Lands of Blacklaw

The Lands of Blacklaw formed a small property of five merks worth, in the Lordship of Stewarton at the eastern extremity of Strathannick, between the hamlet of Kingsford in East Ayrshire and the East Renfrewshire boundary, Scotland. It was first recorded in 1484 in the Acta Auditorum.[1] Black Law is a prominent whinstone crag lying above Blacklaw Hill Farm.[2]

Lands of Blacklaw

| |

|---|---|

Blacklaw Mound or Motte | |

Lands of Blacklaw Location within East Ayrshire | |

| OS grid reference | NS466496 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Glasgow |

| Postcode district | Neilston |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

History

The Estate and farms

Timothy Pont described the property in the early 17th century as "A pretty extensive range of land, now divided into several farms bearing the names of "Blacklaw", one of which is distinguished as Blacklaw-hill. It is situated in the north-east extremity of the parish of Stewarton, on the confines of Renfrewshire."[1]

A prominent feature is described as "On the farm called Blacklaw-hill is a mount, or small hill, of a conical shape, covered with a beautiful verdure, at the base of which are to be found some fine old trees, indicating the site of a Mansion in former times."[1]

In 1820 the lands of Whitelaw and Blacklaw amounted to 700 acres and the proprietors "live also together in townships".[3] The valued rent of the three properties at Blacklaw were William Gray at £62; John Brown at £62 and Thomas Wallace at £52.[4]

Black Law has had a number of whinstone quarries for local use, such as the steadings, drystone dykes and the Old Blacklaw Bridge. A track led up from Blacklaw Hill Farm to the site.[2]

Laird's house

A prominent feature is described by Timothy Pont in the early 17th century "On the farm called Blacklaw-hill is a mount, or small hill, of a conical shape, covered with a beautiful verdure, at the base of which are to be found some fine old trees, indicating the site of a Mansion in former times."[1] The small conical hill remains in situ, much as described here. Given the early seventeenth century date of Pont's survey any previous mansion house would date from the time where buildings would have some form of defensive fortification as in a typical Scottish tower castle. The site was once surrounded by a drystone dyke, possibly recycling stone from an old building, to exclude grazing animals and a few old beech trees remain.

The conical hill is not listed as a site of archaeological interest and appears never to have been surveyed or excavated, so no information exists as to whether it is entirely natural and if it was used as a motte, a defensive site of some sort or as a Moot Hill, Court Hill or Gallows Hill. The Lands of Blacklaw were part of the Lordship of Stewarton in 1484[1] and in 1685 the lands are referred to as a 'Lairdship',[5] defined as "A barony or lordship; from an early date, the estate or territory under the jurisdiction of a laird or small baron or freeholder."[6] A Laird's dwelling would have been one of the Blacklaw dwellings. The lands passed into the hands of the Cunninghames of Corshill until they were granted to John Brown in Gabrochhill in 1687.[7]

Old Blacklaw Bridge

The Annick Water lies to the south of the lands of Blacklaw with a bridge (NS465494) carrying a datestone on the upstream side with the initials 'I.Brown' and the dates 1770 and 1881 implying construction and later renovation although the style, execution and weathering of the carving on soft sandstone suggests that the dates, etc. are contemporary with each other and therefore the actual carving is no older than 1818. The 'I' stands for Iohannes which is now written as 'John' and the surname indicated the Brown family, originally of Gabrochhill where they had resided for many generations.[1] The date '1770' has an odd first numeral shaped almost as a 'J'. The bridge is constructed of whinstone, wide enough for horse-drawn vehicles and has mostly lost its low side walls. The datestone is not located as a keystone on the arch of the bridge and therefore could have been inserted at any time, in addition, as stated, it is made of red sandstone.

The head waters of the Annick Water are comparatively shallow and, even in winter, a ford might have sufficed. Blacklaw farm tenants are shown to have had fields here as indicated by the field boundaries marked on Roy's map of 1747[8] and a track leads up on to Glenouther Moor[2] where the common grazings were located and peats may have been dug. The same map shows a sheep ree on a field boundary, used as a permanent stone sheep-pen where sheep could be confined during poor weather, for shearing, etc.

The Blacklaw Lairds, tenants, etc.

