Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism

The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (French: Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchévisme, or LVF) was a unit of the German Army (Wehrmacht) formed by collaborationist volunteers from Vichy France to participate in the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. It was officially designated the 638th Infantry Regiment (Infanterieregiment 638) and was among a number of similar formations recruited in German-occupied Western Europe at the time.

| Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism | |

|---|---|

Sleeve insignia of the LVF, incorporating the French tricolor. | |

| Active | 1941–1944 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Size | 5,800 men (total, 1941–44)[1] |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Edgar Puaud (1943–44) |

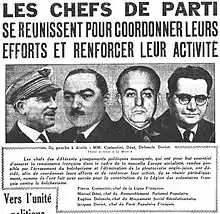

Created in July 1941, the LVF originated as part of a coalition of far-right political factions including Marcel Déat's National Popular Rally, Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party, Eugène Deloncle's Social Revolutionary Movement and Pierre Costantini's French League which were more explicitly supportive of Nazi ideology and collaboration with Nazi Germany. By contrast, the conservative and authoritarian Vichy regime considered itself neutral and were more ambiguous about its dependence on German support. However, the LVF was tolerated by Vichy and received limited personal endorsement from its leading figures.

Smaller than originally anticipated, the LVF was sent to the Eastern Front in October 1941 and suffered heavy losses. It participated in the Battle of Moscow but performed disappointingly in combat. It was deployed for most of its existence in to so-called bandit-fighting operations (Bandenbekämpfung) behind the front line in German-occupied Byelorussia and Ukraine. In total, 5,800 men served in the unit over the course of its existence. After the Allied landings in Normandy and Liberation of France, the LVF was disbanded in September 1944 and its soldiers incorporated into the Waffen SS within the short-lived SS "Charlemagne" Waffen-Grenadier Brigade.

Background

France declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939 at the same time as the United Kingdom. It was invaded and occupied by German forces in May–June 1940 after a disastrous military campaign which pre-war critics of the country's republican regime attributed to the failure of democracy and the corrupting influence of communism, freemasonry and Jews. These were the organising principles of the "National Revolution" declared by the authoritarian Vichy regime under Marshal Philippe Pétain in the aftermath of the defeat. Although a puppet state, the Vichy regime considered itself to be neutral and not part of an alliance with Germany. However, the Vichy regime could not control large parts of France under France under direct German occupation and was challenged by more extreme right-wing French political factions (groupuscules) which often shared a more explicitly Nazi and pro-German ideology than Vichy.[2]

The three main radical factions which emerged as leading proponents of collaborationism were Marcel Déat's National Popular Rally (Rassemblement national populaire), Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (Parti populaire français), and Eugène Deloncle's Social Revolutionary Movement (Mouvement social révolutionnaire).[3] Small in size and widely considered as extremists, these groups looked to German support for their influence but often had poor relations with one another.[4] German overtures towards these collaborationist factions placed great pressure on Vichy to change this stance and encouraged deep suspicion in Pétain's entourage.[4] The German invasion of the Soviet Union which began in June 1941 provided them with an opportunity to consolidate this support by demonstrating their loyalty and political importance to the German occupiers.[5]

Formation

Origins of the LVF

The exact origins of the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (Légion des volontaires français contre le Bolchévisme, LVF) are unclear. However, it is generally believed that Doriot was first to suggest a French unit for the Eastern Front days after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.[5] Rather than looking for Vichy support, he reached out to the German ambassador Otto Abetz.[6] Adolf Hitler approved the unit's creation on 5 July 1941 but mandated that it be organised privately and limited to 10,000 men. This was much smaller than the 30,000 that Doriot and his supporters had imagined but the historian Owen Anthony Davey observes that "the prospect of 30,000 armed French fanatics must have been frightening even to the Germans".[7][8] At around the same time, numerous similar volunteer units were formed in other parts of German-occupied Europe in Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway as well as Francoist Spain.

