Turkish alphabet

The Turkish alphabet (Turkish: Türk alfabesi) is a Latin-script alphabet used for writing the Turkish language, consisting of 29 letters, seven of which (Ç, Ş, Ğ, I, İ, Ö, Ü) have been modified from their Latin originals for the phonetic requirements of the language. This alphabet represents modern Turkish pronunciation with a high degree of accuracy and specificity. Mandated in 1928 as part of Atatürk's Reforms, it is the current official alphabet and the latest in a series of distinct alphabets used in different eras.

History

Early reform proposals and alternate scripts

The earliest known Turkic alphabet is the Orkhon script, also known as the Old Turkish alphabet, the first surviving evidence of which dates from the 7th century. In general, Turkic languages have been written in a number of different alphabets including Uyghur, Cyrillic, Arabic, Greek, Latin, and some other Asiatic writing systems.

Turkish was written using a Turkish form of the Arabic script for over 1,000 years. It was well suited to write Ottoman Turkish which incorporated a great deal of Arabic and Persian vocabulary. However, it was poorly suited to the Turkish part of the vocabulary. Whereas Arabic is rich in consonants but poor in vowels, Turkish is exactly the opposite. The script was thus inadequate at representing Turkish phonemes. Some could be expressed using four different Arabic signs; others could not be expressed at all. The introduction of the telegraph and printing press in the 19th century exposed further weaknesses in the Arabic script.[1]

The Turkic Kipchak Cuman language was written in the Latin alphabet, for example in the Codex Cumanicus.

Some Turkish reformists promoted the adoption of the Latin script well before Atatürk's reforms. In 1862, during an earlier period of reform, the statesman Münuf Pasha advocated a reform of the alphabet. At the start of the 20th century similar proposals were made by several writers associated with the Young Turks movement, including Hüseyin Cahit, Abdullah Cevdet, and Celâl Nuri.[1] The issue was raised again in 1923 during the first Economic Congress of the newly founded Turkish Republic, sparking a public debate that was to continue for several years. A move away from the Arabic script was strongly opposed by conservative and religious elements. It was argued that Romanisation of the script would detach Turkey from the wider Islamic world, substituting a "foreign" (i.e. European) concept of national identity for the traditional sacred community. Others opposed Romanisation on practical grounds; at that time there was no suitable adaptation of the Latin script that could be used for Turkish phonemes. Some suggested that a better alternative might be to modify the Arabic script to introduce extra characters to better represent Turkish vowels.[2] In 1926, however, the Turkic republics of the Soviet Union adopted the Latin script, giving a major boost to reformers in Turkey.[1]

Turkish-speaking Armenians used the Mesrobian script to write Holy Bibles and other books in Turkish for centuries and the linguistic team which invented the modern Turkish alphabet included several Armenian linguists, such as Agop Dilâçar.[3] Karamanli Turkish was, similarly, written with a form of the Greek alphabet.

Introduction of the modern Turkish alphabet

The current 29-letter Turkish alphabet was established as a personal initiative of the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. It was a key step in the cultural part of Atatürk's Reforms,[4] introduced following his consolidation of power. Having established a one-party state ruled by his Republican People's Party, Atatürk was able to sweep aside the previous opposition to implementing radical reform of the alphabet. He announced his plans in July 1928[5] and established a Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) consisting of the following members:[6]

- Ragıp Hulusi Özden

- İbrahim Grantay

- Ahmet Cevat Emre

- Emin Erişirgil

- İhsan Sungu

- Avni Başman

- Falih Rıfkı Atay

- Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın

- Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu

The commission was responsible for adapting the Latin script to meet the phonetic requirements of the Turkish language. The resulting Latin alphabet was designed to reflect the actual sounds of spoken Turkish, rather than simply transcribing the old Ottoman script into a new form.[7]

Atatürk himself was personally involved with the commission and proclaimed an "alphabet mobilisation" to publicise the changes. He toured the country explaining the new system of writing and encouraging the rapid adoption of the new alphabet.[7] The Language Commission proposed a five-year transition period; Atatürk saw this as far too long and reduced it to three months.[8] The change was formalised by the Turkish Republic's law number 1353, the Law on the Adoption and Implementation of the Turkish Alphabet,[9] passed on 1 November 1928. Starting 1 December 1928, newspapers, magazines, subtitles in movies, advertisement and signs had to be written with the letters of the new alphabet. From 1 January 1929, the use of the new alphabet was compulsory in all public communications as well the internal communications of banks and political or social organisations. Books had to be printed with the new alphabet as of 1 January 1929 as well. The civil population was allowed to use the old alphabet in their transactions with the institutions until 1 June 1929.[10]

In the Sanjak of Alexandretta (today's province of Hatay), which was at that time under French control and would later join Turkey, the local Turkish-language newspapers adopted the Latin alphabet only in 1934.[11]

The reforms were also backed up by the Law on Copyrights, issued in 1934, encouraging and strengthening the private publishing sector.[12] In 1939, the First Turkish Publications Congress was organised in Ankara for discussing issues such as copyright, printing, progress on improving the literacy rate and scientific publications, with the attendance of 186 deputies.

