Elijah Parish Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (November 9, 1802 – November 7, 1837) was an American Presbyterian minister, journalist, newspaper editor, and abolitionist. He was shot and killed by a pro-slavery mob in Alton, Illinois, during their attack on the warehouse of Benjamin Godfrey and W. S. Gillman, where Lovejoy's press and abolitionist materials were stored.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 9, 1802 |

| Died | November 7, 1837 (aged 34) |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Resting place | Alton Cemetery |

| Education | Waterville College |

| Spouse(s) | Celia Ann French (m. 1835) |

| Signature | |

According to John Quincy Adams, the murder "[gave] a shock as of an earthquake throughout this country".[1]:97–98 "The Boston Recorder declared that these events called forth from every part of the land 'a burst of indignation which has not had its parallel in this country since the Battle of Lexington.'"[1]:98 When informed at a meeting about the murder, John Brown said publicly: "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery."[1]:101

Early life and education

Lovejoy was born at his grandfather's frontier farmhouse near Albion, Maine, as the first of the nine children of Elizabeth (Pattee) Lovejoy and Daniel Lovejoy.[2] Lovejoy's father was a Congregational preacher and farmer, and his mother was a homemaker and a devout Christian. Daniel Lovejoy named his son "Elijah Parish" in honor of his close friend and mentor, Elijah Parish, a minister who was also involved in politics.[3] Due to his own lack of an education, he encouraged his sons—Elijah, Daniel, Joseph Cammett, Owen, and John—to become educated men. As a result, Elijah was taught to read the Bible and other religious texts at an early age.[4]

After completing his early studies in public schools, Lovejoy attended the Academy at Monmouth and China Academy. After becoming proficient enough in Latin and mathematics, he enrolled at Waterville College (now Colby College) in Waterville, Maine, as a sophomore in 1823.[4] He excelled in his studies, and upon faculty recommendation, from 1824 until his 1826 graduation, while still an undergraduate, he also served as headmaster of Colby's associated high school, the Latin School (later Coburn Classical Institute). Lovejoy received financial support from minister Benjamin Tappan to continue his attendance at Waterville College.[5] His cousin Nathan A. Farwell later served as a U.S. Senator from Maine.

In September 1826, Lovejoy graduated cum laude from Waterville College,[6] of which he was valedictorian.[7] During the winter and spring, he taught at China Academy. Dissatisfied with daily teaching, Lovejoy thought about moving to the Southern or Western United States. His former teachers at Waterville College advised him that he would best serve God in the West.[8] Agreeing, Lovejoy in May 1827 moved to Boston to earn money for his journey, having settled on Illinois as his destination.[9] Unsuccessful at finding work, he started to Illinois by foot. He stopped in New York City in mid-June, to try to find work. He eventually landed a position with the Saturday Evening Gazette as a newspaper subscription peddler. For nearly five weeks, he walked up and down streets, knocking on peoples' doors and wheedling passersby, in hopes of getting them to subscribe to the newspaper.[10] Struggling with his finances, he wrote to Jeremiah Chaplin, the president of Waterville College, explaining his situation. Chaplin sent the money that his former student so needed.[10] Lovejoy promptly embarked on his journey to Illinois, reaching Hillsboro, Montgomery County, in the fall of 1827. Lovejoy did not think he could do well in Illinois's scantly settled land, so he headed for St. Louis, where he settled the same year.[11]

St. Louis

A major port in a slave state surrounded by free ones, St. Louis was a center of both abolitionist and pro-slavery factions. From 1814 to 1860, more than three hundred freedom suits were filed by slaves to gain freedom, often based on their having lived in free territory with their masters. At the same time, it was an area where both free Blacks and slaves worked in the city, especially on the waterfront and steamboats.