As part of the LVF's recruitment effort, Doriot, Déat, and Deloncle as well as Pierre Costantini's French League (Ligue française) agreed jointly to establish a Central Committee to manage recruitment and publicity for the unit.[7] They were assisted by even smaller factions in the French extreme-right, such as Jean Boissel's Frankish Front (Front franc), Marcel Bucard's Frankish Movement (Mouvement franciste) and Maurice-Bernard de la Gatinais's French Crusade for National Socialism (Croisade française du national-socialisme).[9] Respected figures from France's intelligentsia and Catholic Church were brought in to the LVF's organising committee to provide more respectability.[10]

Recruitment and training

By July 1941, the LVF was actively recruiting and fundraising across France. Its propaganda emphasised its supposed participation in a Europe-wide "crusade" against communism, drawing from France's medieval history and making little mention of Germany. It established a nation-wide network of 137 recruitment offices, sometimes stationed in expropriated Jewish houses.[11][12] However, recruitment remained poor and struggled to recruit more than 3,000 men in its initial phase.[13] Attempts were made to recruit former soldiers from among the large numbers of prisoners of war in Germany but this was complicated by the German authorities.[14] The Vichy regime provided no direct support to enlistment, although removed existing laws prohibiting French citizens from enlisting in foreign armies. In some contexts, Vichy officials may even have hindered recruitment in the "free zone" it controlled and there were few volunteers from Vichy's own army.[15][8] The number of recruits was disappointing and reflected the additional limitations imposed on the LVF in comparison to other foreign volunteer units in light of France's political importance within German-occupied Europe.[16] As Davey noted:

Such organizations were to serve the diplomatic interests of the Reich, not the interests of a nationalist revival in France. If the Legion had ever become truly popular, German support would in all probability have waned or been withdrawn. The limitation on the size of the Legion was an early indication of the restrictive German attitude towards the growth of collaborationist power. No collaborationist leader would ever receive German support for a nationalist movement in France. The LVF, like all their other enterprises, was destined for failure at the moment of birth.[17]

Despite racialised admission criteria, the unit included several non-white colonials. There were also a number of White Russian émigrés who had lived in France before the war.[18] The first contingent of recruits was assembled at Versailles for a public parade on 27 August 1941 to mark the LVF's creation. At the ceremonies, Pétain's deputy Pierre Laval and Déat were shot and wounded in an attempted assassination by a follower of Deloncle.[17] The following day, German Army doctors rejected almost half of the recruits on medical grounds.[19] Although 10,000 recruits would volunteer for the unit in its first two years of existence, almost half were rejected on these grounds and the unit remained far below the "ceiling" imposed in 1941.[20] Doriot himself enlisted for service in the first contingent, boosting the prestige of the French Popular Party among collaborationist sympathisers in France.[20]

The recruits had been promised that they would fight in French uniforms but, amid continuing Vichy hostility, were folded into the German Army (Wehrmacht). Contrary to promises that it would be an independent French formation, its soldiers were given ordinary Wehrmacht uniform with only a small shield-shaped badge worn on the right arm in the colors of the French flag to signify their origin.[21] It was designated the 638th Infantry Regiment (Infanterieregiment 638) and was sent for basic training in October 1941 at Deba, near Warsaw, in the General Government.

Operational history

By October 1941, there were two battalions of 2,271 men which had 181 officers and an additional staff of 35 German officers. The internal cohesion of the unit was poor and significant internal rivalries existed, losing 400 men to desertion and disease before ever seeing action.[22] There were confrontations between supporters of Doriot and Deloncle.[23] They were sent into combat near Moscow in November and December 1941 as part of the 7th Infantry Division. The LVF lost half their men in action or through frostbite and some individual soldiers deserted to the Red Army in frustration.[24][25] After two weeks, they were withdrawn from the front line and were subsequently used only for role behind the front-line.[23] In 1942 the LVF were assigned to so-called "bandit-fighting" operations (Bandenbekämpfung) against partisans, their supporters, and Jews, in German-occupied Byelorussia (modern-day Belarus). At the same time, the Tricolor Legion (Légion tricolore) was formed in France with Laval's support but was ultimately absorbed into the LVF six months later.[26]

During the spring of 1942, the LVF was reorganized with only the 1st and 3rd battalions. The LVF's French commander, Colonel Roger Labonne, was relieved in mid-1942, and the unit was attached to various German divisions until June 1943 when Colonel Edgar Puaud took command.[27] The two independent battalions were again united in a single regiment and continued fighting partisans, killing partisan supporters and Jews in Ukraine. Historian Timothy Snyder asserts that by the second half of 1942, "German anti-partisan operations were all but indistinguishable from the mass murder of the Jews."[28] In early 1944, the unit again took part in rear-security operations. In June 1944, as Army Group Centre's front collapsed under the Red Army's summer offensive, the LVF was attached to the 4th SS Police Regiment and fought in a delaying action.[29]

Notable members

- Jacques Doriot (1898–1945), former communist turned fascist political activist who founded the French Popular Party in 1936. He was one of the highest profile recruits in 1941 and was awarded the Iron Cross in 1943. He fled to Germany after the Liberation of France to join the Sigmaringen enclave and was killed when his car was attacked by Allied aircraft.

