Education in the United States

Education in the United States of America is provided in public, private, and home schools. State governments set overall educational standards, often mandate standardized tests for K–12 public school systems and supervise, usually through a board of regents, state colleges, and universities. The bulk of the $1.3 trillion in funding comes from state and local governments, with federal funding accounting for only about $200 billion.[1] Private schools are generally free to determine their own curriculum and staffing policies, with voluntary accreditation available through independent regional accreditation authorities, although some state regulation can apply.

| United States Department of Education | |

|---|---|

| United States Secretary of Education | Phil Rosenfelt |

| National education budget (2016–17) | |

| Budget | $1.3 trillion (7.2% of GDP) (public and private, all levels)[1] |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | English |

| Literacy | |

| Male | 100%[2] |

| Female | 100%[2] |

| Enrollment | |

| Total | 81.5 million |

| Primary | 37.9 million1 |

| Secondary | 26.1 million (2006–2007) |

| Post secondary | 20.5 million 2 |

| Attainment | |

| Secondary diploma | 91%[3][4][5] |

| Post-secondary diploma | 46%[6][7] |

| 1 Includes kindergarten 2 Includes graduate school | |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

In 2013, about 87% of school-age children (those below higher education) attended state funded public schools, about 10% attended tuition- and foundation-funded private schools,[8] and roughly 3% were home-schooled.[9]

By state law, education is compulsory over an age range starting between five and eight and ending somewhere between ages sixteen and eighteen, depending on the state.[10] This requirement can be satisfied in public schools, state-certified private schools, or an approved home school program. In most schools, compulsory education is divided into three levels: elementary school, middle or junior high school, and high school. Children are usually divided by age groups into grades, ranging from kindergarten (5- to 6-year-olds) and first grade (6- to 7-year-olds) for the youngest children, up to twelfth grade (17- to 18-year-olds) as the final year of high school.

There is also a large number and wide variety of publicly and privately administered colleges and universities throughout the country. Post-secondary education, divided into college, as the first tertiary degree, and graduate school. Higher education includes extremely wealthy and selective universities, public research universities, private liberal arts colleges, historically-black colleges and universities, community colleges, for-profit colleges, and many other kinds and combinations of institutions. College enrollment rates in the United States have increased over the long term.[11] At the same time, student loan debt has also risen to $1.5 trillion. According to a 2016 report published by the U.S. News & World Report, of the top ten colleges and universities in the world, eight are American (the other two are Oxford and Cambridge, in the United Kingdom).[12]

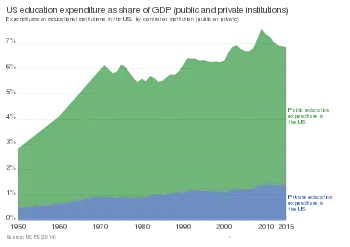

The United States spends more per student on education than any other country.[13] In 2014, the Pearson/Economist Intelligence Unit rated US education as 14th best in the world. The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD currently ranks the overall knowledge and skills of American 15-year-olds as 31st in the world in reading literacy, mathematics, and science with the average American student scoring 487.7, compared with the OECD average of 493.[14][15] In 2014, the country spent 6.2 percent of its GDP on all levels of education – 1.0 percentage points above the OECD average of 5.2 percent.[16] In 2017, 46.4 percent of Americans aged 25 to 64 attained some form of post-secondary education.[6][7] 48 percent of Americans aged 25 to 34 attained some form of tertiary education, about 4 percent above the OECD average of 44 percent.[17][18][19] 35 percent of Americans aged 25 and over have achieved a bachelor's degree or higher.[20] The United States ranks 3rd from the bottom among OECD nations in terms of its poverty gap, and 4th from the bottom in terms of poverty rate.[21][22]

History

19th century

Colonial New England encouraged its towns to support free public schools funded by taxation. In the early 19th century Massachusetts took the lead in education reform and public education with programs designed by Horace Mann that were widely emulated across the North. Teachers were specially trained in normal schools and taught the three Rs (of reading, writing, and arithmetic) and also history and geography. Public education was at the elementary level in most places. After the Civil War (1861–1865), the cities began building high schools. The South was far behind northern standards on every educational measure and gave weak support to its segregated all-black schools. However northern philanthropy and northern churches provided assistance to private black colleges across the South. Religious denominations across the country set up their private colleges. States also opened state universities, but they were quite small until well into the 20th century.

In 1823, Samuel Read Hall founded the first normal school, the Columbian School in Concord, Vermont,[23][24] aimed at improving the quality of the burgeoning common school system by producing more qualified teachers.

During Reconstruction, the Office of Education was created in an attempt to standardize educational reform across the country. At the outset, the goals of the Office were to track statistical data on schools and provide insight into the educational outcomes of schools in each state. While supportive of educational improvement, the office lacked the power to enforce policies in any state. Educational aims across the states in the nineteenth century were broad, making it difficult to create shared goals and priorities. States like Massachusetts, with long established educational institutions, had well-developed priorities in place by the time the Office of Education was established. In the South and the West, however, newly-formed common school systems had different needs and priorities.[25] Competing interests among state legislators limited the ability of the Office of Education to enact change.

In the mid-20th century, the rapidly increasing Catholic population led to the formation of parochial schools in the largest cities. Theologically oriented Episcopalian, Lutheran, and Jewish bodies on a smaller scale set up their own parochial schools. There were debates over whether tax money could be used to support them, with the answer typically being no. From about 1876, thirty-nine states passed a constitutional amendment to their state constitutions, called Blaine Amendments after James G. Blaine, one of their chief promoters, forbidding the use of public tax money to fund local parochial schools.

States passed laws to make schooling compulsory between 1852 (Massachusetts) and 1917 (Mississippi). They also used federal funding designated by the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Acts of 1862 and 1890 to set up land grant colleges specializing in agriculture and engineering. By 1870, every state had free elementary schools,[26] albeit only in urban centers. According to a 2018 study in the Economic Journal, states were more likely to adopt compulsory education laws during the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1914) if they hosted more European immigrants with lower exposure to civic values.[27]

Following Reconstruction the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute was founded in 1881 as a state college, in Tuskegee, Alabama, to train "Colored Teachers," led by Booker T. Washington, (1856–1915), who was himself a freed slave. His movement spread, leading many other Southern states to establish small colleges for "Colored or Negro" students entitled "A. & M." ("Agricultural and Mechanical") or "A. & T." ("Agricultural and Technical"), some of which later developed into state universities. Before the 1940s, there were very few black students at private or state colleges in the North, and almost none in the South.[28]

Responding to the many competing academic philosophies being promoted at the time, an influential working group of educators, known as the Committee of Ten and established in 1892 by the National Education Association, recommended that children should receive twelve years of instruction, consisting of eight years of elementary education (in what were also known as "grammar schools") followed by four years in high school ("freshmen," "sophomores," "juniors," and "seniors").

Gradually by the late 1890s, regional associations of high schools, colleges and universities were being organized to coordinate proper accrediting standards, examinations, and regular surveys of various institutions in order to assure equal treatment in graduation and admissions requirements, as well as course completion and transfer procedures.

20th century

By 1910, 72 percent of children were attending school. Private schools spread during this time, as well as colleges and – in the rural centers – land grant colleges also. Between 1910 and 1940 the high school movement resulted in a rapid increase in public high school enrollment and graduations. By 1930, 100 percent of children were attending school (excluding children with significant disabilities or medical concerns).[29]

By 1938 there was a movement to bring education to six years of elementary school, four years of junior high school, and four years of high school.[30]

During World War II, enrollment in high schools and colleges plummeted as many high school and college students—and teachers—dropped out to enlist or take war jobs.[31][32][33]

The 1946 National School Lunch Act, which is still in operation, provided low-cost or free school lunch meals to qualified low-income students through subsidies to schools, based on the idea that a "full stomach" during the day supported class attention and studying.

