Andaman Islands

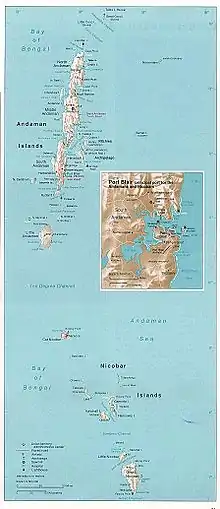

The Andaman Islands is an archipelago in the northeastern Indian Ocean about 130 km (81 mi) southwest off the coasts of Myanmar's Ayeyarwady Region. Together with the Nicobar Islands to their south, the Andamans serve as a maritime boundary between the Bay of Bengal to the west and the Andaman Sea to the east. Most of the islands are part of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a Union Territory of India, while the Coco Islands and Preparis Island in the archipelago's north belong to Myanmar.

Andaman Islands Location of the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean  Andaman Islands Andaman Islands (Bay of Bengal)  Andaman Islands Andaman Islands (India) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Bay of Bengal |

| Coordinates | 12°30′N 92°45′E |

| Archipelago | Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

| Total islands | 572 |

| Major islands | North Andaman Island, Little Andaman, Middle Andaman Island, South Andaman Island |

| Area | 6,408 km2 (2,474 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 732 m (2402 ft) |

| Highest point | Saddle Peak |

| Administration | |

India | |

| Union territory | Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

| Capital city | Port Blair |

Myanmar | |

| Administrative region | Yangon Region |

| Capital | Yangon |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 343,125 (2011) |

| Pop. density | 48/km2 (124/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Bamar Mainland Indians Jarawa Onge Sentinelese Great Andamanese |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| • Summer (DST) |

|

| Official website | www |

The Andaman Islands are home to the Andamanese, a group of indigenous people that includes a number of tribes, including the Jarawa and Sentinelese tribes.[1] While some of the islands can be visited with permits, entry to others, including North Sentinel Island, is banned by law. The Sentinelese are generally hostile to visitors and have had little contact with any other people. The government protects their right to privacy.[2]

History

Etymology

The origin of the name Andaman is disputed and not well known.

In the 13th century, the name of Andaman appears in Chinese as Yen-to-man (晏陀蠻) in the book Zhu Fan Zhi by Zhao Rugua.[3] In Chapter 38 of the book, Countries in the Sea, Zhao Rugua specifies that going from Lambri (Sumatra) to Ceylon, it is an unfavourable wind which makes ships drift towards Andaman Islands.[3][4] In the 15th century, Andaman was recorded as "An-de-man mountain" (安得蛮山) during the voyages of Zheng He in the Mao Kun map of the Wu Bei Zhi.[5]

Early inhabitants

The earliest archaeological evidence yet documented goes back some 2,200 years; however, the indications from genetic, cultural and isolation studies suggest that the islands may have been inhabited as early as the Middle Paleolithic ( around 60,000 years ago ).[6] The indigenous Andamanese peoples appear to have lived on the islands in substantial isolation from that time until the late 18th century.

Chola empire

Rajendra Chola (1014 to 1042 AD) took over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[7]

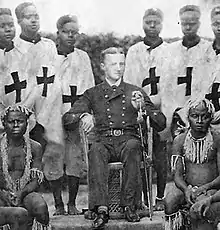

British colonisation

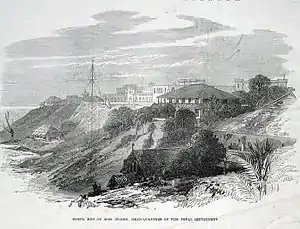

In 1789, the Bengal Presidency established a naval base and penal colony on Chatham Island in the southeast bay of Great Andaman. The settlement is now known as Port Blair (after the Bombay Marine lieutenant Archibald Blair who founded it). After two years, the colony was moved to the northeast part of Great Andaman and was named Port Cornwallis after Admiral William Cornwallis. However, there was much disease and death in the penal colony and the government ceased operating it in May 1796.[8][9]

