Loch Vennachar

Loch Vennachar was a three-masted iron sailing ship (clipper) that operated between Great Britain and Australia between the late 19th century and 1905. The name was drawn from Loch Venachar, a lake which lies to the south-west of the burgh of Callander, in the Stirling region of Scotland. It is understood to mean "most beautiful lady" in Scottish Gaelic.[1]

_-_SLV_H99.220-6.jpg.webp) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Loch Vennachar |

| Owner: | Loch Line |

| Builder: | Thomson's on the Clyde |

| Launched: | August 1875 |

| In service: | 1875 |

| Out of service: | September 1905 |

| Fate: | Wrecked, near West Bay, SA, September 1905 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Clipper |

| Tonnage: | 1,485 tons |

| Length: | 250 ft 1 in (76.23 m) |

| Beam: | 38 ft 3 in (11.66 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 22 ft 4 in (6.81 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sail |

| Sail plan: | Clipper |

.jpg.webp)

In September 1905, she sank without trace and with all hands, leaving a spray of wreckage scattered along the south coast of Kangaroo Island. In 1976, her extensively damaged remains were discovered in an average depth of 12 metres (40 ft) of water near West Bay, Kangaroo Island in South Australia (SA) by the Society for Underwater Historical Research (SUHR).[2][3][4]

History and description

Loch Vennachar was built in 1875 by Thomson's on the Clyde for the Glasgow Shipping Company. She was one of a fleet of iron wool clippers of the well-known Loch Line.[5] Her registered tonnage and dimensions were: 1,552 tons gross, 1,485 tons net; length, 250 feet 1 inch; breadth, 38 feet 3 inches; depth of hold, 22 feet 4 inches. Her usual cargo was usually about 5,500 bales of wool. She was first rigged with fidded royal masts, but this proved to interfere with her stability as there was too much weight aloft. She was then given topgallant and royal masts in one with crossed royal yards over double-topgallants. Loch Vennachar was always in the wool trade to Adelaide and Melbourne, but when an out wool clipper, she also carried passengers[6] and other cargo.[7]

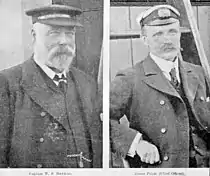

On her maiden voyage, she was commanded by Captain Francis Wagstaff, leaving Inishtrahull on 6 September 1875. In early 1876, Wagstaff was replaced by Captain William Robertson, who died in 1878 after only making two voyages on the vessel. The command was then given to her first officer, James S. Ozanne, but in 1884, Captain Ozanne handed over command to Captain William H. Bennett. Following Bennett's retirement in 1904,[8] Captain William S. Hawkins took command until her final voyage in 1905.[9]

Loch Vennachar was considered an unlucky ship narrowly surviving a cyclone in the Indian Ocean in June 1892.[10] Around 8 pm on 3 June, the barometer began to fall ominously and the sail was promptly shortened. At approximately 5.00 am as darkness lifted it showed terrific head seas that swept down upon the vessel, lashed by the North-East gale. Two large waves approached the ship. Loch Vennachar rode the first wave and sank into the trough at the other side. While in this position, the second wave came on and broke on deck with such force that it broke the foremast, mainmast and the mizzen topmast. Without her masts to steady her, the Loch Vennachar rolled dangerously in heavy seas. After 9 days, the weather eased and the crew were able to rig a spar forward and sail on the damaged mizzen. After 5 weeks of sailing, she arrived at Port Louis, Mauritius. Although her stay lasted 5 months while new spars were sent from England, repairs only took 10 days to complete.[7][9] Captain Bennett was awarded the Lloyd's Medal for his leadership and bravery at sea.[11]

Loch Vennachar suffered another serious accident on 12 November 1901, after a collision with the SS Cato, in the Thames Estuary. After arriving in the Thames, she anchored off the Mucking Light. Just before dawn, she was cut down and holed on the starboard bow by Cato, with one hand being seriously injured. She rapidly sank in 40 feet of water, but all hands, along with the parrot and cat, got clear safely.[12] She rested on the bottom of the Thames for a month before being raised and repaired at considerable cost,[13] and again put back into service in the Adelaide and Melbourne trade.[7][14][15][16]