The 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas made racial desegregation of public elementary and high schools mandatory, although white families often attempted to avoid desegregation by sending their children to private secular or religious schools.[34][35][36] In the years following this decision, the number of Black teachers rose in the North but dropped in the South.[37]

In 1965, the far-reaching Elementary and Secondary Education Act ('ESEA'), passed as a part of President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty, provided funds for primary and secondary education ('Title I funding'). Title VI explicitly forbade the establishment of a national curriculum.[38] Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 created the Pell Grant program which provides financial support to students from low-income families to access higher education.

In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act established funding for special education in schools.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 made standardized testing a requirement. The Higher Education Amendments of 1972 made changes to the Pell Grants. The 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) required all public schools accepting federal funds to provide equal access to education and one free meal a day for children with physical and mental disabilities. The 1983 National Commission on Excellence in Education report, famously titled A Nation at Risk, touched off a wave of local, state, and federal reform efforts, but by 1990 the country still spent only 2 percent of its budget on education, compared with 30 percent on support for the elderly.[39] In 1990, the EHA was replaced with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which placed more focus on students as individuals, and also provided for more post-high school transition services.

21st century

The 2002 No Child Left Behind Act, passed by a bipartisan coalition in Congress provided federal aid to the states in exchange for measures to penalize schools that were not meeting the goals as measured by standardized state exams in mathematics and language skills.[40][41][42] In the same year, the U.S. Supreme Court diluted some of the century-old "Blaine" laws upheld an Ohio law allowing aid to parochial schools under specific circumstances.[43] The 2006 Commission on the Future of Higher Education evaluated higher education. In December 2015, President Barack Obama signed legislation replacing No Child Left Behind with the Every Student Succeeds Act.[44]

The Great Recession of 2008–09 caused a sharp decline in tax revenues in all cities and states. The response was to cut education budgets. Obama's $800 billion stimulus package included $100 billion for public schools, which every state used to protect its education budget. In terms of sponsoring innovation, however, Obama and his Education Secretary Arne Duncan pursued K-12 education reform through the Race to the Top grant program. With over $15 billion of grants at stake, 34 states quickly revised their education laws according to the proposals of advanced educational reformers. In the competition, points were awarded for allowing charter schools to multiply, for compensating teachers on a merit basis including student test scores, and for adopting higher educational standards. There were incentives for states to establish college and career-ready standards, which in practice meant adopting the Common Core State Standards Initiative that had been developed on a bipartisan basis by the National Governors Association, and the Council of Chief State School Officers. The criteria were not mandatory, they were incentives to improve opportunities to get a grant. Most states revised their laws accordingly, even though they realized it was unlikely they would win a highly competitive new grant. Race to the Top had strong bipartisan support, with centrist elements from both parties. It was opposed by the left wing of the Democratic Party, and by the right wing of the Republican Party, and criticized for centralizing too much power in Washington. Complaints also came from middle-class families, who were annoyed at the increasing emphasis on teaching to the test, rather than encouraging teachers to show creativity and stimulating students' imagination.[45][46]

In the 2010s, student loan debt became recognized as a social problem.[47][48][49][50][51]

COVID-19 pandemic

In the past centuries, education has been labeled a priority for the future of the United States. Therefore, the continuation of learning is crucial no matter the economic standing of the United States. While the United States has questioned the continuation of education in the past, the unexpected introduction of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has proposed a threat to traditional public and private school systems. As of March 16, 2020 more than half of the 50 states in the United States have shut down all of their schools[52] in response to COVID-19. With the rest of the school semester being unclear, school systems have been taking a remote approach. By March 26 and May 27, schools are transitioning classes to online, homeschool style learning.[53] This transition has challenged the United States Education System to adapt to at-home or home-school style learning utilizing technology.

In the 21st Century, technology has been a leading recipe to education, and this pandemic shows just that. Although the global coronavirus pandemic forced United States schools' to depend on technology, studies have proved the success with using technology as an educational tool. Technology offers students high quality, current, and relevant information making it easier to process.[54] While it is important for students to receive the most up-to-date information whether learning from home or at school, teachers can also direct students to trusted and informal sources to prevent confusion or misunderstandings. Over the years, data analytics has become embedded in almost every industry's data management, including education.[55] Data Analytics is the science of collecting and analyzing raw data to come up with conclusions based specifically on the data.[56] Educational platforms use data analytics to pinpoint areas of concern for particular students. Based on the students performance, teachers can alter their teaching styles and strategies to accommodate students based on their areas of concerns.[57] Utilizing technology in and outside of the classroom will make you viable to learning other technological skills.[57] Technological skills can vary from communicating by using text, to communicating information through graphs and charts. The usage of technology for educational purposes has also been presumed to improve student participation.[57] Technology acts as an "engagement booster" for students who would not normally speak or participate in the classrooms. When attempting to ask for opinions, teachers can create polling systems, to assure all students are engaged and participating. Based on the classroom performance, teachers can also exercise their creativity through quiz customizations.[57] Teachers can make polling and custom quizzes more engaging and competitive if they choose. In previous years, teachers would spend majority of their time keeping track of attendance, noting tasks completed, and recording quiz and test scores. With the technology the United States Education System has now, these tasks can be fully automated and noted.[57] Considering attendance and grading being automated, teachers can invest that time into other learning activities or strategies.

Although technology has displayed positive outcomes, studies also highlight the negative impact technology can have on the United States of America's Education System. One of the issues regarding technology is the issue of speed.[57] While we can receive information at significant speeds via technology, the accuracy of the information is at stake. Media use is subject to modifications that can change the overall representation of a video, photo or text. With technology acting as a learning tool, technology can also be viewed as a distraction.[57] With so many things out there in the world to study, and so many functions available on these technological devices, it is easy for young adults to fall victim to internet browsing. As mentioned before, technology can engage students whom choose not to speak or participate, however technology generates less verbal communications amongst classmates and teacher.[57] In the United States of America, there is a significant gap between students' of privileged and disadvantaged backgrounds.[58] While virtually almost all students in privileged households have laptops or computers in their household, around 25% of students from disadvantaged backgrounds did not have that technology in their households.[58] The effectiveness of online learning does not only vary amongst social class. Studies have proved that online learning can have more of a negative impact on you at younger ages than at older ages. For younger students it is almost required they have a structured environment.[58] Within structured environment, younger students are more capable of growing in discipline and communication skills. It is a challenge for most teachers to make their learning activities fun and engaging to the younger audience.

In response to COVID-19, many online learning platforms are making their services free due to the high demand. An online tutoring and educational firm, BYJU's, was one of the online learning platforms offering their services free of charge. BYJU's is based in Bangalore, and has seen a 200% increase in the number of students using their services, due to COVID-19. The coronavirus pandemic has resulted in the largest "online movement" in the history of education[58] with approximately 730,000 students actively attending classes via the Tencent Online school in Wuhan, China. While online learning platforms have began to transition their service to free of charge, some school districts are forming partnerships to offer local educational broadcasts for a variety of age groups. One of the partnerships formulated include The Los Angeles Unified School District and PBS SoCal/ KCET.[58] This partnership is offering educational broadcasts to users varying in age groups. The Los Angeles Unified School District and PBS SoCal/ KCET partnership is offering separate channels designated to specific age groups.

Statistics

In 2000, 76.6 million students had enrolled in schools from kindergarten through graduate schools. Of these, 72 percent aged 12 to 17 were considered academically "on track" for their age, i.e. enrolled in at or above grade level. Of those enrolled elementary and secondary schools, 5.2 million (10.4 percent) were attending private schools.

