Uyghur language

The Uyghur or Uighur language (/ˈwiːɡər/;[3][4] ئۇيغۇر تىلى, Уйғур тили, Uyghur tili, Uyƣur tili, IPA: [ujɣur tili] or ئۇيغۇرچە, Уйғурчә, Uyghurche, Uyƣurqə, IPA: [ujɣurˈtʃɛ], CTA: Uyğurçä; formerly known as Eastern Turki), is a Turkic language, written in a Uyghur Perso-Arabic script, with 10 to 15 million speakers,[5][6] spoken primarily by the Uyghur people in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Western China. Significant communities of Uyghur speakers are located in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan and various other countries have Uyghur-speaking expatriate communities. Uyghur is an official language of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and is widely used in both social and official spheres, as well as in print, television and radio and is used as a common language by other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.[7]

| Uyghur | |

|---|---|

| Uighur | |

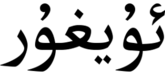

| ئۇيغۇر تىلى, Уйғур тили, Uyghur tili, Uyƣur tili, Uyğur tili | |

Uyghur written in Perso-Arabic script | |

| Pronunciation | [ʊjʁʊrˈtʃɛ], [ʊjˈʁʊr tili] |

| Native to | Xinjiang |

| Ethnicity | Uyghur |

Native speakers | ~10 million (2015)[1] |

Turkic

| |

Early forms | Karakhanid

|

| Uyghur alphabets (Uyghur Perso-Arabic alphabet (official), Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet, Uyghur Latin alphabet, Uyghur New Script) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Working Committee of Ethnic Language and Writing of Xinjiang |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ug Uighur, Uyghur |

| ISO 639-2 | uig Uighur, Uyghur |

| ISO 639-3 | uig Uighur, Uyghur |

| Glottolog | uigh1240 Uighur |

Geographical extent of Uyghur in China | |

Uyghur belongs to the Karluk branch of the Turkic language family, which also includes languages such as Uzbek. Like many other Turkic languages, Uyghur displays vowel harmony and agglutination, lacks noun classes or grammatical gender and is a left-branching language with subject–object–verb word order. More distinctly Uyghur processes include, especially in northern dialects, vowel reduction and umlauting. In addition to influence of other Turkic languages, Uyghur has historically been influenced strongly by Arabic and Persian and more recently by Russian and Mandarin Chinese.

The modified Arabic-derived writing system is the most common and the only standard in China,[8] although other writing systems are used for auxiliary and historical purposes. Unlike most Arabic-derived scripts, the Uyghur Arabic alphabet has mandatory marking of all vowels due to modifications to the original Perso-Arabic script made in the 20th century. Two Latin and one Cyrillic alphabet are also used, though to a much lesser extent. The Latin alphabets have 32 characters, while Arabic has 28. Arabic alphabets are used in Persian with the addition of four more characters. Hence, the Persian alphabet has 32 characters.

History

The Middle Turkic languages are the direct ancestor of the Karluk languages, including Uyghur and the Uzbek language.

Modern Uyghur is not descended from Old Uyghur, rather, it is a descendant of the Karluk language spoken by the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[9] According to Gerard Clauson, Western Yugur is considered to be the true descendant of Old Uyghur and is also called "Neo-Uyghur". Modern Uyghur is not a descendant of Old Uyghur, but is descended from the Khaqani language described by Mahmud al-Kashgari in Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk.[10] According to Frederik Coene, Modern Uyghur and Western Yugur belong to entirely different branches of the Turkic language family, respectively the Southeastern Turkic languages and the Northeastern Turkic languages.[11][12] The Western Yugur language, although in geographic proximity, is more closely related to the Siberian Turkic languages in Siberia.[13] Robert Dankoff wrote that the Turkic language spoken in Kashgar and used in Kara Khanid works was Karluk, not (Old) Uyghur.[14]

Robert Barkley Shaw wrote, "In the Turkish of Káshghar and Yarkand (which some European linguists have called Uïghur, a name unknown to the inhabitants of those towns, who know their tongue simply as Túrki), ... This would seem in many case to be a misnomer as applied to the modem language of Kashghar".[15] Sven Hedin wrote, "In these cases it would be particularly inappropriate to normalize to the East Turkish literary language, because by so doing one would obliterate traces of national elements which have no immediate connection with the Kaschgar Turks, but on the contrary are possibly derived from the ancient Uigurs".[16]

