Leuralla

Leuralla is a historic house and museum in Leura, a suburb in the Blue Mountains, in New South Wales, Australia. The property is the site of the Leuralla Toy & Railway Museum.[3] The museum is home to a controversial collection of Nazi-era toys and Nazi memorabilia.[4][5] The museum owner and director is Elizabeth Evatt.[4]

| Leuralla | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | House |

| Architectural style | Federation Free Classical |

| Location | 36 Olympian Parade Leura, New South Wales |

| Coordinates | 33°43′29″S 150°19′47″E |

| Construction started | 1910 |

| Completed | 1914 |

| Governing body | The Evatt Family |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Edward Hewlett Hogben (1875–1936) [1][2] |

| Website | |

| Leuralla Toy & Railway Museum | |

Background

Leuralla was built for the independently wealthy yachtsman and big-game fisherman[6] Harry Andreas[7] (1879 – 1955),[8] his wife Alice and their young family. Harry and Alice Andreas lived at Leuralla until after World War II. In 1928, Clive Evatt QC (1900 – 1984) married Marjorie Andreas, a daughter, of Harry and Alice, and the Evatt family connection to the property began. Clive Evatt Jnr, an Andreas grandson, managed the property. Clive Evatt and his wife, Elizabeth Evatt, are the founders of the present museum. They are responsible for the exhibition of H.V. Evatt QC KStJ (1894 – 1965) memorabilia and for the toy and railway collection displayed in various buildings. Herbert Vere Evatt was Clive Evatt Snr's brother but had no particular connection with Leuralla and had a home of his own in Leura.[9]

As the home of the Katoomba Music Society in the 1930s, Leuralla hosted numerous interesting musical guests including: the internationally renowned pianist Solomon Cutner CBE, known as The Great Solomon; the composer and conductor Sir Eugene Goosens; and music critic and cricket commentator Sir Neville Cardus CBE. During the 1954 Royal Visit the house welcomed Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh.[10] During the 1927 Royal Tour of Australasia, Harry Andreas had acted as a fishing guide for The Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) in the Bay of Islands,[11] whilst the young Princess "Lillibet" was at home in London.

The property

In 1903 a house, known as Leuralla, was built on the current site but was destroyed by bushfire in 1909. Between 1910 and 1914 the present house was built and the design was influenced by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. The house is an example of an early 20th Century permanent residence for a wealthy family. It is an imposing two-storey house set in extensive grounds in the Federation Free Classical style and is notable for its entry portico and stair, symmetry, and bracketed cornice. The walls and chimneys are rendered and the building is on a rockfaced sandstone base. Leuralla has a hipped roof with short projecting hipped wings on the southern and northern sides. The wide external sandstone staircase which has twin flights from the ground under a single storey portico. The portico is topped by a first floor balcony with balustrading. Doric columns complement the entry and the front door is multi-paned and has sidelights. There are symmetrically placed hipped roof bay windows on the northern and southern sides of the portico. The roof is covered in slate and ridged in terracotta. The garage has Federation Anglo-Dutch style influences and its walls are shingled with a weatherboard spandrel. There is a single-storeyed sandstone outbuilding with a gabled roof on the Olympian Parade side of the grounds.[9]

Andreas established an exotic garden from his earliest ownership of Leuralla and much of it was saved from the 1909 bushfire. It was redeveloped around the 1914 house and is still 5 hectares (12 acres) in size. A formal garden lay out was used originally by Andreas and later Paul Sorensen improved the garden overall. There is a sculpture garden on the south side of Olympian Parade. The amphitheatre[12] on the edge of the escarpment takes advantages of its spectacular setting overlooking the Jamieson Valley.[9]

Nazi toy collection

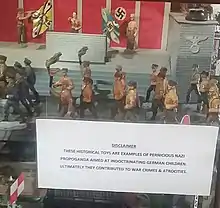

The museum is home to an extensive collection of Nazi-themed toys from wartime Germany that is displayed in several exhibits at the museum. According to Elizabeth Evatt, the museum's owner and director, the Nazi toy collection has been exhibited on display at the museum for over thirty years.[4] The toys are noted for expressing symbols that are associated with the Nazi ideologies and beliefs (those unequivocally rejected today) that were present in Germany at the time the toys were created, sold and used.[13]

In 2014, the issue of the appropriateness of displaying Nazi toys and Nazi memorabilia was raised by local residents, however the museum maintained they would not remove the displays.[4] The issue was subsequently raised by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry (ECAJ), the representative body of the Jewish community in Australia. According to the ECAJ's report on Antisemitism in Australia, while the display of Nazi memorabilia is not illegal, it is often offensive and distressing to Holocaust survivors, their families, and to others who impacted by the savagery of the Nazi regime. An additional concern raised by the ECAJ is that Nazi toys can be used to promote and glorify hatred and violence, including racism, bigotry, and antisemitism.[14]

- Nazi-themes displays at Leuralla

Nazi-themes display at Leuralla

Nazi-themes display at Leuralla Nazi-themes toys at Leuralla with disclaimer

Nazi-themes toys at Leuralla with disclaimer

See also

- National Transport and Toy Museum in Wanaka, New Zealand

- Nuremberg Toy Museum

References

- "DEATH OF MR. E. H. HOGBEN". The Sydney Morning Herald (30, 628). New South Wales, Australia. 3 March 1936. p. 9. Retrieved 26 November 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- HUBERT ARCHITECTS in conjunction with SIOBHAN LAVELLE, R. IAN JACK & COLLEEN MORRIS 28 April 2003, Page 60. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- New South Wales Toy & Railway Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Desiatnik, Shane (4 June 2014). "Museum challenged to remove Nazi era toys". Blue Mountains Gazzette.

- "Leuralla NSW Toy & Railway Museum". Museums & Galleries NSW (NSW Government). Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "DEATH OF MRS. E. P. ANDREAS". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 3 November 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- BD&Ms. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- BD&Ms. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- "NSW Heritage Branch – Leuralla, Garage, Outbuilding, Amphitheatre and Gardens". Office of Environment and Heritage. NSW Government. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Leuralla – Guests Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "ROYAL ANGLERS". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 25 February 1927. p. 9. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Leuralla Cliff-Top Garden and Amphitheatre. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Kooyman, Veronica. "Treasures from Leuralla". Sydney Living Museums. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Executive Council of Australian Jewry (2014). 2014 Report on Antisemitism in Australia.