Despite her unlucky reputation, she sailed between Great Britain and Australia for 30 years without further incident, until her final voyage.[17]

Final voyage

Under the command of Captain W.S. Hawkins, Loch Vennachar departed Glasgow in late June 1905 on a routine voyage to Adelaide. She was laden with general cargo including a consignment of 20,000 bricks. On 6 September 1905, Loch Vennachar was overtaken by SS Yongala about 160 miles west of the Neptune Islands and the captains exchanged "all's well" signals.[18] The Captain of the Yongala recorded that Loch Vennachar presented a pretty sight with her sails in full standing, she sped along with every apparent prospect of reaching her port safely.[19] It was the last known sighting of Loch Vennachar.

On 29 September, the ketch Annie Watt arrived in Adelaide and her captain reported picking up a reel of blue printing paper 18 miles North-West of Kangaroo Island. The paper was identified as part of Loch Vennachar's cargo.[11][20] Three weeks later, the sea began delivering scraps of her cargo to the jagged coast of Kangaroo Island which confirmed the disaster. The steamer Governor Musgrave was sent on two separate occasions to search for the wreck and any survivors. Weeks of searching by government and local fishing boats produced only flotsam and the body of a young seaman, who was never identified. He was buried in the sand hills of West Bay.[19] The search was eventually abandoned on 12 October.

At the time, it was incorrectly concluded that Loch Vennachar was wrecked on Young Rocks, a granite outcrop about 20 miles S.S.W. of Cape Gantheaume, trying to make the Backstairs Passage.[11]

Crew of the final voyage

The first list of persons likely to be on the ship at the time of her loss appeared in the news media in late September 1905. This list which contained 23 names of individuals who could be either crew or passengers was compiled from letters waiting for collection by the ship at the offices of George Wills & Co., the ship's agent in Adelaide.[21] A subsequent newspaper article advised that apprentices S.C. Brown and Robert Andrews had respectively transferred from Loch Vennachar to Loch Garry and Loch Torridon despite their names being included on the previously published list.[22] In late November 1905, the following list was published in a number of newspapers in Australia and in papers in both New Zealand and Scotland. This list which 'was received at Fremantle by the English mail' indicates that there were no passengers on the last voyage.[23]

|

|

|

In the above list, the abbreviations A.B. and O.S. refer respectively to Able seaman and Ordinary seaman.

The passing of Thomas Pearce received attention in the Australian press due to his father, Tom Pearce, being well known as one of the two survivors of the Loch Ard wrecking in 1878, and as his grandfather, Robert George Augustus Pearce,[24] was the captain of SS Gothenburg at the time of her loss in 1875.[25]

Aftermath

The loss of both Loch Vennachar and Loch Sloy convinced the Marine Board of South Australia to argue for the bringing forward of a plan that it recommended in 1902 to build a lighthouse at Cape du Couedic. Its view was that the loss of both ships could have been avoided if a lighthouse had been operating at Cape du Couedic. Construction commenced in 1907 and the light was officially lit on 27 June 1909.[26][27] The northern headland of West Bay was named Vennachar Point in the memory of the ship in 1908.[28]

Discovery of the wreck site

In February 1976, the SUHR conducted a search for the wreck along the west coast of Kangaroo Island. On 24 February, as conditions were unsuitable for underwater searching, a terrestrial search was conducted along the base of the 30 m (100 ft) high cliffs immediately north of West Bay. During this search, a brick with the letters ‘GLAS…OW’ on one of its faces was found. When conditions had improved on 26 February, SUHR divers Brian Marfleet, Doug Seton and Terry Smith joined by Kangaroo Island divers Chris and Robert Beckwith climbed down the cliff to enter the water at the location where the brick was found and later found the wreck site after 40 minutes of diving. An inspection of the wreck site revealed that all of the anchors were still in place on the ship suggesting that no attempt had been made to prevent the ship's collision with the cliff. After the discovery, the SUHR resolved to return to carry out a more comprehensive study of the wreck site.[4]

