcraft (eds.). Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America. Greenwood. pp. 151–168. ISBN 978-0313050787.

- Gardell, Matthias (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3071-4.

- Harvey, Graham (1995). "Satanism in Britain Today". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 10 (3): 283–296. doi:10.1080/13537909508580747.

- Introvigne, Massimo (2016). Satanism: A Social History. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004288287.

- La Fontaine, Jean (1999). "Satanism and Satanic Mythology". In Bengt Ankarloo; Stuart Clark (eds.). The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe Volume 6: The Twentieth Century. London: Athlone. pp. 94–140. ISBN 0 485 89006 2.

- Lap, Amina Olander (2013). "Categorizing Modern Satanism: An Analysis of LaVey's Early Writings". In Per Faxneld; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). The Devil's Party: Satanism in Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–102. ISBN 978-0-19-977924-6.

- Lewis, James L. (2001a). "Who Serves Satan? A Demographic and Ideological Profile" (PDF). Marburg Journal of Religion. 6 (2): 1–25.

- ——— (2001b). Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion, Folklore, and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1576072929.

- ——— (2002). "Diabolical Authority: Anton LaVey, The Satanic Bible and the Satanist "Tradition"" (PDF). Marburg Journal of Religion. 7 (1): 1–16.

- ——— (2003). Legitimating New Religions. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3534-0.

- Mathews, Chris (2009). Modern Satanism: Anatomy of a Radical Subculture. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0313366390.

- Maxwell-Stuart, P. G. (2011). Satan: A Biography. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-0575-3.

- Medway, Gareth J. (2001). Lure of the Sinister: The Unnatural History of Satanism. New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814756454.

- Muzzatti, Stephen L. (2005). "Satanism". In Mary Bosworth (ed.). Encyclopedia of Prisons and Correctional Facilities. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Reference. pp. 874–876. ISBN 978-1-4129-2535-8.

- Partridge, Christopher (2004). The Re-Enchantment of the West Volume. 1: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture, and Occulture. London: T&T Clark International. ISBN 978-0567084088.

- ——— (2005). The Re-Enchantment of the West, Volume 2: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture and Occulture. London: T&T Clark.

- Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2005). "Modern Satanism: Dark Doctrines and Black Flames". In James R. Lewis; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). Controversial New Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 423–457. ISBN 978-0195156836.

- ——— (2009). "Satanists and Nuts: The Role of Schisms in Modern Satanism". In James R. Lewis; Sarah M. Lewis (eds.). Sacred Schisms: How Religions Divide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 218–247. ISBN 978-0521881470.

- ——— (2010). ""We Demand Bedrock Knowledge": Modern Satanism Between Secularized Esotericism and 'Esotericized' Secularism". In James R. Lewis; Olav Hammer (eds.). Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science. Leiden: Brill. pp. 67–114. ISBN 978-9004187917.

- ——— (2011). Between Darwin and the Devil: Modern Satanism as Discourse, Milieu and Self (PDF) (Doctoral thesis). Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ——— (2012). "The Seeds of Satan: Conceptions of Magic in Contemporary Satanism". Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism. 12 (1): 91–129. doi:10.1163/147783512X614849.

- ——— (2013). "From Book to Bit: Enacting Satanism Online". In Egil Asprem; Kennet Granholm (eds.). Contemporary Esotericism. Durham: Acumen. pp. 134–158. ISBN 978-1-908049-32-2.

- ——— (2014). "Carnal, Chthonian, Complicated: The Matter of Modern Satanism". In James R. Lewis; Jesper Aagaard Petersen (eds.). Controversial New Religions (second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 399–434. ISBN 978-0199315314.

- Schipper, Bernd U. (2010). "From Milton to Modern Satanism: The History of the Devil and the Dynamics between Religion and Literature". Journal of Religion in Europe. 3 (1): 103–124. doi:10.1163/187489210X12597396698744.

- Taub, Diane E.; Nelson, Lawrence D. (August 1993). "Satanism in Contemporary America: Establishment or Underground?". The Sociological Quarterly. 34 (3): 523–541. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1993.tb00124.x.

- van Luijk, Ruben (2016). Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190275105.

- Wright, Lawrence (1993). Saints & Sinners. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-57924-0.

External links

- Official Church of Satan website

- “Satanism as Weltanschauung”, the philosophy of the Church of Satan (presented by Kevin I. Slaughter at the Maryland Institute College of Art)

- "Satan as Rebel Hero: Henry M. Tichenor and the Radical Anti-religious (presented by Kevin I. Slaughter and Robert Merciless at SkeptiCamp DC on October 3, 2010, College Park, MD)

- "What Does Satanism Mean to You?" (Interview with members of the Church of Satan)

- "Inside the Church of Satan (Documentary)

- 9sense Podcast interview with Peter H. Gilmore on Walpurgisnacht.

Satanism: An interview with Church of Satan High Priest Peter Gilmore at Wikinews

Satanism: An interview with Church of Satan High Priest Peter Gilmore at Wikinews