Little Red Rooster

"Little Red Rooster" (or "The Red Rooster" as it was first titled) is a blues standard credited to arranger and songwriter Willie Dixon. The song was first recorded in 1961 by American blues musician Howlin' Wolf in the Chicago blues style. His vocal and slide guitar playing are key elements of the song. It is rooted in the Delta blues tradition and the theme is derived from folklore. Musical antecedents to "Little Red Rooster" appear in earlier songs by blues artists Charlie Patton and Memphis Minnie.

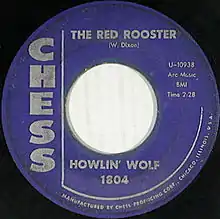

| "The Red Rooster" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Howlin' Wolf | |

| B-side | "Shake for Me" |

| Released | October 1961 |

| Recorded | Chicago, June 1961 |

| Genre | Chicago blues |

| Length | 2:25 |

| Label | Chess |

| Songwriter(s) | Willie Dixon |

| Producer(s) | |

A variety of musicians have interpreted and recorded "Little Red Rooster". Some add new words and instrumentation to mimic the sounds of animals mentioned in the lyrics. American soul music singer Sam Cooke adapted the song using a more uptempo approach and it became a successful single on both the US rhythm and blues and pop record charts in 1963. Concurrently, Dixon and Howlin' Wolf toured the UK with the American Folk Blues Festival and helped popularize Chicago blues with local rock musicians overseas.

The Rolling Stones were among the first British rock groups to record modern electric blues songs. In 1964, they recorded "Little Red Rooster" with original member Brian Jones, a key player in the recording. Their rendition, which remains closer to the original arrangement than Cooke's, became a number one record in the UK and continues to be the only blues song to reach the top of the British chart. The Stones frequently performed it on television and in concert and released several live recordings of the song. "Little Red Rooster" continues to be performed and recorded, making it one of Willie Dixon's best-known compositions.

Background

Willie Dixon's "The Red Rooster"/"Little Red Rooster" uses elements from several earlier blues songs.[1] The theme reflects early twentieth century folk beliefs in the American South that a rooster contributes to peace in the barnyard.[2][3] The image of the rooster appears in several blues songs from the 1920s and 1930s, with two particular songs identified as precursors.[3] Influential Delta blues musician Charlie Patton's 1929 "Banty Rooster Blues" contains the verses "What you want with a rooster, he won't crow 'fore day" and "I know my dog anywhere I hear him bark", which are analogous to Dixon's "I have a little red rooster, too lazy to crow 'fore day" and "Oh the dogs begin to bark".[3] Some of the lyrics to Memphis Minnie's 1936 acoustic combo blues "If You See My Rooster (Please Run Him Home)" are also similar. For example, she sings "If you see my rooster, please run 'im on back home", while Dixon uses "If you see my little red rooster, please drive 'im home".[3] Additionally, similar melody lines are found in both songs.[3] For her recording, Memphis Minnie does a full-throated imitation of a rooster's crow.[4] Mimicking animal sounds later became a feature of several recordings of "Little Red Rooster".[5][6]

In the post-war era, Margie Day with the Griffin Brothers recorded a song in 1950 titled "Little Red Rooster" in an updated jump blues style. It is a boisterous, uptempo piece performed by a small combo group.[7] Day's lyrics include "Got a little red rooster, and man how he can crow ... He's a boss of the barnyard, any ol' place he goes"; Dixon's song uses the line "Keep everything in the barnyard, upset in every way".[8] The original Dot Records single lists the songwriters as "Griffin-Griffin".[9][lower-alpha 1] Day's song was a hit, reaching number five on Billboard's Best Selling Retail Rhythm & Blues Records chart in 1951.[11]

Howlin' Wolf song

Delta blues musician Charlie Patton influenced Howlin' Wolf's early musical development. Wolf later recorded adaptations of several Patton songs, including "Spoonful", "Smokestack Lightning", and "Saddle My Pony".[12] Relatives and early friends recall Howlin' Wolf playing a song similar to "The Red Rooster" in the 1930s.[13] Evelyn Sumlin, who was the wife of long-time Wolf guitarist Hubert Sumlin, felt that several of the songs that were later arranged by and credited to Willie Dixon had already been developed by Howlin' Wolf.[14][lower-alpha 2]

