Lincoln–Douglas debates

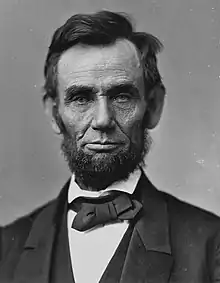

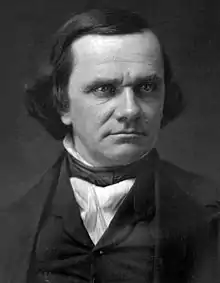

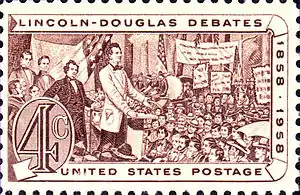

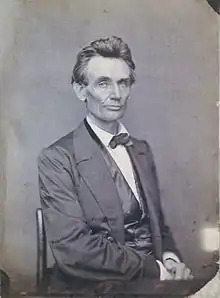

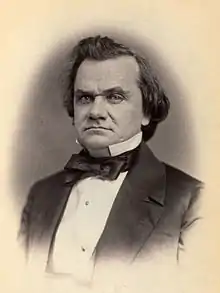

The Lincoln–Douglas debates (also known as The Great Debates of 1858) were a series of seven debates between Abraham Lincoln, the Republican Party candidate for the United States Senate from Illinois, and incumbent Senator Stephen Douglas, the Democratic Party candidate. Until the 17th Constitutional Amendment of 1913, senators were elected by state legislatures, so Lincoln and Douglas were trying to win control of the Illinois General Assembly.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

Political

President of the United States

First term

Second term

Presidential elections

Assassination and legacy

|

||

The debates were the original media event: their goal was to generate publicity. Lincoln and Douglas decided, to maximize it, and for the political symbolism, to hold one debate in each of Illinois’s nine congressional districts. Both candidates had already spoken in Springfield and Chicago within a day of each other, so they decided that their joint appearances would be held in the remaining seven districts. Each debate lasted 3 hours. The format was that one candidate spoke for 60 minutes, then the other candidate spoke for 90 minutes, and then the first candidate was allowed a 30-minute rejoinder. The candidates alternated speaking first. As the incumbent, Douglas spoke first in four of the debates.

The topic was slavery, the great topic of the day, that was tearing the nation apart. It was not slavery in Illinois that was being debated; Illinois, however reluctantly, had been a free state since 1848. It was slavery in the United States, specifically whether slavery would or would not be permitted in the new states to be created out of the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican Cession. These were federal territories without local governing bodies, in fact without any local government except tiny spots or forts. Slavery in the District of Columbia was also a purely federal question, but slavery existed there from the birth of the District, and ending slavery there would free few slaves—they would have been sold in Maryland or Virginia—and it was politically impossible. By focusing on the new western territories the question was clear: what was the federal—national—policy on slavery? The slave state of Missouri, with strong support from the other slave states, wanted the Missouri Compromise to be rescinded and for new slave states to be created, starting with Kansas.

Never had there been newspaper coverage of such intensity. The state’s largest newspapers, from Chicago, sent reporter-stenographers to report complete texts of each debate; thanks to the new railroads, the debates were not hard to reach with Chicago as a starting point. Reporters sent their copy to Chicago using the recently invented telegraph, and the papers immediately published the texts in full, within hours of the speeches having been given. Not only did they appear in Chicago, the newswire of the Associated Press sent messages simultaneously to multiple points, so newspapers all across the country east of the Rocky Mountains printed them, and the debates quickly became national events. Newspapers that supported Douglas edited his speeches to remove any errors made by the stenographers and to correct grammatical errors, while they left Lincoln's speeches in the rough form in which they had been transcribed. In the same way, pro-Lincoln papers edited Lincoln's speeches, but left the Douglas texts as reported. Some of the debate speeches were also published as pamphlets.[1][2]

The debates took place between August and October of 1858. By the last one, in Alton, there were 5,000 to 10,000 present, a crowd never seen before in the United States, according to the Chicago Daily Times.[2]:3 The debates near Illinois's borders (Freeport, Quincy, and Alton) drew large numbers of people from neighboring states.[3][4]

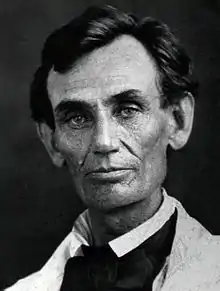

Illinois voters decided Douglas would continue as Senator, so he won the debates. However, the publicity made Lincoln a national figure, and his “A house divided against itself, cannot stand” a prophecy.

As part of his 1860 campaign for president he edited the texts of all the debates and had them published in a book.[5] The book sold well, and helped him get the Republican Party's nomination for president at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago.