Probably around 1077,[17] a scholar of the Turkic languages, Mahmud al-Kashgari from Kashgar in modern-day Xinjiang, published a Turkic language dictionary and description of the geographic distribution of many Turkic languages, Dīwān ul-Lughat al-Turk (English: Compendium of the Turkic Dialects; Uyghur: تۈركى تىللار دىۋانى, Türki Tillar Diwani). The book, described by scholars as an "extraordinary work,"[18][19] documents the rich literary tradition of Turkic languages; it contains folk tales (including descriptions of the functions of shamans)[19] and didactic poetry (propounding "moral standards and good behaviour"), besides poems and poetry cycles on topics such as hunting and love[20] and numerous other language materials.[21] Other Kara-Khanid writers wrote works in the Turki Karluk Khaqani language. Yusuf Khass Hajib wrote the Kutadgu Bilig. Ahmad bin Mahmud Yukenaki (Ahmed bin Mahmud Yükneki) (Ahmet ibn Mahmut Yükneki) (Yazan Edib Ahmed b. Mahmud Yükneki) (w:tr:Edip Ahmet Yükneki) wrote the Hibat al-ḥaqāyiq (هبة الحقايق) (Hibet-ül hakayik) (Hibet ül-hakayık) (Hibbetü'l-Hakaik) (Atebetüʼl-hakayik) (w:tr:Atabetü'l-Hakayık).

Middle Turkic languages, through the influence of Perso-Arabic after the 13th century, developed into the Chagatai language, a literary language used all across Central Asia until the early 20th century. After Chaghatai fell into extinction, the standard versions of Uyghur and Uzbek were developed from dialects in the Chagatai-speaking region, showing abundant Chaghatai influence. Uyghur language today shows considerable Persian influence as a result from Chagatai, including numerous Persian loanwords.[22]

Modern Uyghur religious literature includes the Taẕkirah, biographies of Islamic religious figures and saints. The Taẕkirah is a genre of literature written about Sufi Muslim saints in Altishahr. Written sometime in the period between 1700 and 1849, the Chagatai language (modern Uyghur) Taẕkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams provides an account of the Muslim Karakhanid war against the Khotanese Buddhists, containing a story about Imams, from Mada'in city (possibly in modern-day Iraq) came 4 Imams who travelled to help the Islamic conquest of Khotan, Yarkand and Kashgar by Yusuf Qadir Khan, the Qarakhanid leader.[23] The shrines of Sufi Saints are revered in Altishahr as one of Islam's essential components and the tazkirah literature reinforced the sacredness of the shrines. Anyone who does not believe in the stories of the saints is guaranteed hellfire by the tazkirahs. It is written, "And those who doubt Their Holinesses the Imams will leave this world without faith and on Judgement Day their faces will be black ..." in the Tazkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams.[24] Shaw translated extracts from the Tazkiratu'l-Bughra on the Muslim Turki war against the "infidel" Khotan.[25] The Turki-language Tadhkirah i Khwajagan was written by M. Sadiq Kashghari.[26] Historical works like the Tārīkh-i amniyya and Tārīkh-i ḥamīdi were written by Musa Sayrami.

The Qing dynasty commissioned dictionaries on the major languages of China which included Chagatai Turki language, such as the Pentaglot Dictionary.

Shaw and Christian missionaries such as George W. Hunter, Johannes Avetaranian, Magnus Bäcklund, Nils Fredrik Höijer, Father Hendricks, Josef Mässrur, Anna Mässrur, Albert Andersson, Gustaf Ahlbert, Stina Mårtensson, John Törnquist, Gösta Raquette, Oskar Hermannson, the convert to Christianity Nur Luke, Harold Whitaker and Turkologist Gunnar Jarring studied the Uyghur language and wrote works on it, calling it "Eastern Turki". Shaw wrote in his book that it was Europeans at his time who called the language "Uighur" while the native inhabitants of Yarkand and Kashgar did not call it by that name and but called it "Turki" and Shaw wrote that the name "Uighur" was a misnomer when referring to Kashgar's language. A Turkish convert to Christianity, Johannes Avetaranian went to China to spread Christianity to the Uyghurs. Yaqup Istipan, Wu'erkaixi and Alimujiang Yimiti are other Uyghurs who converted to Christianity.