In 1824, Port Cornwallis was the rendezvous of the fleet carrying the army to the First Burmese War.[10] In the 1830s and 1840s, shipwrecked crews who landed on the Andamans were often attacked and killed by the natives and the islands had a reputation for cannibalism. The loss of the Runnymede and the Briton in 1844 during the same storm, while transporting goods and passengers between India and Australia, and the continuous attacks launched by the natives, which the survivors fought off, alarmed the British government.[11] In 1855, the government proposed another settlement on the islands, including a convict establishment, but the Indian Rebellion of 1857 forced a delay in its construction. However, because the rebellion gave the British so many prisoners, it made the new Andaman settlement and prison urgently necessary. Construction began in November 1857 at Port Blair using inmates' labour, avoiding the vicinity of a salt swamp that seemed to have been the source of many of the earlier problems at Port Cornwallis.

17 May 1859 was another major day for Andaman. The Battle of Aberdeen was fought between the Great Andamanese tribe and the British. Today, a memorial stands in Andaman water sports complex as a tribute to the people who lost their lives. Fearing foreign invasion and with help from an escaped convict from Cellular Jail, the Great Andamanese stormed the British post, but they were outnumbered and soon suffered heavy loss of life. Later, it was identified that an escaped convict named Doodnath had changed sides and informed the British about the tribe's plans. Today, the tribe has been reduced to some 50 people, with less than 50% of them adults. The government of the Andaman Islands is making efforts to increase the headcount of this tribe.[12] [13][14]

In 1867, the ship Nineveh wrecked on the reef of North Sentinel Island. The 86 survivors reached the beach in the ship's boats. On the third day, they were attacked with iron-tipped spears by naked islanders. One person from the ship escaped in a boat and the others were later rescued by a British Royal Navy ship.[15]

For some time, sickness and mortality were high, but swamp reclamation and extensive forest clearance continued. The Andaman colony became notorious with the murder of the Viceroy Richard Southwell Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo, on a visit to the settlement (8 February 1872), by a Pathan from Afghanistan, Sher Ali Afridi. In the same year, the two island groups Andaman and Nicobar, were united under a chief commissioner residing at Port Blair.[10]

From the time of its development in 1858 under the direction of James Pattison Walker, and in response to the mutiny and rebellion of the previous year, the settlement was first and foremost a repository for political prisoners. The Cellular Jail at Port Blair, when completed in 1910, included 698 cells designed for solitary confinement; each cell measured 4.5 by 2.7 m (15 by 9 ft) with a single ventilation window 3 metres (10 ft) above the floor.

The Indians imprisoned here referred to the island and its prison as Kala Pani ("black water");[16] a 1996 film set on the island took that term as its title, Kaalapani.[17] The number of prisoners who died in this camp is estimated to be in the thousands.[18] Many more died of harsh treatment and the harsh living and working conditions in this camp.[19]

The Viper Chain Gang Jail on Viper Island was reserved for troublemakers, and was also the site of hangings. In the 20th century, it became a convenient place to house prominent members of India's independence movement.

Japanese occupation

The Andaman and Nicobar islands were occupied by Japan during World War II.[20] The islands were nominally put under the authority of the Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind (Provisional Government of Free India) headed by Subhas Chandra Bose, who visited the islands during the war, and renamed them as Shaheed (Martyr) & Swaraj (Self-rule). On 30 December 1943, during the Japanese occupation, Bose, who was allied with the Japanese, first raised the flag of Indian independence. General Loganathan, of the Indian National Army, was Governor of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which had been annexed to the Provisional Government. According to Werner Gruhl: "Before leaving the islands, the Japanese rounded up and executed 750 innocents."[21]

Since World War II

At the close of World War II, the British government announced its intention to abolish the penal settlement. The government proposed to employ former inmates in an initiative to develop the island's fisheries, timber, and agricultural resources. In exchange, inmates would be granted return passage to the Indian mainland, or the right to settle on the islands. J H Williams, one of the Bombay Burma Company's senior officials, was dispatched to perform a timber survey of the islands using convict labor. He recorded his findings in 'The Spotted Dear' (1957).