Background

Douglas was first elected to the United States Senate in 1846, and he was seeking re-election for a third term in 1858. The issue of slavery was raised several times during his tenure in the Senate, particularly with respect to the Compromise of 1850. As chairman of the committee on U.S. territories, he argued for an approach to slavery called popular sovereignty: electorates in the territories would vote whether to adopt or reject slavery. Decisions previously had been made at a federal level concerning whether slavery was permitted or prohibited in territories. Douglas was successful with passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854.

Lincoln had also been elected to Congress in 1846, and he served a two-year term in the House of Representatives. During his time in the House, he disagreed with Douglas and supported the Wilmot Proviso which sought to ban slavery in any new territory. He returned to politics in the 1850s to oppose the Kansas–Nebraska Act and to help develop the new Republican party.

Before the debates, Lincoln said that Douglas was encouraging fears of amalgamation of the races, with enough success to drive thousands of people away from the Republican Party.[6] Douglas argued that Lincoln was an abolitionist for saying that the American Declaration of Independence applied to blacks as well as whites. Lincoln called a self-evident truth "the electric cord… that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together" of different ethnic backgrounds.[7]

Lincoln argued in his House Divided Speech that Douglas was part of a conspiracy to nationalize slavery. He said that ending the Missouri Compromise ban on slavery in Kansas and Nebraska was the first step in this direction, and that the Dred Scott decision was another step in the direction of spreading slavery into Northern territories. He expressed the fear that the next Dred Scott decision would make Illinois a slave state.[8]

Both Lincoln and Douglas had opposition. Lincoln was a former Whig, and prominent Whig judge Theophilus Lyle Dickey said that he was too closely tied to the abolitionists; he consequently supported Douglas. But Democratic President James Buchanan opposed Douglas for his work to defeat the Lecompton Constitution, which would have made Kansas a slave state, and he set up a rival National Democratic party which drew votes away from him.[9]

The debates

When Lincoln made the debates into a book, in 1860, he included the following material as preliminaries:

- Speech at Springfield by Lincoln, June 16, the "Lincoln's House Divided Speech" speech (in the volume, the erroneous date June 17 is given)

- Speech at Chicago by Douglas, July 9

- Speech at Chicago by Lincoln, July 10

- Speech at Bloomington by Douglas, July 16

- Speech at Springfield by Douglas, July 17 (Lincoln was not present)

- Speech at Springfield by Lincoln, July 17 (Douglas was not present)

- Preliminary correspondence of Lincoln and Douglas, July 24–31[5]

The debates were held in seven towns in the state of Illinois:

- Ottawa on August 21

- Freeport on August 27

- Jonesboro on September 15

- Charleston on September 18

- Galesburg on October 7

- Quincy on October 13

- Alton on October 15

Slavery was the main theme of the Lincoln–Douglas debates, particularly the issue of slavery's expansion into the territories. Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise's ban on slavery in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and replaced it with the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which meant that the people of a territory could vote as to whether to allow slavery. During the debates, both Lincoln and Douglas appealed to the "Fathers" (Founding Fathers) to bolster their cases.[10][11][12]

Ottawa

Lincoln said in the first debate, in Ottawa, that popular sovereignty would nationalize and perpetuate slavery. Douglas replied that both Whigs and Democrats believed in popular sovereignty and that the Compromise of 1850 was an example of this. Lincoln said that the national policy was to limit the spread of slavery, and he mentioned the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 as an example of this policy, which banned slavery from a large part of the Midwest.

The Compromise of 1850 allowed the territories of Utah and New Mexico to decide for or against slavery, but it also allowed the admission of California as a free state, reduced the size of the slave state of Texas by adjusting the boundary, and ended the slave trade (but not slavery itself) in the District of Columbia. In return, the South got a stronger Fugitive Slave Law than the version mentioned in the Constitution.[13] Douglas said that the Compromise of 1850 replaced the Missouri Compromise ban on slavery in the Louisiana Purchase territory north and west of the state of Missouri, while Lincoln said—a topic he went back to in the Jonesboro debate—that Douglas was mistaken in seeing "Popular Sovereignty" and the Dred Scott decision as being in harmony with the Compromise of 1850. To the contrary, "Popular Sovereignty" would nationalize slavery.

There were partisan remarks, such as Douglas' accusations that members of the "Black Republican" party were abolitionists, including Lincoln, and he cited as proof Lincoln's House Divided Speech, in which he said, "I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free."[14] Douglas also charged Lincoln with opposing the Dred Scott decision because "it deprives the negro of the rights and privileges of citizenship." Lincoln responded that "the next Dred Scott decision" could allow slavery to spread into free states. Douglas accused Lincoln of wanting to overthrow state laws that excluded blacks from states such as Illinois, which were popular with the northern Democrats. Lincoln did not argue for complete social equality, but he did say that Douglas ignored the basic humanity of blacks and that slaves did have an equal right to liberty.[15]

Lincoln said that he did not know how emancipation should happen. He believed in colonization in Africa by emancipated slaves, but admitted that it was impractical. He said that it would be wrong for emancipated slaves to be treated as "underlings", but that there was a large opposition to social and political equality and that "a universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, cannot be safely disregarded."[15] He said that Douglas' public indifference would result in the expansion of slavery because it would mold public sentiment to accept it. As Lincoln said, "public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed. Consequently he who molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed."[15] He said that Douglas "cares not whether slavery is voted down or voted up,"[15] and that he would "blow out the moral lights around us" and eradicate the love of liberty.