The Bible was translated into the Kashgari dialect of Turki (Uyghur).[27]

The historical term "Uyghur" was appropriated for the language that had been known as Eastern Turki by government officials in the Soviet Union in 1922 and in Xinjiang in 1934.[28][29] Sergey Malov was behind the idea of renaming Turki to Uyghurs.[30] The use of the term Uyghur has led to anachronisms when describing the history of the people.[31] In one of his books the term Uyghur was deliberately not used by James Millward.[32] The name Khāqāniyya was given to the Qarluks who inhabited Kāshghar and Bālāsāghūn, the inhabitants were not Uighur, but their language has been retroactively labelled as Uighur by scholars.[14] The Qarakhanids called their own language the "Turk" or "Kashgar" language and did not use Uighur to describe their own language, Uighur was used to describe the language of non-Muslims but Chinese scholars have anachronistically called a Qarakhanid work written by Kashgari as "Uighur".[33] The name "Altishahri-Jungharian Uyghur" was used by the Soviet educated Uyghur Qadir Haji in 1927.[34]

Classification

The Uyghur language belongs to the Karluk Turkic (Qarluq) branch of the Turkic language family. It is closely related to Äynu, Lop, Ili Turki, the extinct language Chagatay (the East Karluk languages), and more distantly to Uzbek (which is West Karluk).

Early linguistic scholarly studies of Uyghur include Julius Klaproth's 1812 Dissertation on language and script of the Uighurs (Abhandlung über die Sprache und Schrift der Uiguren) which was disputed by Isaak Jakob Schmidt. In this period, Klaproth correctly asserted that Uyghur was a Turkic language, while Schmidt believed that Uyghur should be classified with Tangut languages.[35]

Dialects

It is widely accepted that Uyghur has three main dialects, all based on their geographical distribution. Each of these main dialects have a number of sub-dialects which all are mutually intelligible to some extent.

- Central: Spoken in an area stretching from Kumul towards south to Yarkand

- Southern: Spoken in an area stretching from Guma towards east to Qarkilik

- Eastern: Spoken in an area stretching from Qarkilik towards north to Qongköl. The Lopnor Uighur dialect (also known as Lopluk) that falls under the Eastern dialect of the Uighur language is classified as a critically endangered language.[36] It is spoken by less than 0.5% of the overall Uighur speakers population but has tremendous values in comparative research.

The Central dialects are spoken by 90% of the Uyghur-speaking population, while the two other branches of dialects only are spoken by a relatively small minority.[37]

Vowel reduction is common in the northern parts of where Uyghur is spoken, but not in the south.[38]

Status

Uyghur is spoken by about 10 million people in total.[39][5][6] In addition to being spoken primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Western China, mainly by the Uyghur people, Uyghur was also spoken by some 300,000 people in Kazakhstan in 1993, some 90,000 in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan in 1998, 3,000 in Afghanistan and 1,000 in Mongolia, both in 1982.[39] Smaller communities also exist in Albania, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Indonesia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Turkey, United Kingdom and the United States (New York City).[5]

The Uyghurs are one of the 56 recognized ethnic groups in China and Uyghur is an official language of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, along with Standard Chinese. As a result, Uyghur can be heard in most social domains in Xinjiang and also in schools, government and courts.[39] Of the other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, those populous enough to have their own autonomous prefectures, such as the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz, have access to schools and government services in their native language. Smaller minorities, however, do not have a choice and must attend Uyghur-medium schools.[40] These include the Xibe, Tajiks, Daurs and Russians.[41] In some instances Uyghur parents decide to enroll their children at Mandarin schools over Uyghur schools because of the better quality education offered, leading to many Uyghur children having more trouble learning their native language over Mandarin.[42] However, according to Radio Free Asia, Xinjiang's Hotan government have issued a directive completely banning the use of the Uyghur language at all education levels up to and including secondary school in 2017.[43] According to reports in 2018, Uyghur script was erased from street signs and wall murals, as Chinese government has launched a campaign to force Uyghur people to learn Mandarin. Any interest in Uyghur culture or language could lead to detention.[44][45] Recent news reports have also documented the existence of mandatory boarding schools where children are separated from their parents; children are punished for speaking Uyghur, making the language at a very high risk of extinction.[46]

According to report of Financial Times in 2019, the only Uighur-language book available in Xinjiang's state-run Xinhua Bookstores was Xi Jinping's The Governance of China. In Kashgar, the traditional capital of Uighur culture, there were five independent Uighur-language bookstores, only selling novels, cookery or self-help books.[47] In addition, the Chinese government have implemented bi-lingual education in most regions of Xinjiang.[48] The bi-lingual education system teaches Xinjiang's students all STEM classes using only Mandarin Chinese, or a combination of Uighur and Chinese. However, research have shown that due to differences in the order of words and grammar between the Uighur and the Chinese language, many students face obstacles in learning courses such as Mathematics under the bi-lingual education system.[49]

Uyghur language has been supported by Google Translate since February 2020.[50][51]

About 80 newspapers and magazines are available in Uyghur; five TV channels and ten publishers serve as the Uyghur media. Outside of China, Radio Free Asia provides news in Uyghur.