Howlin' Wolf recorded "The Red Rooster" in Chicago in June 1961.[16] The song is performed as a slow blues in the key of A. Although Dixon biographer Mitsutoshi Inaba notes it as a twelve-bar blues,[17] the changes in the first section vary due to extra beats. Lyrically, it follows the classic AAB blues pattern,[17] where two repeated lines are followed by a second. The opening verse echoes Charlie Patton's second verse:[18]

I have a little red rooster, too lazy to crow 'fore day (2×)

Keep everything in the barnyard, upset in every way

As with many blues songs, Dixon's lyrics are ambiguous and may be seen on several levels.[19] Interpretations of his verses range from the "most overtly phallic song since Blind Lemon Jefferson's [1927] 'Black Snake Moan'"[20] to an innocuous farm ditty.[2] Although Dixon described it in the latter terms, he added, "I wrote it as a barnyard song really, and some people even take it that way!"[21] The lyrics are delivered in Howlin' Wolf's distinctive vocal style; music writer Bill Janovitz describes it as displaying a "master singer's attention to phrasing and note choice, milking out maximum emotion and nuance from the melody".[22]

A key element of the song is the distinctive slide guitar, played by Howlin' Wolf, with backing by long-time accompanist Hubert Sumlin on electric guitar.[22] It is one of only two of the many songs recorded by Howlin' Wolf in the early 1960s which include his guitar playing.[23] Described as "slinky" by Janovitz[22] and "sly" by music historian Ted Gioia,[24] it weaves in and out of the vocal lines and is the stylistic foundation of the song.[22] The other musicians include Johnny Jones on piano, Willie Dixon on double bass, Sam Lay on drums,[16] and possibly Jimmy Rogers on guitar.[22]

"The Red Rooster", backed with "Shake for Me", which was also recorded during the same session, was issued by Chess Records in October 1961.[25] Neither song, nor his other songs from the period now considered to be among his best known, entered the record charts.[26][27] Both were included on his acclaimed 1962 album Howlin' Wolf, often called the Rockin' Chair album. "The Red Rooster" also appears on many Howlin' Wolf compilations, including Howlin' Wolf: The Chess Box and Howlin' Wolf: His Best – The Chess 50th Anniversary Collection.[22]

Later, Chess arranged for Howlin' Wolf to record "The Red Rooster" and some other songs with Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts for the 1971 album The London Howlin' Wolf Sessions. At the beginning of the recording, Howlin' Wolf can be heard attempting to explain the timing of the song, because as Wyman later explained, "we were kind of playing it backwards".[28] Finally, Clapton (joined in by the others) encourages him to play it on guitar so "I can follow you if I can see what you're doing".[29] Despite their efforts to get it right, according to Wyman, "the Chess people ended up using the old 'backwards' take anyway".[28]

Sam Cooke rendition

On February 23, 1963, American soul singer Sam Cooke recorded his interpretation of Willie Dixon's song, calling it "Little Red Rooster".[30] The song was first proposed for Cooke's brother, L.C., who was recording some new material at the time. However, L.C. felt the song was not suitable for him. "I said, 'I'm not a blues singer.' So Sam said, 'Well, I'm gonna do it then,'" L.C. recalled.[31] Sam Cooke chose to forgo Howlin' Wolf's gutbucket approach and came up with an arrangement that music writer Charles Keil describes as "somewhat more relaxed and respectable".[32] Dixon's lyrics are delivered in Cooke's articulate vocal style, but with an additional verse:[33][lower-alpha 3]

I tell you that he keeps all the hens, fighting among themselves

Keeps all the hens, fighting among themselves

He don't want no hen in the barnyard, layin' eggs for nobody else

Cooke's musical arrangement follows a typical twelve-bar blues structure and is performed at a faster tempo than Howlin' Wolf's. It has been notated as a moderate blues (92 beats per minute) in 12/8 time in the key of A.[34] The recording took place in Los Angeles with a small group of session musicians. A young Billy Preston uses "playful organ vocalizing" or organ lines to imitate the sounds of a rooster crowing and, following the lyrics, dogs barking and hounds howling.[5] Also backing Cooke are Ray Johnson on piano and Hal Blaine on drums[35] (Barney Kessel has also been mentioned as the guitarist).[22] The song was a hit, reaching number seven on Billboard's Hot R&B singles chart. It was also a crossover hit and appeared at number eleven on the Billboard Hot 100 pop chart.[36] "Little Red Rooster" is included on Cooke's 1963 album Night Beat, which reached number 62 on the Billboard 200 album chart.[37] It also appears on several Cooke compilation albums, including Portrait of a Legend: 1951–1964, which was released in 2003.[38]

