Nüwa

Nüwa is the mother goddess of Chinese mythology, the sister and wife of Fuxi, the emperor-god. She is credited with creating humanity and repairing the Pillar of Heaven.[1]

| Nüwa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

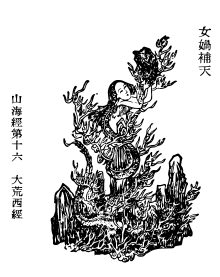

Nuwa repairing the pillar of heaven | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 女媧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 女娲 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Name

Chinese: 女; pinyin: nü; lit. 'female' is a common prefix of the names of goddesses. The proper name is Chinese: 媧; lit. 'wa'. The Chinese character is unique to this name. Birrell translates it as 'lovely', but notes that it "could be construed as 'frog', which is consistent with her aquatic myth."[2]

Her reverential name is Wahuang (Chinese: 媧皇; lit. 'Empress Wa').[3]

Description

The Huainanzi relates Nüwa to the time when Heaven and Earth were in disruption:

Going back to more ancient times, the four pillars were broken; the nine provinces were in tatters. Heaven did not completely cover [the earth]; Earth did not hold up [Heaven] all the way around [its circumference]. Fires blazed out of control and could not be extinguished; water flooded in great expanses and would not recede. Ferocious animals ate blameless people; predatory birds snatched the elderly and the weak. Thereupon, Nüwa smelted together five-colored stones in order to patch up the azure sky, cut off the legs of the great turtle to set them up as the four pillars, killed the black dragon to provide relief for Ji Province, and piled up reeds and cinders to stop the surging waters. The azure sky was patched; the four pillars were set up; the surging waters were drained; the province of Ji was tranquil; crafty vermin died off; blameless people [preserved their] lives.[4][lower-alpha 1]

The catastrophes were supposedly caused by the battle between the deities Gonggong and Zhuanxu (an event that was mentioned earlier in the Huainanzi),[lower-alpha 2] the five-colored stones symbolize the five Chinese elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water), the black dragon was the essence of water and thus cause of the floods, Ji Province serves metonymically for the central regions (the Sinitic world).[7] Following this, the Huainanzi tells about how the sage-rulers Nüwa and Fuxi set order over the realm by following the Way (道) and its potency (德).[4]

The Classic of Mountains and Seas, dated between the Warring States period and the Han Dynasty, describes Nüwa's intestines as being scattered into ten spirits.[8]

In Liezi (c. 475 – 221 BC), Chapter 5 "Questions of Tang" (卷第五 湯問篇), author Lie Yukou describes Nüwa repairing the original imperfect heaven using five-colored stones, and cutting the legs off a tortoise to use as struts to hold up the sky.

In the Songs of Chu (c. 340 – 278 BC), Chapter 3 "Asking Heaven" (Chinese: 问天), author Qu Yuan writes that Nüwa molded figures from the yellow earth, giving them life and the ability to bear children. After demons fought and broke the pillars of the heavens, Nüwa worked unceasingly to repair the damage, melting down the aforementioned stones to mend the heavens.

In Shuowen Jiezi (c. 58 – 147 AD), China's earliest dictionary, under the entry for Nüwa author Xu Shen describes her as being both the sister and the wife of Fuxi. Nüwa and Fuxi were pictured as having snake-like tails interlocked in an Eastern Han Dynasty mural in the Wuliang Temple in Jiaxiang county, Shandong province.

In Duyi Zhi (獨異志; c. 846 – 874 AD), Volume 3, author Li Rong gives this description.

Long ago, when the world first began, there were two people, Nü Kua and her older brother. They lived on Mount K'un-lun. And there were not yet any ordinary people in the world. They talked about becoming husband and wife, but they felt ashamed. So the brother at once went with his sister up Mount K'un-lun and made this prayer: "Oh Heaven, if Thou wouldst send us two forth as man and wife, then make all the misty vapor gather. If not, then make all the misty vapor disperse." At this, the misty vapor immediately gathered. When the sister became intimate with her brother, they plaited some grass to make a fan to screen their faces. Even today, when a man takes a wife, they hold a fan, which is a symbol of what happened long ago.[9]

In Yuchuan Ziji (玉川子集 c. 618 – 907 AD), Chapter 3 ("與馬異結交詩" 也稱 "女媧本是伏羲婦"), author Lu Tong describes Nüwa as the wife of Fuxi.

