Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American attorney and politician from the state of Maine. In a public service career that spanned over 50 years, he served as the 15th vice president of the United States. The first Republican to hold the office, Hamlin served from 1861 to 1865. He is considered among the most influential politicians to have come from Maine.

Hannibal Hamlin | |

|---|---|

| |

| 15th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 4, 1865 | |

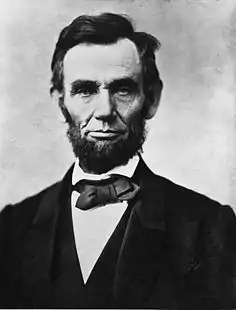

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | John C. Breckinridge |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| United States Minister to Spain | |

| In office December 20, 1881 – October 17, 1882 | |

| President | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | Lucius Fairchild |

| Succeeded by | John W. Foster |

| United States Senator from Maine | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Lot M. Morrill |

| Succeeded by | Eugene Hale |

| In office March 4, 1857 – January 17, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Amos Nourse |

| Succeeded by | Lot M. Morrill |

| In office June 8, 1848 – January 7, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Wyman B. S. Moor |

| Succeeded by | Amos Nourse |

| 26th Governor of Maine | |

| In office January 8, 1857 – February 25, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Wells |

| Succeeded by | Joseph H. Williams |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maine's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1847 | |

| Preceded by | Alfred Marshall |

| Succeeded by | James S. Wiley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 27, 1809 Paris, Massachusetts, U.S. (now Maine, U.S.) |

| Died | July 4, 1891 (aged 81) Bangor, Maine, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Hope Cemetery, Bangor, Maine, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1856) Republican (1856–1891) |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Emery

(m. 1833; died 1855) |

| Children | 6, including Charles, Cyrus, and Hannibal |

| Signature | |

A native of Paris, Maine (part of Massachusetts until 1820), Hamlin managed his father's farm before becoming a newspaper editor. He studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1833, and began to practice in Hampden, Maine. Originally a Democrat, Hamlin began his political career with election to the Maine House of Representatives in 1835 and an appointment to the military staff of the Governor of Maine. As an officer in the militia, he took part in the 1839 negotiations that helped end the Aroostook War. In the 1840s Hamlin was elected to and served in the United States House of Representatives. In 1848 the state house elected him to the United States Senate, where he served until January 1857. He served temporarily as governor for six weeks in the beginning of 1857, after which he returned to the Senate. Hamlin was an active opponent of slavery; he supported the Wilmot Proviso and opposed the Compromise of 1850. In 1854, he strongly opposed passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Hamlin's increasingly anti-slavery views caused him to leave the Democratic Party for the newly formed Republican Party in 1856.

In the 1860 election, Hamlin was the Republican nominee for Vice President. Selected to run with Abraham Lincoln, who was from Illinois, Hamlin was chosen in part to bring geographic balance to the ticket and in part because as a former Democrat, he could work to convince other anti-slavery Democrats that their future lay with the Republican Party. The Lincoln and Hamlin ticket was successful, and Hamlin served as Vice President from 1861 to 1865, which included all but the last month of the American Civil War. The first Republican Vice President, Hamlin held the office in an era when the office was considered more a part of the legislative branch than the executive; he was not personally close to Lincoln and did not play a major role in his administration. Even so, Hamlin supported the administration's legislative program in his role as presiding officer of the Senate, and he looked for other ways to demonstrate his support for the Union, including a term of service in a Maine militia unit during the war.

For the 1864 election, Hamlin was replaced as Vice Presidential nominee by Andrew Johnson, a Southern Democrat chosen for his appeal to Southern Unionists. After leaving the vice presidency, Hamlin served as Collector of the Port of Boston, a lucrative post to which he was appointed by Johnson after the latter succeeded to the presidency following Lincoln's assassination. However, Hamlin later resigned as Collector because of his disagreement with Johnson over Reconstruction of the former Confederacy.

In 1869, Hamlin was elected again to the U.S. Senate, and he served two terms. After leaving the Senate in 1881, he served briefly as United States Ambassador to Spain before returning to Maine in late 1882. In retirement, Hamlin was a resident of Bangor, Maine, where he died in 1891. He was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Bangor.