Rolling Stones version

| "Little Red Rooster" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Italian single picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Rolling Stones | ||||

| B-side | "Off the Hook" | |||

| Released |

| |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Blues | |||

| Length | 3:05 | |||

| Label | Decca | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Willie Dixon | |||

| Producer(s) | Andrew Loog Oldham | |||

| Rolling Stones UK singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Background

Chess Records Chicago artists, including Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters, influenced the Rolling Stones, with the band taking their name from a Muddy Waters tune and playing from a repertoire of blues songs at the beginning of their career. In 1962, before they had recorded as a group, Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, and Keith Richards, attended the first American Folk Blues Festival, whose performers included Howlin' Wolf.[20] Willie Dixon, another Festival player, later recalled "When the Rolling Stones came to Chess studios, they had already met me and doing my songs, especially 'Little Red Rooster'".[39] When Dixon and Howlin' Wolf were in London, they met several local rock musicians. Early Stones manager Giorgio Gomelsky described such a meeting:

There was Howlin' Wolf, Sonny Boy [Williamson II] and Willie Dixon, the three of them sitting on this sofa ... Willie was just singing and tapping on the back of the chair and Sonny Boy would play the harmonica and they would do new songs. To a degree, that's why people know those songs and recorded them later. I remember '300 Pounds of Joy', 'Little Red Rooster', 'You Shook Me' were all songs Willie passed on at that time ... Jimmy Page came often, the Yardbirds, [and] Brian Jones.[39]

Dixon added, "I left lots of tapes when I was over there [in London ... I told] them anybody who wanted to could go and make a blues song. That's how the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds got their songs".[39] Stones biographer Sean Egan noted, "In many ways, this is Brian Jones' record. [He was] always the biggest blues purist in the band".[1]

Although they had already recorded several Chess songs, according to Bill Wyman, "Little Red Rooster" was "a slow, intense blues song ... [that producer Andrew Loog Oldham argued was] totally uncommercial and wrong for our new-found fame ... the tempo made the track virtually undanceable".[40] Mick Jagger commented:

The reason we recorded 'Little Red Rooster' isn't because we want to bring blues to the masses. We've been going on and on about blues, so we thought it was about time we stopped talking and did something about it. We liked that particular song, so we released it. We're not on the blues kick as far as recording goes. The next record will be entirely different, just as all the others have been.[41]

Composition and recording

Although Wyman noted some early criticism of their rendition,[41] Janovitz described it as "a fairly faithful version [of the original]".[22] It is performed as a moderately slow (74 bpm) blues in the key of G.[42] Although AllMusic reviewer Matthew Greenwald describes their arrangement as having a straight I-IV-V twelve-bar blues progression,[43] they sometimes vary the changes, but not in the same manner as Howlin' Wolf. Jagger uses the lyrics from the original (omitting Cooke's extra verse), but makes one important change—instead of "I got a little red rooster", he sings "I am the little red rooster", although the later verse reverts to "If you see my little red rooster".[44] Instrumentally, Bill Wyman generally follows Dixon's bass lines.[22] Charlie Watts later admitted that his drum part was inspired by Sam Cooke's version,[45] which was played by Hal Blaine. Keith Richards adds a rhythm guitar part; according to Egan, "the juxtaposition of acoustic guitar and electric slide all make for something richer and warmer than any blues they had ever attempted before".[1]

However, it is Jones' contributions that are usually singled out. Egan writes "it is his [Jones'] playing that makes the record via both the cawing bottleneck that is its most prominent feature and his closing harmonica".[1][lower-alpha 4] Biographer Stephen Davis adds, "It was his [Jones'] masterpiece, his inspired guitar howling like a hound, barking like a dog, crowing like a rooster"[6] (similar to Billy Preston's "playful organ vocalizing"). Wyman wrote "I believe 'Rooster' provided Brian Jones with one of his finest hours.[41]

Two different dates and recording locations are given. Wyman recalled that the song was recorded September 2, 1964, at Regent Sound in London,[46] while the session information for the 1989 Rolling Stones box set Singles Collection: The London Years lists "November 1964 Chess Studios, Chicago".[47] Biographer Massimo Bonanno commented, "The boys entered the Regent Sound Studios on September 2nd [1964] to resume work on ... 'Little Red Rooster' ... [and later on November 8, 1964, at Chess] some unverified sources [indicate] the boys also put the final touches to their next British single 'Little Red Rooster'".[48] According to Davis, Jones was left to later record overdubs after the track was recorded without him.[49]