Freeport

At the debate at Freeport, Lincoln forced Douglas to choose between two options, either of which would damage Douglas' popularity and chances of getting reelected. He asked Douglas to reconcile popular sovereignty with the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision. Douglas responded that the people of a territory could keep slavery out even though the Supreme Court said that the federal government had no authority to exclude slavery, simply by refusing to pass a slave code and other legislation needed to protect slavery.[16] Douglas alienated Southerners with this Freeport Doctrine, which damaged his chances of winning the Presidency in 1860. As a result, Southern politicians used their demand for a slave code to drive a wedge between the Northern and Southern wings of the Democratic Party,[17] splitting the majority political party in 1858.

Douglas failed to gain support in all sections of the country through popular sovereignty. By allowing slavery where the majority wanted it, he lost the support of Republicans led by Lincoln, who thought that Douglas was unprincipled. He lost the support of the South by defeating the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution and advocating a Freeport Doctrine to stop slavery in Kansas, where the majority were anti-slavery.

Jonesboro

In his address in Jonesboro, Lincoln said that slavery expansion endangered the Union and mentioned the controversies caused by it in Missouri in 1820, in the territories conquered from Mexico that led to the Compromise of 1850, and again with the Bleeding Kansas controversy over slavery. He said that the crisis would be reached and passed when slavery was put "in the course of ultimate extinction."

Charleston

Before the debate at Charleston, Democrats held up a banner that read "Negro equality" with a picture of a white man, a negro woman, and a mulatto child.[18]

Lincoln began his address by clarifying that his concerns about slavery did not equate to support for racial equality. He stated:

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races---that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.[19][20]

In his subsequent response, Stephen Douglas said that Lincoln had an ally in Frederick Douglass in preaching "abolition doctrines." He said that Frederick Douglass told "all the friends of negro equality and negro citizenship to rally as one man around Abraham Lincoln." He also charged Lincoln with a lack of consistency when speaking on the issue of racial equality (in the Charleston debate) and cited Lincoln's previous statements that the declaration that all men are created equal applies to blacks as well as whites.[19]

In response to Douglas' questioning of Lincoln's support of negro citizenship, if not full equality, Lincoln further clarified in his rejoinder: "I tell him very frankly that I am not in favor of negro citizenship."[19][20]

Galesburg

At Galesburg, using quotes from Lincoln's Chicago address, Douglas sought again to prove that Lincoln was an abolitionist because of his insistence upon the principle that "all men are equal".

Alton

At Alton, Lincoln tried to reconcile his statements on equality. He said that the authors of the Declaration of Independence "intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects." As Lincoln said, "They meant to set up a standard maxim for the free society which should be familiar to all,—constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere." He contrasted his support for the Declaration with opposing statements made by John C. Calhoun and Senator John Pettit of Indiana, who called the Declaration "a self-evident lie". Lincoln said that Chief Justice Roger Taney and Stephen Douglas were opposing Thomas Jefferson's self-evident truth, dehumanizing blacks and preparing the public mind to think of them as only property. Lincoln thought that slavery had to be treated as a wrong and kept from growing.

As Lincoln said at Alton:

It is the eternal struggle between these two principles -- right and wrong -- throughout the world. ...It is the same spirit that says, "You work and toil and earn bread, and I'll eat it." No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.[21]

These words were set to music by Aaron Copland in his Lincoln Portrait.

Lincoln used a number of colorful phrases in the debates. He said that one argument by Douglas made a horse chestnut into a chestnut horse,[22] and he compared an evasion by Douglas to the sepia cloud from a cuttlefish. Lincoln said, in Quincy, that Douglas' Freeport Doctrine was do-nothing sovereignty that was "as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death."[23]

Results

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The October surprise of the election was former Whig John J. Crittenden's endorsement of Douglas. Non-Republican former Whigs comprised the biggest block of swing voters, and Crittenden's endorsement of Douglas rather than Lincoln reduced Lincoln's chances of winning.[25]

The districts were drawn to favor Douglas' party, and the Democrats won 40 seats in the state House of Representatives while the Republicans won 35. In the State Senate, Republicans held 11 seats and Democrats held 14. Douglas was re-elected by the legislature 54–46, even though Lincoln's Republicans won the popular vote with a percentage of 50.6, by 3,402 votes.[26] However, the widespread media coverage of the debates greatly raised Lincoln's national profile, making him a viable candidate for nomination as the Republican candidate in the upcoming 1860 presidential election.