Political and cultural aspects

As cited by the reformers, the old Arabic script was much more difficult to learn than the new Latin alphabet.[13] The literacy rate did indeed increase greatly after the alphabet reform, from around 10% to over 90%, but many other factors also contributed to this increase, such as the foundation of the Turkish Language Association in 1932, campaigns by the Ministry of Education, the opening of Public Education Centres throughout the country, and Atatürk's personal participation in literacy campaigns.[14]

Atatürk also commented on one occasion that the symbolic meaning of the reform was for the Turkish nation to "show with its script and mentality that it is on the side of world civilisation".[15] The second president of Turkey, İsmet İnönü further elaborated the reason behind adopting a Latin alphabet:

The alphabet reform cannot be attributed to ease of reading and writing. That was the motive of Enver Pasha. For us, the big impact and the benefit of alphabet reform was that it eased the way to cultural reform. We inevitably lost our connection with Arabic culture.[16]

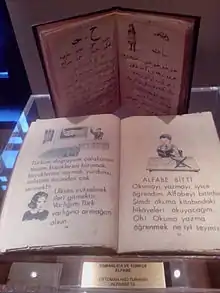

The Turkish writer Şerif Mardin has noted that "Atatürk imposed the mandatory Latin alphabet in order to promote the national awareness of the Turks against a wider Muslim identity. It is also imperative to add that he hoped to relate Turkish nationalism to the modern civilisation of Western Europe, which embraced the Latin alphabet."[17] The explicitly nationalistic and ideological character of the alphabet reform showed in the booklets issued by the government to teach the population the new script. They included sample phrases aimed at discrediting the Ottoman government and instilling updated Turkish values, such as: "Atatürk allied himself with the nation and drove the sultans out of the homeland"; "Taxes are spent for the common properties of the nation. Tax is a debt we need to pay"; "It is the duty of every Turk to defend the homeland against the enemies." The alphabet reform was promoted as redeeming the Turkish people from the neglect of the Ottoman rulers: "Sultans did not think of the public, Ghazi commander [Atatürk] saved the nation from enemies and slavery. And now, he declared a campaign against ignorance [illiteracy]. He armed the nation with the new Turkish alphabet."[18]

The historian Bernard Lewis has described the introduction of the new alphabet as "not so much practical as pedagogical, as social and cultural – and Mustafa Kemal, in forcing his people to accept it, was slamming a door on the past as well as opening a door to the future". It was accompanied by a systematic effort to rid the Turkish language of Arabic and Persian loanwords, often replacing them with revived early Turkic words. However, the same reform also rid the language of many Western loanwords, especially French, in favor of Turkic words, albeit to a lesser degree. Atatürk told his friend Falih Rıfkı Atay, who was on the government's Language Commission, that by carrying out the reform, "we were going to cleanse the Turkish mind from its Arabic roots."[19]

Yaşar Nabi, a leading journalist, argued in the 1960s that the alphabet reform had been vital in creating a new Western-oriented identity for Turkey. He noted that younger Turks, who had only been taught the Latin script, were at ease in understanding Western culture but were quite unable to engage with Middle Eastern culture.[20] The new script was adopted very rapidly and soon gained widespread acceptance. Even so, older people continued to use the Turkish Arabic script in private correspondence, notes and diaries until well into the 1960s.[7]

Letters

The following table presents the Turkish letters, the sounds they correspond to in International Phonetic Alphabet and how these can be approximated more or less by an English speaker.