The poet Muyesser Abdul'ehed teaches the language to diaspora children online as well as publishing a magazine written by children for children in Uyghur.[52]

Phonology

Vowels

The vowels of the Uyghur language are, in their alphabetical order (in the Latin script), ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨ë⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩. There are no diphthongs. Hiatus occurs in some loanwords.

Uyghur vowels are distinguished on the bases of height, backness and roundness. It has been argued, within a lexical phonology framework, that /e/ has a back counterpart /ɤ/, and modern Uyghur lacks a clear differentiation between /i/ and /ɯ/.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| Close | i, ɪ | y, ʏ | (ɨ), (ɯ) | ʊ, u |

| Mid | e | (ɤ) | o | |

| Open | ɛ, æ | œ | ʌ, ɑ | ɔ |

Uyghur vowels are by default short, but long vowels also exist because of historical vowel assimilation (above) and through loanwords. Underlyingly long vowels would resist vowel reduction and devoicing, introduce non-final stress, and be analyzed as |Vj| or |Vr| before a few suffixes. However, the conditions in which they are actually pronounced as distinct from their short counterparts have not been fully researched.[53]

The high vowels undergo some tensing when they occur adjacent to alveolars (s, z, r, l), palatals (j), dentals (t̪, d̪, n̪), and post-alveolar affricates (t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ), e.g. chiraq [t͡ʃʰˈiraq] 'lamp', jenubiy [d͡ʒɛnʊˈbiː] 'southern', yüz [jyz] 'face; hundred', suda [suːˈda] 'in/at (the) water'.

Both [i] and [ɯ] undergo apicalisation after alveodental continuants in unstressed syllables, e.g. siler [sɪ̯læː(r)] 'you (plural)', ziyan [zɪ̯ˈjɑːn] 'harm'. They are medialised after /χ/ or before /l/, e.g. til [tʰɨl] 'tongue', xizmet [χɨzˈmɛt] 'work; job; service'. After velars, uvulars and /f/ they are realised as [e], e.g. giram [ɡeˈrʌm] 'gram', xelqi [χɛlˈqʰe] 'his [etc.] nation', Finn [fen] 'Finn'. Between two syllables that contain a rounded back vowel each, they are realised as back, e.g. qolimu [qʰɔˈlɯmʊ] 'also his [etc.] arm'.

Any vowel undergoes laxing and backing when it occurs in uvular (/q/, /ʁ/, /χ/) and laryngeal (glottal) (/ɦ/, /ʔ/) environments, e.g. qiz [qʰɤz] 'girl', qëtiq [qʰɤˈtɯq] 'yogurt', qeghez [qʰæˈʁæz] 'paper', qum [qʰʊm] 'sand', qolay [qʰɔˈlʌɪ] 'convenient', qan [qʰɑn] 'blood', ëghiz [ʔeˈʁez] 'mouth', hisab [ɦɤˈsʌp] 'number', hës [ɦɤs] 'hunch', hemrah [ɦæmˈrʌh] 'partner', höl [ɦœɫ] 'wet', hujum [ɦuˈd͡ʒʊm] 'assault', halqa [ɦɑlˈqʰɑ] 'ring'.

Lowering tends to apply to the non-high vowels when a syllable-final liquid assimilates to them, e.g. kör [cʰøː] 'look!', boldi [bɔlˈdɪ] 'he [etc.] became', ders [dæːs] 'lesson', tar [tʰɑː(r)] 'narrow'.

Official Uyghur orthographies do not mark vowel length, and also do not distinguish between /ɪ/ (e.g., بىلىم /bɪlɪm/ 'knowledge') and back /ɯ/ (e.g., تىلىم /tɯlɯm/ 'my language'); these two sounds are in complementary distribution, but phonological analyses claim that they play a role in vowel harmony and are separate phonemes.[54] /e/ only occurs in words of non-Turkic origin and as the result of vowel raising.[55]

Uyghur has systematic vowel reduction (or vowel raising) as well as vowel harmony. Words usually agree in vowel backness, but compounds, loans, and some other exceptions often break vowel harmony. Suffixes surface with the rightmost [back] value in the stem, and /e, ɪ/ are transparent (as they do not contrast for backness). Uyghur also has rounding harmony.[56]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Post- alveolar/Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | dʒ | k | ɡ | q | ʔ | ||

| Fricative | (f) | (v) | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | χ | ʁ | ɦ | |||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||

Uyghur voiceless stops are aspirated word-initially and intervocalically.[57] The pairs /p, b/, /t, d/, /k, ɡ/, and /q, ʁ/ alternate, with the voiced member devoicing in syllable-final position, except in word-initial syllables. This devoicing process is usually reflected in the official orthography, but an exception has been recently made for certain Perso-Arabic loans.[58] Voiceless phonemes do not become voiced in standard Uyghur.[59]