In Siku Quanshu, Sima Zhen (679–732) provides commentary on the prologue chapter to Sima Qian's Shiji, "Supplemental to the Historic Record: History of the Three August Ones", wherein it is found that the Three August Ones are Nüwa, Fuxi, and Shennong; Fuxi and Nüwa have the same last name, Feng (Chinese: 風; Hmong: Faj).[lower-alpha 3]

In the collection Four Great Books of Song (c. 960 – 1279 AD), compiled by Li Fang and others, Volume 78 of the book Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era contains a chapter "Customs by Yingshao of the Han Dynasty" in which it is stated that there were no men when the sky and the earth were separated. Thus Nüwa used yellow clay to make people. But the clay was not strong enough so she put ropes into the clay to make the bodies erect. It is also said that she prayed to gods to let her be the goddess of marital affairs. Variations of this story exist.

Appearance in Fengshen Yanyi

.jpg.webp)

Nüwa is featured within the famed Ming dynasty novel Fengshen Bang. As featured within this novel, Nüwa is very highly respected since the time of the Xia Dynasty for being the daughter of the Jade Emperor; Nüwa is also regularly called the "Snake Goddess". After the Shang Dynasty had been created, Nüwa created the five-colored stones to protect the dynasty with occasional seasonal rains and other enhancing qualities. Thus in time, Shang Rong asked King Zhou of Shang to pay her a visit as a sign of deep respect. After Zhou was completely overcome with lust at the very sight of the beautiful ancient goddess Nüwa (who had been sitting behind a light curtain), he wrote an erotic poem on a neighboring wall and took his leave. When Nüwa later returned to her temple after visiting the Yellow Emperor, she saw the foulness of Zhou's words. In her anger, she swore the Shang Dynasty would end in payment for his offense. In her rage, Nüwa personally ascended to the palace in an attempt to kill the king, but was suddenly struck back by two large beams of red light.

After Nüwa realized that King Zhou was already destined to rule the kingdom for twenty-six more years, Nüwa summoned her three subordinates—the Thousand-Year Vixen (later becoming Daji), the Jade Pipa, and the Nine-Headed Pheasant. With these words, Nüwa brought destined chaos to the Shang Dynasty, "The luck Cheng Tang won six hundred years ago is dimming. I speak to you of a new mandate of heaven which sets the destiny for all. You three are to enter King Zhou's palace, where you are to bewitch him. Whatever you do, do not harm anyone else. If you do my bidding, and do it well, you will be permitted to reincarnate as human beings[10]." With these words, Nüwa was never heard of again, but was still a major indirect factor towards the Shang Dynasty's fall.

Creation of humanity

Nüwa created humanity due to her loneliness, which grew more intense over time. She molded yellow earth or, in other versions, yellow clay into the shape of people. These individuals later became the wealthy nobles of society, because they had been created by Nüwa's own hands. However, the majority of humanity was created when Nüwa dragged string across mud to mass-produce them, which she did because creating every person by hand was too time- and energy-consuming. This creation story gives an aetiological explanation for the social hierarchy in ancient China. The nobility believed that they were more important than the mass-produced majority of humanity, because Nüwa took time to create them, and they had been directly touched by her hand.[11] In another version of the creation of humanity, Nüwa and Fuxi were survivors of a great flood. By the command of the God of the heaven, they were married and Nüwa had a child which was a ball of meat. This ball of meat was cut into small pieces, and the pieces were scattered across the world, which then became humans.[12]

Arranger of marriages

Nüwa was born three months after her brother, Fuxi, to whom she later took as her husband; this marriage is the reason why Nüwa is credited with inventing the idea of marriage.[11]

Nüwa and Fuxi

Before the two of them got married, they lived on mount K'un-lun. A prayer was made after the two became guilty of falling for each other. The prayer is as follows,

"Oh Heaven, if Thou wouldst send us forth as man and wife, then make all the misty vapor gather. If not, then make all the misty vapor disperse."[11]

Misty vapor then gathered after the prayer signifying the two could marry. When intimate, the two made a fan out of grass to screen their faces which is why during modern day marriages, the couple hold a fan together. By connecting, the two were representative of Yin and Yang; Fuxi being connected to Yang and masculinity along Nüwa being connected to Yin and femininity. This is further defined with Fuxi receiving a carpenter's square which symbolizes his identification with the physical world because a carpenter's square is associated with straight lines and squares leading to a more straightforward mindset. Meanwhile, Nüwa was given a compass to symbolize her identification with the heavens because a compass is associated with curves and circles leading to a more abstract mindset. With the two being married, it symbolized the union between heaven and Earth.[11] Other versions have Nüwa invent the compass rather than receive it as a gift.[13]