The Loch Vennachar Expedition

After lobbying by the SUHR, the SA Premier, Don Dunstan, announced on 11 December 1976 that the SUHR would be mounting an expedition in February 1977 to study the site and that the government will providing the following support – deployment of 10 police divers, special leave for government employees involved with the expedition and concessional fares on the government-owned ferry, MV Troubridge. Dunstan also announced the declaration of the area around the wreck site as a historic reserve under the SA Aboriginal and Historic Relics Preservation Act 1965.[29][30][31]

In February 1977, a party of 34 people arrived in 2 major movements at a camp site set up at West Bay for a stay of 2 weeks. Due to unsuitable diving conditions, the first week was spent diving the Fides shipwreck on the north coast of Kangaroo Island. The second week was spent at the Loch Vennachar wreck site where the SUHR was able to achieve the following outcomes – the location of the wreck site in respect to the land, a survey of the wreck's bow section including locating the major anchors, completion of a photographic site record and recovery of a selection of artefacts for conservation. The expedition was funded by member contributions along with the donation of services, goods and cash from 4 government agencies, 35 private businesses and numerous individuals.[32][33]

In 1979, as recommended in the Expedition's report, the opportunity to conserve one of the bower anchors was realised when grant funding became available. The SUHR collaborated with the SA Government and the Kangaroo Island Scuba Club to carry out the recovery. Assistance to the project was also provided by another 23 government agencies, private organisations and individuals. On 31 March 1980, an anchor shank was recovered from the wreck site followed by its stock on 1 April. Both parts were temporarily stored in the waters of West Bay for eventual collection and transfer by the fishing vessel, Lady Buick, to Kingscote respectively during April and May 1980. The shank and the stock were then respectively conveyed to Port Adelaide on MV Troubridge and on HMAS Banks. Conservation was carried out by Amdel in Adelaide. The conserved anchor was returned to Kangaroo Island where it was placed on display at the Flinders Chase Homestead in the Flinders Chase National Park, following a formal ceremony on 26 March 1982 attended by David Wotton, the SA Minister of Environment and Planning.[34][35][36]

Present day

The wreck site has been protected by the Commonwealth Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 since October 1980.[37] Its location is officially recorded as 35°52′48″S 136°31′12″E.[38] In 1980, the area protected as a historic reserve declared under the Aboriginal and Historic Relics Preservation Act 1965 was listed on the now-defunct Register of the National Estate.[39] The grave of the unidentified seaman can still be seen to this day at West Bay, however with a replica wooden cross as the original cross made from rigging spars from the wreckage was destroyed by vandals during the 1970s.[40][41][42] The bower anchor which was previously located at the Flinders Chase Homestead was moved to a site adjoining the visitors car park on the south side of West Bay prior to 2006.[43][44]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Loch Vennachar (1875). |

References

- De Quincey, T., & Groves, D. (2000). Articles from the Edinburgh Evening Post, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine and the Edinburgh Literary Gazette 1826 – 1829. London: Pickering and Chatto. OCLC: 174783948.

- Christopher, P., (1979), Some South Australian Shipwrecks, The Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia, ed. Nance, C., Historical Society of South Australia, North Adelaide, SA, No. 6, pp. 9.

- Council for Nautical Archaeology (1979). International journal of nautical archaeology and underwater exploration. London; Volume 8 Issue 2 Page 169-178, May 1979. ISSN 0305-7445. OCLC: 1037043.

- Reschke, W.; (1976), ‘Lady in a rocky coffin: the finding of Loch Vennachar,’ The Sunday Mail, 14 March 1976, pages 46 and 115.

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2003). Shipwrecks: Loch Vennachar. Retrieved online 22 March 2008.

- "In the year 1896 I left Glasgow in the Loch Vennachar for Melbourne, and had a wonderful run. Captain Bennett, who was a fine sailor, was in command, and taking the time from when we passed Ailsa Craig, in the Firth of Clyde, to Kangaroo Island, just outside Adelaide, we did the journey in 81 days. When we were "running our Easting down" in the Southern Ocean we on one occasion averaged 15 knots an hour for a period of over 24 hours. Her registered tonnage was 1,500, and the cabin accommodation and food were excellent." The Times, Saturday, 10 October 1931; pg. 8; Issue 45950; col B :Letter to the Editor: Mr. Stephen Scrope of 71, The Drive, Hove, 8 Oct.