Early life

Hamlin was born to Cyrus Hamlin and his wife Anna, née Livermore, in Paris (now in Maine, then a part of Massachusetts). He was a descendant in the sixth generation of English colonist James Hamlin, who had settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1639. He was a grandnephew of U.S. Senator Samuel Livermore II[1] of New Hampshire.

According to folklore, Hamlin's life was saved when he was an infant by a Native American medicine woman named Molly Ockett. Hamlin was gravely ill and Molly Ockett prescribed that he be given warm cow's milk after which he recovered.

Hamlin attended the district schools and Hebron Academy and later managed his father's farm. From 1827 to 1830 he published the Oxford Jeffersonian newspaper in partnership with Horatio King.[2]

He studied law with the firm headed by Samuel Fessenden,[3] was admitted to the bar in 1833, and began practicing in Hampden, Maine, where he lived until 1848.[4]

Personal life

Hamlin married Sarah Jane Emery of Paris Hill in 1833. Her father was Stephen Emery, who was appointed as Maine's Attorney General in 1839–1840.[5] Hamlin and Sarah had four children together: George, Charles, Cyrus and Sarah.[6]

His wife died in 1855. The next year, Hamlin married Sarah's half-sister, Ellen Vesta Emery in 1856. They had two children together: Hannibal E. and Frank. Ellen Hamlin died in 1925.[7]

Political beginnings

Hamlin's political career began in 1835, when he was elected to the Maine House of Representatives. Appointed a Major on the staff of Governor John Fairfield, he served with the militia in the bloodless Aroostook War of 1839. He facilitated negotiations between Fairfield and Lieutenant Governor John Harvey of New Brunswick, which helped reduce tensions and make possible the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, which ended the war.[8]

Hamlin unsuccessfully ran for the United States House of Representatives in 1840 and left the State House in 1841. He later was elected to two terms in the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1843 to 1847. He was elected by the state legislature to fill a U.S. Senate vacancy in 1848, and to a full term in 1851. A Democrat at the beginning of his career, Hamlin supported the candidacy of Franklin Pierce in 1852.

From the very beginning of his service in Congress, Hamlin was prominent as an opponent of the extension of slavery. He was a conspicuous supporter of the Wilmot Proviso and spoke against the Compromise of 1850. In 1854, Hamlin strongly opposed the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise. After the Democratic Party endorsed that repeal at the 1856 Democratic National Convention, on June 12, 1856, he withdrew from the Democratic Party and joined the newly organized Republican Party, causing a national sensation.

The Republicans nominated Hamlin for Governor of Maine in the same year. He carried the election by a large majority and was inaugurated on January 8, 1857. In the latter part of February 1857, however, he resigned the governorship. He returned to the United States Senate, serving from 1857 to January 1861.

Vice presidency

Hamlin was nominated by the Republican Party to serve as Vice President of the United States in the 1860 presidential election on a ticket with former Representative Abraham Lincoln.[9] Given that Lincoln was from Illinois, a vice presidential nominee from Maine made sense in terms of regional balance. As a former Democrat, Hamlin could persuade other anti-slavery Democrats that joining the Republican Party was the only way to ensure slavery's demise.

Hamlin and Lincoln were not close personally but had a good working relationship. At the time, the Vice President was part of the legislative branch in his role as President of the Senate and did not attend cabinet meetings; Hamlin did not regularly visit the White House. Mary Todd Lincoln and Hamlin disliked each other. For his part, Hamlin complained, "I am only a fifth wheel of a coach and can do little for my friends."[10]

He had little influence in the Lincoln Administration, although he urged both the Emancipation Proclamation[11] and the arming of Black Americans.[12] He strongly supported Joseph Hooker's appointment as commander of the Army of the Potomac,[13] which ended in failure at the Battle of Chancellorsville.[14]

Beginning in 1860, Hamlin was a member of Company A of the Maine State Guard, a militia unit.[15] When the company was called up in the summer of 1864, Hamlin was told that because of his position as Vice President, he did not have to take part in the muster. He opted to serve, arguing that he could set an example by doing the duty expected of any citizen, and the only concession made because of his office was that he was quartered with the officers. He reported to Fort McClary in July, initially taking part in routine assignments including guard duty, and later taking over as the company cook. He was promoted to corporal during his service, and mustered out with the rest of his unit in mid-September.[16][17][18]