Over 85 percent of the adult population have completed high school and 27 percent have received a bachelor's degree or higher. The average salary for college or university graduates is greater than $51,000, exceeding the national average of those without a high school diploma by more than $23,000, according to a 2005 study by the U.S. Census Bureau.[59] The 2010 unemployment rate for high school graduates was 10.8%; the rate for college graduates was 4.9%. [60]

The country has a reading literacy rate of 99% of the population over age 15,[61] while ranking below average in science and mathematics understanding compared to other developed countries.[62] In 2014, a record high of 82% of high school seniors graduated, although one of the reasons for that success might be a decline in academic standards.[63]

The poor performance has pushed public and private efforts such as the No Child Left Behind Act. In addition, the ratio of college-educated adults entering the workforce to general population (33%) is slightly below the mean of other developed countries (35%)[64] and rate of participation of the labor force in continuing education is high.[65] A 2000s (decade) study by Jon Miller of Michigan State University concluded that "A slightly higher proportion of American adults qualify as scientifically literate than European or Japanese adults".[66]

In 2006, there were roughly 600,000 homeless students in the United States, but after the Great Recession this number more than doubled to approximately 1.36 million.[67] The Institute for Child Poverty and Homelessness keeps track of state by state levels of child homelessness.[68] As of 2017, 27% of US students live in a mother-only household, 20% live in poverty, and 9% are non-English speaking.[69]

Test performance

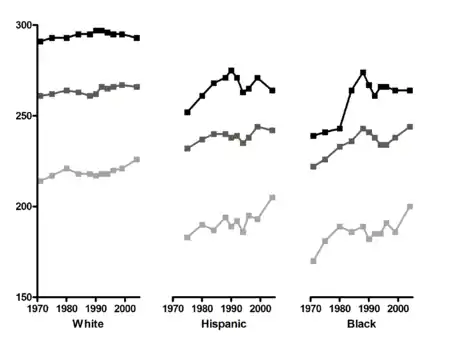

The test scores of students attending U.S. public schools are lower than student scores in schools of other developed countries, in the areas of reading, math, and science.[70]

Out of 21 industrialized countries, U.S. 12th graders ranked 19th in math, 16th in science, and last in advanced physics.

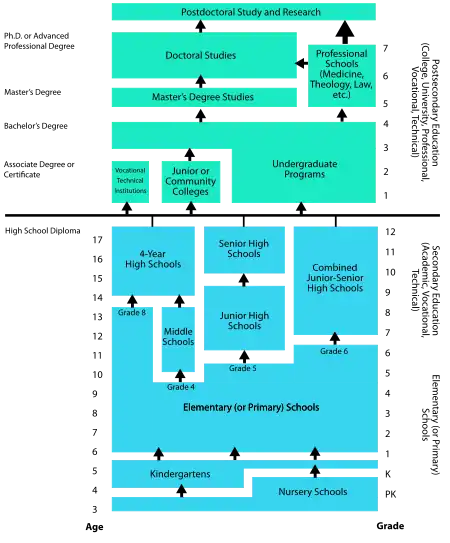

Educational stages

Formal education in the U.S. is divided into a number of distinct educational stages. Most children enter the public education system around ages five or six. Children are assigned into year groups known as grades.

The American school year traditionally begins at the end of August or early in September, after a traditional summer vacation or break. Children customarily advance together from one grade to the next as a single cohort or "class" upon reaching the end of each school year in late May or early June.

Depending upon their circumstances, children may begin school in pre-kindergarten, kindergarten or first grade. Students normally attend 12 grades of study over 12 calendar years of primary/elementary and secondary education before graduating and earning a diploma that makes them eligible for admission to higher education. Education is mandatory until age 16 (18 in some states).

In the U.S., ordinal numbers (e.g., first grade) are used for identifying grades. Typical ages and grade groupings in contemporary, public and private schools may be found through the U.S. Department of Education. Generally there are three stages: elementary school (K–5th grade), middle school (6th–8th grades) and high school (9th–12th grades).[71]

There is considerable variability in the exact arrangement of grades, as the following table indicates. Note that many people may not choose to attain higher education immediately after high school graduation, so the age of completing each level of education may vary. The table below shows the traditional education path of a student completing an undergraduate degree immediately after high school.

| Category | School Grade Level | Ages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool education | Pre-kindergarten | 3-5 | |||

| Compulsory education | |||||

| Elementary school | Kindergarten | 5-6 | |||

| 1st grade | 6-7 | ||||

| 2nd grade | 7-8 | ||||

| 3rd grade | 8-9 | ||||

| 4th grade | 9-10 | ||||

| 5th grade | 10-11 | ||||

| Middle school | 6th grade | 11-12 | |||

| Junior high school | 7th grade | 12-13 | |||

| 8th grade | 13-14 | ||||

| High school | Freshman/9th grade | 14-15 | |||

| Senior high school | Sophomore/10th grade | 15-16 | |||

| Junior/11th grade | 16-17 | ||||

| Senior/12th grade | 17-18 | ||||

| Higher education | |||||

| College (University) | Undergraduate school | First year: "freshman year" | 18-19 | ||

| Second year: "sophomore year" | 19-20 | ||||

| Third year: "junior year" | 20-21 | ||||

| Fourth year: "senior year" | 21-22 | ||||

| Graduate school (with various degrees and curricular partitions thereof) | 22 and up | ||||

| Continuing education | |||||

| Vocational school | 18 and up | ||||

| Adult education | |||||

Variations

In K–12 education, sometimes students who receive failing grades are held back a year and repeat coursework in the hope of earning satisfactory scores on the second try.

High school graduates sometimes take one or more gap years before the first year of college, for travel, work, public service, or independent learning.

Many undergraduate college programs now commonly are five-year programs. This is especially common in technical fields, such as engineering. The five-year period often includes one or more periods of internship with an employer in the chosen field.

Of students who were freshmen in 2005 seeking bachelor's degrees at public institutions, 32% took four years, 12% took five years, 6% took six years, and 43% did not graduate within six years. The numbers for private non-profit institutions were 52% in four, 10% in five, 4% in six, and 35% failing to graduate.[72]

Some undergraduate institutions offer an accelerated three-year bachelor's degree, or a combined five-year bachelor's and master's degrees. Many times, these accelerated degrees are offered online or as evening courses and are targeted mainly but not always for adult learners/non-traditional students.

Many graduate students do not start professional schools immediately after finishing undergraduate studies, but work for a time while saving up money or deciding on a career direction.

The National Center for Education Statistics found that in 1999–2000, 73% of people attending institutions of higher education were non-traditional students.[73]

Early childhood education

Early childhood teaching in the US relates to the teaching of [children (formally and informally) from birth up to the age of eight.[74] The education services are delivered via preschools and kindergartens.

Preschool

Preschool (sometimes called pre-kindergarten or jr. kindergarten) refers to non-compulsory classroom-based early-childhood education. The Head Start program is a federally funded early childhood education program for low-income children and their families founded in 1965 prepares children, especially those of a disadvantaged population, to better succeed in school. However, limited seats are available to students aspiring to take part in the Head Start program. Many community-based programs, commercial enterprises, non-profit organizations, faith communities, and independent childcare providers offer preschool education. Preschool may be general or may have a particular focus, such as arts education, religious education, sports training, or foreign language learning, along with providing general education. In the United States, Preschool programs are not required, however they are encouraged by educators. Only 69 percent of 4-year-old American children are enrolled in preschool. Preschool age ranges anywhere from 3 to 5 years old. The curriculum for the day will consist of music, art, pretend play, science, reading, math, and other social activities.

K–12 education

Schooling is compulsory for all children in the United States, but the age range for which school attendance is required varies from state to state. Some states allow students to leave school between 14 and 17 with parental permission, before finishing high school; other states require students to stay in school until age 18.[75] Public (free) education is typically from kindergarten to grade 12 (frequently abbreviated K–12). Children who do not comply with compulsory attendance laws without good cause are deemed to be truants, and they and their parents may be subject to various penalties under state law.

