Latinisation in the Soviet Union

In the USSR, latinisation or latinization (Russian: латиниза́ция, latinizatsiya) was the name of the campaign during the 1920s–1930s which aimed to replace traditional writing systems for all languages of the Soviet Union with systems that would use the Latin script or to create Latin-script-based systems for languages that, at the time, did not have a writing system.

History

Background

Since at least 1700, Russian intellectuals have sought to Latinise the Russian language in their desire for close relations with the West.[1]

The early 20th-century Bolsheviks had four goals: to break with Tsarism, to spread socialism to the whole world, to isolate the Muslim inhabitants of the Soviet Union from the Arabic-Islamic world and religion, and eradicate illiteracy through simplification.[1] They concluded the Latin alphabet was the right tool to do so, and after seizing power during the Russian Revolution of 1917, they made plans to realise these ideals.[1] Although progress was slow at first, in 1926 the Turkic-majority republics of the Soviet Union adopted the Latin script, giving a major boost to reformers in neighbouring Turkey.[2] When Mustafa Kemal Atatürk adopted the new Turkish Latin alphabet in 1928, this in turn encouraged the Soviet leaders to proceed.[1]

Procedure

Almost all Turkic, Iranian, Uralic and several other languages were romanised, totaling nearly 50 of the 72 written languages in the USSR. There also existed plans to romanise Russian and other Slavic languages as well, but in the late 1930s the latinisation campaign was cancelled and all newly romanised languages were converted to Cyrillic.

In 1929 the People's Commissariat of the RSFSR formed a committee to develop the question of the romanisation of the Russian alphabet, led by Professor N. F. Yakovlev and with the participation of linguists, bibliographer, printers, and engineers. The Commission completed its work in mid-January 1930. However, on 25 January 1930, General Secretary Joseph Stalin ordered to halt the development of the question of the romanisation of the Cyrillic alphabet for the Russian language.[1]

The following languages were romanised or adapted new Latin-script alphabets:[3]

- Abaza (1932)

- Abkhaz (Abkhaz alphabet) (1924)

- Adyghe (1926)

- Altai (1929)

- Assyrian (1930)

- Avar (1928)

- Azerbaijani (Azerbaijani alphabet) (1922)

- Balochi (Balochi Latin) (1933)

- Bashkir (1927)

- Bukhori (1929)

- Buryat (1929)

- Chechen (1925)

- Chinese (Latinxua Sin Wenz) (1931)

- Chukchi (Chucki Latin) (1931)

- Crimean Tatar (First Latin) (1927)

- Dargin (1928)

- Dungan (1928)

- Eskimo (1931)

- Even (1931)

- Evenki (Evenki Latin) (1931)

- Ingrian (Ingrian alphabet) (1932)

- Ingush (1923)

- Itelmen (1931)

- Kabardiano-Cherkess (1923)

- Kalmyk (1930)

- Karachay-Balkar (1924)

- Karaim (1928)

- Karakalpak (1928)

- Karelian (Karelian alphabet) (1931)

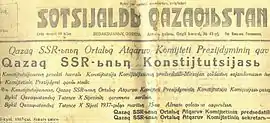

- Kazakh (Kazakh alphabet) (1928)

- Ket (1931)

- Khakas (1929)

- Khanty (1931)

- Komi (1932)

- Komi-Permyak (1932)

- Koryak (1931)

- Krymchak (1928)

- Kumandin (1932)

- Kumyk (1927)

- Kurdish (Kurdish alphabets) (1929)

- Kyrgyz (Kyrgyz alphabets) (1928)

- Lak (1928)

- Laz (1930)

- Lezgin (Lezgin alphabets) (1928)

- Mansi (1931)

- Moldovan (Moldovan alphabet) (1928)

- Nanai language (1931)

- Nenets languages (1931)

- Nivkh language (1931)

- Nogai language (1928)

- Ossetic language (1923)

- Persian alphabet (1930)

- Sami language (1931)

- Selkup language (1931)

- Shor language (1931)

- Shughni language (1932)

- Yakut (1920)

- Tabasaran language (1932)

- Tajik alphabet (1928)

- Talysh language (1929)

- Tat language (1933)

- Tatar language (Yañalif) (1928)

- Tsakhur language (1934)

- Turkmen alphabet (1929)

- Udege language (1931)

- Udi language (1934)

- Uyghur language (1928)

- Uzbek language (1927)

- Vepsian language (1932)

Projects were created and approved for the following languages:

- Aleut language

- Arabic language

- Korean language

- Udmurt language

But they have not been implemented. Projects were developed for the romanization of all other alphabets of the peoples of the USSR.

On August 8, 1929, by the decree of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR "On the new Latinized alphabet of the peoples of the Arabic written language of the USSR" the transition to the Latin alphabet was given an official status. The transition to a new alphabet of newspapers and magazines, publishing houses, educational institutions began. Since 1930, a new stage of romanization begins: the transition to a new alphabet of peoples of other language groups.

In total, between 1923 and 1939, alphabets for 50 languages (out of 72 languages of the USSR that had a written language) were created on the basis of the Latin alphabet. In the Mari, Mordovian and Udmurt languages, the use of the Cyrillic alphabet continued even during the period of maximum Latinization.[4]

However, in 1936, a new campaign began - to translate all the languages of the peoples of the USSR into Cyrillic, which was basically completed by 1940 (German, Georgian, Armenian and Yiddish remained non-cyrillized from the languages common in the USSR, the last three were also not Latinized). Later, Polish, Finnish, Latvian, Estonian and Lithuanian languages also remained uncyrillized.

See also

References

- Andresen, Julie Tetel; Carter, Phillip M. (2016). Languages In The World: How History, Culture, and Politics Shape Language. John Wiley & Sons. p. 110. ISBN 9781118531280. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Zürcher, Erik Jan. Turkey: a modern history, p. 188. I.B.Tauris, 2004. ISBN 978-1-85043-399-6

- Алфавит Октября. Итоги введения нового алфавита среди народов РСФСР. М. 1934. pp. 156–160.

- Алпатов В. М. (2000). 150 языков и политика. 1917—2000. Социолингвистические проблемы СССР и постсоветского пространства. М. p. 70.