Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the novel Treasure Island (1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson. The most colourful and complex character in the book, he continues to appear in popular culture. His missing leg and parrot, in particular, have greatly contributed to the image of the pirate in popular culture. His name is also commonly used as a slang term to describe an extra long glass vessel.

| John Silver | |

|---|---|

| Treasure Island character | |

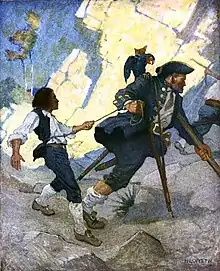

Long John Silver and Jim Hawkins in The Hostage, illustration by N. C. Wyeth, 1911 | |

| Created by | Robert Louis Stevenson |

| Voiced by | Various Voices |

| In-universe information | |

| Nicknames | Silver, Barbeque, Long John, Jack |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | |

| Nationality | English |

Profile

Long John Silver is a cunning and opportunistic pirate who was quartermaster under the notorious Captain Flint. Stevenson's portrayal of Silver has greatly influenced the modern iconography of the pirate.[1]

Silver has a parrot, named Captain Flint in honor—or mockery—of his former captain,[2] who generally perches on Silver's shoulder, and is known to chatter pirate or seafaring phrases like "Pieces of Eight", and "Stand by to go about". Silver uses the parrot as another means of gaining Jim's trust, by telling the boy all manner of exciting stories about the parrot's buccaneer history. "'Now that bird,' Silver would say, 'is, maybe, two hundred years old, Hawkins—they lives forever mostly, and if anybody's seen more wickedness it must be the devil himself. She's sailed with England—the great pirate Cap'n England. She's been at Madagascar, and at Malabar, and Surinam, and Providence, and Portobello... She was at the boarding of the Viceroy of the Indies out of Goa, she was, and to look at her you would think she was a baby."[3]

Silver claims to have served in the Royal Navy and lost his leg under "the immortal Hawke". "His left leg was cut off close by the hip, and under the left shoulder, he carried a crutch, which he managed with wonderful dexterity, hopping about upon it like a bird. He was very tall and strong, with a face as big as a ham—plain and pale, but intelligent and smiling."[4]

He also claims to have been the only man whom Flint ever feared. Like many of Stevenson's characters, there is significant duality in the character; ostensibly Silver is a hardworking and likeable seaman, and it is only as the plot unfolds that his villainous nature is gradually revealed. His relationship with Jim Hawkins, the novel's protagonist and narrator, belies that duality, as he serves as a mentor and eventually father-figure to Jim, creating much shock and emotion when it is discovered that he is in charge of the mutiny, and especially when Jim must confront and fight him later on.

Although treacherous and willing to change sides at any time to further his own interests, Silver has compensating virtues. He is wise enough to save his money, in contrast to the spendthrift ways of most of the pirates. He is physically courageous despite his disability: for instance, when Flint's cache is found to be empty, he coolly stands his ground against five murderous seamen despite having only Jim, a boy in his teens, to back him.

When Silver escapes at the end of the novel, he takes "three or four hundred guineas" of the treasure with him, thus becoming one of only two former members of Captain Flint's crew to get his hands on a portion of the recovered treasure. (The repentant maroonee Ben Gunn is the other, but he spends all £1,000 in nineteen days.) Jim's own ambivalence towards Silver is reflected in the last chapter, when he speculates that the old pirate must have settled down in comfortable retirement: "It is to be hoped so, I suppose, for his chances of comfort in another world are very small."

Silver is married to a woman of African descent, whom he trusts to manage his business affairs in his absence and to liquidate his Bristol assets when his actions make it impossible for him to go home. He confides in his fellow pirates that he and his wife plan to rendezvous after the voyage to Skeleton Island is complete and Flint's treasure is recovered, at which point Silver will retire to a life of luxury. Ironically his "share" of Flint's treasure (£420) is considerably less than that of Ben Gunn (£1,000) and what Silver boasts was his share from England (£900) and from Flint (£2,000).

According to Stevenson's letters, the idea for the character of Long John Silver was inspired by his real-life friend William Henley, a writer and editor.[5] Stevenson's stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, described Henley as "...a great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one's feet".[6] In a letter to Henley after the publication of Treasure Island, Stevenson wrote: "I will now make a confession. It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot Long John Silver...the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you".[7]

Adaptations and related works

Literature

- A prequel novel to Treasure Island, titled Porto Bello Gold, was published in 1924 by Arthur D. Howden Smith.