Uppercase Lowercase Name Name (IPA) Value English approximation A a a /aː/ /a/ As a in father B b be /beː/ /b/ As b in boy C c ce /d͡ʒeː/ /d͡ʒ/ As j in joy Ç ç çe /t͡ʃeː/ /t͡ʃ/ As ch in chair D d de /deː/ /d/ As d in dog E e e /eː/ /e/[lower-alpha 1] As e in red F f fe /feː/ /f/ As f in far G g ge /ɟeː/ /ɡ/, /ɟ/[lower-alpha 2] As g in got Ğ ğ yumuşak ge /jumuˈʃak ɟeː/ /ɰ/ ([ː], [.], [j])[lower-alpha 3] — H h he, ha[lower-alpha 4] /heː/, /haː/ /h/ As h in hot I ı ı /ɯː/ /ɯ/ As e in roses İ i i /iː/ /i/ As ee in feet J j je /ʒeː/ /ʒ/ As s in measure K k ke, ka[lower-alpha 4] /ceː/, /kaː/ /k/, /c/[lower-alpha 2] As k in kit L l le /leː/ /ɫ/, /l/[lower-alpha 2] As l in love M m me /meː/ /m/ As m in man N n ne /neː/ /n/ As n in nice O o o /oː/ /o/ As o in more Ö ö ö /œː/ /œ/ As ur in nurse, with lips rounded P p pe /peː/ /p/ As p in pin R r re /ɾeː/ /ɾ/ As tt in American English better[lower-alpha 5] S s se /seː/ /s/ As s in song Ş ş şe /ʃeː/ /ʃ/ As sh in show T t te /teː/ /t/ As t in tick U u u /uː/ /u/ As oo in zoo Ü ü ü /yː/ /y/ As ee in feet with lips rounded, or close to ue in cue V v ve /veː/ /v/ As v in vat Y y ye /jeː/ /j/ As y in yes Z z ze /zeː/ /z/ As z in zigzag Q[lower-alpha 6] q kû[lower-alpha 6] /cuː/ — — W[lower-alpha 6] w — — — — X[lower-alpha 6] x iks[lower-alpha 6] /ics/ — —

- /e/ is realised as [ɛ]~[æ] before coda /m, n, l, r/. E.g. gelmek [ɟɛlˈmec].

- In native Turkic words, the velar consonants /k, ɡ/ are palatalised to [c, ɟ] when adjacent to the front vowels /e, i, œ, y/. Similarly, the consonant /l/ is realised as a clear or light [l] next to front vowels (including word finally), and as a velarised [ɫ] next to the central and back vowels /a, ɯ, o, u/. These alternations are not indicated orthographically: the same letters ⟨k⟩, ⟨g⟩, and ⟨l⟩ are used for both pronunciations. In foreign borrowings and proper nouns, however, these distinct realisations of /k, ɡ, l/ are contrastive. In particular, [c, ɟ] and clear [l] are sometimes found in conjunction with the vowels [a] and [u]. This pronunciation can be indicated by adding a circumflex accent over the vowel: e.g. gâvur ('infidel'), mahkûm ('condemned'), lâzım ('necessary'), although this diacritic's usage has been increasingly archaic.

- (1) Syllable initially: Silent, indicates a syllable break. That is Erdoğan [ˈɛɾ.do.an] (the English equivalent is approximately a W, i.e. "Erdowan") and değil [ˈde.il] (the English equivalent is approximately a Y, i.e. "deyil"). (2) Syllable finally after /e/: [j]. E.g. eğri [ej.ˈɾi]. (3) In other cases: Lengthening of the preceding vowel. E.g. bağ [ˈbaː]. (4) There is also a rare, dialectal occurrence of [ɰ], in Eastern and lower Ankara dialects.

- The letters h and k are sometimes named ha and ka (as in German), especially in acronyms such as CHP, KKTC and TSK. However, the Turkish Language Association advises against this usage.[21]

- The alveolar tap /ɾ/ doesn't exist as a separate phoneme in English, though a similar sound appears in words like butter in a number of dialects.

- The letters Q, W, and X of the ISO basic Latin alphabet do not occur in native Turkish words and nativised loanwords and are normally not considered letters of the Turkish alphabet (replacements for these letters are K, V and KS). However, these letters are increasingly used in more recent loanwords and derivations thereof such as tweetlemek and proper names like Washington. Two of those letters (Q and X) have commonly accepted Turkish names, while W is usually referred to by its English name double u, its French name double vé, or rarely the Turkish calque of the latter, çift ve.

Of the 29 letters, eight are vowels (A, E, I, İ, O, Ö, U, Ü); the other 21 are consonants.

Dotted and dotless I are distinct letters in Turkish such that ⟨i⟩ becomes ⟨İ⟩ when capitalised, ⟨I⟩ being the capital form of ⟨ı⟩.