Charts and releases

"Little Red Rooster" was released on Friday, November 13, 1964,[41] and reached number one on the UK Singles Chart on December 5, 1964, where it stayed for one week.[50] It remains to this day the only time a blues song has ever topped the British pop charts.[41] According to AllMusic writer Matthew Greenwald, "Little Red Rooster" was Brian Jones' favorite Stones single.[43] Wyman noted that it "realized a cherished ambition [of Jones] to put blues music at the top of the charts, and meant his guilt of having 'sold out' completely to pop fame was diminished".[41] It was the band's last cover song to be released as a single during the 1960s.[lower-alpha 5]

In 1964 and 1965, the Rolling Stones performed "Little Red Rooster" several times on television, including the British programs Ready Steady Go! (November 20, 1964) and Thank Your Lucky Stars (December 5, 1964); and the American The Ed Sullivan Show (May 2, 1965), Shindig! (May 20, 1965), and Shivaree (May 1965).[52][53][20] On Shindig!, Jagger and Jones introduced Howlin' Wolf as the first one to record "Little Red Rooster" and as one of their first influences.[54] Although often reported that the Stones would only agreed to appear if Howlin' Wolf (or Muddy Waters) also performed,[55][56] Keith Richards later explained that the show's producer, Jack Good, was in on the idea to present an original blues artist on prime time network television.[45] During the group's concerts in 1965, Charlie Watts, who did not normally address the audiences, was often brought from behind the drum kit to the front of the stage to introduce "Little Red Rooster" from Jagger's microphone.[57] Wyman recalled particularly enthusiastic responses to the song in Sydney (at the Agricultural Hall in January 1965), Paris (Olympia in April 1965), and Long Beach, California (Long Beach Auditorium on May 16, 1965).[58]

"Little Red Rooster" is included on their third American album, The Rolling Stones, Now!, released in February 1965.[43] It also appears on several Rolling Stones compilation albums, including the UK version of Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass), Singles Collection: The London Years, Rolled Gold: The Very Best of the Rolling Stones, and GRRR!. Live versions appear on Love You Live and Flashpoint (with Eric Clapton, who contributed to Howlin' Wolf's 1971 remake, on slide guitar).[43]

No US single release

Bill Wyman later wrote in his book Stone Alone that "on December 18, 1964, news came from America that 'Little Red Rooster' was banned from record release because of its 'sexual connotations'".[59] This has been repeated and embellished to include that it had been banned by or from American radio stations; however, Sam Cooke's version with nearly the same lyrics had been a Top 40 crossover pop hit one year earlier. Additionally, the Rolling Stones' "Little Red Rooster" was included on Los Angeles radio station KRLA's (at the time the number-one Top 40 radio station in the second largest market in the US) playlist from December 9, 1964[60] to February 5, 1965.[61] Radio personality Bob Eubanks wrote in his weekly Record Review column for January 1, 1965, "'Little Red Rooster', by the Stones, is still KRLA's exclusive ... Don't fret, though, it may still be released in this country".[62]

"Mona (I Need You Baby)" from the Rolling Stones' first UK album was also being aired and considered for their next single,[63] but with "Time Is on My Side", "Heart of Stone", and "The Last Time" on the US charts during this same period, neither "Little Red Rooster" or "Mona" were released as singles. However, they were included on Rolling Stones, Now! (by contrast, only "Little Red Rooster" and "The Last Time" were released as singles in the UK during this period). Although it appeared at the top of the British chart for one week, Jagger later commented, "I still dig 'Little Red Rooster', but it didn't sell".[1] Egan believes that actual sales of the record may have fallen short of previous Stones' singles.[1]

Charts

| Chart (1964–65) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Flanders)[64] | 20 |

| Germany (Official German Charts)[65] | 14 |

| Ireland (IRMA)[66] | 4 |

| Netherlands (Single Top 100)[67] | 4 |

| Norway (VG-lista)[68] | 6 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[69] | 1 |

Recognition and influence

Howlin' Wolf's original "The Red Rooster" is included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's list of the "500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll".[70] As well as being a blues standard,[71] Janovitz calls "Little Red Rooster" a "classic song [that] has been recorded countless times, a warhorse for most late-'60s and 1970s classic rock acts".[22] Dixon and Snowden have noted cover versions by Luther Allison, Eddie C. Campbell, the Doors (with John Sebastian), Jose Feliciano, Grateful Dead,[72] Ronnie Hawkins, Z.Z. Hill, Hubert Sumlin, and Big Mama Thornton.[73]

Notes

Footnotes

- The Griffin Brothers are identified as Jimmy and Ernest "Buddy"; BMI lists the songwriters as Edward E. Griffin and James Griffin.[10] Margie Day has claimed that it was written by Kay Griffin with help from Day herself.