- British historian Dennis Judd presents Silver as the main character in his 1977 prequel, The Adventures of Long John Silver,[8] and in the 1979 sequel, Return to Treasure Island.[9]

- John Silver is also the protagonist in Björn Larsson's fictional 1995 autobiography, Long John Silver: The True and Eventful History of My Life of Liberty and Adventure as a Gentleman of Fortune and Enemy to Mankind, published in Sweden in 1995.[10]

- Silver is the main character in Edward Chupack's 2008 Silver — My Own Tale as Told by Me with a Goodly Amount of Murder.[11]

Audio-radio

- Orson Welles played Silver in a July 18, 1938 broadcast of The Mercury Theatre on the Air.

- Basil Rathbone starred as both The Narrator and Silver in a 1944 audio recording for Columbia Masterworks Records.[12]

- William Redfield played Silver on the May 14, 1948 Your Playhouse of Favorites adaptation.

- Ronald Colman hosted an adaptation of the novel on the April 27, 1948 broadcast of Favorite Story.[13]

- James Mason played Silver opposite Bobby Driscoll's "Jim Hawkins" on the Lux Radio Theatre's adaptation on January 29, 1951.[14]

- James Kennedy played Silver in the Tale Spinners for Children audio adaptation of Treasure Island (United Artists Records, UAC 11013).[15]

- There have been two BBC Radio adaptations of Treasure Island, with Silver being played by Peter Jeffrey in 1989,[16] and Jack Shepherd in 1995.[17]

- The author John le Carré performed an abridged reading of the novel in five parts as part of BBC Radio 4's Afternoon Reading.[18]

- Tom Baker starred as Silver in Big Finish Productions' 2012 audio adaptation.[19]

Theatre

There have been several major stage adaptations made.[20] The number of minor adaptations remains countless.

- For a time , in London, there was an annual production of the musical Treasure Island, based on a book by Bernard Miles and Josephine Wilson. The music was composed by Cyril Ornadel and the lyrics by Hal Shaper. The musical was performed at the Mermaid Theatre, originally under the direction of Bernard Miles, who played Long John Silver, a part he also played in various television versions. Comedian Spike Milligan would often play Ben Gunn in these productions, and in 1981, Tom Baker played Long John Silver.[21]

- Pieces of Eight, a musical adaptation by Jule Styne, premiered in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1985.

- In 2011, Tom Hewitt starred in B. H. Barry and Vernon Morris's stage adaptation of the novel, which officially opened 5 March at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn.[22]

- In July 2011, Bristol Old Vic staged a large-scale outdoor production of Treasure Island outside the theatre on King Street, Bristol directed by Sally Cookson, with music by Benji Bower.

- From October 2013 to 2014, Mind the Gap Theatre Company held a national tour of Treasure Island, retold by Olivier award-winning writer Mike Kenny.

- In 2013, YouthPlays published Long Joan Silver by Arthur M. Jolly, an adaptation where all of the pirates are women.

- From December 2014 to April 2015, a version by Bryony Lavery and directed by Polly Findlay was produced at London's Royal National Theatre. In this version of the play, Jim is a girl.[23]

- Another Doctor Who alumnus, Arthur Darvill, played Silver in the 2014 National Theatre production of Treasure Island.[24]

- The broadway musical SpongeBob SquarePants: The Broadway Musical features the character in the song "Poor Pirates".

- As part of their 2017 season, the Stratford Festival of Canada premiered a new adaptation of Treasure Island by Canadian playwright Nicolas Billon.

Film

- Charles Ogle played Silver in the 1920 silent film.

- Wallace Beery was the first speaking Long John Silver in the 1934 film.

- Robert Newton became the definitive Long John Silver in the Disney's 1950 live-action film. Born in Dorset in the South West of England, Newton had a broad 'West Country' accent & when this was encouraged & exaggerated by the writers, it became the archetypal 'Pirate voice'.! The phrases "Arrrrrh, matey!" & "Ha, haaar, Jim lad" have become iconic to the way historic pirates are perceived.

The 1954 film, Long John Silver, again starred Robert Newton as the title character, which he would reprise in television (see below).