Most parents send their children to either a public or private institution. According to government data, one-tenth of students are enrolled in private schools. Approximately 85% of students enter the public schools,[76] largely because they are tax-subsidized (tax burdens by school districts vary from area to area). School districts are usually separate from other local jurisdictions, with independent officials and budgets.

There are more than 14,000 school districts in the country,[77] and more than $500 billion is spent each year on public primary and secondary education.[77] Most states require that their school districts within the state teach for 180 days a year.[78] In 2010, there were 3,823,142 teachers in public, charter, private, and Catholic elementary and secondary schools. They taught a total of 55,203,000 students, who attended one of 132,656 schools.[79]

Most children begin elementary education with kindergarten (usually five to six years old) and finish secondary education with twelfth grade (usually 17–18 years old). In some cases, pupils may be promoted beyond the next regular grade. Parents may also choose to educate their own children at home; 1.7% of children are educated in this manner.[76]

Around 3 million students between the ages of 16 and 24 drop out of high school each year, a rate of 6.6 percent as of 2012. In the United States, 75 percent of crimes are committed by high school dropouts. Around 60 percent of black dropouts end up spending time incarcerated.[80] The incarceration rate for African-American male high school dropouts was about 50 times the national average as of 2010.[81]

States do not require reporting from their school districts to allow analysis of efficiency of return on investment. The Center for American Progress commends Florida and Texas as the only two states that provide annual school-level productivity evaluations which report to the public how well school funds are being spent at the local level. This allows for comparison of school districts within a state.[82] In 2010, American students rank 17th in the world. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development says that this is due to focusing on the low end of performers. All of the recent gains have been made, deliberately, at the low end of the socioeconomic scale and among the lowest achievers. The country has been outrun, the study says, by other nations because the US has not done enough to encourage the highest achievers.[83]

About half of the states encourage schools to make their students recite the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag daily.[84]

Teachers worked from about 35 to 46 hours a week, in a survey taken in 1993.[85] In 2011, American teachers worked 1,097 hours in the classroom, the most for any industrialized nation measured by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. They spend 1,913 hours a year on their work, just below the national average of 1,932 hours for all workers.[86] In 2011, the average annual salary of a preK–12 teacher was $55,040.[87]

Transporting students to and from school is a major concern for most school districts. School buses provide the largest mass transit program in the country, 8.8 billion trips per year. Non-school transit buses give 5.2 billion trips annually. 440,000 yellow school buses carry over 24 million students to and from schools.[88] In 1971, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that forced busing of students may be ordered to achieve racial desegregation.[89] This ruling resulted in a white flight from the inner cities which largely diluted the intent of the order. This flight had other, non-educational ramifications as well. Integration took place in most schools though de facto segregation often determined the composition of the student body. By the 1990s, most areas of the country had been released from mandatory busing.

School start times are computed with busing in mind. There are often three start times: for elementary, for middle/junior high school, and for high school. One school district computed its cost per bus (without the driver) at $20,575 annually. It assumed a model where the average driver drove 80 miles per day. A driver was presumed to cost $.62 per mile (1.6 km). Elementary schools started at 7:30, middle schools/junior high school started at 8:30, and high schools at 8:15. While elementary school started earlier, they also finish earlier, at 2:30, middle schools at 3:30 and high schools at 3:20.[90] All school districts establish their own times and means of transportation within guidelines set by their own state.

Grade placement

Schools use several methods to determine grade placement. One method involves placing students in a grade based on a child's birthday. Cut off dates based on the child's birthday determine placement in either a higher or lower grade level. For example, if the school's cut off date is September 1, and an incoming student's birthday is August 2, then this student would be placed in a higher grade level.[91] If the student is in high school, this could mean that the student gets placed as a 11th grade instead of a 10th because of their birthday. Content each grade aligns with age and academic goals for the expected age of the students. Generally a student is expected to advance a grade each year K-12, however if a student under-performs, he or she may retake that grade.

Primary education

Historically, in the United States, local public control (and private alternatives) have allowed for some variation in the organization of schools. Elementary school includes kindergarten through sixth grade (or sometimes, to fourth grade, fifth grade or eighth grade). Basic subjects are taught in elementary school, and students often remain in one classroom throughout the school day, except for specialized programs, such as physical education, library, music, and art classes. There are (as of 2001) about 3.6 million children in each grade in the United States.[92]

Typically, the curriculum in public elementary education is determined by individual school districts or county school system. The school district selects curriculum guides and textbooks that reflect a state's learning standards and benchmarks for a given grade level. The most recent curriculum that has been adopted by most states is Common Core.[93] Learning Standards are the goals by which states and school districts must meet adequate yearly progress (AYP) as mandated by No Child Left Behind (NCLB). This description of school governance is simplistic at best, however, and school systems vary widely not only in the way curricular decisions are made but also in how teaching and learning take place. Some states or school districts impose more top-down mandates than others. In others, teachers play a significant role in curriculum design and there are few top-down mandates. Curricular decisions within private schools are often made differently from in public schools, and in most cases without consideration of NCLB.

Public elementary school teachers typically instruct between twenty and thirty students. A typical classroom will include children with a range of learning needs or abilities, from those identified as having special needs of the kinds listed in the Individuals with Disabilities Act IDEA to those that are cognitively, athletically or artistically disabled. At times, an individual school district identifies areas of need within the curriculum. Teachers and advisory administrators form committees to develop supplemental materials to support learning for diverse learners and to identify enrichment for textbooks. There are special education teachers working with the identified students. Many school districts post information about the curriculum and supplemental materials on websites for public access.[94]

In general, a student learns basic arithmetic and sometimes rudimentary algebra in mathematics, English proficiency (such as basic grammar, spelling, and vocabulary), and fundamentals of other subjects. Learning standards are identified for all areas of a curriculum by individual States, including those for mathematics, social studies, science, physical development, the fine arts, and reading.[93] While the concept of State Learning standards has been around for some time, No Child Left Behind has mandated that standards exist at the State level.

Secondary education

Secondary education is often divided into two phases, middle/junior high school and high school. Students are usually given more independence, moving to different classrooms for different subjects, and being allowed to choose some of their class subjects (electives).

"Middle school" (or "junior high school") has a variable range between districts. It usually includes seventh and eighth grades and occasionally also includes one or more of the sixth, ninth, and very occasionally fifth grades as well. High school (occasionally senior high school) includes grades 9 through 12. Students in these grades are commonly referred to as freshmen (grade 9), sophomores (grade 10), juniors (grade 11) and seniors (grade 12). At the high school level, students generally take a broad variety of classes without specializing in any particular subject, with the exception of vocational schools. Students are generally required to take a broad range of mandatory subjects, but may choose additional subjects ("electives") to fill out their required hours of learning. High school grades normally are included in a student's official transcript, e.g. for college admission. Official transcripts usually include the ninth grade, whether it is taught in a middle school or a high school.

Each state sets minimum requirements for how many years of various mandatory subjects are required; these requirements vary widely, but generally include 2–4 years of each of: Science, Mathematics, English, Social sciences, Physical education; some years of a foreign language and some form of art education are often also required, as is a health curriculum in which students learn about anatomy, nutrition, first aid, sexuality, drug awareness, and birth control. In many cases, however, options are provided for students to "test out" of this requirement or complete independent study to meet it.