In pop culture/reception

Music

Nüwa invented multiple musical instruments: The Shenghuang, Saengwhang, and Hulusi gourd flute (all of these instruments are various reed pipes). Nüwa created the Shenghuang around the idea of reproduction; the Shenghuang is used in marriages and reproduction rites.[14] With regards to the Saengwhang, Nüwa created this instrument to be in the shape of the god of music, Bonghwang.[15] Chinese musical theaters around the world have pictures of Nüwa decorating their interiors.[16]

Nüwa Mends the Heavens

Nüwa Mends the Heavens (Chinese: 女娲補天; Chinese: 女娲补天; pinyin: Nǚwā bǔtiān) is a well-known theme in Chinese culture. The courage and wisdom of Nüwa inspired the ancient Chinese to control nature's elements and has become a favorite subject of Chinese poets, painters, and sculptors,[17] along with so many poetry and arts like novels, films, paintings, and sculptures; e.g. the sculptures that decorate Nanshan[18] and Ya'an.[19]

Nuwa the human creator

The Huainanzi tells an ancient story about how the four pillars that support the sky crumbled inexplicably. Other sources have tried to explain the cause, i.e. the battle between Gong Gong and Zhuanxu or Zhu Rong. Unable to accept his defeat, Gong Gong deliberately banged his head onto Mount Buzhou (不周山) which was one of the four pillars. Half of the sky fell which created a gaping hole and the earth itself was cracked; the earth's axis mundi was tilted into the southeast while the sky rose into the northwest. This is said to be the reason why the western region of China is higher than the eastern and that most of its rivers flow towards the southeast. This same explanation is applied to the sun, moon, and stars which moved into the northwest. A wildfire burnt the forests and led the wild animals to run amok and attack the innocent peoples, while the water which was coming out from the earth's crack didn't seem to be slowing down.[20]

Nüwa pitied the humans she had made and attempted to repair the sky. She gathered five colored-stones (red, yellow, blue, black, and white) from the riverbed, melted them and used them to patch up the sky: since then the sky (clouds) have been colorful. She then killed a giant turtle (or tortoise), some version named the tortoise as Ao, cut off the four legs of the creature to use as new pillars to support the sky. But Nüwa didn't do it perfectly because the unequal length of the legs made the sky tilt. After the job was done, drove away the wild animals, extinguished the fire, and controlled the flood with a huge amount of ashes from the burning reeds. The world became as peaceful as it was before.[20][21]

Empress Nuwa

Many Chinese know well their Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, i.e. the early leaders of humanity as well as culture heroes according to the Northern Chinese belief. But the lists vary and depend on the sources used.[22] One version includes Nüwa as one of the Three Sovereigns, who reigned after Fuxi and before Shennong.[23]

In her matriarchal reign, she battled against a neighboring tribal chief, defeated him, and took him to the peak of a mountain. Defeated by a woman, the chief felt ashamed to be alive and banged his head on the heavenly bamboo to kill himself and for revenge. His act tore a hole in the sky and made a flood hit the whole world. The flood killed all people except Nüwa and her army which was protected by her divinity. After that, Nüwa patched the sky with five colored-stones until the flood receded.[24]

Culture

- Dream of the Red Chamber (1754) narrates how Nuwa gathered 36, 501 stones to patch the sky but left one unused. The unused stone plays an important role in the novel's storyline.[25]

- Goddess Nüwa statue named "Sky Patching" by Prof. Yuan Xikun was exhibited at Times Square, New York City, on 19 April 2012 to celebrate Earth Day (2012), symbolized the importance to protect ozone layer.[26] Previously, this 3.9 meters statue was exhibited on Beijing and now is placed on Vienna International Centre, Vienna since 21 November 2012.[27]

- "Goddess Nuwa patches up the sky" (2013) is an application for iPhone and iPad by Zero Studio.[28]

- The story of Nuwa patching the sky was being retold by "Carol Chen" on her book "Goddess Nuwa Patches Up the Sky" (2014) which was illustrated by "Meng Xianlong".[29]