- The 1971 anime film depicts Silver as an anthropomorphic pig who captains his own pirate ship, sporting a hook prosthesis on his left hand rather than a missing leg.[25]

- In 1971, Boris Andreyev played Silver in the Soviet version Ostrov sokrovishch.

- Orson Welles portrayed Silver in the 1972 live action film adaptation.

- In the 1988 Soviet animated film adaptation, Armen Dzhigarkhanyan provided the voice talent for John Silver.

- In the 1994 movie The Pagemaster, the character of Silver is voiced by Jim Cummings.

- Tim Curry portrays Long John Silver in Disney's 1996 Muppets musical film adaptation.

- Jack Palance, in one of his last film appearances, portrays Silver in the 1999 film.

- Silver is voiced by Brian Murray and depicted as a cyborg in the Disney 2002 animated science fiction adventure film Treasure Planet.

- Lance Henriksen played Silver in the 2006 film Pirates of Treasure Island.

- Tobias Moretti played Silver in the 2007 German film adaptation of Treasure Island, entitled Die Schatzinsel.

- In the film Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018), the character of Tobias Beckett (as played by Woody Harrelson) was inspired by Long John Silver.[26]

Television

- Robert Newton followed up his two feature films with a 1955 Australian-produced television series The Adventures of Long John Silver.[27]

- Peter Wyngarde played Silver in the 1958 TV series The Adventures of Ben Gunn.

- BBC Television has presented the story in miniseries format four times, with the role of Silver being played by Bernard Miles in 1951 and again in 1957;, Peter Vaughan in 1968; and Alfred Burke in 1977. Miles played the role one final time in a 1982 TV movie.

- In 1959, Ivo Garrani played Silver in an Italian television miniseries.

- Ivor Dean played the character in an acclaimed European four-part mini-series in 1966. He intended to reprise the role in another series with more adventures of Silver and began writing it with director Robert S. Baker, but his sudden death in 1974 stopped all further plans. In 1985, the Ivor Dean script was used as foundation for the Disney 10-part TV series Return to Treasure Island, starring Brian Blessed as Long John Silver.

- In the 1978 anime series Takarajima directed by Osamu Dezaki the character is voiced by Genzō Wakayama.

- A 1982 Soviet miniseries had Silver portrayed by Oleg Borisov.

- Anthony Quinn played Silver in the 1987 television miniseries Treasure Island in Outer Space.

- Charlton Heston portrayed a darker Long John Silver in the 1990 made-for-television movie, Treasure Island.

- Eddie Izzard played Long John Silver in the 2012 Sky mini-series.

- Luke Arnold played John Silver in the Starz television series Black Sails (2014–2017), a prequel story set 20 years before Treasure Island. In this series, Silver as a young man begins as a scheming cook who rises to serve as quartermaster on the Walrus and on a captured Spanish Man O' War, later to lead the pirate and former-slave forces that attempt to re-take Nassau from the British. Reflecting his relationship with Jim Hawkins, Silver intends only to use his crewmates to enrich himself, but comes to care for them despite himself. At one point, a rival pirate crew captures the Walrus but, being too few to sail the ship themselves, ask Silver for a list of crew members who can be counted on to shift their loyalties, intending to execute the rest. Silver refuses, and the pirates torture him by repeatedly striking his leg with an ax. The Walrus' crew free themselves and rescue him, but his leg is beyond saving and has to be amputated. He loses consciousness, and wakes to find that a grateful and impressed crew has voted him quartermaster.[28]

- Costas Mandylor portrays "Captain Silver" in the 2016 episode "The Brothers Jones" on ABC's Once Upon a Time.

Other print media

- A Ballad of John Silver, a poem from John Masefield, was published in 1921.[29]

- Long John Silver is a Franco-Belgian comics series written by Xavier Dorison and illustrated by Mathieu Laufray which was published in French and English.[30]

- John Silver, a fictional space pirate with mechanical leg who appears in the Italian comic book Nathan Never, was inspired by Long John Silver.[31]

Other

- The rock band Jefferson Airplane created an album in 1972 named Long John Silver.[32]

- A fast-food seafood restaurant chain, Long John Silver's, is named after the character.[33][34]

References

- Karg, p. 220.

- Stevenson (1883), "The Voyage" [Ch. 10], pp. 80f.

- "Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson". Project Gutenberg. p. Chapter 10. Archived from the original on 2007-05-27.

- (Treasure Island (1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson page 82)

- Prince, p. 78.

