Land-grant university

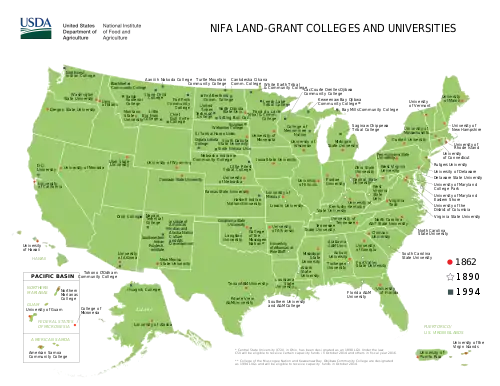

A land-grant university (also called land-grant college or land-grant institution) is an institution of higher education in the United States designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890.[1]

| Education in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

Signed by Abraham Lincoln, the first Morrill Act began to fund educational institutions by granting federally controlled land to the states for them to sell, to raise funds, to establish and endow "land-grant" colleges. The mission of these institutions as set forth in the 1862 Act is to focus on the teaching of practical agriculture, science, military science, and engineering (though "without excluding... classical studies") as a response to the industrial revolution and changing social class.[2][3] This mission was in contrast to the historic practice of higher education to focus on a liberal arts curriculum. A 1994 expansion gave land-grant status to several tribal colleges and universities.[4]

Ultimately, most land-grant colleges became large public universities that today offer a full spectrum of educational opportunities. However, some land-grant colleges are private schools, including Cornell University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Tuskegee University.[5]

History

The concept of publicly funded agricultural and technical educational institutions first rose to national attention through the efforts of Jonathan Baldwin Turner in the late 1840s.[6] The first land-grant bill was introduced in Congress by Representative Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont in 1857.[6] The bill passed in 1859, but was vetoed by President James Buchanan.[6] Morrill resubmitted his bill in 1861, and President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act into law in 1862.[7] The law gave every state and territory 30,000 acres per member of Congress to be used in establishing a "land grant" university. Over 17 million acres, mostly taken from Indigenous peoples through violence-backed land cessions, were granted through the federal land-grant law.[8][9][10]

Upon passage of the federal land-grant law in 1862, Iowa was the first state legislature to accept the provisions of the Morrill Act, on September 11, 1862.[11][12] Iowa subsequently designated the State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University) as the land-grant college on March 29, 1864.[12][13] The first land-grant institution actually created under the Act was Kansas State University, which was established on February 16, 1863, and opened on September 2, 1863.[14] The oldest school that currently holds land-grant status is Rutgers University, founded in 1766 and designated the land-grant college of New Jersey in 1864. The oldest school to ever hold land-grant status was Yale University (founded in 1701), which was named Connecticut's land-grant recipient in 1863. This designation was later stripped by the Connecticut legislature in 1893 under populist pressure and transferred to what would become the University of Connecticut.[15]

A second Morrill Act was passed in 1890, aimed at the former Confederate states. This act required each state to show that race was not an admissions criterion, or else to designate a separate land-grant institution for persons of color.[16] Among the seventy colleges and universities which eventually evolved from the Morrill Acts are several of today's historically black colleges and universities. Though the 1890 Act granted cash instead of land, it granted colleges under that act the same legal standing as the 1862 Act colleges; hence the term "land-grant college" properly applies to both groups.

Later on, other colleges such as the University of the District of Columbia and the "1994 land-grant colleges" for Native Americans were also awarded cash by Congress in lieu of land to achieve "land-grant" status.

In imitation of the land-grant colleges' focus on agricultural and mechanical research, Congress later established programs of sea grant colleges (aquatic research, in 1966), space grant colleges (space research, in 1988), and sun grant colleges (sustainable energy research, in 2003).

West Virginia State University, a historically black university, is the only current land-grant university to have lost land-grant status (when desegregation cost it its state funding in 1957) and then subsequently regained it, which happened in 2001.