In June 1864, the Republicans and War Democrats joined to form the National Union Party. Although Lincoln was renominated, War Democrat Andrew Johnson of Tennessee was named to replace Hamlin as Lincoln's running mate. Lincoln was seeking to broaden his base of support and was also looking ahead to Southern Reconstruction, at which Johnson had proven himself adept as military governor of occupied Tennessee. Hamlin, by contrast, was an ally of the Northern "Radical Republicans" (who would later impeach Johnson). Lincoln and Johnson were elected in November 1864, and Hamlin's term expired on March 4, 1865.

After leaving the vice presidency Hamlin served briefly as Collector of the Port of Boston. Appointed to the post by Johnson, Hamlin resigned in protest over Johnson's Reconstruction policy and accompanying efforts to build a political following loyal to him after he had been repudiated by the Republicans. Republicans had supported Johnson as part of the National Union ticket during the war, but opposed him after he became President and his position on Reconstruction deviated from theirs.[19]

Although Hamlin narrowly missed becoming President, his vice presidency would usher in a half-century of sustained national influence for the Maine Republican Party. In the period 1861–1911, Maine Republicans occupied the offices of Vice President, Secretary of the Treasury (twice), Secretary of State, President pro tempore of the United States Senate, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives (twice), and would field a presidential nominee in James G. Blaine, a level of influence in national politics unmatched by subsequent Maine political delegations.

Later life

Not content with private life, Hamlin returned to the U.S. Senate in 1869 to serve two more 6-year terms before declining to run for re-election in 1880 because of an ailing heart. His last duty as a public servant came in 1881 when Secretary of State James G. Blaine convinced President James A. Garfield to name Hamlin as United States Ambassador to Spain. Hamlin received the appointment on June 30, 1881, and held the post until October 17, 1882.

Upon returning from Spain, Hamlin retired from public life to his home in Bangor, Maine, which he had purchased in 1851. The Hannibal Hamlin House – as it is known today – is located in central Bangor at 15 5th Street; incorporating Victorian, Italianate, and Mansard-style architecture, the mansion was posted to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.[20]

Hamlin was elected as a Third Class Companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. Third Class was the MOLLUS division created to recognize civilians who had contributed outstanding service to the Union during the war.

Death

On Independence Day, July 4, 1891, Hamlin collapsed and fell unconscious while playing cards at the Tarratine Club he founded in downtown Bangor. He was then placed on one of the club's couches. He died a few hours later of natural causes. He was 81. The couch is preserved at the Bangor Public Library.[21] Hannibal Hamlin was buried in the Hamlin family plot at Mount Hope Cemetery in Bangor, Maine. Hamlin outlived six of his successors in the vice presidency: Andrew Johnson, Schuyler Colfax, Henry Wilson, William A. Wheeler, Chester A. Arthur, and Thomas A. Hendricks.

Family

Hamlin had four sons who grew to adulthood: Charles Hamlin, Cyrus Hamlin, Hannibal Emery and Frank Hamlin. Charles and Cyrus served in the Union forces during the Civil War, both becoming generals, Charles by brevet. Cyrus was among the first Union officers to argue for the enlistment of black troops, and himself commanded a brigade of freedmen in the Mississippi River campaign. Charles and sister Sarah were present at Ford's Theater the night of Lincoln's assassination. Hannibal Emery Hamlin was Maine Attorney General from 1905 to 1908. Hannibal Hamlin's great-granddaughter Sally Hamlin was a child actor who made many spoken word recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company in the early years of the 20th century.