- Elwin, p. 154.

- Stevenson (1883), p. 316.

- Burgess, Edwin (1 August 1976). "The Adventures of Long John Silver (Book)". Library Journal. 102: 1678 – via EBSCOhost.

- McKellen, Tess (November 1986). "Return to Treasure Island (Book Review)". School Library Journal. 3: 100 – via EBSCOhost.

- Larsson, Björn (1995). Long John Silver: The True and Eventful History of My Life of Liberty and Adventure as a Gentleman of Fortune and Enemy to Mankind. Geddes, Tom (Transl.). London, ENG: Penguin Random House/Harvill Secker. ISBN 1-86046-538-2. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Chupack, Edward (2008). Silver—My Own Tale as Told by Me with a Goodly Amount of Murder. New York, NY: St. Martin's/Thomas Dunne. ISBN 978-0-312-53936-8. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Basil Rathbone (5 August 2017). "Robert Lewis Stevenson: TREASURE ISLAND" – via Internet Archive.

- "The Definitive Favorite Story Radio Log with Ronald Colman". www.digitaldeliftp.com.

- "Lux Radio Theater - episodic log". www.otrsite.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-05.

- "Tale Spinners for Children". www.artsreformation.com. Archived from the original on 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- "RL Stevenson – Treasure Island – BBC Radio 4 Extra". BBC.

- "Treasure Island (BBC Audiobook Extract) BBC Radio 4 Full-Cast Dramatisation".

- "The Old Sea Dog, Treasure Island, Afternoon Reading – BBC Radio 4". BBC.

- "2. Treasure Island – Big Finish Classics – Big Finish". www.bigfinish.com.

- Dury, Richard. Stage and Radio adaptations of Treasure Island Archived 26 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- "THE THEATRE LINK". thomas-stewart-baker.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-24. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- "Tom Hewitt Is Long John Silver in Treasure Island, Opening March 5 in Brooklyn". Playbill. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Treasure Island". London Box Office. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- "Treasure Island, National Theatre, review: 'yo-ho-hum'".

- Animal Treasure Island (1971)

- Breznican, Anthony (9 February 2018). "Rogue's Gallery: A lineup of three outlaws from Solo: A Star Wars Story". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Storey, Don (2014). "The Adventures of Long John Silver". ClassicAustralianTV.com. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Anderson, D.M. (December 30, 2014). "BLACK SAILS Ain't Your Daddy's Pirate Tale". Moviepilot. Archived from the original on August 31, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- Masefield, John (1921) [1902]. Salt-Water Poems and Ballads. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company. pp. 64–65. Retrieved February 21, 2017. Masefield's original 1902 work was entitled Salt-Water Ballads.

- Dorison, Xavier. Long John Silver (in French). Laufray, Mathieu (Illustr.). Dargaud. Published by Cinebook in English.

- "''Nathan Never – L'isola del tesoro/Treasure Island''". En.sergiobonellieditore.it. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- Bangs, Lester (14 September 1972). "Long John Silver". Rolling Stone. Penske Business Media, LLC. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Long, John. "Long John Silvers/A & W". Sioux City Journal. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Pete, Joseph S. (30 May 2018). "New owners and new look coming to nine Long John Silver's restaurants in Northwest Indiana". The Times of Northwest Indiana. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

Bibliography

- Stevenson, Robert Louis (1883). Treasure Island. Cassell & Company. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Elwin, Malcolm (1939). Old Gods Falling. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 968055.

- Prince, Alison (1994). Kenneth Grahame: An Innocent in the Wild Wood. London: Allison & Busby. ISBN 9780850318296.

- Karg, Barbara; Spaite, Arjean (2007). The Everything Pirates Book: A Swashbuckling History of Adventure on the High Seas. Avon, MA: Adams Media. ISBN 9781598692556.

- Jolly, Arthur M (2013). Long Joan Silver. Los Angeles: YouthPLAYS, Inc. ISBN 9781620882054.

Further reading

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- John Silver on IMDb

- Treasure Island on The Mercury Theatre on the Air: July 18, 1938

- Basil Rathbone stars in Treasure Island: Columbia Masterworks, 1944

- Treasure Island on Lux Radio Theatre: January 29, 1951

- Download Treasure Island on Tale Spinners for Children

- The 1989 BBC Radio Treasure Island on Archive.org