- Saïd Mohammedi (1912–1994), French-Algerian political activist and early proponent of Algerian anti-colonial nationalism. He later fought for the National Liberation Front (Front de libération nationale, FLN) during the Algerian War and was active in post-independence politics in Algeria.[30]

- Armand Pinsard (1887–1953), French fighter pilot and flying ace of World War I who was wounded while serving in the French Air Force in 1940 and had a leg amputated. He served as Inspector-General of the LVF.

Disbandment

The Western Allies staged landings at Normandy in June 1944 and soon began to advance into the rest of France. The LVF was ordered to be dismantled in July 1944 and its soldiers incorporated into the Waffen SS which had begun to integrate French recruits since July 1943. The LVF was officially disbanded on 1 September 1944 by which time most of France had been Liberated. Its remaining personnel were integrated, together with other French volunteers, into the new "Charlemagne" Waffen Grenadier Brigade of the SS (Waffen-Grenadier-Brigade der SS "Charlemagne") on the Eastern Front. After suffering heavy losses in Pomerania, the Brigade was officially reclassified as a division in February 1945 with a remaining strength of just 7,340 men which was significantly reduced in March 1945.[31] Around 100 men remaining in the unit participated in the Battle in Berlin in April–May 1945.[32] Reduced to approximately 30, they finally surrendered to the Red Army near the Potsdamer rail station.

See also

- Normandy-Niemen Regiment — a Gaullist air unit which fought for the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front

References

Citations

- Beyda 2018, p. 304.

- Beyda 2018, p. 289.

- Davey 1971, p. 29.

- Davey 1971, p. 31.

- Davey 1971, p. 32.

- Beyda 2018, p. 297.

- Davey 1971, p. 33.

- Beyda 2018, p. 298.

- Beyda 2018, p. 290, 292.

- Davey 1971, p. 34.

- Davey 1971, p. 36.

- Beyda 2018, p. 302.

- Davey 1971, p. 37.

- Davey 1971, p. 38.

- Beyda 2018, pp. 297-8.

- Beyda 2018, p. 288.

- Davey 1971, p. 40.

- Beyda 2018, pp. 310-1.

- Davey 1971, p. 41.

- Jackson 2001, p. 194.

- Littlejohn 1987, pp. 146, 147.

- Beyda 2018, p. 313.

- Jackson 2001, p. 193.

- Littlejohn 1987, p. 149.

- Beyda 2018, p. 314.

- Littlejohn 1987, pp. 149, 150, 155–157.

- Littlejohn 1987, pp. 149, 157.

- Snyder 2010, p. 240.

- Littlejohn 1987, p. 157.

- "Le premier gouvernement algérien est formé" (in French). Le Monde. 1 October 1962. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Littlejohn 1987, pp. 170, 172.

- Jackson 2001, p. 569.

Bibliography

- Davey, Owen Anthony (1971). "The Origins of the Légion des volontaires français contre le Bolchévisme". Journal of Contemporary History. 6 (4): 29–45.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Littlejohn, David (1987). Foreign Legions of the Third Reich. 1 Norway, Denmark, France. Bender Publishing. ISBN 978-0912138176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beyda, Oleg (2018). "France". In Stahel, David (ed.). Joining Hitler's Crusade: European Nations and the Invasion of the Soviet Union, 1941. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 288–316. ISBN 978-1-316-51034-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198207061.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-46503-147-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Carrard, Philippe (2010). The French Who Fought for Hitler: Memories from the Outcasts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521198226.

- Beyda, Oleg (2016). "'La Grande Armeé in Field Gray': The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism, 1941". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 29 (3): 500–18.

External links

![]() Media related to Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism at Wikimedia Commons