Many high schools provide Honors, Advanced Placement (AP) or International Baccalaureate (IB) courses. These are special forms of honors classes where the curriculum is more challenging and lessons more aggressively paced than standard courses. Honors, AP or IB courses are usually taken during the 11th or 12th grade of high school, but may be taken as early as 9th grade. Some international schools offer international school leaving qualifications, to be studied for and awarded instead of or alongside of the high school diploma, Honors, Advanced Placement, or International Baccalaureate. Regular honors courses are more intense and faster paced than typical college preparatory courses. AP and IB on the other hand, are college-level classes.

Tracking (streaming)

Tracking is the practice of dividing students at the primary or secondary school level into classes on the basis of ability or achievement. One common use is to offer different curricula for students preparing for college and for those preparing for direct entry into technical schools or the workplace.

Grading scale

In schools in the United States children are assessed throughout the school year by their teachers, and report cards are issued to parents at varying intervals. Generally the scores for individual assignments and tests are recorded for each student in a grade book, along with the maximum number of points for each assignment. End-of-term or -year evaluations are most frequently given in the form of a letter grade on an A-F scale, whereby A is the best possible grade and F is a failing grade (most schools do not include the letter E in the assessment scale), or a numeric percentage. The Waldorf schools,[95][96] most democratic schools,[97] and some other private schools, give (often extensive) verbal characterizations of student progress rather than letter or number grades. Some school districts allow flexibility in grading scales at the Student information system level, allowing custom letters or symbols to be used (though transcripts must use traditional A-F letters)

| A | B | C | D | F | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | |||||||

| 100.0–97.0 | 96.9–93.0 | 92.9–90.0 | 89.9–87.0 | 86.9–83.0 | 82.9–80.0 | 79.9–77.0 | 76.9–73.0 | 72.9–70.0 | 69.9–67.0 | 66.9–63.0 | 62.9–60.0 | 59.9–0.0 | ||

Traditionally, Colleges and Universities tend to take on the formal letter grading scale, consisting of A, B, C, D, and F, as a way to base ones performance. In result to the COVID-19 pandemic, most Colleges and Universities were flooded with petitions proposing pass or fail options for students considering the difficulties with transitioning and managing during a state of emergency. Although most colleges and universities empathized with students expressing their frustration with transitioning online, transfer students implementing the pass or fail option are forecasted to having to retake the class.[98] College credits for pass or fail classes have a low rate of being accepted by other colleges, forcing transfer students to sit through and pay for the same class they have already completed. While some colleges, such as the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Carnegie Mellon University, and North Carolina are permitting their students from weeks to months, to decide whether they will implement the pass or fail option offered by their college.[98] While Harvard Medical School has previously been opposed to pass or fail grades, they have opened up to accepting pass grades.

Standardized testing

Under the No Child Left Behind Act and Every Student Succeeds Acts, all American states must test students in public schools statewide to ensure that they are achieving the desired level of minimum education,[99] such as on the New York Regents Examinations, the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT) and the Florida Standards Assessments (FSA) or the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS); students being educated at home or in private schools are not included. The act also required that students and schools show adequate yearly progress. This means they must show some improvement each year. When a student fails to make adequate yearly progress, NCLB mandated that remediation through summer school or tutoring be made available to a student in need of extra help. On December 10, 2015 President Barack Obama signed legislation replacing NCLB with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).[44] However, the enactment of ESSA did not eliminate provisions relating to the periodic standardized tests given to students.[100][101]

Academic performance impacts the perception of a school's educational program. Rural schools fare better than their urban counterparts in two key areas: test scores and drop-out rate. First, students in small schools performed equal to or better than their larger school counterparts.[102] In addition, on the 2005 National Assessment of Education Progress, 4th and 8th grade students scored as well or better in reading, science, and mathematics.[103]

During high school, students (usually in 11th grade) may take one or more standardized tests depending on their post-secondary education preferences and their local graduation requirements. In theory, these tests evaluate the overall level of knowledge and learning aptitude of the students. The SAT and ACT are the most common standardized tests that students take when applying to college. A student may take the SAT, ACT, both, or neither depending upon the post-secondary institutions the student plans to apply to for admission. Most competitive post-secondary institutions also require two or three SAT Subject Tests (formerly known as SAT IIs), which are shorter exams that focus strictly on a particular subject matter. However, all these tests serve little to no purpose for students who do not move on to post-secondary education, so they can usually be skipped without affecting one's ability to graduate.

Standardized testing has become increasingly controversial in recent years. Creativity and the need for applicable knowledge are becoming rapidly more valuable than simple memorization. Opponents of standardized education[104] have stated that it is the system of standardized education itself[105] that is to blame for employment issues and concerns over the questionable abilities of recent graduates.[106][107][108][109] Others consider standardized tests to be a valuable objective check on grade inflation. In recent years, grade point averages (particularly in suburban schools) have been rising while SAT scores have been falling.[110] Standardized test demonstrates a schools improvement on state assessment test. However, it has been shown that this kind of testing does not improve students "fluid intelligence".[111] What standardized testing is actually testing is the ability to recall information quickly from a short-term memory. They are not requiring students to use logical thinking, problem solving, or long-term memory.[111] Suggestions for improving standardized testing include evaluating a student's overall growth, possibly including non-cognitive qualities such as social and emotional behaviors, not just achievement; introducing 21st century skills and values; and making the tests open-ended, authentic, and engaging.[112]

Most Universities are eliminating standardized testing due to the unfairness toward the candidates expected to participate in later test dates. According to Harvard College, this year they will make standardized test scores optional, empathizing with students having trouble scheduling exams during the coronavirus pandemic.[113]

Extracurricular activities

A major characteristic of American schools is the high priority given to sports, clubs and activities by the community, the parents, the schools and the students themselves.[114] Extracurricular activities are educational activities not falling within the scope of the regular curriculum but under the supervision of the school. Extracurriculars at the high school age (15–18)[115] can be anything that doesn't require a high school credit or paid employment, but simply done out of pleasure or to also look good on a college transcript. Extracurricular activities for all ages can be categorized under clubs, art, culture and language, community, leadership, government, media, military, music, performing arts, religion, role play/fantasy, speech, sports, technology, and volunteer,[116] all of which take place outside of school hours. These sorts of activities are put in place as other forms of teamwork, time management, goal setting, self-discovery, building self-esteem, relationship building, finding interests, and academics. These extracurricular activities and clubs can be sponsored by fund raising, or by the donation of parents who give towards the program in order for it to keep running. Students and Parents are also obligated to spend money on whatever supplies are necessary for this activity that are not provided for the school (sporting equipment, sporting attire, costumes, food, instruments).[117] These activities can extend to large amounts of time outside the normal school day; home-schooled students, however, are not normally allowed to participate. Student participation in sports programs, drill teams, bands, and spirit groups can amount to hours of practices and performances. Most states have organizations that develop rules for competition between groups. These organizations are usually forced to implement time limits on hours practiced as a prerequisite for participation. Many schools also have non-varsity sports teams; however, these are usually afforded fewer resources and less attention.

Sports programs and their related games, especially football and basketball, are major events for American students and for larger schools can be a major source of funds for school districts.

High school athletic competitions often generate intense interest in the community.

In addition to sports, numerous non-athletic extracurricular activities are available in American schools, both public and private. Activities include Quizbowl,[118] musical groups, marching bands, student government, school newspapers, science fairs, debate teams, and clubs focused on an academic area (such as the Spanish Club) or community service interests (such as Key Club).[119]

Additional support needs

Students with special needs are typically taught by teachers with specialized training in adapting curricula. As of 2017, about 13% of US students receive special education services.[69]

According to the National Association of School Nurses, 5% of students in 2009 have a seizure disorder,[120] another 5% have ADHD and 10% have mental or emotional disorders.[121]

On January 25, 2013, the Office for Civil Rights of the US Department of Education issued guidance, clarifying school districts' existing legal obligations to give disabled students an equal chance to compete in extracurricular sports alongside their able-bodied classmates.[122]

- Educating children with disabilities

The federal law, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires states to ensure that all government-run schools provide services to meet the individual needs of students with special needs, as defined by the law.[123] All students with special needs are entitled to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE).