Suffixes display a slightly different type of consonant alternation. The phonemes /ɡ/ and /ʁ/ anywhere in a suffix alternate as governed by vowel harmony, where /ɡ/ occurs with front vowels and /ʁ/ with back ones. Devoicing of a suffix-initial consonant can occur only in the cases of /d/ → [t], /ɡ/ → [k], and /ʁ/ → [q], when the preceding consonant is voiceless. Lastly, the rule that /g/ must occur with front vowels and /ʁ/ with back vowels can be broken when either [k] or [q] in suffix-initial position becomes assimilated by the other due to the preceding consonant being such.[60]

Loan phonemes have influenced Uyghur to various degrees. /d͡ʒ/ and /χ/ were borrowed from Arabic and have been nativized, while /ʒ/ from Persian less so. /f/ only exists in very recent Russian and Chinese loans, since Perso-Arabic (and older Russian and Chinese) /f/ became Uyghur /p/. Perso-Arabic loans have also made the contrast between /k, ɡ/ and /q, ʁ/ phonemic, as they occur as allophones in native words, the former set near front vowels and the latter near a back vowels. Some speakers of Uyghur distinguish /v/ from /w/ in Russian loans, but this is not represented in most orthographies. Other phonemes occur natively only in limited contexts, i.e. /h/ only in few interjections, /d/, /ɡ/, and /ʁ/ rarely initially, and /z/ only morpheme-final. Therefore, the pairs */t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/, */ʃ, ʒ/, and */s, z/ do not alternate.[61][62]

Phonotactics

The primary syllable structure of Uyghur is CV(C)(C).[5] Uyghur syllable structure is usually CV or CVC, but CVCC can also occur in some words. When syllable-coda clusters occur, CC tends to become CVC in some speakers especially if the first consonant is not a sonorant. In Uyghur, any consonant phoneme can occur as the syllable onset or coda, except for /ʔ/ which only occurs in the onset and /ŋ/, which never occurs word-initially. In general, Uyghur phonology tends to simplify phonemic consonant clusters by means of elision and epenthesis.[63]

Orthography

The Karluk language started to be written with the Perso-Arabic script (Kona Yëziq) in the 10th century upon the conversion of the Kara-Khanids to Islam. This Perso-Arabic script (Kona Yëziq) was reformed in the 20th century with modifications to represent all Modern Uyghur sounds including short vowels and eliminate Arabic letters representing sounds not found in Modern Uyghur. Unlike many other modern Turkic languages, Uyghur is primarily written using an Arabic alphabet, (with 4 alphabets like che-Pe-Zhe and Ga) although a Cyrillic alphabet and two Latin alphabets also are in use to a much lesser extent. Unusually for an alphabet based on the Persian, full transcription of vowels is indicated. (Among the Arabic family of alphabets, only a few, such as Kurdish, distinguish all vowels without the use of optional diacritics.)

The four alphabets in use today can be seen below.

- Uyghur Arabic alphabet or UEY

- Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet or USY

- The Uyghur New Script or UYY

- Uyghur Latin alphabet or ULY

In the table below the alphabets are shown side-by-side for comparison, together with a phonetic transcription in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

| № | IPA | UEY | USY | UYY | ULY | № | IPA | UEY | USY | UYY | ULY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /ɑ/ | ئا | А а | A a | 17 | /q/ | ق | Қ қ | Ⱪ ⱪ | Q q | ||

| 2 | /ɛ/ ~ /æ/ | ئە | Ә ә | Ə ə | E e | 18 | /k/ | ك | К к | K k | ||

| 3 | /b/ | ب | Б б | B b | 19 | /ɡ/ | گ | Г г | G g | |||

| 4 | /p/ | پ | П п | P p | 20 | /ŋ/ | ڭ | Ң ң | Ng ng | |||

| 5 | /t/ | ت | Т т | T t | 21 | /l/ | ل | Л л | L l | |||

| 6 | /dʒ/ | ج | Җ җ | J j | 22 | /m/ | م | М м | M m | |||

| 7 | /tʃ/ | چ | Ч ч | Q q | Ch ch | 23 | /n/ | ن | Н н | N n | ||

| 8 | /χ/ | خ | Х х | H h | X x | 24 | /h/ | ھ | Һ һ | Ⱨ ⱨ | H h | |

| 9 | /d/ | د | Д д | D d | 25 | /o/ | ئو | О о | O o | |||

| 10 | /r/ | ر | Р р | R r | 26 | /u/ | ئۇ | У у | U u | |||

| 11 | /z/ | ز | З з | Z z | 27 | /ø/ | ئۆ | Ө ө | Ɵ ɵ | Ö ö | ||

| 12 | /ʒ/ | ژ | Ж ж | Ⱬ ⱬ | Zh zh | 28 | /y/ | ئۈ | Ү ү | Ü ü | ||

| 13 | /s/ | س | С с | S s | 29 | /v/~/w/ | ۋ | В в | V v | W w | ||

| 14 | /ʃ/ | ش | Ш ш | X x | Sh sh | 30 | /e/ | ئې | Е е | E e | Ë ë (formerly É é) | |