- Willie Dixon received a writer's credit for "Spoonful", while Howlin' Wolf (a.k.a. Chester Burnett) is listed as the composer for "Smokestack Lightning" and "Saddle My Pony".[15]

- Cooke's song has been described as "a humorous story about human sexuality".Dollars & Sense magazine, Volumes 1–6, 1995.

- Mick Jagger sometimes receives credit for the harmonica part[43] and would mime to the instrument on television appearances.[1]

- Subsequent singles released in the 1960s were composed by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, except one song credited to Bill Wyman, one cowritten by Andrew Loog Oldham, and two group compositions using the pseudonym "Nanker Phelge".[51]

Citations

- Egan 2013, eBook.

- Tomko 2005, p. 822.

- Inaba 2011, p. 221.

- Carroll 2005, p. 93.

- Bush, John. "Sam Cooke: Night Beat – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- Davis 2001, p. 115.

- Billboard 1950, p. 25.

- Hal Leonard 1995, p. 117.

- Little Red Rooster (Single label). Margie Day with Griffin Brothers Orchestra. Dot Records. 1950. OCLC 42851699. 1019-A.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Little Red Rooster (Legal Title) – BMI Work #882665". BMI. Archived from the original on February 17, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- Whitburn 1988, p. 613.

- Segrest & Hoffman 2004, p. 19.

- Segrest & Hoffman 2004, p. 180.

- Segrest & Hoffman 2004, p. 181.

- Fancourt, Morris & Shurman 1991, pp. 28–29.

- Fancourt, Morris & Shurman 1991, p. 29.

- Inaba 2011, p. 220.

- Howlin' Wolf (1961). The Red Rooster (Song recording). Chess Records. Event occurs at 0:12. 1804.

- Inaba 2011, p. ix..

- Norman 2012, eBook.

- Trager 1997, p. 247–248.

- Janovitz, Bill. "Howlin' Wolf: 'The Red Rooster' – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- Inaba 2011, p. 212.

- Gioia 2008, p. 299.

- Billboard 1961, p. 42.

- O'Neal, Jim (1980). "1980 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees: Howlin' Wolf". The Blues Foundation. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitburn 1988, p. 198.

- Fornatale 2013, p. 138.

- Clapton, Eric (1971). The Red Rooster (London Sessions w/false start and dialog) (Song recording). Chess Records. Event occurs at 0:44. CHD3-9332.

- Sam Cooke: Greatest Hits (Album notes). Sam Cooke. RCA Records. 1998. p. 7. 07863 67605-2.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Guralnick 2005, eBook.

- Keil 1992, p. 47.

- Sam Cooke (1963). Little Red Rooster (Song recording). RCA Victor Records. Event occurs at 1:12. 47-8247.

- "Little Red Rooster by Sam Cooke". MusicNotes.com. Alfred Publishing. November 3, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Gulla 2007, p. 123.

- Whitburn 1988, p. 101.

- "Sam Cooke: Chart History – Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Sam Cooke: 'Little Red Rooster' — Appears On". AllMusic. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- Dixon & Snowden 1989, pp. 134–135.

- Wyman 1991, pp. 307, 337.

- Wyman 1991, p. 337.

- "Little Red Rooster by the Rolling Stones". MusicNotes.com. Alfred Publishing. November 24, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Greenwald, Matthew. "The Rolling Stones: 'Little Red Rooster' – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- Eder 1989, p. 19.

- The Rolling Stones 2003, p. 91.

- Wyman 1991, p. 307.

- Eder 1989, p. 70.

- Bonanno 2013, eBook.

- Davis 2001, p. 106.

- "Rolling Stones – Singles". Official Charts. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- Eder 1989, pp. 16–59.

- Davis 2001, p. 116.

- Wyman 1991, pp. 341, 376, 384–385.