The penal colony was eventually closed on 15 August 1947 when India gained independence. It has since served as a museum to the independence movement.[22]

Most of the Andaman Islands became part of India in 1950 and was declared as a union territory of the nation in 1956, while the Preparis Island and Coco Islands became part of the Yangon Region of Myanmar in 1948.[23]

In April 1998, American photographer John S Callahan organised the first surfing project in the Andamans, starting from Phuket in Thailand with the assistance of Southeast Asia Liveaboards (SEAL), a UK owned dive charter company. With a crew of international professional surfers, they crossed the Andaman Sea on the yacht Crescent and cleared formalities in Port Blair. The group proceeded to Little Andaman Island, where they spent ten days surfing several spots for the first time, including Jarawa Point near Hut Bay and the long right reef point at the southwest tip of the island, named Kumari Point. The resulting article in Surfer Magazine, "Quest for Fire" by journalist Sam George, put the Andaman Islands on the surfing map for the first time.[24] Footage of the waves of the Andaman Islands also appeared in the film Thicker than Water, shot by documentary filmmaker Jack Johnson, who later achieved worldwide fame as a popular musician. Callahan went on to make several more surfing projects in the Andamans, including a trip to the Nicobar Islands in 1999.

On 26 December 2004, the coast of the Andaman Islands was devastated by a 10-metre-high (33 ft) tsunami following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, which is the longest recorded earthquake, lasting for between 500 and 600 seconds.[25] Strong oral traditions in the area warned of the importance of moving inland after a quake and is credited with saving many lives. In the aftermath, more than 2,000 people were confirmed dead and more than 4,000 children were orphaned or had lost one parent. At least 40,000 residents were rendered homeless and were moved to relief camps.[26] On 11 August 2009, a magnitude 7 earthquake struck near the Andaman Islands, causing a tsunami warning to go into effect. On 30 March 2010, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake struck near the Andaman Islands.

In November 2018, John Allen Chau, an American missionary, traveled illegally with the help of local fishermen to the North Sentinel Island of the Andaman Islands chain group on several occasions, despite a travel ban to the island. He is reported to have been killed.[27] A 2018 Restricted Area Permit (RAP) regime relaxed the prohibition on visiting islands in the area, but this plan was intended only to allow researchers and anthropologists, with pre-approved clearance, to visit the Sentinel islands. Chau had no such clearance and knew that his visit was illegal.[28][27]

According to the immigration officials at Port Blair airport, citizens of China, Pakistan and Afghanistan are not allowed into the Andaman Islands including USA passport holders who were born in those three countries. Dated 15 Jan 2020.

Geography

The Andaman Archipelago is an oceanic continuation of the Burmese Arakan Yoma range in the North and of the Indonesian Archipelago in the South. It has 325 islands which cover an area of 6,408 km2 (2,474 sq mi),[29] with the Andaman Sea to the east between the islands and the coast of Burma.[9] North Andaman Island is 285 kilometres (177 mi) south of Burma, although a few smaller Burmese islands are closer, including the three Coco Islands.

The Ten Degree Channel separates the Andamans from the Nicobar Islands to the south. The highest point is located in North Andaman Island (Saddle Peak at 732 m (2,402 ft)).[29]:33

The subsoil of the Andaman islands consists essentially of Late Jurassic to Early Eocene ophiolites and sedimentary rocks (argillaceous and algal limestones), deformed by numerous deep faults and thrusts with ultramafic igneous intrusions.[30] There are at least 11 mud volcanoes on the islands.[30]

The climate is typical of tropical islands of similar latitude. It is always warm, but with sea-breezes. Rainfall is irregular, usually dry during the north-east monsoons, and very wet during the south-west monsoons.[31]

Flora

The Middle Andamans harbour mostly moist deciduous forests. North Andamans is characterised by the wet evergreen type, with plenty of woody climbers.