Schools meet with the parents or guardians to develop an Individualized Education Program that determines best placement for the child. Students must be placed in the least restrictive environment (LRE) that is appropriate for the student's needs.

In 2017, nationwide 67.1% of students with disabilities attending public schools graduated high school.[124]

- Criticism

At-risk students (those with educational needs that are not associated with a disability) are often placed in classes with students with minor emotional and social disabilities.[125] Critics assert that placing at-risk students in the same classes as these disabled students may impede the educational progress of both the at-risk and the disabled students. Some research has refuted this assertion, and has suggested this approach increases the academic and behavioral skills of the entire student population.[126]

Public and private schools

In the United States, state and local government have primary responsibility for education. The Federal Department of Education plays a role in standards setting and education finance, and some primary and secondary schools, for the children of military employees, are run by the Department of Defense.[127]

K–12 students in most areas have a choice between free tax-funded public schools, or privately funded private schools.

Public school systems are supported by a combination of local, state, and federal government funding. Because a large portion of school revenues come from local property taxes, public schools vary widely in the resources they have available per student. Class size also varies from one district to another. Curriculum decisions in public schools are made largely at the local and state levels; the federal government has limited influence. In most districts, a locally elected school board runs schools. The school board appoints an official called the superintendent of schools to manage the schools in the district.

Local property taxes for public school funding may have disadvantages depending on how wealthy or poor these cities may be. Some of the disadvantages may be not having the proper electives of students interest or advanced placement courses to further the knowledge and education of these students. Cases such as these limit students and causes inequality in education because there is no easy way to gain access to those courses since the education system might not view them as necessary. The public education system does provide the classes needed to obtain a GED (General Education Development) and obtain a job or pursue higher education.[128]

The largest public school system in the United States is in New York City, where more than one million students are taught in 1,200 separate public schools.

Admission to individual public schools is usually based on residency. To compensate for differences in school quality based on geography, school systems serving large cities and portions of large cities often have magnet schools that provide enrollment to a specified number of non-resident students in addition to serving all resident students. This special enrollment is usually decided by lottery with equal numbers of males and females chosen. Some magnet schools cater to gifted students or to students with special interests, such as the sciences or performing arts.[129]

Private schools in the United States include parochial schools (affiliated with religious denominations),[130] non-profit independent schools, and for-profit private schools. Private schools charge varying rates depending on geographic location, the school's expenses, and the availability of funding from sources, other than tuition. For example, some churches partially subsidize private schools for their members. Some people have argued that when their child attends a private school, they should be able to take the funds that the public school no longer needs and apply that money towards private school tuition in the form of vouchers. This is the basis of the school choice movement.

5,072,451 students attended 33,740 private elementary and secondary schools in 2007. 74.5% of these were Caucasian, non-Hispanic, 9.8% were African American, 9.6% were Hispanic. 5.4% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and .6% were American Indian. Average school size was 150.3 students. There were 456,266 teachers. The number of students per teacher was about 11. 65% of seniors in private schools in 2006–07 went on to attend a four-year college.[131]

Private schools have various missions: some cater to college-bound students seeking a competitive edge in the college admissions process; others are for gifted students, students with learning disabilities or other special needs, or students with specific religious affiliations. Some cater to families seeking a small school, with a nurturing, supportive environment. Unlike public school systems, private schools have no legal obligation to accept any interested student. Admission to some private schools is often highly selective.

An August 17, 2000 article by the Chicago Sun-Times refers to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago Office of Catholic Schools as the largest private school system in the United States.[132]

Charter schools

The charter school movement began in 1990 and have spread rapidly in the United States, members, parents, teachers, and students to allow for the "expression of diverse teaching philosophies and cultural and social life styles."[133]

Home schooling

In 2014, approximately 1.5 million children were homeschooled, up 84% from 1999 when the U.S. Department of Education first started keeping statistics. This was 2.9% of all children.[134]

As of spring 2016, there are 2.3 million homeschooled students in the United States. It is appearing that homeschooling is a continuing trend in the US with a 2 percent to 8 percent per annum over the past few years[135] Many select moral or religious reasons for homeschooling their children. The second main category is unschooling, those who prefer a non-standard approach to education.[134] This is a parent-led type of schooling that takes place at home and is now boarding a mainstream form of education in the United States. The Demography for homeschoolers has a variety of people; these are atheists, Christians, and Mormons; conservatives, libertarians, and liberals; low-, middle-, and high-income families; black, Hispanic, and white; parents with PhDs, GEDs, and no high-school diplomas. One study shows that 32 percent of homeschool students are Black, Asian, Hispanic, and others (i.e., not White/non-Hispanic). There is no required taxes on this form of education and most homeschooled families spend an average of $600 per student for their education[136]

Opposition to homeschooling comes from varied sources, including teachers' organizations and school districts. The National Education Association, the largest labor union in the United States, has been particularly vocal in the past.[137] Opponents' stated concerns fall into several broad categories, including fears of poor academic quality, and lack of socialization with others. At this time, over half of states have oversight into monitoring or measuring the academic progress of home schooled students, with all but ten requiring some form of notification to the state.[138]

Higher education

| Education | Percentage |

|---|---|

| High school graduate | 89.8% |

| Some college | 61.20% |

| Associate degree | 45.16% |

| Bachelor's degree | 34.9% |

| Master's degree | 13.05% |

| Doctorate or professional degree | 3.5% |

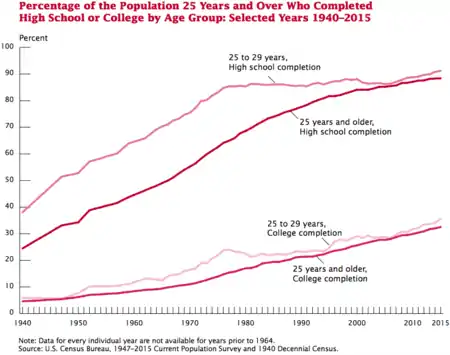

Higher education in the United States is an optional final stage of formal learning following secondary education, often at one of the 4,495 colleges or universities and junior colleges in the country.[139] In 2008, 36% of enrolled students graduated from college in four years. 57% completed their undergraduate requirements in six years, at the same college they first enrolled in.[140] The U.S. ranks 10th among industrial countries for percentage of adults with college degrees.[60] Over the past 40 years the gap in graduation rates for wealthy students and low income students has widened significantly. 77% of the wealthiest quartile of students obtained undergraduate degrees by age 24 in 2013, up from 40% in 1970. 9% of the least affluent quartile obtained degrees by the same age in 2013, up from 6% in 1970.[141]

There are over 7000 post-secondary institutions in the United States offering a diverse number of programs catered to students with different aptitudes, skills, and educational needs.[142] Compared with the higher education systems of other countries, post-secondary education in the United States is largely deregulated, giving students a variety of choices. Common admission requirements to gain entry to any American university requires a meeting a certain age threshold, high school transcript documenting grades, coursework, and rigour of core high school subject areas as well as performance in AP and IB courses, class ranking, ACT or SAT scores, extracurricular activities, an admissions essay, and letters of recommendation from teachers and guidance counselors. Other admissions criteria may include an interview, personal background, legacy preferences (family members having attended the school), ability to pay tuition, potential to donate money to the school development case, evaluation of student character (based on essays or interviews), and general discretion by the admissions office. While universities will rarely list that they require a certain standardized test score, class ranking, or GPA for admission, each university usually has a rough threshold below which admission is unlikely.