- Loch Vennachar expedition report (1977), Society for Underwater Historical Research, Kent Town, South Australia. ISBN 0-9597500-1-0. OCLC: 27625714.

- "Sir, – With reference to the interesting letters which have appeared in your columns recently regarding the sailing ship Loch Vennachar and the master, that fine seaman Captain W. H. Bennett, no doubt your readers will be interested in the following extract from a letter which I have received to-day from his son, Mr. J. W. Bennett, who resides in London:- "My father was 85 years of age at his death, and left the Loch Vennachar in Melbourne in 1904,..." The Times, Tuesday, 20 October 1931; pg. 10; Issue 45958; col B: Letter to the Editor: G. B. Say, Chief Assistant Secretary. The Imperial Merchant Service Guild, Liverpool, 16 Oct..

- Ship Modelers Association (1997). The "Loch Vennachar". Retrieved online 22 March 2008.

- The New York Times (1911). Wrecks that mark the seven seas from Glasgow to Australia. Retrieved online 23 March 2008.

- Lubbock, Basil (1948). . Brown, Son & Ferguson, Glasgow. OCLC: 185535859.

- A report in The Times says the ship was anchored about 10 miles below Gravesend when at 4.15 am on Tuesday, 12 November 1901 she "was struck by the Cato abaft the starboard bow, a large hole being made." The captain (Captain Bennett) ordered the boats out and all 30 crew were taken off safely; but a seaman who was in the forecastle at the time of collision and sustained severe head injuries was in a critical condition. The Times, Wednesday, 13 Nov 1901; pg. 6; Issue 36611; col D

- "She was sunk when at anchor off Thameshaven by the steamer Cato in November 1901, and subsequently raised and repaired at a cost of £17,000." Mr Browning Dick of Lloyds, quoted in The Times, Wednesday, 14 October 1931; pg. 8; Issue 45953; col E

- The Ship Lists (2006).Glasgow Shipping Company Archived 1 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved online 21 March 2008.

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2003). Shipwrecks Audio Transcript > Vennachar Point. Retrieved online 22 March 2008.

- Art Fact (2008). Lot 625: Derek George Montague Gardner. Retrieved online 21 March 2008.

- Australian Government (2006). EMA Disasters Database: Kangaroo Island. Retrieved online 21 March 2008.

- "Loch Vennachar was passed on 6th 35 21 south, 133 east; she signalled all well; several gales since from north, changing west south cyclonic." The Times, Thursday, 28 September 1905; pg. 4; Issue 37824; col F:Shipping Disasters : quoting a telegram "received through Lloyds".

- Gleeson, Max (1987, p. 19). S.S. Yongala: dive to the past. Turton & Armstrong Publishers, Sydney. ISBN 0-908031-31-9. OCLC: 27579405

- "Messrs. Aitken, Lilburn, and Co., managers of the Loch Line, have received a telegram from their Adelaide agents confirming the discovery of wreckage, including paper and tinned fish with the same trade-marks as that shipped in the Loch Vennachar." The Times, Friday, 29 September 1905; pg. 4; Issue 37825; col F

- "Crew and Passengers' in 'Wreckage on Kangaroo Island; Cargo and figurehead washed ashore; Is it the Loch Vennachar?". The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA). 28 September 1905. p. 7. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- "Apprentices accounted for". The Register (Adelaide, SA). 3 October 1905. p. 8. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- "The Loss of the Loch Vennachar". The Register (Adelaide, SA). 25 November 1905. p. 6. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/60448681?searchTerm=r.g.a.%20pearce%20gothenburg&searchLimits=l-decade=187%7C%7C%7Cl-year=1875

- "'A much-wrecked family". The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA). 30 September 1905. p. 13. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Lighthouse, Cape Du Couedic Rd, Parndana, SA, Australia, , retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Lighthouse for Cape Couedie". The Register (Adelaide, SA). 12 May 1906. p. 6. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- "'New Coastal Names,' in General News'". The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA). 18 September 1908. p. 8. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- Marfleet, B. & Hale, A.; (1977), ‘Logistics of Loch Vennachar Expedition 1977.' page 2, in Loch Vennachar expedition report, (1977), Society for Underwater Historical Research, Kent Town, South Australia.