The natural vegetation of the Andamans is tropical forest, with mangroves on the coast. The rainforests are similar in composition to those of the west coast of Burma. Most of the forests are evergreen, but there are areas of deciduous forest on North Andaman, Middle Andaman, Baratang and parts of South Andaman Island. The South Andaman forests have a profuse growth of epiphytic vegetation, mostly ferns and orchids.

The Andaman forests are largely unspoiled, despite logging and the demands of the fast-growing population driven by immigration from the Indian mainland. There are protected areas on Little Andaman, Narcondam, North Andaman and South Andaman, but these are mainly aimed at preserving the coast and the marine wildlife rather than the rainforests.[32] Threats to wildlife come from introduced species including rats, dogs, cats and the elephants of Interview Island and North Andaman.

Timber

Andaman forests contain 200 or more timber producing species of trees, out of which about 30 varieties are considered to be commercial. Major commercial timber species are Gurjan (Dipterocarpus spp.) and Padauk (Pterocarpus dalbergioides). The following ornamental woods are noted for their pronounced grain formation:

- Marble wood (Diospyros marmorata)

- Padauk (Pterocarpus dalbergioides)

- Silver grey (a special formation of wood in white utkarsh)

- Chooi (Sageraea elliptica)

- Kokko (Albizzia lebbeck)

Padauk wood is sturdier than teak and is widely used for furniture making.

There are burr wood and buttress root formations in Andaman Padauk. The largest piece of buttress known from Andaman was a dining table of 13 ft × 7 ft (4.0 m × 2.1 m). The largest piece of burr wood was again a dining table for eight.

The Rudraksha (Elaeocarps sphaericus) and aromatic Dhoop-resin trees also are found here.

Fauna

The Andaman Islands are home to a number of animals, many of them endemic. Andaman & Nicobar islands are home to 10% of all Indian fauna species.[33] The islands by ratio is only 0.25% of country's geographical area, has 11,009 species, according to a publication by the Zoological Survey of India.[33]

Mammals

The island's endemic mammals include

- Andaman spiny shrew (Crocidura hispida)

- Andaman shrew (Crocidura andamanensis)

- Jenkins's shrew (Crocidura jenkinsi)

- Andaman horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus cognatus)

- Andaman rat (Rattus stoicus)

The banded pig (Sus scrofa vittatus), also known as the Andaman wild boar and once thought to be an endemic subspecies,[34] is protected by the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 (Sch I). The spotted deer (Axis axis), the Indian muntjac (Muntiacus muntjak) and the sambar (Rusa unicolor) were all introduced to the Andaman islands, though the sambar did not survive.

Interview Island (the largest wildlife sanctuary in the territory) in Middle Andaman holds a population of feral elephants, which were brought in for forest work by a timber company and released when the company went bankrupt. This population has been subject to research studies.

Birds

Endemic or near endemic birds include

- Spilornis elgini, a serpent-eagle

- Rallina canningi, a crake (endemic; data-deficient per IUCN 2000)

- Columba palumboides, a wood-pigeon

- Macropygia rufipennis, a cuckoo dove

- Centropus andamanensis, a subspecies of brown coucal (endemic)

- Otus balli, a scops owl

- Ninox affinis, a hawk-owl

- Rhyticeros narcondami, the Narcondam hornbill

- Dryocopus hodgei, a woodpecker

- Dicrurus andamanensis, a drongo

- Dendrocitta bayleyii, a treepie

- Sturnus erythropygius, the white-headed starling

- Collocalia affinis, the plume-toed swiftlet

- Aerodramus fuciphagus, the edible-nest swiftlet

The islands' many caves, such as those at Chalis Ek are nesting grounds for the edible-nest swiftlet, whose nests are prized in China for bird's nest soup.[35]

Reptiles and amphibians

The islands also have a number of endemic reptiles, toads and frogs, such as the Andaman cobra (Naja sagittifera), South Andaman krait (Bungarus andamanensis) and Andaman water monitor (Varanus salvator andamanensis).