University

_seen_from_the_southeast_with_the_Italian_Pavilion_in_the_foreground.jpg.webp)

The traditional path to American higher education is typically through a college or university, the most prestigious forms of higher education in the United States. Universities in the United States are institutions that issue bachelor's, master's, professional, or doctorate degrees; colleges often award solely bachelor's degrees. Some universities offer programs at all degree levels from the associate to the doctorate, and are distinguished from community and junior colleges where the highest degree offered is the associate degree or a diploma. Though there is no prescribed definition of a "university" or "college" in the United States, universities are generally research-oriented institutions offering undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs. American universities come in a variety of forms that serve different educational needs. Some counties and cities have established and funded four-year institutions. Some of these institutions, such as the City University of New York, are still operated by local governments. Others such as the University of Louisville and Wichita State University are now operated as state universities. Four-year institutions may be public or private colleges or universities. Private institutions are privately funded and there is a wide variety in size, focus, and operation. Some private institutions are large research universities, while others are small liberal arts colleges that concentrate on undergraduate education. Some private universities are nonsectarian and secular, while others are religiously-affiliated.

Among the United States' most prominent and world renowned institutions are large research universities that are ranked in such annual publications such as the Times Higher Education World University Rankings, QS World University Rankings, U.S. News & World Report, Washington Monthly, ARWU, by test preparation services such as The Princeton Review or by another university such as the Top American Research Universities ranked by the University of Florida's The Center.[143] These rankings are based on factors such as brand recognition, number of Nobel Prize winners, selectivity in admissions, generosity of alumni donors, and volume and quality of faculty research. Among the top forty domestically and internationally ranked institutions identified by the QS 2020 rankings include six of the eight Ivy League schools; private universities Stanford, The University of Chicago, Johns Hopkins, Duke, Northwestern, and New York University; 2 of the 10 schools in the University of California system (UC Berkeley and UCLA); and the research intensive institutions CalTech and MIT.[144] Other types of universities in the United States include liberal arts schools (Reed College, Swarthmore College, Barnard College), religiously affiliated and denomination universities (DePaul University, Brigham Young University, Yeshiva University), military (United States Military Academy, United States Merchant Marine Academy, United States Naval Academy), art and design schools (Berklee College of Music, Juilliard School, Fashion Institute of Technology, Parsons School of Design, Rhode Island School of Design), Historically black colleges and universities (Morehouse College, Howard University, Kentucky State University), and for-profit universities (University of Phoenix, Western International University, Liberty University).[145] While most private institutions are non-profit, a growing number in the past decade have been established as for-profit. The American university curriculum varies widely depending on the program and institution. Typically, an undergraduate student will be able to select an academic "major" or concentration, which comprises the core main or special subjects, and students may change their major one or more times.

Some students, typically those with a bachelor's degree, may choose to continue on to graduate or professional school, which are graduate and professional institutions typically attached to a university. Graduate degrees may be either master's degrees (e.g., M.A., M.S., M.S.W.), professional degrees's (e.g. M.B.A., J.D., M.D.) or doctorate degrees (e.g. PhD). Programs range from full-time, evening and executive which allows for flexibility with students' schedules.[146] Academia-focused graduate school typically includes some combination of coursework and research (often requiring a thesis or dissertation to be written), while professional graduate-level schools grants a first professional degree. These include medical, law, business, education, divinity, art, journalism, social work, architecture, and engineering schools.

Vocational

Community and junior colleges in the United States are public comprehensive institutions that offer a wide range of educational services that generally lasts two years. Community colleges are generally publicly funded (usually by local cities or counties) and offer career certifications and part-time programs. Though it is cheaper in terms of tuition, less competitive to get into, and not as prestigious as going to a four-year university, they form another post-secondary option for students seeking to enter the realm of American higher education. Community and junior colleges generally emphasize practical career oriented education that is focused on a vocational curriculum.[147] Though some community and junior colleges offer accredited bachelor's degree programs, community and junior colleges typically offer a college diploma or an associate degree such as an A.A., A.S., or a vocational certificate, although some community colleges offer a limited number of bachelor's degrees. Community and junior colleges also offer trade school certifications for skilled trades and technical careers. Students can also earn credits at a community or junior college and transfer them to a four-year university afterwards. Many community colleges have relationships with four-year state universities and colleges or even private universities that enable some community college students to transfer to these universities to pursue a bachelor's degree after the completion of a two-year program at the community college.

Cost

A few charity institutions cover all of the students' tuition, although scholarships (both merit-based and need-based) are widely available. Generally, private universities charge much higher tuition than their public counterparts, which rely on state funds to make up the difference. Because each state supports its own university system with state taxes, most public universities charge much higher rates for out-of-state students.

Annual undergraduate tuition varies widely from state to state, and many additional fees apply. In 2009, average annual tuition at a public university (for residents of the state) was $7,020.[140] Tuition for public school students from outside the state is generally comparable to private school prices, although students can often qualify for state residency after their first year. Private schools are typically much higher, although prices vary widely from "no-frills" private schools to highly specialized technical institutes. Depending upon the type of school and program, annual graduate program tuition can vary from $15,000 to as high as $50,000. Note that these prices do not include living expenses (rent, room/board, etc.) or additional fees that schools add on such as "activities fees" or health insurance. These fees, especially room and board, can range from $6,000 to $12,000 per academic year (assuming a single student without children).[150]

The mean annual total cost (including all costs associated with a full-time post-secondary schooling, such as tuition and fees, books and supplies, room and board), as reported by collegeboard.com for 2010:[151]

- Public university (4 years): $27,967 (per year)

- Private university (4 years): $40,476 (per year)

Total, four-year schooling:

- Public university: $111,868

- Private university: $161,904

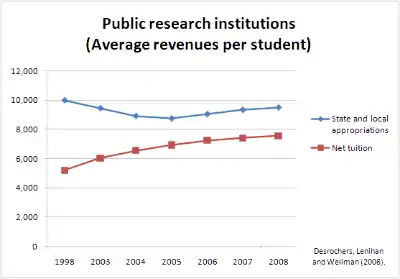

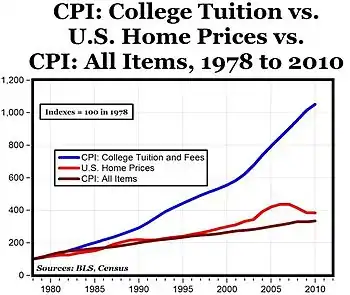

College costs are rising at the same time that state appropriations for aid are shrinking. This has led to debate over funding at both the state and local levels. From 2002 to 2004 alone, tuition rates at public schools increased over 14 percent, largely due to dwindling state funding. An increase of 6 percent occurred over the same period for private schools.[150] Between 1982 and 2007, college tuition and fees rose three times as fast as median family income, in constant dollars.[152]

From the US Census Bureau, the median salary of an individual who has only a high school diploma is $27,967; The median salary of an individual who has a bachelor's degree is $47,345.[153] Certain degrees, such as in engineering, typically result in salaries far exceeding high school graduates, whereas degrees in teaching and social work fall below.