The land-grant college system has been seen as a major contributor in the faster growth rate of the US economy that led to its overtaking the United Kingdom as economic superpower, according to research by faculty from the State University of New York.[17]

The three-part mission of the land-grant university continues to evolve in the twenty-first century. What originally was described as "teaching, research, and service" was renamed "learning, discovery, and engagement" by the Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities, and again recast as "talent, innovation, and place" by the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities (APLU).[18]

State law precedents

Prior to the enactment of the Morrill Act in 1862, individual states established institutions of higher education with grants of land. The first state to do so was Georgia, which set aside 40,000 acres for higher education in 1784 and incorporated the University of Georgia in 1785.[19]

Michigan State University was chartered under Michigan state law as a state agricultural land-grant institution on February 12, 1855, as the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan, receiving an appropriation of 14,000 acres (57 km2) of state-owned land.[20] The Farmers' High School of Pennsylvania (later to become The Pennsylvania State University) followed as a state agricultural land-grant school on February 22 of that year.[21] Michigan State and Penn State were subsequently designated as the federal land-grant colleges for their states in 1863. In 1955, the U.S. Postal service issued a commemorative stamp to celebrate the two institutions as "first of the land-grant type institutions to be founded."[22]

Hatch Act and Smith–Lever Act

The mission of the land-grant universities was expanded by the Hatch Act of 1887, which provided federal funds to states to establish a series of agricultural experiment stations under the direction of each state's land-grant college, as well as pass along new information, especially in the areas of soil minerals and plant growth. The outreach mission was further expanded by the Smith–Lever Act of 1914 to include cooperative extension—the sending of agents into rural areas to help bring the results of agricultural research to the end users. Beyond the original land grants, each land-grant college receives annual federal appropriations for research and extension work on the condition that those funds are matched by state funds.

Expansion

While today's land-grant universities were initially known as land-grant colleges, only a few of the more than 70 institutions that developed from the Morrill Acts retain "College" in their official names; most are universities.

The University of the District of Columbia received land-grant status in 1967 and a $7.24 million endowment (USD) in lieu of a land grant. In a 1972 Special Education Amendment, American Samoa, Guam, Micronesia, Northern Marianas, and the Virgin Islands each received $3 million.

In 1994, 29 tribal colleges and universities became land-grant institutions under the Improving America's Schools Act of 1994. As of 2008, 32 tribal colleges and universities have land-grant status in the US. Most of these colleges grant two-year degrees. Six are four-year institutions, and two offer a master's degree.

Land acknowledgement statements

In the early 21st century, a growing number of land-grant universities placed land acknowledgement statements on their websites in recognition of the fact that their institutions occupy lands that were once home to Native Americans.[23][24] For example, the University of Illinois System states, "These lands were the traditional birthright of indigenous peoples who were forcibly removed and who have faced two centuries of struggle for survival and identity in the wake of dispossession. We hereby acknowledge the ground on which we stand so that all who come here know that we recognize our responsibilities to the peoples of that land and that we strive to address that history so that it guides our work in the present and the future."[25]

In an article in High Country News, Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone criticized these statements for failing to acknowledge the true breadth of the benefits derived from formerly Native American land. They pointed out that land grants were not only used for campus sites but also included many other parcels which were rented or sold to generate funds that formed the basis of many universities' endowments.[10] Lee and Ahtone also pointed out that only a few land-grant universities have undertaken significant efforts at reconciliation with respect to the latter types of parcels, such as identifying what portions of their current resources are traceable to Native American lands and reallocating some of those resources to help Native Americans.[10]

Nomenclature

Land-grant universities are not to be confused with sea grant colleges (a program instituted in 1966), space grant colleges (instituted in 1988), or sun grant colleges (instituted in 2003). In some states, the land-grant missions for agricultural research and extension have been relegated to a statewide agency of the university system rather than the original land-grant campus; an example is the Texas A&M University System, whose agricultural missions, including the agricultural college at the system's main campus, are now under the umbrella of Texas A&M AgriLife.