In St. Louis, Lovejoy quickly became ill, but once recovered, he operated a school with a friend, modeled on high schools in the East. His interest in teaching waned, however, when local editors began accepting his poems in their newspapers. This led him to a partnership with T. J. Miller as an editor on the St. Louis Times, a paper that supported Henry Clay for President in 1832. Working at the Times introduced him to like-minded community leaders, many of whom were members of the American Colonization Society, that supported sending freed American blacks to Africa. Among these new acquaintances were Edward Bates, Hamilton R. Gamble, and Archibald Gamble. Lovejoy occasionally hired slaves to work with him at the paper, one of whom, William Wells Brown, later recounted his experience in a memoir. Brown described Lovejoy as "a very good man, and decidedly the best master that I had ever had. I am chiefly indebted to him, and to my employment in the printing office, for what little learning I obtained while in slavery."[12]

He worked as an editor of an anti-Jacksonian newspaper, the St. Louis Observer, and ran a school. Five years later, he studied at the Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey and became an ordained Presbyterian preacher. Returning to St. Louis, he set up a church and resumed work as editor of the Observer. His editorials criticized slavery and other church denominations.

Lovejoy struggled with his interest in religion, often writing his parents about his sinfulness and rebellion against God. He attended revival meetings in 1831 led by William S. Potts, pastor of First Presbyterian Church that rekindled his interest in religion for a time. However, Lovejoy admitted to his parents that "gradually these feelings all left me, and I returned to the world a more hardened sinner than ever."[13] A year later, Lovejoy found the call to God he desired. In 1832, influenced by the Christian revivalist movement led by abolitionist David Nelson, he joined the First Presbyterian Church and decided to become a preacher.[14] He sold his interest in the Times, returned East to study at the Princeton Theological Seminary, and upon completion, went to Philadelphia, where he became an ordained minister of the Presbyterian Church in April 1833. Friends in St. Louis offered to finance a Presbyterian newspaper there if Lovejoy would agree to edit it. Lovejoy accepted and on November 22, 1833, the first issue of the St. Louis Observer was published.[13]

In spring 1834, Lovejoy penned a number of articles and editorials criticizing the Catholic Church. The large Catholic community of St. Louis was offended by these attacks, but Lovejoy did not back down. He continued his critical writings to include editorials on tobacco and liquor as well. That same year, Lovejoy began editorializing on slavery, the most controversial social issue of that time. His views were influenced by Nelson, an abolitionist. In 1835, the Missouri Republican began suggesting gradual emancipation in Missouri, and Lovejoy supported this endeavor through the Observer. Lovejoy's views on slavery began to incite complaints and threats. By October 1835, there were rumors of mob action against the Observer. A group of prominent St. Louisans, including many of Lovejoy's friends, wrote a letter pleading with him to cease discussion of slavery in the newspaper. Lovejoy was away from the city at this time and the publishers declared that no further articles on slavery would appear during Lovejoy's absence and, when he returned, he would follow a more rigorous editorial policy. Lovejoy wrote a response to the letter, making it clear he did not agree with the publishers' policy. As tensions over slavery escalated in St. Louis, Lovejoy would not back down from his convictions and he had a sense that he would become a martyr for the cause. He was asked to resign as editor of the Observer, to which he agreed. However, the newspaper's owners released the Observer property to the moneylender who held the mortgage and the new owners asked Lovejoy to stay on as editor.[13]

Lovejoy and The Observer continued to be embroiled in controversy. In April 1836, a mulatto boatman, Francis McIntosh, was arrested by two policemen and, en route to the jail, McIntosh grabbed a knife and stabbed both men. One was killed and the other seriously injured. Although McIntosh attempted to escape, he was caught and a mob tied him up and burned him to death. Some of the mob were brought before a grand jury to face charges. However, the presiding judge, Judge Lawless, refused to convict anyone and considered the crime a spontaneous mob action without any specific people to prosecute. The judge made remarks insinuating that abolitionists, including Lovejoy and the Observer, had incited McIntosh into stabbing the policemen. With already negative attention on him, Lawless' opinion did nothing to help Lovejoy and in May, Lovejoy decided to move the Observer to Alton, Illinois.[13]

Marriage and family

In 1835, Lovejoy married Celia Ann French, of St. Charles, Missouri, and they had two children.