- Reschke, W., (1976), ‘High risks for divers,’ The Sunday Mail, 12 December 1976, page 5.

- Chatterton, B.A. (13 January 1977). "Aboriginal and Historic Relics Preservation Act, 1965: Area of Sea Bed near West Bay, Kangaroo Island—Historic Reserve Declared" (PDF). The South Australian Government Gazette. Government of South Australia. p. 46. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

An area of the bed of the sea near West Bay, Kangaroo Island seaward of the cliff top in a circle having as its centre a point longitude 136° 32' east, latitude 35° 53' 05" south and having a radius of 250 metres.

- Steward, G., (1977), ‘Loch Vennachar – Expedition Leaders Report’, pages 1 & 5, in Loch Vennachar expedition report, (1977), Society for Underwater Historical Research, Kent Town, South Australia.

- Marfleet, B. & Hale, A.; (1977), ‘Logistics of Loch Vennachar Expedition 1977,' page 2, in Loch Vennachar expedition report, (1977), Society for Underwater Historical Research, Kent Town, South Australia.

- Steward, G., (1977), ‘Loch Vennachar – Expedition Leaders Report,’ page 6, in Loch Vennachar expedition report, (1977), Society for Underwater Historical Research, Kent Town, South Australia.

- Jeffery, W., 1980, 'Raising the Loch Vennachar Anchor', Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology, Vol. 4, pp.6–7.

- Kentish, P. & Booth, B., 1983, Conservation of the Loch Vennachar anchor, Society for Underwater Historical Research, North Adelaide, pp. 5 to 8 and 15 to 18.

- 'Proclamation – Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 – South Australia – F2009B00096,' , retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "View Shipwreck – Loch Vennachar". Australian National Shipwreck Database. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Loch Vennachar Historic Reserve, South Coast Rd, Vennachar Point via Parndana, SA, Australia - listing on the now-defunct Register of the National Estate (Place ID 7455)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of the Environment. 11 August 1987. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Christopher, P.; (1979), Some South Australian Shipwrecks, The Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia, ed. Nance, C., Historical Society of South Australia, North Adelaide, SA, No. 6, pp. 9.

- 'Expedition Leaders Report,' page 4 in Loch Vennachar expedition report (1977), Society for Underwater Historical Research, Kent Town, South Australia.

- Smith, Andrea (2006), The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Kangaroo Island, South Australia: A Study of Kingscote and West Bay, unpublished thesis for the Honours Degree of the Bachelor of Archaeology, Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, South Australia, pages 54, Archived 6 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Smith, Andrea (2006), The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Kangaroo Island, South Australia: A Study of Kingscote and West Bay, unpublished thesis for the Honours Degree of the Bachelor of Archaeology, Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, South Australia, pages 54 & 55, Archived 6 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "Flinders Chase National Park, Kelly Hill Conservation Park, Ravine des Casoars Wilderness Protection Area and Cape Bouguer Wilderness Protection Area Management Plans" (PDF). Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs. 1999. p. 38. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

Further reading

- Chapman, Gifford D.; (2007), Kangaroo Island shipwrecks : an account of the ships and cutters wrecked around Kangaroo Island, Gifford Chapman, Kingscote, South Australia, (ISBN 9780646477794).

- Christopher, Peter; (2009), Australian Shipwrecks. A Pictorial History, Axiom, Stepney, South Australia (ISBN 9781864765885).

- McKinnon, R.; (1993), Shipwreck sites of Kangaroo Island, State Heritage Branch, Department of Environment and Land Management. Adelaide (ISBN 0730826929).

External links

- Shipwrecks and sea rescue: Shipwrecks, 1900–1907, SA Memory South Australia: past and present, for the future, retrieved 13 August 2012.

- 'Shipwrecks; Loch Vennachar,', retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Video of the wreck of the Loch Vennachar, Kangaroo Island, South Australia, May 2011, retrieved 25 June 2013

- A Model of the Iron Wool Clipper Loch Vennachar 1875 – 1905, retrieved 4 July 2013