There is a sanctuary 72 km (45 mi) from Havelock Island for saltwater crocodiles. Over the past 25 years there have been 24 crocodile attacks with four fatalities, including the death of American tourist Lauren Failla. The government has been criticised for failing to inform tourists of the crocodile sanctuary and danger, while simultaneously promoting tourism.[36] Crocodiles are not only found within the sanctuary, but throughout the island chain in varying densities. They are habitat restricted, so the population is stable but not large. Populations occur throughout available mangrove habitat on all major islands, including a few creeks on Havelock. The species uses the ocean as a means of travel between different rivers and estuaries, thus they are not as commonly observed in open ocean. It is best to avoid swimming near mangrove areas or the mouths of creeks; swimming in the open ocean should be safe, but it is best to have a spotter around.

Religion

Most of the tribal people in Andaman and Nicobar Islands believe in a religion that can be described as a form of monotheistic Animism. The tribal people of these islands believe that Paluga is the only deity and is responsible for everything happening on Earth.[37] The faith of the Andamanese teaches that Paluga resides on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands' Saddle Peak. People try to avoid any action that might displease Paluga. People belonging to this religion believe in the presence of souls, ghosts, and spirits. People of this religion put a lot of emphasis on dreams. They let dreams decide different courses of action in their lives.[38]

Other religions practiced in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are, in order of size, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism and Baháʼí Faith.[39][40]

Demographics

As of 2011, the population of the Andaman was 343,125,[41] having grown from 50,000 in 1960. The bulk of the population originates from immigrants who came to the island since the colonial times, mainly of Bengali, Hindustani and Tamil backgrounds.[42]

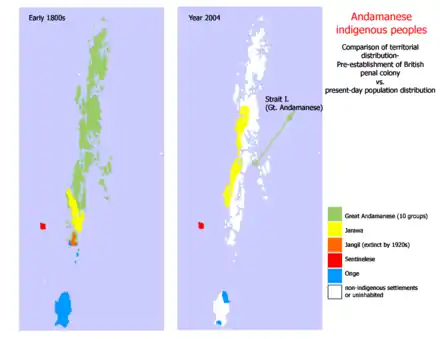

A small minority of the population are the Andamanese — the aboriginal inhabitants (adivasi) of the islands. When they first came into sustained contact with outside groups in the 1850s, there were an estimated 7,000 Andamanese, divided into the Great Andamanese, Jarawa, Jangil (or Rutland Jarawa), Onge, and the Sentinelese. The Great Andamanese formed 10 tribes of 5,000 people total.

As the numbers of settlers from the mainland increased (at first mostly prisoners and involuntary indentured labourers, later purposely recruited farmers), these indigenous people lost territory and numbers in the face of punitive expeditions by British troops, land encroachment and various epidemic diseases.

Presently, there remain only approximately 400–450 indigenous Andamanese. The Jangil are extinct. Most of the Great Andamanese tribes are extinct, and the survivors, now just 52, speak mostly Bengali.[43] The Onge are reduced to less than 100 people. Only the Jarawa and Sentinelese still maintain a steadfast independence and refuse most attempts at contact; their numbers are uncertain but estimated to be in the low hundreds.

Government

Port Blair is the chief community on the islands, and the administrative centre of the Union Territory. The Andaman Islands form a single administrative district within the Union Territory, the Andaman district (the Nicobar Islands were separated and established as the new Nicobar district in 1974).

Cultural references

The islands are prominently featured in Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes 1890 mystery The Sign of the Four. The magistrate in Lady Gregory's play Spreading the News had formerly served in the islands.