Move to Alton

In May 1836, after pro-slavery forces in St. Louis destroyed his printing press for the third time, Lovejoy left the city and moved across the river to Alton, in the free state of Illinois. Before he could move the press, an angry mob broke into the Observer office and vandalized it. Only Alderman and future mayor Bryan Mullanphy attempted to stop the crime, and no policemen or city officials intervened. Lovejoy packed what remained of the office for shipment to Alton. The printing press sat on the riverbank, unguarded, overnight and was destroyed and thrown into the Mississippi River.[13]

Although Illinois was a free state, Alton, Illinois was a center for slave catchers and pro-slavery forces. Many escaped slaves crossed the Mississippi River from Missouri, a slave state. Alton had been settled by pro-slavery Southerners who thought Alton should not become a haven for escaped slaves.[15]

In 1837 he started the Alton Observer, also an abolitionist paper. He served as pastor at Upper Alton Presbyterian Church (now College Avenue Presbyterian Church).[16]

Lovejoy's views on slavery became more extreme and he called for a convention to discuss the formation of a state Anti-Slavery Society. Many in Alton began questioning allowing Lovejoy to continue printing in their town. After an economic crisis in March 1837, Alton citizens wondered if Lovejoy's views were contributing to hard times. They felt Southern states, or even St. Louis, might not want to do business with their town if they continued to harbor an abolitionist.[13]

Lovejoy held the Illinois Antislavery Congress at the Presbyterian church in Upper Alton on October 26, 1837. The supporters in attendance were surprised to see two pro-slavery advocates in the crowd, John Hogan and Illinois Attorney General Usher F. Linder. The Lovejoy supporters were not happy to have his enemies at the convention, but relented as the meeting was open to all parties.[17]

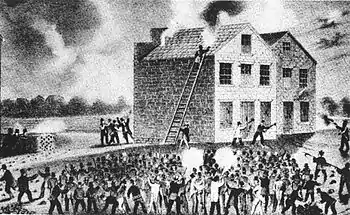

On November 7, 1837, pro-slavery partisans approached Gilman's warehouse, where Lovejoy had hidden his printing press.[18][19] According to the Alton Observer, the mob fired shots into the warehouse. When Lovejoy and his men returned fire, they hit several people in the crowd, killing a man named Bishop.[18]

The leaders of the mob set up a ladder against the warehouse. They sent a boy up with a torch to set fire to the wooden roof. Lovejoy and his supporter Royal Weller went outside, surprised the pro-slavery partisans, pushed over the ladder and retreated back inside the warehouse. The mob put up the ladder again; when Lovejoy and Weller went out to overturn it, they were spotted and shot. Lovejoy was hit five times with slugs from a shotgun and died immediately; Weller was wounded. The mob destroyed the new printing press by carrying it to a window and throwing it out onto the riverbank. They broke it up and threw the pieces into the river.

After his death, his brother Owen Lovejoy entered politics and became the leader of the Illinois abolitionists. Francis Butter Murdoch, the district attorney of Alton, prosecuted Lovejoy's murder but no one was convicted. The jury foreman had been a member of the mob and was wounded in the attack. The presiding judge also doubled as a witness to the proceedings. These conflicts of interest resulted in a "not guilty" verdict.[13]

Lovejoy was considered a martyr by the abolition movement. In his name, his brother Owen became the leader of the Illinois abolitionists. Owen and his brother Joseph wrote a memoir about Elijah, which was published in 1838 by the Anti-Slavery Society in New York and distributed widely among abolitionists in the nation. With his murder symbolic of the rising tensions within the country, Lovejoy is called the "first casualty of the Civil War."[15]

Elijah Lovejoy was buried in Alton Cemetery in an unmarked grave. In 1860, Thomas Dimmock, editor of the Alton Democrat, located the grave and arranged for a proper grave marker. Some of his supporters were later buried near him.

On November 2, 1837, five days before his death, he gave an emotive speech in Alton on the abolition question. In it, he asserted his willingness to respect the views of his opponents, but claimed the right to challenge them, as guaranteed in the Constitution. He reminded the audience that he was a hardworking and God-fearing citizen who had broken no laws, and that the physical threats to him and his family were totally unjustified. He ended by declaring that he would not be driven away, but would continue his work in Alton.[20]

There was such fear at the time of Lovejoy's death that no service was held, and the town newspaper he had led did not even report his death, though many other newspapers around the country decried this murder. The 1837 mob killing of Elijah Lovejoy was finally commemorated by a monument in Alton's City Cemetery, installed sixty years later in 1897. Another sixty years passed before John Glanville Gill published the first full-length biography of the slain abolitionist minister and editor. Gill was himself a former Alton minister who, like Lovejoy, also suffered persecution for his commitment to human rights.

