Lake Lotawana, Missouri

Lake Lotawana is a city in Jackson County, Missouri, United States and is located 35 miles southeast of downtown Kansas City bordering Blue Springs and Lee’s Summit. The population was 1,939 as of the 2010 census. It is part of the Kansas City metropolitan area.[7]

Lake Lotawana, Missouri | |

|---|---|

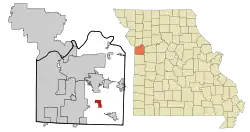

Location of Lake Lotawana, Missouri | |

| Coordinates: 38°55′36″N 94°15′12″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Jackson |

| Incorporated | 1958[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Board of Alderman |

| • Mayor | Tracy Rasmussen |

| • City Administrator | Nick Shigouri |

| • City Planner | Lindsey Jorgensen |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.30 sq mi (29.26 km2) |

| • Land | 10.31 sq mi (26.71 km2) |

| • Water | 0.98 sq mi (2.55 km2) |

| Elevation | 896 ft (273 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,939 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 2,109 |

| • Density | 204.48/sq mi (78.95/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 64064, 64086, 64029, 64070 |

| Area code(s) | 816 |

| FIPS code | 29-39980[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0720753[6] |

| Website | www |

The city derives its name from the lake that takes up most of the city, which is said to be named after an Indian princess.[8]

History

Lake Lotawana was conceived, purchased, built and developed by Milton Thompson, owner of nearby Highland Farms, the world's largest Hereford cattle breeding farm at that time (1927).[9] He had previously developed nearby Lake Tapawingo, a lake community with retreats for wealthy Kansas City businessmen. Permission for the new lake was requested November 7, 1927 and surveying was completed June 13, 1928. The dam was completed in the fall of 1929 just before the stock market crash that ushered in the Great Depression. An extended drought meant the lake did not fill completely until the Spring of 1935. Early land sales were slow due to the Depression.

Lake Lotawana was named after a fabled Native American princess whose name meant "sparkling water". The legend of Princess Lotawana tells of her life in the Catskill Mountains of New York. In her legend, she was murdered on her wedding day by a jealous spurned suitor.

The area of Sni-A-Bar creek that later became Lake Lotawana was used as a hideout and staging area by Quantrill's Raiders during the Civil War. This band of irregulars conducted raids against Union Army units and pro-Union and Abolitionist residents of Missouri and Kansas. There are accounts that they engaged in the Battle of Quantrill's Cove on August 13, 1862, where they defeated a Union Cavalry force under Major Emory L. Foster. Accounts of the incident are not clear, but this engagement was a spillover from the Battle of Lone Jack. This battle was supposed to have taken place near present-day Quantrill's Cove, near the west end of the lake. Quantrill's group also staged the famous and better known raid against Lawrence, Kansas, known as the Lawrence massacre on August 21, 1863. The brutality of the raid resulted in the Order No. 11 by Union Brigadier General Thomas C. Ewing, garrisoned in present-day Kansas City. This order resulted in the forced relocation of all Confederate sympathizers in four counties, including the area of present-day Lake Lotawana. It was meant to clear the counties of a civilian support structure, and resulted in much property loss by the residents of the area. Most homes were burnt to the ground and people had to leave with little more than the clothes on their backs and what they could load into a wagon. The band of Quantrill's Raiders continued their efforts to harass the Union forces after the order was implemented. There were rumors that stolen property from the raid on Lawrence was buried by Quantrill's men in or near the Sni-a-Bar creek valley that later became Lake Lotawana. Treasure Cove in the A Block of the lake was named in reference to the buried treasure.

After the Civil War, settlers returned to the area, mostly developing the surrounding area as farms. Sni-A-Bar creek remained a heavily timbered valley, not as suitable for crops or livestock. There was a sulphur spring in block T inside Gate 3 that was a site of picnics and revivals. Most famously, the Baptist Minister Joab Powell of the Union Church (near the modern day intersection of 7 and 50 highways) would hold revivals in what is now called Waterfall Cove. The church was destroyed by a cyclone in 1894.