Relevant legislation

- The Morrill Act of 1862

- The Hatch Act of 1887

- The second Morrill Act of 1890

- The Adams Act – 1906

- The Nelson Act – 1907

- The Smith–Lever Act of 1914

- Chapter 79 – May 8, 1914

- The Smith–Hughes Act – 1917

- The Parnell Act – 1925

- The Capper–Ketcham Act – 1928

- The Bankhead–Jones Act of 1935

- The Bankhead–Flanagan Act – 1945

- The Research Marketing Act – 1946

- Amendment to Smith–Lever Act – 1953, 1955, 1961, 1962, 1968

- Amended Hatch Act – 1955

- The McIntire–Stennis Act – 1962

- The Research Facilities Act – 1965

- Public Law 89-106 – 1965

- The National Sea Grant College Program – 1966

- The Rural Development Act – 1972

- The Food and Agriculture Act of 1977

- The National Agricultural Research, Extension, and Teaching Policy Act of 1977 – Title XIV

- The Resource Extension Act – 1978

- Amendment to Title XIV – 1981

- The Agriculture and Food Act of 1981

- Amendment to Title XIV of Food Security Act – 1985

- Improving America's Schools Act of 1994—extended land-grant status to tribal colleges and universities

See also

References

- Collins, John Williams; O'Brien, Nancy P., eds. (2003). The Greenwood Dictionary of Education. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 227. ISBN 0-89774-860-3.

- 7 U.S.C. § 304

- What Is A Land-Grant College? (PDF), Washington State University, retrieved July 12, 2011

- Greenwood Dictionary of Education. 2003. p. 235.

- Brunner, Henry Sherman (1962). Land-grant Colleges and Universities, 1862-1962. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- The Land-Grant Tradition, NASULGC, 2008, p. 3, archived from the original on December 4, 2010, retrieved July 28, 2010

- Cross II, Coy F. (1997). Justin Smith Morrill: Father of the Land-Grant Colleges. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-508-2.

- Martin, Michael V. (February 18, 2018). "A Time for Substance: Confronting Funding Inequities at Land-Grant Institutions". Tribal College Journal. 29 (3). Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Nash, Margaret A. (November 2019). "Entangled Pasts: Land-Grant Colleges and American Indian Dispossession". History of Education Quarterly. 59 (4): 437–467. doi:10.1017/heq.2019.31.

- Lee, Robert; Ahtone, Tristan (March 30, 2020). "Land-Grab Universities". High Country News. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "History of Iowa State: Time Line, 1858–1874". Iowa State University. 2006. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- "Sesquicentennial Message from President". Iowa State University. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- "Iowa State: 150 Points of Pride". Iowa State University. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- "The National Schools of Science", The Nation: 409, November 21, 1867

- Roger L. Geiger & Nathan M. Sorber, The Land-Grant Colleges and the Reshaping of American Higher Education (Transaction Press, 2013)

- 7 U.S.C. § 323

- Ehrlich, Isaac; Cook, Adam; Yin, Yong (2018). "What Accounts for the US Ascendancy to Economic Superpower by the Early Twentieth Century? The Morrill Act–Human Capital Hypothesis". Journal of Human Capital. 12 (2): 233–281. doi:10.1086/697512. S2CID 158105754.

- Gavazzi, S. M.; Gee, E. G. (2018). Land-grant universities for the future: Higher education for the public good. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- "History of UGA". University of Georgia. University of Georgia. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Widder, Keith R. (2005). Michigan Agricultural College: The Evolution of a Land-grant Philosophy, 1855-1925. Michigan State University Press.

- Peter L. Moran; Roger L. Williams. "Saving the Land Grant for the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania". In Geiger, Roger L.; Sorber, Nathan M. (eds.). Land Grant Colleges and the Reshaping of American Higher Education. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 105–130.

- United States. Office of Special Assistant to the Postmaster General (1966). Postage Stamps of the United States. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 149.

- Nash, Margaret A. (November 2019). "Entangled Pasts: Land-Grant Colleges and American Indian Dispossession". History of Education Quarterly. 59 (4): 437–467. doi:10.1017/heq.2019.31.

- Nash, Margaret A. (November 8, 2019). "The Dark History of Land-Grant Universities". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Land Acknowledgement". University of Illinois System. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Land-grant colleges and universities. |

- Where the land came from, including maps showing individual parcels.