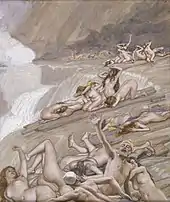

List of flood myths

Flood myths are common across a wide range of cultures, extending back into Bronze Age and Neolithic prehistory. These accounts depict a flood, sometimes global in scale, usually sent by a deity or deities to destroy civilization as an act of divine retribution.

Africa

Although the continent has relatively few flood legends,[1][2][3][4] African cultures preserving an oral tradition of a flood include the Kwaya, Mbuti, Maasai, Mandin, and Yoruba peoples.[5]

Egypt

The flood myth in Egyptian mythology involves the god Ra and his daughter Sekhmet. Ra sent Sekhmet to destroy part of humanity for their disrespect and unfaithfulness which resulted in a great flood of blood. However, Re intervened by getting her drunk and causing her to pass out. This is commemorated in a wine drinking festival during the annual Nile flood.[6]

Americas

North America

- Choctaw: A Choctaw Flood Story[7]

- Ojibwe: Great Serpent and the Great Flood[8]

- Ojibwe: Manabozho and the Muskrat[8]

- Ojibwe: Waynaboozhoo and the Great Flood[8]

- Menomini: Manabozho and the Flood[8]

- Other Algonquin-speaking peoples: Manabozho Stories[8]

- Mi'kmaq: Two Creators and their Conflicts[8]

- Anishinabe: Flood Myth - an Algonquin Story[8]

- Ottawa: The Great Flood[8]

- Cree: Cree Flood Story[8]

- Cree (Knisteneaux): Knisteneaux Flood Myth

- Nipmuc: Cautanowwit[8]

- Hopi mythology: Entrance into the Fourth World

- W̱SÁNEĆ peoples: flood myth [9]

- Comox people: Legend of Queneesh

- Anishinaabe: Turtle Island [10]

- Inuit: flood myth[11]

- Nisqually - In the beginning of the Nisqually world. [12]

- Eskimo (Orowignarak, Alaska): "A great inundation, together with an earthquake, swept the land so rapidly that only a few people escaped in their skin canoes to the tops of the highest mountains."[13]

Mesoamerica

Canari

Inca

Muisca

Tupi

Asia

Sumerian

Mesopotamia

Abrahamic religions

India

- Manu and Matsya: The legend first appears in Shatapatha Brahmana (700–300 BCE), and is further detailed in Matsya Purana (250–500 CE). Matsya (the incarnation of Lord Vishnu as a fish) forewarns Manu (a human) about an impending catastrophic flood and orders him to collect all the grains of the world in a boat; in some forms of the story, all living creatures are also to be preserved in the boat. When the flood destroys the world, Manu – in some versions accompanied by the seven great sages – survives by boarding the ark, which Matsya pulls to safety.

- Puluga, the creator god in the religion of the indigenous inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, sends a devastating flood to punish people who have forgotten his commands. Only four people survive this flood: two men and two women.

Korea

Malaysia

Philippines

- Igorot: Once upon a time, when the world was flat and there were no mountains, there lived two brothers, sons of Lumawig, the Great Spirit. The brothers were fond of hunting, and since no mountains had formed there was no good place to catch wild pig and deer, and the older brother said: "Let us cause water to flow over all the world and cover it, and then mountains will rise up."[16]

Thailand

There are many folktales among Tai peoples, included Zhuang, Thai, Shan and Lao, talking about the origin of them and the deluge from their Thean (แถน), supreme being object of faith.

- Pu Sangkasa-Ya Sangkasi (Thai: ปู่สังกะสา-ย่าสังกะสี) or Grandfather Sangkasa and Grandmother Sangkasi, according to the creation myth of those Tai people folktales, were the first man and woman created by the supreme god, Phu Ruthua (ผู้รู้ทั่ว). A thousand years passed, their descendants were wicked and crude as well as not interested in worshiping the supreme god. The god got angry and punished them with a great flood. Fortunately, some descendants survived because they fled into an enormous magical gourd. Many months passed, the supreme god had compassion on the humans that had to live in the difficult period of their life, so he had two deities Khun Luang and Khun Lai climbed down a massive vine linking an island heaven that floated in the sky to the earth in order to drill the enormous gourd and take the surviving humans to a new land. The water levels had been come down already and there was the dry land. The deities helped the surviving people and led them to the new land. When everyone arrived in the land called Mueang Thaen, the two deities taught the humans how to cultivate rice, farming and building structures. [17]

Taiwan's Saisiat Tribe

An old white-haired man came to Oppehnaboon in a dream and told him that a great storm would soon come. Oppehnaboon built a boat. Only Oppehnaboon and his sister survived. They had a child, they cut the child into pieces and each piece became a new person. Oppehnaboon taught the new people their names and they went forth to populate the earth.

Europe

Classical Antiquity

Norse

Bashkir

Finnish

References

- Witzel, E.J. Michael (2012). The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford University Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-19971-015-7.

- Witzel, E.J. Michael (2012). The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-19971-015-7.

- Martinez, Susan B. (2016). The Lost Continent of Pan: The Oceanic Civilization at the Origin of World Culture. Simon and Schuster. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-59143-268-5.

- Gerland, Georg (1912). Der Mythus von der Sintflut. Bonn: A. Marcus und E. Webers Verlag. p. 209. ISBN 978-3-95913-784-3.

- Lynch, Patricia (2010). African Mythology, A to Z. Chelsea House. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-60413-415-5.

- McDonald, Logan (2018). "Worldwide Waters: Laurasian Flood Myths andTheir Connections". georgiasouthern.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Choctaw Legends". Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- "Native American Indian Flood Myths". www.native-languages.org. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- SENĆOŦENStory – ȽÁUWELṈEW, FirstVoices.com

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2015-11-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Grand Council Treaty #3, The Government of the Anishinaabe Nation in Treaty #3

- "Flood Stories from Around the World". www.talkorigins.org.

- In The Beginning of the Nisqually World

- Orowignarak flood myth at talkorigins.org

- "Jipohan é gente como você". Povos Indígenas no Brasil (in Portuguese). 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Crépeau, Robert R. (October 1997). "Mito e ritual entre os índios Kaingang do Brasil meridional". Horizontes Antropológicos. 3 (6): 173–186. doi:10.1590/s0104-71831997000200009.

- "Philippine Folk Tales: Igorot: The Flood Story". www.sacred-texts.com.

- Na Thalang, Siriporn (1996). การวิเคราะห์ตำนานสร้างโลกของคนไท : รายงานการวิจัย. Chulalongkorn University.