| 15 | /ʁ/ | غ | Ғ ғ | Ƣ ƣ | Gh gh | 31 | /ɪ/ ~ /i/ | ئى | И и | I i | ||

| 16 | /f/ | ف | Ф ф | F f | 32 | /j/ | ي | Й й | Y y | |||

Grammar

Uyghur is an agglutinative language with a subject–object–verb word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case, but not gender and definiteness like in many other languages. There are two numbers: singular and plural and six different cases: nominative, accusative, dative, locative, ablative and genitive.[64][65] Verbs are conjugated for tense: present and past; voice: causative and passive; aspect: continuous and mood: e.g. ability. Verbs may be negated as well.[64]

Lexicon

The core lexicon of the Uyghur language is of Turkic stock, but due to different kinds of language contact throughout its history, it has adopted many loanwords. Kazakh, Uzbek and Chagatai are all Turkic languages which have had a strong influence on Uyghur. Many words of Arabic origin have come into the language through Persian and Tajik, which again have come through Uzbek and to a greater extent, Chagatai. Many words of Arabic origin have also entered the language directly through Islamic literature after the introduction of Islam around the 10th century.

Chinese in Xinjiang and Russian elsewhere had the greatest influence on Uyghur. Loanwords from these languages are all quite recent, although older borrowings exist as well, such as borrowings from Dungan, a Mandarin language spoken by the Dungan people of Central Asia. A number of loanwords of German origin have also reached Uyghur through Russian.[66]

Code-switching with Standard Chinese is common in spoken Uyghur, but stigmatized in formal contexts. Xinjiang Television and other mass media, for example, will use the rare Russian loanword aplisin (апельсин, apel'sin) for the word "orange", rather than the ubiquitous Mandarin loanword juze (橘子; júzi). In a sentence, this mixing might look like:[67]

- Mening telfonim guenji (关机; guānjī), shunga sizge duenshin (短信; duǎnxìn) ewetelmidim.

- My (cell) phone shut down, so I wasn’t able to send you a text message.

Below are some examples of common loanwords in the Uyghur language.

| Origin | Source word | Source (in IPA) | Uyghur word | Uyghur (in IPA) | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persian | افسوس | [æfˈsus] | epsus ئەپسۇس | /ɛpsus/ | pity |

| گوشت | [ɡoːʃt] | gösh گۆش | /ɡøʃ/ | meat | |

| Arabic | ساعة | /ˈsaːʕat/ (genitive case) | saet سائەت | /saʔɛt/ | hour |

| Russian | велосипед | [vʲɪləsʲɪˈpʲɛt] | wëlsipit ۋېلسىپىت | /welsipit/ | bicycle |

| доктор | [ˈdoktər] | doxtur دوختۇر | /doχtur/ | doctor (medical) | |

| поезд | [ˈpo.jɪst] | poyiz پويىز | /pojiz/ | train | |

| область | [ˈobləsʲtʲ] | oblast ئوبلاست | /oblast/ | oblast, region | |

| телевизор | [tʲɪlʲɪˈvʲizər] | tëlëwizor تېلېۋىزور | /televizor/ | television set | |

| Chinese | 凉粉, liángfěn | [li̯ɑŋ˧˥fən˨˩] | lempung لەڭپۇڭ | /lɛmpuŋ/ | agar-agar jelly |

| 豆腐, dòufu | [tou̯˥˩fu˩] | dufu دۇفۇ | /dufu/ | bean curd/tofu | |

| 书记, shūjì | [ʂútɕî] | shuji شۇجى | /ʃud͡ʒi/ | secretary[68] | |

| 桌子, zhuōzi | [ʈʂwótsɹ̩] | joza جوزا | /d͡ʒoza/ | table[67] | |

| 冰箱, bīngxiāng | [píŋɕjáŋ] | bingshang بىڭشاڭ | /biŋʃaŋ/ | refrigerator[67] |

See also

References

Notes

- Uyghur at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- "China". Ethnologue.