Hannibal's older brother, Elijah Livermore Hamlin, was president of the Mutual Fire Insurance Co. of Bangor, and the Bangor Institution for Savings.[22] He was twice an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Maine in the late 1840s, though he did serve as Mayor of Bangor in 1851–52. The brothers were members of different political parties (Hannibal a Democrat, and Elijah a Whig) before both becoming Republican in the later 1850s.[23]

Hannibal's nephew (Elijah's son) Augustus Choate Hamlin was a physician, artist, mineralogist, author, and historian. He was also Mayor of Bangor in 1877–78, and a founding member of the Bangor Historical Society.[24]

Augustus served as surgeon in the 2nd Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War, eventually becoming a U.S. Army Medical Inspector, and later the Surgeon General of Maine. He wrote books about Andersonville Prison and the Battle of Chancellorsville.[25] Hannibal's grand-nephew (Elijah's grandson) Isaiah K. Stetson was Speaker of the Maine House of Representatives in 1899–1900,[26] and owned a large company in Bangor which manufactured and shipped lumber and ice and ran a shipyard and marine railway.[27]

Hannibal's first cousin Cyrus Hamlin, who was a graduate of the Bangor Theological Seminary, became a missionary in Turkey, where he founded Robert College. He later became president of Middlebury College in Vermont. His son, A. D. F. Hamlin, Hannibal's first cousin once removed, became a professor of architecture at Columbia University and a noted architectural historian. There are biographies of Hamlin by his grandson Charles E. Hamlin (published 1899, reprinted 1971) and by H. Draper Hunt (published 1969)[28]

Honors

Hamlin County, South Dakota is named in his honor, as are Hamlin, Kansas; Hamlin, New York; Hamlin, West Virginia; Hamlin Township; Hamlin Lake in Mason County, Michigan; and, Hamlin, a small Maine village that is a U.S.–Canada border crossing with Grand Falls, New Brunswick. There are statues in Hamlin's likeness in the United States Capitol and in a public park (Norumbega Mall) in Bangor, Maine.

There is also a building on the University of Maine Campus, in Orono, named Hannibal Hamlin Hall. This burned down in 1945, in a fire that killed two students, but was subsequently rebuilt. Hannibal Hamlin Memorial Library is next to his birthplace in Paris, Maine.

The Hampden Maine Historical Society exhibit a restoration of his first law office at their Kinsley House Museum grounds.

Hamlin's house in Bangor subsequently housed the Presidents of the adjacent Bangor Theological Seminary. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as is Hamlin's birthplace in Paris, Maine (as part of the Paris Hill Historic District).

Hamlin Park in Chicago is named in his honor.[29]

In popular culture

Hamlin appears briefly in three alternate history writings by Harry Turtledove: The Guns of the South, Must and Shall, and How Few Remain.[30][31][32]

Fallout 3 features a character named Hannibal Hamlin. He is shown to be an admirer of Abraham Lincoln and was a former slave who now leads an anti-slavery militia of sorts composed of other former slaves.

See also

References

- Hamlin, Charles Eugene (1899). The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin by his Grandson Charles Eugene Hamlin. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Riverside Press. p. 2,12. ISBN 9780722291283.

- Waterman, Charles E. (August 1, 1891). "The Birthplace of Hannibal Hamlin". The New England Magazine. Boston, MA. 4 (6): 731.

- Hamlin, Charles Eugene (1899). The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Riverside Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780722291283.

- "HAMLIN, Hannibal - Biographical Information". US Congress. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Barrett, Joseph Hartwell (1860). Life of Abraham Lincoln (of Illinois). Moore, Wilstach, Keys & Co.: Cincinnati, OH. p. 196.

- "Hamlin Family Papers, 1802-1975". University of Maine Digital Commons. 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- "Fogler Library: Finding Guide to the Hamlin Family Papers". Library.umaine.edu. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- "Who Was Vice President During Lincoln's Administration?". WorldAtlas. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Abraham Lincoln: Campaigns and Elections (Winning Republican Support)". The Miller Center. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Abraham Lincoln's White House – Hannibal Hamlin (1809–1891)". Mrlincolnswhitehouse.org. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-7432-1846-7.

- Dray, Philip (2008). Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-618-56370-8.

- Taaffe, Stephen R. (2006). Commanding the Army of the Potomac. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7006-1451-6.

- Steers, Edward Jr. (2007). Lincoln Legends: Myths, Hoaxes, and Confabulations Associated with Our Greatest President. Lexington, KY: University Press of KY. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8131-2466-7.

- "Fort McClary Garrisoned; VICE-PRESIDENT HAMLIN AMONG THE PRIVATES. (Published 1864)". July 8, 1864 – via NYTimes.com.