M. M. Kaye's 1985 novel Death in the Andamans and Marianne Wiggins' 1989 novel John Dollar are set in the islands. The latter begins with an expedition from Burma to celebrate King George's birthday, but turns into a grim survival story after an earthquake and tsunami. Priyadarshan's 1996 film Kaalapani (Malayalam; Sirai Chaalai in Tamil) depicts the Indian freedom struggle and the lives of prisoners in the Cellular Jail in Port Blair. Island's End is a 2011 novel by Padma Venkatraman about the training of an indigenous shaman. A principal character in the novel Six Suspects by Vikas Swarup is from the Andaman Islands.

Brodie Moncur, the main protagonist of William Boyd's 2018 novel Love is Blind, spends time in the Andaman Islands in the early years of the 20th century.

Transportation

The only commercial airport in the islands is Veer Savarkar International Airport in Port Blair, which has scheduled services to Kolkata, Chennai, New Delhi, Bengaluru and Visakhapatnam. The airport is under the control of the Indian Navy. Prior to 2016 only daylight operations were allowed; however, since 2016 night flights have also operated.[44] A small airstrip, about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) long, is located near the eastern shore of North Andaman near Diglipur.

Due to the length of the routes and the small number of airlines flying to the islands, fares have historically been relatively expensive, although cheaper for locals than visitors. Fares are high during the peak seasons of spring and winter, although fares have decreased over time due to the expansion of the civil aviation industry in India. Private flights are also allowed to land in Port Blair airport with prior permission.

There is also a ship service from Chennai, Visakhapatnam and Kolkata. The journey requires three days and two nights, and depends on weather.

See also

References

Notes

- "Police face-off with Sentinelese tribe as they struggle to recover slain missionary's body". News.com.au. 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Andaman & Nicobar". The Internet Archive. A&N Administration. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Chau Ju-kua: His Work on the Chinese And Arab Trade in the Twelfth And Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-fan-chï. Translated by Friedrich Hirth; William Woodville Rockhill. St. Petersburg, Printing office of the Imperial academy of sciences. 1911. p. 147.

When sailing from lan-wu-li to si-lan, if the wind is not fair, ships maybe driven to a place called Yen-to-man. This is a group of two islands in the middle of the sea, one of them being large, the other small; the latter is quite uninhabited. ... The natives on it are of a colour resmbling black lacquer; they eat men alive, so that sailors dare not anchor on this coast.

- Cordier, Henri; Yule, Henry (1920). Ser Marco Polo : notes and addenda to Sir Henry Yule's edition, containing the results of recent research and discovery. London: John Murray. p. 109.

- "Wu Bei Zhi Map 17". Library of Congress.

- Palanichamy, M. G.; Agrawal, S; Yao, Y. G.; Kong, Q. P.; Sun, C; Khan, F; Chaudhuri, T. K.; Zhang, Y. P. (2006). "Comment on "Reconstructing the origin of Andaman islanders"". Science. 311 (5760): 470, author reply 470. doi:10.1126/science.1120176. PMID 16439647.

Andamanese, Tamil and Malayalam are the major languages spoken here

- Krishnan, Madhuvanti S. (4 May 2017). "Happy in HAVELOCK". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 957–958.

- Blaise, Olivier. "Andaman Islands, India". PictureTank. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Chisholm 1911, p. 958.

- Kingston, W.H.G. (1873) Shipwrecks and Disasters at Sea. George Routledge and Sons, London.

- "The Rise and Fall of the Great Andamanese". Confessions of a Linguist!. 8 April 2012.

- "Who are heroes of Battle of Aberdeen?". oneindia.com. 17 May 2007.

- sanjib (15 May 2012). "Tribute at the Memorial of "Battle of Aberdeen" Today". andamansheekha.com.

- "The Last Island of the Savages". American Scholar. 22 September 2000.