Legacy and honors

- 1838, his brothers Joseph C. and Owen Lovejoy wrote a memoir about him and his defense of the free press, which they published in New York, under the title: Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy: Who was Murdered in Defence of the Liberty of the Press at Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837

- Abraham Lincoln referenced Lovejoy's murder in his Lyceum address in January 1838.

- John Brown was inspired by Lovejoy's death, declaring in church, "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery."[21]

- In 1897, Alton citizens erected the 110-foot tall Elijah P. Lovejoy Monument at the cemetery where he was buried.

- John Glanville Gill completed his Ph.D. at Harvard in 1946 on The Issues Involved in the Death of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy, Alton, 1837.[22] This thesis was later turned into a book, the first biography of Elijah Parish Lovejoy, entitled "Tide Without Turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the Press".

- The majority African-American village of Brooklyn, Illinois, located just north of East St. Louis, is popularly known as Lovejoy in his honor.

- The Lovejoy Library at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville is named in his honor; some had proposed naming the university after him.

- The Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award was established by Colby College in his honor, and is awarded annually to a member of the newspaper profession who "has contributed to the nation's journalistic achievement." A major classroom building at Colby is also named for Lovejoy. Furthermore, an inscribed memorial rock from his birthplace occupies a prominent position in a grassy square at Colby.

- Elijah Lovejoy is recognized by a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[23]

- In 2003, Reed College established the Elijah Parish and Owen Lovejoy Scholarship, which it awards annually.

- His descendant, Martha Lovejoy, is a supervisor in the U.S. State Department's Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, which coordinates the United States Government's efforts to combat modern forms of slavery.

- There is a Lovejoy Elementary School in Alton, IL.

- There is a Lovejoy Health Center named for him in Albion, ME, the place of his birth.

- There is a plaque honoring Elijah Parish Lovejoy on the external wall at the Mackay Campus Center at his alma mater, Princeton Theological Seminary.

- The Lovejoy School in Washington, DC was named in his honor in 1870. It closed in 1988 and became the Lovejoy Lofts condominiums in 2004.

- The Presbytery of Giddings-Lovejoy, Presbyterian Church (USA), formed from the merger of Elijah Parish Lovejoy Presbytery and the Presbytery of Southeast Missouri on January 3, 1985.[16]

- Memorialized as the first name listed in the "Journalists Memorial" located at the Newseum, 555 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC.[24][25]

- College Avenue Presbyterian Church (formerly Upper Alton Presbyterian), which was founded by Elijah Lovejoy, merged with United Presbyterian Church in Wood River, IL in 2016. The church is now named LoveJoy United Presbyterian Church, after its founder.

See also

- Censorship in the United States

- List of journalists killed in the United States

- List of unsolved murders

References

Notes

- Brown, Justus Newton (September–October 1916). "Lovejoy's Influence on John Brown". Magazine of History with Notes and Queries. 23 (3–4). pp. 97–102.

- Lawson and Howard, p528.

- Dillon, p3.

- Lovejoy and Lovejoy, pp. 18–19.

- Dillon, p5.

- Lovejoy and Lovejoy, p. 23

- Dillon, p6.

- Dillon, p7.

- Dillon, p9.

- Dillon, p10.

- Dillon, p11.

- Brown, William W. (1847). Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, written by himself. Boston.

- Van Ravenswaay, Charles (1991). St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764-1865. Missouri History Museum.

- Balmer, p. 346.

- John Glanville Gill, Tide Without Turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the Press (1958).

- "Reverend Elijah Parish Lovejoy". Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Simon, Paul (1994). Freedom's Champion: Elijah Lovejoy (Rev. ed.). Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-8093-1941-1.

- "Winthrop S. Gilman Dead: An Original Abolitionist and Successful Business Man and Banker". The New York Times. 1884-10-05.