The debt of the average college graduate for student loans in 2010 was $23,200.[154]

A 2010 study indicates that the return on investment for graduating from the top 1000 colleges exceeds 4% over a high school degree.[155]

Student loan debt

In 2018, student loan debt topped $1.5 trillion. More than 40 million people hold college debt, which is largely owned by the US government and serviced by companies such as Navient. Student loan debt has reached levels that have affected US society, reducing opportunities for millions of people following college.[156]

Sen. Bernie Sanders, as part of 2020 presidential campaign in June 2019, proposed a legislation that would free approximately 45 million Americans from a combined debt of $1.6 trillion as student loan. “We will make a full and complete education a human right,” Sanders said.[157]

Coronavirus Pandemic

With the unforeseen appearance of COVID-19, colleges and universities are in jeopardy of shutting down for good. Universities are being forced to refund money to students, invest in online technology and tools, making it harder to invest into empty campuses. Schools are defined as being in low financial health if their combined revenue and unrestricted assets will nolonger cover operating expenses in 6 years. Before COVID-19, 13 institutions were in danger of closing within 6 years in New England.[158] With the presence of COVID-19, that number has increased to 25 institutions.[158] Nationwide, because of the financial impact caused by the coronavirus pandemic, 110 more colleges and universities are now at risk of closing. This labels the total number of colleges and universities in peril due to coronavirus pandemic to be 345 institutions.[158] While prestigious colleges and universities have historically had financial cushion due to high levels of enrollment, private colleges at a low risk have dropped from 485 to 385.[158] Federal coronavirus relief has assisted students and universities, however it has not been enough to bandage the financial wound created by COVID-19. Colby-Sawyer College located in New Hampshire has received about $780,000 in assistance through the United States Department of Education.[158] About half of this money was dispersed amongst the student body. Colby-Swayer College was also capable of receiving a loan of $2.65 million, to avoid layoffs of their 312 employees.[158]

Academic labor and adjunctification

According to Uni in the USA, "One of the reasons American universities have thrived is due to their remarkable management of financial resources."[159] To combat costs colleges have hired adjunct professors to teach. In 2008 these teachers cost about $1,800 per 3-credit class as opposed to $8,000 per class for a tenured professor. Two-thirds of college instructors were adjuncts. There are differences of opinion whether these adjuncts teach better or worse than regular professors. There is a suspicion that student evaluation of adjuncts, along with their subsequent continued employment, can lead to grade inflation.[160]

Credential inflation

Economics professor Alan Zagier blames credential inflation for the admission of so many unqualified students into college. He reports that the number of new jobs requiring college degrees is less than the number of college graduates.[60] He states that the more money that a state spends on higher education, the slower the economy grows, the opposite of long held notions.[60] Other studies have shown that the level of cognitive achievement attained by students in a country (as measured by academic testing) is closely correlated with the country's economic growth, but that "increasing the average number of years of schooling attained by the labor force boosts the economy only when increased levels of school attainment also boost cognitive skills. In other words, it is not enough simply to spend more time in school; something has to be learned there."[161]

Governance and funding

Governance

Currently, the state and national governments share power over public education, with the states exercising most of the control. Except for Hawaii, states delegate power to county, city or township-level school boards that exercise control over a school district. Some school districts may further delegate significant authority to principals, such as those who have adopted the Portfolio strategy.

The U.S. federal government exercises its control through the U.S. Department of Education. Education is not mentioned in the constitution of the United States, but the federal government uses the threat of decreased funding to enforce laws pertaining to education.[127] Under recent administrations, initiatives such as the No Child Left Behind Act and Race to the Top have attempted to assert more central control in a heavily decentralized system.

Nonprofit private schools are widespread, are largely independent of the government, and include secular as well as parochial schools. Educational accreditation decisions for private schools are made by voluntary regional associations.

Funding for K–12 schools

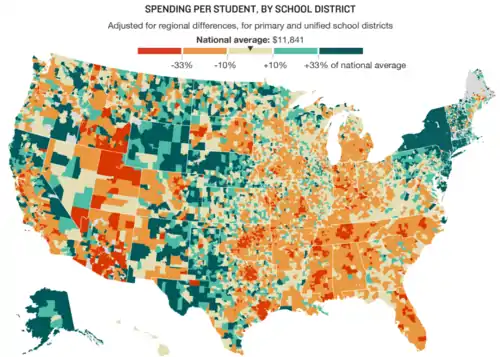

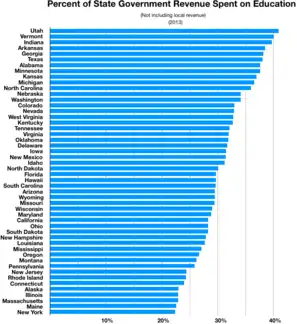

According to a 2005 report from the OECD, the United States is tied for first place with Switzerland when it comes to annual spending per student on its public schools, with each of those two countries spending more than $11,000.[162] However, the United States is ranked 37th in the world in education spending as a percentage of gross domestic product. All but seven of the leading countries are developing countries; ranked high because of a low GDP.[163]

Figures exist for education spending in the United States, both total and per student, and by state and school district. They show a very wide range in spending, but due to the varying spending policies and circumstances among school districts, a cost-effectiveness analysis is very difficult to perform.[164][165][166][167]

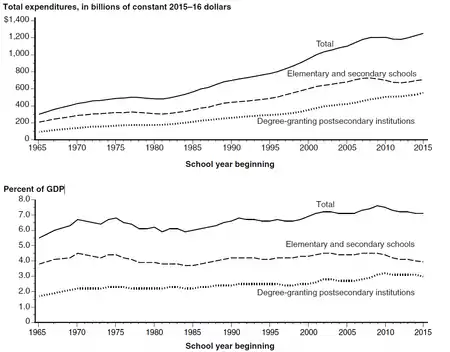

Changes in funding appear to have little effect on a school system's performance. Between 1970 and 2012, the full amount spent by all levels of government on the K–12 education of an individual public school student graduating in any given year, adjusted for inflation, increased by 185%. The average funding by state governments increased by 120% per student. However, scores in mathematics, science and language arts over that same period remained almost unchanged. Multi-year periods in which a state's funding per student declined substantially also appear to have had little effect.[168]

Property taxes as a primary source of funding for public education have become highly controversial, for a number of reasons. First, if a state's population and land values escalate rapidly, many longtime residents may find themselves paying property taxes much higher than anticipated. In response to this phenomenon, California's citizens passed Proposition 13 in 1978, which severely restricted the ability of the Legislature to expand the state's educational system to keep up with growth. Some states, such as Michigan, have investigated or implemented alternative schemes for funding education that may sidestep the problems of funding based mainly on property taxes by providing funding based on sales or income tax. These schemes also have failings, negatively impacting funding in a slow economy.[169]

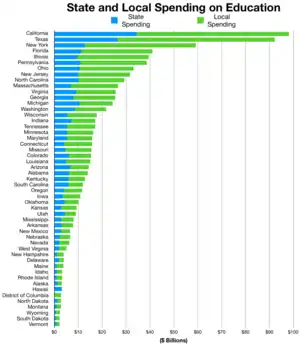

One of the biggest debates in funding public schools is funding by local taxes or state taxes. The federal government supplies around 8.5% of the public school system funds, according to a 2005 report by the National Center for Education Statistics.[170] The remaining split between state and local governments averages 48.7 percent from states and 42.8 percent from local sources.[170]

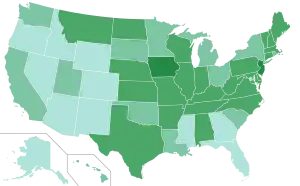

Rural schools struggle with funding concerns. State funding sources often favor wealthier districts. The state establishes a minimum flat amount deemed "adequate" to educate a child based on equalized assessed value of property taxes. This favors wealthier districts with a much larger tax base. This, combined with the history of slow payment in the state, leaves rural districts searching for funds. Lack of funding leads to limited resources for teachers. Resources that directly relate to funding include access to high-speed internet, online learning programs and advanced course offerings.[103] These resources can enhance a student's learning opportunities, but may not be available to everyone if a district cannot afford to offer specific programs. One study found that school districts spend less efficiently in areas in which they face little or no competition from other public schools, in large districts, and in areas in which residents are poor or less educated.[171] Some public schools are experimenting with recruiting teachers from developing countries in order to fill the teacher shortage, as U.S. citizens with college degrees are turning away from the demanding, low paid profession.[172]

Judicial intervention