In 1484 the tak of the three merks worth lands of Cockilbie and the five merks worth lands of Blacklaw were in dispute and a special writ by the king awarded the tak to "Dauid Lindissa and his spous the wif of umquhile Jenkin Stewart".[1] David Lindsay's dispute was with John Ross of Montgreenan.[9]

The 10 merk land of Blacklaw and Blacklawhill passed into the hands of the Cunninghames of Corshill and on 23 September 1687 Sir Alexander Cuninghame and his mother, Lady Corshill, Dame Mary Stewart, granted a charter of the 2.5 merk land of Blacklawhill to John Brown in Gabrochill (sic). Dobie comments that all the eldest sons were called John, not commonplace outside of the aristocracy.[7]

This John married Elizabeth Brown and had five offspring, John, the eldest. inheriting and marrying Jean Allison of Milton, East Kilbride and having four offspring.[1] Their eldest son John inherited and married Janet Cuthbertson of Carswell, Neilston. They had seven offspring and the eldest, John, inherited in 1750, marrying Grizel Mitchel of Langreen, Loudoun parish. In 1778 their only son John inherited, marrying Elizabeth Deans of Peacockbank and having six children, followed by a second marriage to Margaret Gray of Irvine and the couple having three children. John, the eldest, inherited in 1846 and married Mary Kerr of Stewarton. The couple had offspring, John, William, Andrew, James and four daughters.[7]

In 1747 Jean, only daughter of John Brown of Blacklawhill married William Mackie of Fulwood and Easter-house of Corshill.[10]

John Brown of Gabrochhill's only daughter, Mary, married Mathew Arnot Stewart, representing the Stewarts of Newton and the Arnots of Lochridge. He died in 1796 and his son Mathew (sic) succeeded him.[11]

The court book of the Barony of Corshill and Cocklbee in 1666 lists the occupiers of the Lands of Blacklaw as William Fultoune (thair); Alexander Fultoune; Alexander Thomsoune; Robert Faullis; Robert Walker; James Faullis and Robert Waker.[12]

In May 1685 the tenants of the lairdship beneath the Black Law were pursued by the Barony Court for "cutting of young root grown trees within the parkes of Corshill"[5]

In December 1701 John Brown and Robert Faullis of Blacklaw were requested by the Barony Court judge to assess how many swine could be grazed on the common pasturage of Hareshaw and Corshouse. They were to assess also which of the two farmers involved suffered most by the overgrazing by the other.[13]

In May 1707 Sir Alexander Cunninghame of Corshill claimed against Janet Thomsone, John Brown and Andrew Faullis of Blacklaw at the Barony court for continuing to eat and destroy "the wast grassis of the maillen of Blacklaw". They were instructed to cease eating "the said wast grass with bestial, goodes, and gear" immediately and informed that the "bestial, goodes, and gear" would be "poyndit", that is confiscated and possibly sold if found breaking this sentence of the court. Despite being warned and informed the defenders did not attend the court held in Stewarton.[14]

The Ayrshire Ordnance Survey name book of 1855 to 1857 records Midtown of Blacklaw as a" farmhouse with outbuildings garden etc. the property of Dr. Brown Stewarton; Townhead of Blacklaw as a "farmhouse with outbuildings garden - the property of Allen Brown Esqr. Brom"; Lowtown of Blacklaw as a "farmhouse with extensive outbuildings etc. The property of Mr. Thomas Wallace - Stewarton" and Blacklawhall aka Blacklawhill as a "neat farmhouse with very extensive outbuildings, the property of the Occupier Mr. J. Brown."[15]

The Moor of Machirnock (Glenouther)

This was a very large and valuable area of common grazing immediately to the south of Blacklaw, then known as Machirnock or Maucharnock,[16] now known as Glenouther Moor. The Cunningham and Mure families were often in dispute over their rights regarding grazing, etc. and a royal letter of 1534 states that the Cunninghams had not been invested in the moor and it was decided that the souming was split between Polkelly and Rowallan. [17]

The souming was the number or proportion of cattle which each tenant was entitled to keep on the common grazing.[18] In 1594 William Mure of Rowallan complained of the excess of Polkelly's grazing cattle and geese on the moor, despite having obtained a caution of lawburrows on May 20, 1593. Lawburrows was a letter in the monarch's name under the signet seal to the effect that a particular person had shown cause to dread harm from another, and that therefore this other complained of was commanded to find "sufficient caution and surety" that the complainer would be free from any violence on his part.[19]

The Barony Court records show that some local farms had access to the common grazing and that may have included the Blacklaw farms.[13]

The Robertland Estate was put up for sale in 1913, consisting of 2,243 acres (9.08 km2), with 71 acres (290,000 m2) as woodland and 168 acres (0.68 km2) as moss, 26 farms were present and shooting rights were held for Glenouther Moor. The moor is now mainly afforested with pine trees.