Ohio Republican committee chairman George Parsons put Lincoln in touch with Ohio's main political publisher, Follett and Foster of Columbus. They published copies of the text in Political Debates Between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas in the Celebrated Campaign of 1858, in Illinois. Four printings were made, and the fourth sold 16,000 copies.[27]

Commemoration

In 1994, C-SPAN aired a series of re-enactments of the debates filmed on location.[28] The debate locations in Illinois feature plaques and statuary of Douglas and Lincoln.[29]

Notes

- Lincoln, Abraham; Douglas, Stephen A. (1858). Speeches of Douglas and Lincoln : delivered at Charleston, Ill., Sept. 18th, 1858.

- Lincoln, Abraham; Douglas, Stephen A. (1858). The campaign in Illinois. Last joint debate. Douglas and Lincoln at Alton, Illinois. [From the Chicago Daily Times. This edition published by partisons of Douglas]. Washington, D.C.

- Nevins, Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852, p. 163

- Abraham Lincoln, Speech at New Haven, Conn., March 6, 1860.

- Lincoln, Abraham; Douglas, Stephen A. (1860). Political Debates between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas, In the Celebrated Campaign of 1858, in Illinois; including the preceding speeches of each, at Chicago, Springfield, etc.; also, the two great speeches of Mr. Lincoln in Ohio, in 1859, as carefully prepared by the reporters of each party, and published at the times of their delivery. Columbus, Ohio: Follett, Foster and Company.

- Abraham Lincoln, Notes for Speech at Chicago, February 28, 1857

- Speech in Reply to Senator Stephen Douglas in the Lincoln-Douglas debates of the 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate, at Chicago, Illinois (July 10, 1858).

- David Herbert Donald, Lincoln, pp. 206–210

- David Herbert Donald, Lincoln, pp. 212–213

- How Lincoln Bested Douglas in Their Famous Debates

- The Founding Fathers and the Election of 1864

- Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to President

- Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: Fruits of Manifest Destiny 1847–1852, pp. 219–345

- First Debate: Ottawa, Illinois, Douglas quote, August 21, 1858

- Debate at Ottawa, Illinois, Lincoln quote, August 21, 1858

- Second Debate: Freeport, Illinois, August 27, 1858

- James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 195

- David Herbert Donald, Lincoln, p. 220

- Lincoln, Abraham (2001). Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 3. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Digital Library Production Services. pp. 145–202. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "Mr. Lincoln and Negro Equality. (Published 1860)". The New York Times. December 28, 1860. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- "Abraham Lincoln on Preserving Liberty". Abraham Lincoln Online. 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- Sparks, Edwin (1918). The Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Dansville, NY: F.A. Owen Publishing Co. p. 30.

- Sparks, Edwin (1918). The Lincoln-Douglas Debates. Dansville, NY: F.A. Owen Publishing Co. p. 125.

- "IL US Senate 1858". OurCampaigns.com. OurCampaigns. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2008). Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America. pp. 273–277, 282.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2008). Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 284–285.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2008). Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 305–306.

- "C-Span, Illinois re-enact Lincoln-Douglas debates History in the Re-making". tribunedigital-baltimoresun. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "The Lincoln-Douglas Debates". www.lookingforlincoln.com. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

Further reading

- On January 1, 2009, BBC Audiobooks America, published the first complete recording of the Lincoln–Douglas Debates, starring actors David Strathairn as Abraham Lincoln and Richard Dreyfuss as Stephen Douglas with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo, Henry R. Luce III Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College. The text of the recording was provided courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Association as presented in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln.

- Jaffa, Harry V. (2009). Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln–Douglas Debates, 50th Anniversary Edition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-39118-2.

- Good, Timothy S. (2007). The Lincoln–Douglas Debates and the Making of a President,. McFarland Press. ISBN 978-0-7864-3065-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lincoln-Douglas debates. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Website of the Stephen A. Douglas Association

- Original Manuscripts and Primary Sources: Lincoln-Douglas Debates, First Edition 1860 Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Illinois Civil War: Debates

- Digital History (archived link)

- Bartleby Etext: Political Debates Between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas

- The Lincoln–Douglas Debates of 1858

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Lincoln–Douglas Debates

- Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Free audio book of "Noted Speeches of Abraham Lincoln," including the Lincoln-Douglas Debates.

- Booknotes interview with Harold Holzer on The Lincoln-Douglas Debates, August 22, 1993.

- Lincoln Douglas Debate Transcripts on the Internet Archive

- Conceptions of race central to Lincoln-Douglas debates – Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois newspaper)