- The movie Xīyóujìzhī Dànào Tiāngōng (西游記之大鬧天宮) ("Journey to the West – The Monkey created chaos in heaven") (2014) directed by "Soi Cheang Pou-soi" shows the battle between Jade Emperor (Chow Yun Fat) and Bull Demon King (Aaron Kwok). Nuwa (Zhang Zilin) sacrifices herself to repair heaven and make a heavenly gate to protect heaven from invading demons.[30]

Notes

- A different translation of the same text is also given in Lewis.[5]

- "In ancient times Gong Gong and Zhuan Xu fought, each seeking to become the thearch. Enraged, they crashed against Mount Buzhou; Heaven's pillars broke; the cords of Earth snapped. Heaven tilted in the northwest, and thus the sun and moon, stars and planets shifted in that direction. Earth became unfull in the southeast, and thus the watery floods and mounding soils subsided in that direction."[6]

- Sima Zhen's commentary is included with the later Siku Quanshu compiled by Ji Yun and Lu Xixiong.

References

- "Nügua". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Anne Birrell (1999), trans., The Classic of Mountains and Seas. Penguin Books.

- 媧皇. Handian. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Major & al. (2010), ch. 6.

- Lewis (2006), p. 111.

- Major & al. (2010), ch. 3.

- Major & al. (2010), ch. 6 n.

- 大荒西經. 山海經 [Shan Hai Jing] (in Chinese).

- Translation in Birrell 1993, 35.

- Allan, Sarah; Allan, Sarah (1991). The shape of the turtle: myth, art, and cosmos in early China. SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0460-7.

- Thury, Eva M. (2017). Introduction to mythology : contemporary approaches to classical and world myths. ISBN 9780190262983. OCLC 946109909.

- Lianfe, Yang (1993). "Water in Traditional Chinese Culture". The Journal of Popular Culture. 27 (2): 51–56. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1993.00051.x. ISSN 0022-3840.

- Roberts, David Lindsay; Leung, Allen Yuk Lun; Lins, Abigail Fregni (2012), "From the Slate to the Web: Technology in the Mathematics Curriculum", Third International Handbook of Mathematics Education, Springer New York, pp. 525–547, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4684-2_17, ISBN 9781461446835

- 建 李 (March 2004). 女娲作笙簧: 神话的文化解读. Journal of Nantong Teachers College (Social Sciences Edition). 20: 106–109 – via China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House.

- 조석연 (2014). 조선시대 생황의 이중적 상징 의미에 대한 고찰. 국악원논문집 (Journal of the Korean Traditional Performing Arts Centre). 30: 211–232.

- "Creator Deities Fu Xi and Nu Wa".

- "NUWA REPAIRS THE HEAVENS (Nuwa Bu Tian)". Beijing: China on Your Mind. 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- dartman. "Goddess Nu Wa Patching the Sky". Panoramio. Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Zhitao Li. "Nuwa Patching the Sky". Dreamstime. Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- anonim (26 October 2009). "The Nuwa Sacrificial Ceremonies". Beijing: Confucius Institute Online. Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Skryrock. "Nüwa Repairs the Heavens". Chinese Geography. Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Hucker, Charles (1995). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780804723534.

- 劉煒/著. (2002) Chinese civilization in a new light. Commercial press publishing. ISBN 962-07-5314-3, p. 142.

- Mark Isaak (2 September 2002). "Flood Stories from Around the World". Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Lianhua Andy (25 September 2015). "Penciptaan Bumi & Manusia Menurut Chiness Mitologi (Pangu ,Nuwa & Fuxi)" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Unveiling Goddess Nüwa in NY Times Square and Beijing". United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 22 April 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Ozone statue unveiled in Vienna to mark Montreal Protocol anniversary". UNIDO. 22 November 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Goddess Nuwa patches up the sky". Zero Studio. 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- anonim (2014). "Goddess Nuwa Patches Up the Sky – the Chinese Library Series (Paperback)". AbeBooks Inc. Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Jedd Jong (4 February 2014). "The Monkey King". Retrieved 15 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Bibliography

- Birrell, Anne (1993), Chinese Mythology: An Introduction, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2006), The Flood Myths of Early China, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-6663-6.

- Major, John S.; et al., eds. (2010), The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14204-5.

Further reading

- Allan, Sarah (1991), The shape of the turtle: myth, art, and cosmos in early China, SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-0460-9

External links

Media related to Nuwa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nuwa at Wikimedia Commons