- "Uyghur – definition of Uyghur by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- "Define Uighur at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Garry F.; Fennig, Charles D. "Uyghur". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Dallas, Texas: Ethnologue. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- "Uyghur". Omniglot. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Engesæth 2009, p. 7

- Hamut, Bahargül. "The Language Choices and Script Debates among the Uyghur in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.7380. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Arik, Kagan (2008). Austin, Peter (ed.). One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0520255609. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Clauson, Gerard (Apr 1965). "Review An Eastern Turki-English Dictionary by Gunnar Jarring". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1/2): 57. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00123640. JSTOR 25202808.

- Coene, Frederik (2009). The Caucasus - An Introduction. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-1135203023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Coene, Frederik (2009). The Caucasus - An Introduction. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series (illustrated, reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 75. ISBN 978-0203870716. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Hahn 1998, pp. 83–84

- Mehmet Fuat Köprülü; Gary Leiser; Robert Dankoff (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-415-36686-1.

- Robert Shaw (1878). A Sketch of the Turki Language: As Spoken in Eastern Turkistan ... pp. 2–.

- Sven Anders Hedin; Erik Wilhelm Dahlgren; Axel Lagrelius; Nils Gustaf Ekholm; Karl Gustaf Olsson; Wilhelm Leche; Helge Mattias Bäckström; Harald Johansson (1905). Scientific Results of a Journey in Central Asia 1899-1902: Lop-Nor, by Sven Hedin [1905. Lithographic institute of the General staff of the Swedish army [K. Boktryckeriet, P.A. Norstedt & söner. pp. 659–.

- Dankoff, Robert (March 1981), "Inner Asian Wisdom Traditions in the Pre-Mongol Period", Journal of the American Oriental Society, American Oriental Society, 101 (1): 87–95, doi:10.2307/602165, JSTOR 602165.

- Brendemoen, Brett (1998), "Turkish Dialects", in Lars Johanson, Éva Csató (ed.), The Turkic languages, Taylor & Francis, pp. 236–41, ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6, retrieved 8 March 2010

- Baldick, Julian (2000), Animal and shaman: ancient religions of Central Asia, I.B. Tauris, p. 50, ISBN 978-1-86064-431-3, retrieved 8 March 2010

- Kayumov, A. (2002), "Literature of the Turkish Peoples", in C. E. Bosworth, M.S.Asimov (ed.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, 4, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 379, ISBN 978-81-208-1596-4, retrieved 8 March 2010

- تۈركى تىللار دىۋانى پۈتۈن تۈركىي خەلقلەر ئۈچۈن ئەنگۈشتەردۇر [The Compendium of Turkic Languages was for all Turkic peoples]. Radio Free Asia (in Uyghur). 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- Badīʻī, Nādira (1997), Farhang-i wāžahā-i fārsī dar zabān-i ūyġūrī-i Čīn, Tehran: Bunyād-i Nīšābūr, p. 57

- Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012. 71 (3): 632. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Rian Thum (13 October 2014). The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History. Harvard University Press. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-674-59855-3.

- Robert Shaw (1878). A Sketch of the Turki Language: As Spoken in Eastern Turkistan ... pp. 102–109.

- C. A. Storey (February 2002). Persian Literature: A Bio-Bibliographical Survey. Psychology Press. pp. 1026–. ISBN 978-0-947593-38-4.

- The Holy Bible in Eastern (Kasiigar) Turki (1950)

- Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2009), "Uyghur", Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Elsevier, p. 1143, ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

- Hahn 1998, p. 379

- Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs (1991). Journal of the Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs, Volumes 12-13. King Abdulaziz University. p. 108. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- J. Todd Reed; Diana Raschke (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-313-36540-9.

- Benjamin S. Levey (2006). Education in Xinjiang, 1884-1928. Indiana University. p. 12.

- Edmund Herzig (30 November 2014). The Age of the Seljuqs. I.B.Tauris. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-78076-947-9.

- David Brophy (4 April 2016). Uyghur Nation. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97046-5.

- Walravens, Hartmut (2006), His Life and Works with Special Emphasis on Japan (PDF), Japonica Humboldtiana, 10, Harrassowitz Verlag, doi:10.18452/6752

- "Did you know Lopnor Uighur is critically endangered?". Endangered Languages. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- Yakup 2005, p. 8

- Hahn 1991, p. 53

- Dwyer 2005, pp. 12–13

- Hann, Chris (2011). "Smith in Beijing, Stalin in Urumchi: Ethnicity, political economy, and violence in Xinjiang, 1759-2009". Focaal—Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology (60): 112.