Winthrop Sargent Gilman, head of the banking house of Gilman, Son Co., of No. 62 Cedar-street, this city, died at his Summer home in Palisades, Rockland County, N.Y., on Friday, age 76. Mr. Gilman was known as a business ...

- "Elijah Parish Lovejoy Was Killed By a Pro-slavery Mob". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

On November 7, 1837, Elijah Parish Lovejoy was killed by a pro-slavery mob while defending the site of his anti-slavery newspaper, The Saint Louis Observer.

- Joseph P. and Owen Lovejoy, The Martyrdom of Lovejoy, An Account of the Life, Trials, and Perils of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy (1838).

- "Biography of John Brown". War and Reconciliation: The Mid-Missouri Civil War Project. University of Missouri-Columbia School of Law. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- John Glanville Gill. The issues involved in the death of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy, Alton, 1837, Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, 1946

- St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Rosenwald, Michael S. (June 29, 2018). "Angry mobs, deadly duels, presses set on fire: A history of attacks on the press". Washington Post.

- http://www.newseum.org/exhibits/online/journalists-memorial/

Bibliography

- Beecher, Edward (1969). Narrative of Riots at Alton, in Connection with the Death of Rev. Elijah P Lovejoy. Mnemosyne Pub. Co.

- Dillon, Merton L. (1999). John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (ed.). American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. Vol. 14, pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-19-512793-5.

- Dillon, Merton L. (1961). Elijah P. Lovejoy, Abolitionist Editor. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Gill, John Glanville (1959). Tide Without Turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the Press. Boston: Starr King Press.

- Lawson, John D. (1916). Robert L. Howard (ed.). American State Trials: A Collection of the Important and Interesting Criminal Trials which have taken place in the United States, from the beginning of our Government to the Present Day. St. Louis: F. H. Thomas Law Book Co.

- Lovejoy, Joseph C.; Owen Lovejoy (1838). Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy: Who was Murdered in Defence of the Liberty of the Press at Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837. New York: J. S. Taylor.

memoir of the rev elijah p lovejoy.

- Tanner, Henry (1971). The Martyrdom of Lovejoy: An Account of the Life, Trials, and Perils of Rev Elijah P. Lovejoy. A. M. Kelley. ISBN 0-678-00744-6.

Further reading

- Dinius, Marcy J. (2018). "Press". Early American Studies. 16 (4): 747–755. doi:10.1353/eam.2018.0045 – via Project MUSE.

- Phillips, Jennifer (2009). Elijah Lovejoy's Fight for Freedom. Publisher: Nose in a Book Publishing. Biography for middle-grade readers.

- Simon, Paul (1994). Freedom's Champion: Elijah Lovejoy. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-1940-3.

- Alton trials : of Winthrop S. Gilman, who was indicted with Enoch Long, Amos B. Roff, George H. Walworth, William Harned, John S. Noble, James Morss, Jr., Henry Tanner, Royal Weller, Reuben Gerry, and Taddeus B. Hurlbut; for the crime of riot, Committed on the night of the 7th of November, 1837, while engaged in defending a printing press, from an attack made on it at that time, by an armed mob. Written out from notes of the trial, taken at the time, by a member of the bar of the Alton Municipal Court. Also, the trial of John Solomon, Levi Palmer, Horace Beall, Josiah Nutter, Jacob Smith, David Butler, William Carr, and James M. Rock, indicted with James Jennings, Solomon Morgan, and Frederick Bruchy; for a riot committed in Alton, On the night of the 7th of November, 1837, in unlawfully and forcibly entering the Warehouse of Godfrey, Gilman & Co., and breaking up and destroying a printing press. Written out from notes taken at the time of trial, by William S. Lincoln, A Member of the Bar of the Alton Municipal Court. New-York: John F. Trow. 1838.

External links

- Biography from Spartacus Educational

- St. Louis Walk of Fame

- Biography from the Alton, Illinois web

- Correspondence & manuscripts, 1804-1891, at Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University See also papers of nephew Austin Wiswall, officer with 9th US Colored Troops, captured and held at Andersonville.

- Frontenac, Missouri meetinghouse where Lovejoy once preached

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Elijah Parish Lovejoy at Find a Grave