- "History of Andaman Cellular Jail". Andamancellularjail.org. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Kala Pani (1996)". Imdb.com. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Andaman Islands Political Prisoners". Andamancellularjail.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Opinion / News Analysis: Hundred years of the Andamans Cellular Jail". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 21 December 2005. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "The capture of the Andaman Islands, March 1942". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- Gruhl, Werner (2007) Imperial Japan's World War Two, 1931–1945, Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0352-8. p. 102.

- "How India's Cellular Jail was integral in the country's fight for freedom". The Independent. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- Planning Commission of India (2008). Andaman and Nicobar Islands Development Report. State Development Report series (illustrated ed.). Academic Foundation. ISBN 978-81-7188-652-4. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "Surfer Explores The Andaman Islands". Surfermag.com. Surfer Magazine. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness Book of World Records 2014. The Jim Pattison Group. pp. 015. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- Strand, Carl; Masek, John, eds. (2007). Sumatra-Andaman Islands Earthquake and Tsunami of December 26, 2004. Reston, VA: ASCE, Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering. ISBN 9780784409510. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- "Indian authorities struggle to retrieve US missionary feared killed on remote island". CNN. 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- "US National Defied 3-tier Curbs & Caution to Reach Island". The Times of India. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Planning Commission of India (2008). Andaman and Nicobar Islands Development Report. State Development Report series (illustrated ed.). Academic Foundation. ISBN 978-81-7188-652-4.

- Chakrabarti, P.; Nag, A.; Dutta, S. B.; Dasgupta, S. and Gupta, N. (2006) S & T Input: Earthquake and Tsunami Effects..., page 43. Chapter 5 in S. M. Ramasamy et al. (eds.), Geomatics in Tsunami, New India Publishing. ISBN 81-89422-31-6

- Chisholm 1911, p. 956.

- "Andaman Islands rain forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Singh, Shiv Sahay (25 November 2018). "Andaman & Nicobar Islands: home to a tenth of India's fauna species". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- Srinivasulu, C.; Srinivasulu, B. (2012). South Asian Mammals: Their Diversity, Distribution, and Status. Springer. p. 353. ISBN 9781461434498.

- Sankaran, R. (1998), The impact of nest collection on the Edible-nest Swiftlet in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Coimbatore, India.

- Sacks, Ethan (6 May 2010). "NJ woman killed by crocodile attack while snorkeling off Indian coast". NY Daily News.

- Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (14 November 2013). The Andaman Islanders. Cambridge University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-107-62556-3.

- "People of Andaman and Nicobar Islands". Webindia123.com. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- "Population by religious communities". censusindia.gov.in.

- Baháʼí. "Baháʼí Community of Andaman and Nicobar Islands". Baháʼí Community.

- "Andaman & Nicobar Islands". india.gov.in. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- "Andaman & Nicobar Islands at a glance". Andamandt.nic.in. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Malekar, Anosh (1 August 2011) "The case for a linguisitic survey," Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Infochange Media.

- Roy, Sanjib Kumar; Sheekha, Andaman, eds. (21 January 2016). "Maiden night flight arrives in Isles". Andaman Sheekha. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Andaman Islands". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 955–958.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Andaman Islands". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 955–958.- History & Culture. The Andaman Islands with destination quide

- India Home Dept (1859). The Andaman Islands: With Notes on Barren Island. C.B. Lewis, Baptist Mission Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Andaman Islands. |

- Official Andaman and Nicobar Tourism Website

- Sorenson, E. Richard (1993), "Sensuality and Consciousness:Psychosexual Transformation in the Eastern Andaman", Anthropology of Consciousness, 4 (4): 1–9, doi:10.1525/ac.1993.4.4.1

- Sen, Satadru (2009), "Savage Bodies, Civilized Pleasures: M. V. Portman and the Andamanese", American Ethnologist, 36 (2): 364–379, doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2009.01140.x