- Dwyer, Arienne (2005), The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur Identity, Language Policy, and Political Discourse (PDF), Policy Studies, 15, Washington: East-West Center, pp. 12–13, ISBN 1-932728-29-5

- Su, Alice (8 December 2015). "A Muslim Minority Keeps Clashing With the 'China Dream' in the Country's Increasingly Wild West". Vice News. Vice News. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "Uyghur language outlawed in schools of the Uyghur Autonomous Region". Language Log. 2017-08-01.

- Ingram, Ruth (2018-12-28). "The Orwellian Life in Xinjiang Campuses". Bitter Winter. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Byler, Darren (2 January 2019). "The 'Patriotism' Of Not Speaking Uyghur". SupChina. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Sudworth, John (2019-07-04). "China separating Muslim children from families". Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- Shepherd, Christian (12 September 2019). "Fear and oppression in Xinjiang: China's war on Uighur culture". Financial Times. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Gupta, Sonika; Ramachandran, Veena (2016-11-01). "Bilingual Education in Xinjiang in the Post-2009 Period". China Report. 52 (4): 306–323. doi:10.1177/0009445516661885. S2CID 157480863.

- Mamaitiim, Sagittarm (2013-05-28). "The Research on the Language Problems in Xinjiang Uyghur-Han Bilingual Teaching of Mathematics". Xinjiang Normal University.

- "Google Translate supports new languages for the first time in four years, including Uyghur". The Verge. 26 February 2020.

- "Google Translate adds five languages". Google Blog. 26 February 2020.

- Freeman, Joshua L. "Uighur Poets on Repression and Exile". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- Hahn 1998, p. 380

- Hahn 1991, p. 34

- Vaux 2001

- Vaux 2001, pp. 1–2

- Hahn 1991, p. 89

- Hahn 1991, pp. 84–86

- Hahn 1991, pp. 82–83

- Hahn 1991, pp. 80–84

- Hahn 1998, pp. 381–382

- Hahn 1991, pp. 59–84

- Hahn 1991, pp. 22–26

- Engesæth, Yakup & Dwyer 2009, pp. 1–2

- Hahn 1991, pp. 589–590

- Hahn 1998, pp. 394–395

- Thompson, Ashley Claire. Our 'messy' mother tongue: Language attitudes among urban Uyghurs and desires for 'purity' in the public sphere. Diss. University of Kansas, 2013.

- Mi, Chenggang, et al. "Recurrent Neural Network Based Loanwords Identification in Uyghur." Proceedings of the 30th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation: Oral Papers. 2016.

General

- Abdurehim, Esmael (2014), The Lopnor dialect of Uyghur - A descriptive analysis (PDF), Publications of the Institute for Asian and African Studies 17, Helsinki: Unigrafia, ISBN 978-951-51-0384-0

- Duval, Jean Rahman; Janbaz, Waris Abdukerim (2006), An Introduction to Latin-Script Uyghur (PDF), Salt Lake City: University of Utah, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-14 ()

- Dwyer, Arienne (2001), "Uyghur", in Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.), Facts About the World's Languages, H. W. Wilson, pp. 786–790, ISBN 978-0-8242-0970-4

- Engesæth, Tarjei; Yakup, Mahire; Dwyer, Arienne (2009), Greetings from the Teklimakan: A Handbook of Modern Uyghur, Volume 1 (PDF), Lawrence: University of Kansas Scholarworks, ISBN 978-1-936153-03-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-14 ()

- Hahn, Reinhard F. (1991), Spoken Uyghur, London and Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98651-7

- Hahn, Reinhard F. (1998), "Uyghur", in Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes (eds.), The Turkic Languages, Routledge, pp. 379–396, ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6

- Johanson, Lars (1998), "History of Turkic", in Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes (eds.), The Turkic Languages, Routledge, pp. 81–125, ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6

- Vaux, Bert (2001), Disharmony and Derived Transparency in Uyghur Vowel Harmony (PDF), Cambridge: Harvard University, archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2006 ()

- Tömür, Hamüt (2003), Modern Uyghur Grammar (Morphology), trans. Anne Lee, Istanbul: Yıldız, ISBN 975-7981-20-6

- Yakup, Abdurishid (2005), The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur, Turcologica, 63, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-05233-3

Further reading

| Library resources about Uyghur language |

- "The Language Choices and Script Debates among the Uyghur in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China". Bahargül Hamut (Ürümqi, China)and Agnieszka Joniak-Lüthi (Berne). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.7380.

External links

| Look up Uyghur in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Uyghur edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Uyghur language. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Uyghur phrasebook. |

Textbooks

- (free to use) Greetings from the Teklimakan: a handbook of Modern Uyghur from the University of Kansas