- Good, Jack (Producer) (May 20, 1965). Shindig! interview with Mick Jagger and Brian Jones (Television episode). Hollywood, California: ABC. Event occurs at 0:46.

- Segrest & Hoffman 2004, p. 222.

- Koda 1996, p. 123.

- Wyman 1991, pp. 353, 361, 382–383.

- Wyman 1991, pp. 353, 371, 382–383.

- Wyman 1991, p. 344.

- "Top Ten Up and Comers". KRLA Beat. December 9, 1964. p. 1.

- "Top Ten Up and Comers". KRLA Beat. February 5, 1965. p. 1.

- Eubanks 1965a, p. 4.

- Eubanks 1965b, p. 3.

- "Ultratop.be – The Rolling Stones – Little Red Rooster" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – The Rolling Stones – Little Red Rooster". GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Little Red Rooster". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – The Rolling Stones – Little Red Rooster" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – The Rolling Stones – Little Red Rooster". VG-lista. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "Rolling Stones: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- "500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 1995. Archived from the original on September 9, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- Herzhaft 1992, p. 467.

- Trager 1997, p. 247.

- Dixon & Snowden 1989, p. 248.

References

- Billboard (October 16, 1961). "Reviews of New Singles". Billboard. Vol. 73 no. 41. p. 42. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Billboard (December 23, 1950). "Margie Day – Record Review". Billboard. Vol. 62 no. 51. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Bonanno, Massimo (2013). The Rolling Stones: The First 50 Years. LA CASE Books. ISBN 978-8897526889.

- Carroll, Jeffrey (2005). When Your Way Gets Dark: A Rhetoric of the Blues. Parlor Press. ISBN 978-1932559385.

- Davis, Stephen (2001). Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40 Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. New York City: Doubleday Books. ISBN 978-0767909563.

- Dixon, Willie; Snowden, Don (1989). I Am the Blues. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80415-8.

- Eder, Bruce (1989). Singles Collection: The London Years (Box set booklet). The Rolling Stones. New York City: ABKCO Records. 1218-2.

- Egan, Sean (2006). The Rough Guide to the Rolling Stones. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-719-9.

- Egan, Sean (2013). The Mammoth Book of the Rolling Stones. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. ISBN 978-0762448142.

- Eubanks, Bob (January 1, 1965a). "Record Review". KRLA Beat.

- Eubanks, Bob (February 22, 1965b). "Record Review". KRLA Beat.

- Fancourt, Les; Morris, Chris; Shurman, Dick (1991). Howlin' Wolf: The Chess Box (Box set booklet). Howlin' Wolf. Universal City, California: MCA Records/Chess Records. CHD3-9332.

- Fornatale, Peter (2013). 50 Licks: Myths and Stories from Half a Century of the Rolling Stones. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1608199211.

- Gioia, Ted (2008). Delta Blues (Norton Paperback 2009 ed.). New York City: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-33750-1.

- Gulla, Bob (2007). Icons of R&B and Soul: An Encyclopedia of the Artists Who Revolutionized Rhythm. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313340451.

- Guralnick, Peter (2005). Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke. New York City: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316377942.

- Hal Leonard (1995). "Little Red Rooster". The Blues. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-79355-259-1.

- Herzhaft, Gerard (1992). "Red Rooster". Encyclopedia of the Blues. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-252-8.

- Inaba, Mitsutoshi (2011). Willie Dixon: Preacher of the Blues. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810869936.

- Keil, Charles (1992). Urban Blues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226429601.

- Koda, Cub (1996). "Howlin' Wolf". In Erlewine, Michael (ed.). All Music Guide to the Blues. San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-424-3.

- Norman, Philip (2012). Mick Jagger. New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0385669061.

- Palmer, Robert (1982). Deep Blues. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14006-223-8.

- The Rolling Stones (2003). According to the Rolling Stones. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0811840606.

- Segrest, James; Hoffman, Mark (2004). Moanin' at Midnight: The Life and Times of Howlin' Wolf. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-375-42246-3.

- Trager, Oliver (1997). The American Book of the Dead. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0684814025.

- Tomko, Gene (2006). "The Red Rooster". In Komara, Edward (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92699-7.

- Wald, Elijah (2004). Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (1st. ed.). New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060524272.

- Whitburn, Joel (1988). Top R&B Singles 1942–1988. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research. ISBN 0-89820-068-7.

- Wyman, Bill (1991). Stone Alone: The Story of a Rock 'n' Roll Band. New York City: Penguin Group.