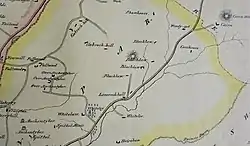

Cartographic evidence

Roy's map of 1747 shows a well laid out grouping of three dwellings below Blacklaw Hill and Blacklaw Townhead above to the north-east. Corshouse and Hareshaw farms lay on the Glenouther Moor side of the Annick Water.[8] In 1856 Blacklawhill, Lowtown of Blacklaw and Midtown of Blacklaw are shown with Townhead of Blacklaw to the north-east. A Blacklaw Cottage stands on the driveway to Blacklawhill.[20] In 1895 a track ran up to the Glenouther Moor crossing the Annock Water by a bridge. A sheep ree is shown on a field boundary below the moor edge.[2]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black Law Motte. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old Blacklaw Bridge. |

References

- Notes

- Dobie, James (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. John Tweed. p. 99.

- Renfrewshire XVIII.6, Revised: 1895, Published: 1897

- Robertson, George (1820). Topographical Description of Ayrshire more particularly in Cunninghame. Cunninghame Press. p. 324.

- Robertson, George (1820). Topographical Description of Ayrshire more particularly in Cunninghame. Cunninghame Press. p. 327.

- Shedden-Dobie, John (1884). Corshill Baron-Court Book. Vol. iv. Ayr and Wigton Archaeological Association. p. 169.

- Dictionary of Scots

- Dobie, James (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. John Tweed. p. 100.

- Roy Lowlands 1752-55

- Dobie, James (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. John Tweed. p. 333.

- Dobie, James (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. John Tweed. p. 138.

- Robertson, George (1823). A Genealogical Account of the Principal Families in Ayrshire more particularly of Cunninghame. Cunninghame Press. p. 21.

- Shedden-Dobie, John (1884). Corshill Baron-Court Book. Vol. iv. Ayr and Wigton Archaeological Association. p. 68.

- Shedden-Dobie, John (1884). Corshill Baron-Court Book. Vol. iv. Ayr and Wigton Archaeological Association. p. 186.

- Shedden-Dobie, John (1884). Corshill Baron-Court Book. Vol. iv. Ayr and Wigton Archaeological Association. p. 226.

- Ayr Ordnance Survey Name Book. 1855-1857.

- Moll, Herman, d. 1732. The Shire of Renfrew with Cuningham [i.e. Cunningham]. The North Part of Air [i.e. Ayr] / by H. Moll.

- Ewart, Gordon (2009). A Palace fit for a Laird. Rowallan Castle. Archaeological and Research 1998-2008. Historic Scotland. Historic Scotland. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-84917-015-4.

- Researcher's Guide Retrieved : 2011-06-10

- Researcher;s Guide Retrieved : 2011-06-10

- Renfrewshire, Sheet XVIII, Surveyed: 1856, Published: 1863

- Sources and Bibliography

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to Ayr & Wigton. 1884. Vol. IV. Shedden-Dobie, John. The Church of Dunlop.

- Davis, Michael C. (1991). The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire. Privately Published.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed.

- Fullarton, John (1864). Historical Memoir of the family of Eglinton and Winton. Ardrossan : Arthur Guthrie.

- Johnston, J. B. (1903). Place-names of Scotland. Edinburgh : David Douglas.

- Mackenzie, W. Mackay (1927). The Medieval Castle in Scotland. Pub. Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- MacIntosh, John (1894). Ayrshire Nights Entertainments: A Descriptive Guide to the History, Traditions, Antiquities, etc. of the County of Ayr. Pub. Kilmarnock.

- McMichael, George (c. 1881 - 1890). Notes on the Way Through Ayrshire and the Land of Burn, Wallace, Henry the Minstrel, and Covenant Martyrs. Hugh Henry : Ayr.

- Ness, John (1990). Kilwinning Encyclopedia. Kilwinning & District Preservation Society.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. - IV - Cunninghame. Part 1. Edinburgh : J. Stillie.