- Laird, Archibald (1980). The Near Great—Chronicle of the Vice Presidents. Boston, MA: Christopher Publishing House. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8158-0381-2.

- Scroggins, Mark (1994). Hannibal: The Life of Abraham Lincoln's First Vice President. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. pp. 210–11. ISBN 978-0-8191-9440-4.

- "Civil War Index - 1st Maine State Guards". civilwarindex.com.

- Hamlin, Charles Eugene (1899). The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Riverside Press. pp. 505–509. ISBN 9780722291283.

- "The Hannibal Hamlin House posted to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979". Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- "Hannibal Hamlin Death Couch". Atlas Obscura.

- Augustus C. Smith, Bangor, Brewer, and Penobscot Co. Directory, 1859–60 (Bangor, 1859)

- "The late Hon. Elijah L. Hamlin" (PDF). The New York Times. July 23, 1872. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- Moorhead, Warren King (1980). A Report on the Archeology of Maine. New York City: AMS Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0404156435.

- Augustus Choate Hamlin (1896). The Battle of Chancellorsville. Bangor, Maine.

- "Speakers of the Maine House of Representatives 1820–". Maine State Legislature. October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- "Isaiah K. Stetson profile". Representative Men of Maine. 1893. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- Worldcat. The life and times of Hannibal Hamlin. OCLC 1559174.

- District, Chicago Park. "Hamlin Park | Chicago Park District". www.chicagoparkdistrict.com. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- Turtledove, Harry (1992). The Guns of the South. New York: Random House. pp. 248. ISBN 0345384687 – via Google Books.

...'but when it finally convened, it renominated Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin...'

- "Russo-Japanese War – The Dogger Bank Incident Goes Wrong". www.changingthetimes.net. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- Turtledove, Harry (1998). How Few Remain. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 9781444744965.

Bibliography

- Glonek, James Francis (1948). Hannibal Hamlin and the Vice-Presidency. University of Wisconsin--Madison.

- "Hannibal Hamlin, 15th Vice President (1861-1865)". United States Senate. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- Harry Draper Hunt (1969). Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, Lincoln's First Vice-President. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2142-3. OCLC 24587.

- Charles Eugene Hamlin (1899). The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780722291283. OCLC 1559174.

- Speiser, Matt (2006). "The Ticket's Other Half: How and Why Andrew Johnson Received the 1864 Vice Presidential Nomination". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 65 (1): 42–69. JSTOR 42628582.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hannibal Hamlin. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Hannibal Hamlin. |

- United States Congress. "Hannibal Hamlin (id: H000121)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Biography at Mr. Lincoln's White House

- The life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin by Charles Eugene Hamlin

- Bangor in Focus: Hannibal Hamlin

- Ted Widmer (November 22, 2010). "Lincoln Speaks". Opinionator (department). The New York Times.

- Hamlin Memorial Library and Museum

| U.S. House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alfred Marshall |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maine's 6th congressional district 1843–1847 |

Succeeded by James S. Wiley |

| U.S. Senate | ||

| Preceded by Wyman B. S. Moor |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Maine 1848–1857 Served alongside: James W. Bradbury, William P. Fessenden |

Succeeded by Amos Nourse |

| Preceded by Amos Nourse |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Maine 1857–1861 Served alongside: William P. Fessenden |

Succeeded by Lot M. Morrill |

| Preceded by Lot M. Morrill |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Maine 1869–1881 Served alongside: William P. Fessenden, Lot M. Morrill, James G. Blaine |

Succeeded by Eugene Hale |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Anson Morrill |

Republican nominee for Governor of Maine 1856 |

Succeeded by Lot M. Morrill |

| Preceded by William L. Dayton |

Republican nominee for Vice President of the United States 1860 |

Succeeded by Andrew Johnson1 |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Samuel Wells |

Governor of Maine 1857 |

Succeeded by Joseph H. Williams |

| Preceded by John C. Breckinridge |

Vice President of the United States 1861–1865 |

Succeeded by Andrew Johnson |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Lucius Fairchild |

United States Minister to Spain 1881–1882 |

Succeeded by John W. Foster |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. Lincoln and Johnson ran on the National Union ticket in 1864. | ||

\