Milton Thompson purchased much of the land, employing Oliver Sheley to survey the lake. He later resided at C-23 until his death in 1967. Originally, the lake had locked gates, with guards stationed to check for passes. Many of the original homes were cabins, made of logs, meant for summer vacation dwellings only. A mixture of summer cabins and permanent dwellings were built through the 1930s. The dam required many repairs and upgrades through the 1930s and 1940s, including the first WPA project in Jackson County, Missouri.

Geography

Lake Lotawana is located at 38°55′36″N 94°15′12″W (38.926627, −94.253201).[10]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the City has a total area of 11.29 square miles (29.24 km2), of which 10.31 square miles (26.70 km2) is land and 0.98 square miles (2.54 km2) is water.[11]

According to the Lake Lotawana website[12] the lake has 600 acres of surface water and 27 miles of shoreline.

The City originally had approximately 2.3 square miles of area. Two annexations in 2001 and 2004, respectively, expanded the City's boundary south beyond U.S. Highway 50. This included the 2200 acre Barber property, and the Foxberry and Oak Haven subdivisions. The City presently encompasses roughly 11.3 square miles.

Government

Early organization of the area was managed by the Lake Lotawana Development Company.[9] The city was incorporated into a fourth class city on November 24, 1958 in order to avoid being annexed into rapidly growing Lee's Summit and Blue Springs.The new City of Lake Lotawana Government established in 1958 is operated by the Elected Mayor, the Elected Board of Aldermen, City Administrator and Police Department. The lake and common areas themselves are owned by the non-profit Lake Lotawana Association.[13] Lake Lotawana is served by the Lotawana Fire Protection District, but some residents are covered by Prairie Township Fire Protection District and the Lone Jack Fire Department. Residents are members of the Lee's Summit R7 School district, and students attend Mason Elementary, Bernard C. Campbell Middle School, and Lee's Summit North High School.[14] Water is supplied by Public Water Supply Districts 13 and 15.

The Mayor, Aldermen, and City Collector are elected for 2 year terms.[15] The 6 Aldermen are elected 3 at a time in staggered terms. The Mayor presides over the Board of Aldermen, but does not vote on resolutions or ordinances unless it is a tie vote.

A Comprehensive Plan was completed in 2017 and is available on the City's website.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1960 | 1,499 | — | |

| 1970 | 1,786 | 19.1% | |

| 1980 | 1,875 | 5.0% | |

| 1990 | 2,141 | 14.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,872 | −12.6% | |

| 2010 | 1,939 | 3.6% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 2,109 | [4] | 8.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 1,939 people, 840 households, and 566 families residing in the city. The population density was 188.1 inhabitants per square mile (72.6/km2). There were 1,299 housing units at an average density of 126.0 per square mile (48.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 96.8% White, 0.4% African American, 0.3% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.4% from other races, and 1.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.8% of the population.

There were 840 households, of which 26.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.6% were married couples living together, 5.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 32.6% were non-families. 24.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.75.

The median age in the city was 46.7 years. 19.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 22.8% were from 25 to 44; 37.9% were from 45 to 64; and 14.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 51.7% male and 48.3% female.

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 1,872 people, 815 households, and 567 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,230.3 people per square mile (475.5/km2). There were 970 housing units at an average density of 637.5 per square mile (246.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.86% White, 0.21% African American, 0.59% Native American, 0.16% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, and 1.12% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.34% of the population.

There were 815 households, out of which 26.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.4% were married couples living together, 5.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.4% were non-families. 24.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.71.

In the city the population was spread out, with 19.6% under the age of 18, 4.8% from 18 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 34.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 44 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 103.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $65,750, and the median income for a family was $72,500. Males had a median income of $50,991 versus $35,774 for females. The per capita income for the city was $38,125. About 2.8% of families and 4.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.3% of those under age 18 and 2.5% of those age 65 or over.

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-06-10. Retrieved 2016-05-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- https://www.marc.org/Data-Economy/Metrodataline/General-Information/Statistical-Areas

- "Jackson County Place Names, 1928–1945 (archived)". The State Historical Society of Missouri. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Stalling, Francis Genevieve (1986). Lake Lotawana, the "Promised Land". Blue Springs, Missouri: Blue Springs Examiner. pp. multiple.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "About Lake Lotawana". City of Lake Lotawana. 2018-12-16.

- "The Lotawana Association".

- "City of Lake Lotawana Links and Contacts".

- "Lake Lotawana Municipal Code, Article 1".

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.