Turkish also adds a circumflex over the back vowels ⟨â⟩ and ⟨û⟩ following ⟨k⟩, ⟨g⟩, or ⟨l⟩ when these consonants represent /c/, /ɟ/, and /l/ (instead of /k/, /ɡ/, and /ɫ/):

- â for /aː/ and/or to indicate that the consonant before â is palatalised; e.g. kâr /caɾ/ means "profit", while kar /kaɾ/ means "snow".

- î for /iː/ (no palatalisation implied, however lengthens the pronunciation of the vowel).

- û for /uː/ and/or to indicate palatalisation.

In the case of length distinction, these letters are used for old Arabic and Persian borrowings from the Ottoman Turkish period, most of which have been eliminated from the language. Native Turkish words have no vowel length distinction, and for them the circumflex is used solely to indicate palatalisation.

Turkish orthography is highly regular and a word's pronunciation is usually identified by its spelling.

Distinctive features

Dotted and dotless I are separate letters, each with its own uppercase and lowercase forms. The lowercase form of I is ı, and the lowercase form of İ is i. (In the original law establishing the alphabet, the dotted İ came before the undotted I; now their places are reversed.)[4] The letter J, however, uses a tittle in the same way English does, with a dotted lowercase version, and a dotless uppercase version.

Optional circumflex accents can be used with "â", "î" and "û" to disambiguate words with different meanings but otherwise the same spelling, or to indicate palatalisation of a preceding consonant (for example, while kar /kaɾ/ means "snow", kâr /caɾ/ means "profit"), or long vowels in loanwords, particularly from Arabic. These are seen as variants of "a", "i", and "u" and are becoming quite rare in modern usage.

Software localisation

In software development, the Turkish alphabet is known for requiring special logic, particularly due to the varieties of i and their lowercase and uppercase versions.[22] This has been called the Turkish-I problem.[23]

References

- Zürcher, Erik Jan. Turkey: a modern history, p. 188. I.B.Tauris, 2004. ISBN 978-1-85043-399-6

- Gürçağlar, Şehnaz Tahir. The politics and poetics of translation in Turkey, 1923–1960, pp. 53–54. Rodopi, 2008. ISBN 978-90-420-2329-1

- İrfan Özfatura: "Dilimizi dilim dilim... Agop Dilâçar" (Turkish), Türkiye Gazetesi, April 3, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2012

- Yazım Kılavuzu, Dil Derneği, 2002 (the writing guide of the Turkish language)

- Nationalist Notes, TIME Magazine, July 23, 1928

- "Harf Devrimi". http://dildernegi.org.tr. Dil Derneği. Retrieved 1 November 2019. External link in

|website=(help) - Zürcher, p. 189

- Gürçağlar, p. 55

- "Tūrk Harflerinin Kabul ve Tatbiki Hakkında Kanun" (PDF) (in Turkish).

- Yilmaz (2013). Becoming Turkish (1st ed.). Syracuse, New York. p. 145. ISBN 9780815633174.

- Michel Gilquin (2000). D'Antioche au Hatay (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 70. ISBN 2-7384-9266-5.

- Press and Publications in Turkey, article on Newspot, June 2006, published by the Office of the Prime Minister, Directorate General of Press and Information.

- Toprak, Binnaz. Islam and political development in Turkey, p. 41. BRILL, 1981. ISBN 978-90-04-06471-3

- Harf İnkılâbı Archived 2006-06-21 at the Wayback Machine Text of the speech by Prof. Dr. Zeynep Korkmaz on the website of Turkish Language Association, for the 70th anniversary of the Alphabet Reform, delivered at the Dolmabahçe Palace, on September 26, 1998

- Karpat, Kemal H. "A Language in Search of a Nation: Turkish in the Nation-State", in Studies on Turkish politics and society: selected articles and essays, p. 457. BRILL, 2004. ISBN 978-90-04-13322-8

- İsmet İnönü. "2". Hatıralar (in Turkish). p. 223. ISBN 975-22-0177-6.

- Cited by Güven, İsmail in "Education and Islam in Turkey". Education in Turkey, p. 177. Eds. Nohl, Arnd-Michael; Akkoyunlu-Wigley, Arzu; Wigley, Simon. Waxmann Verlag, 2008. ISBN 978-3-8309-2069-4

- Güven, pp. 180–81

- Toprak, p. 145, fn. 20

- Toprak, p. 145, fn. 21

- "Türkçede "ka" sesi yoktur" (in Turkish). Turkish Language Association on Twitter. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Turkish Java Needs Special Brewing | Java IoT". 2017-07-26. Archived from the original on 2017-07-26. Retrieved 2018-03-17.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Sorting and String Comparison". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2018-03-17.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)