RMS Tayleur

RMS Tayleur was a full-rigged iron clipper ship chartered by the White Star Line. She was large, fast and technically advanced. She ran aground off Lambay Island and sank on her maiden voyage in 1854. Of more than 650 aboard, only 280 survived.[1] She has been described as "the first Titanic".[2]

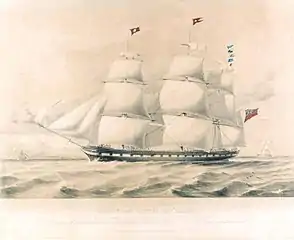

RMS Tayleur in full sail | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner: | Charles Moore & Company |

| Builder: | William Rennie, Liverpool |

| Launched: | 4 October 1853 |

| Fate: | Ran aground at Lambay Island on maiden voyage, 21 January 1854 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Clipper, iron hull |

| Length: | 230 ft (70 m ) |

| Beam: | 40 ft (12 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Complement: | 652 passengers and crew |

| Notes: | 3 decks |

History

Construction

Tayleur was designed by William Rennie of Liverpool and built at the Charles Tayleur foundry at Warrington for owners Charles Moore & Company of Mooresfort lattin, Co Tipperary. She was launched in Warrington on the River Mersey on 4 October 1853 - it had taken just six months to build her. She was 230 feet in length with a 40-foot beam and displaced 1,750 tons, while 4,000 tons of cargo could be carried in holds 28 feet deep below three decks. She was named after Charles Tayleur, founder of the Vulcan Engineering Works, Bank Quay, Warrington.

The new ship was chartered by White Star to serve the booming Australian trade routes, as transport to and from the colony was in high demand due to the discovery of gold there.

Disaster

Tayleur left Liverpool on 19 January 1854, on her maiden voyage, for Melbourne, Australia, with a complement of 652 passengers and crew. She was mastered by 29-year-old Captain John Noble. During the inquiry, it was determined that her crew of 71 had only 37 trained seamen amongst them, and of these, ten could not speak English. It was reported in newspaper accounts that many of the crew were seeking free passage to Australia. Most of the crew were able to survive.

Her compasses did not work properly because of the iron hull. The crew believed that they were sailing south through the Irish Sea, but were actually travelling west towards Ireland. On 21 January 1854, within 48 hours of sailing, Tayleur found herself in a fog and a storm, heading straight for the island of Lambay. The rudder was undersized for her tonnage, so that she was unable to tack around the island. The rigging was also faulty; the ropes had not been properly stretched, so that they became slack, making it nearly impossible to control the sails. Despite dropping both anchors as soon as rocks were sighted, she ran aground on the east coast of Lambay Island, about five miles from Dublin Bay.

Initially, attempts were made to lower the ship's lifeboats, but when the first one was smashed on the rocks, launching further boats was deemed unsafe. Tayleur was so close to land that the crew was able to collapse a mast onto the shore, and some people aboard were able to jump onto land by clambering along the collapsed mast. Some who reached shore had carried ropes from the ship, allowing others to pull themselves to safety on the ropes. Captain Noble waited on board Tayleur until the last minute, then jumped towards shore, being rescued by one of the passengers.

With the storm and high seas continuing, the ship was then washed into deeper water. She sank to the bottom with only the tops of her masts showing.

A surviving passenger alerted the coastguard station on the island. This passenger and four coast guards launched the coastguard galley. When they reached the wreck they found the last survivor, William Vivers, who had climbed to the tops of the rigging, and had spent 14 hours there. He was rescued by the coastguards. On 2 March 1854, George Finlay, the chief boatman, was awarded an RNLI silver medal for this rescue.[3]

Newspaper accounts blamed the crew for negligence, but the official Coroner's Inquest absolved Captain Noble and placed the blame on the ship's owners, accusing them of neglect for allowing the ship to depart without its compasses being properly adjusted. The Board of Trade, however, did fault the captain for not taking soundings, a standard practice when sailing in low visibility. The causes of the wreck were complex and included:

- Compass problems due to the placing of an iron river steamer on the deck after the compasses had been swung.

- Absence of a mast head compass placed at a distance from the iron hull.

- Northerly current in the Irish sea similar to that which drove the Great Britain northward.

- Slotting effect of the wind in the sails driving the ship sideways.

- Small untried crew to manage the sails.

- Large turning circle making ship unmaneuverable.

- The anchor chains broke when they were dropped in final efforts to save the ship.

- The captain had been injured in a serious fall and may have had head injuries.

- Lack of lifebelts - then uncommon and panic led to increased loss of life, those who kept their heads or could swim, escaped.

Tayleur has been compared with RMS Titanic. They shared similarities in their separate times. Both were RMS ships and White Star Liners (although these were different companies), and both went down on their maiden voyages. Inadequate or faulty equipment contributed to both disasters (faulty compasses and rigging for the Tayleur, and lack of binoculars and life boats for the Titanic).

Enquiries

There were four official enquiries: The inquest, held at Malahide; The Board of Trade Inquiry under Captain Walker; The Admiralty investigation was held by Mr Grantham, Inspector of Iron Ships; The Liverpool Maritime Board tried the fitness of Captain Noble to command. There are contradictions between these enquiries.

Estimates of the number of lives lost vary, as do the numbers on board. The latter are between 528 and 680, while the dead are supposed to be at least 297, and up to 380, depending on source. Out of over 100 women on board, only three survived, possibly because of the difficulty with the clothing of that era. The survivors were then faced with having to get up an almost sheer 80 foot (24m) cliff to get to shelter. When word of the disaster reached the Irish mainland, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company sent the steamer Prince to look for survivors. Recent research by Dr Edward J Bourke names 662 on board.[4]

A memorial to those killed in the wreck was unveiled at Portrane (53.493441 -6.108558) on 16 May 1999.[5]

Diving

The remains of the wreck were rediscovered in 1959 by members of the Irish Sub-Aqua Club.[6] Because the wreck is over 100 years old (166 as of 29 December 2019) a licence to dive the site must be obtained from the Office of Public Works.

The wreck lies at 17 metres depth some 30m off the southeast corner of Lambay Island in a small indentation at 53°28′54″N 06°01′12″W. Substantial wreckage includes the hull, side plates, a donkey engine and the lower mast. The woodwork was salvaged shortly after the wreck. Crockery from the cargo and several pieces of the wreck are on display at Newbridge House, Donabate.

References

- Guy, Stephen (2010). "Wreck of the Tayleur". National Museums Liverpool Blog.

- Starkey, H. F. (1999). Iron clipper "Tayleur": the White Star Line's "First Titanic". Avid Publications. ISBN 1902964004.

- "RNLI Gallantry Medals". Coastguards of Yesteryear. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Bourke, Edward J. (2003). Bound for Australia: The loss of the emigrant ship Tayleur at Lambay on the coast of Ireland. Dublin: Edward Bourke. ISBN 095230273X.

- Luxton, John (1999). "The Tayleur Memorial, Portrane". Irish Sea Shipping. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- Stone, Peter. "Shipwrecks on the UK - Australia Run". Encyclopedia of Australian Shipwrecks. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

The sinking of RMS Tayleur, the lost story of the Victorian Titanic, Gill Hoffs, Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2014, ISBN 178303047X.