Love Affair (1939 film)

Love Affair is a 1939 American romantic film starring Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer and featuring Maria Ouspenskaya. It was directed by Leo McCarey and written by Delmer Daves and Donald Ogden Stewart, based on a story by McCarey and Mildred Cram.[2] The movie was remade in 1957 as An Affair to Remember, also directed by McCarey, and again with the original title in 1994. A Hindi-languaged version named Mann was released in India in 1999.

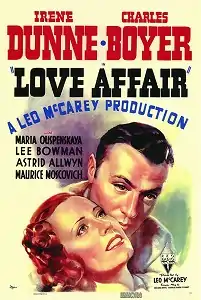

| Love Affair | |

|---|---|

original film poster | |

| Directed by | Leo McCarey |

| Produced by | Leo McCarey |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Roy Webb |

| Cinematography | Rudolph Maté |

| Edited by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $860,000[1] |

| Box office | $1.8 million[1] |

Plot

One December, French painter (and famed womanizer) Michel Marnet (Charles Boyer) meets American singer Terry McKay (Irene Dunne) aboard a liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean. They are both already engaged, he to heiress Lois Clarke (Astrid Allwyn), she to Kenneth Bradley (Lee Bowman). They begin to flirt and to dine together on the ship, but his worldwide reputation makes them conscious that others are watching. Eventually, they decide that they should dine separately and not associate with each other. At a stop at Madeira, they visit Michel's grandmother Janou (Maria Ouspenskaya), who approves of Terry and wants Michel to settle down.

As the ship is ready to disembark at New York City, the two make an appointment to meet in the new year, six months later on top of the Empire State Building, giving Michel enough time to decide whether he can start making enough money to support a relationship with Terry. He finds work selling some paintings and designing advertizing billboards while Terry successfully negotiates a contract with a nightclub to perform through to June. When the rendezvous date arrives, they both head to the Empire State Building. However, Terry is struck by a car on a nearby road, and is told by doctors she may be paralyzed for the rest of her life, though that will not be known for certain for six months. Not wanting to be a burden to Michel, she does not contact him, preferring to let him think the worst. Meanwhile, Michel, who waited until closing time, returns home reluctantly and continues working his two jobs; Terry is overheard singing in the garden of her physiotherapy by the owner of a children's orphanage, who hires her as a music teacher.

Six months go by, and during Terry's first outing since the accident, the two couples meet by accident at the theater, though Terry manages to conceal her condition. On Christmas Eve, Michel visits her at her apartment and finally learns the truth. He assures her that they will be together no matter what the diagnosis will be.

Cast

- Irene Dunne as Terry McKay

- Charles Boyer as Michel Marnet

- Maria Ouspenskaya as Grandmother Janou

- Lee Bowman as Kenneth Bradley

- Astrid Allwyn as Lois Clarke

- Maurice Moscovitch as Maurice Cobert, art dealer

- Scotty Beckett as Boy on Ship (uncredited)

- Dell Henderson as Cafe Manager (uncredited)

- Lloyd Ingraham as Doctor (uncredited)

- Frank McGlynn Sr. as Orphanage Superintendent (uncredited)

Irene Dunne

Irene Dunne Charles Boyer

Charles Boyer Maria Ouspenskaya

Maria Ouspenskaya Lee Bowman

Lee Bowman

Development

Despite the popularity of his romantic and screwball comedies, Leo McCarey had become tired of directing them.[3] His wife suggested they should go on a cruising vacation around Europe to combat his writer's block, and when they returned to the United States, they watched the Statue of Liberty pass. McCarey immediately told her his idea about two passengers who fall in love on a cruise but realize they are both "obligated to somebody else."[4] With the premise created, Mildred Cram co-developed the rest of the story under the working title Love Match,[5][6] as Delmer Daves and Donald Ogden Stewart created the screenplay and dialog with McCarey, respectively.[7] Edward Dmytryk and George Hively were the movie's editors.[8] Filming took place in the fall of 1938.[9] The rough cut was screened in January 1939.[10]

Actresses like Helen Hayes and Greta Garbo developed interest in starring but the McCarey couple preferred Irene Dunne, who had previously appeared in McCarey's The Awful Truth and was a close family friend;[11] Terry's occupation as nightclub singer intended to display Dunne's singing talents.[12] Charles Boyer's reputation as a romantic actor (from starring in History is Made at Night and Algiers) made him McCarey's first choice.[11] Concurrently, Boyer rejected Harry Cohn's offer of the leading role in Good Girls Go to Paris to do Love Affair instead.[13] He and McCarey were acquaintances and Boyer believed McCarey was an underestimated director,[14] so he canceled many acting plans for the rest of 1938 to work with McCarey and Dunne.[15]

There was no official script when the movie went into production. Irene Dunne later noted that the dialog would change frequently and the cast would receive pieces of paper between filming; McCarey's common directing tactic of improvization also continued throughout.[16] However, McCarey gave Dunne the opportunity to choose the signature song for the movie: she decided upon "Wishing,"[11] which became one of the most popular songs of 1939;[10] the orphans were dubbed by Robert Mitchell's Boys Choir.[10] Boyer was allowed input in Michel's characterization; he suggested that Michel visiting his grandmother should have a prominent appearance so Terry's accident would not create a tonal shift.[7]

Maria Ouspenskaya described working on the film as "an atmosphere of work that is inspirational. [...] Actor, electricians, and cameramen loved their work and did not want to break away from that atmosphere."[17] Boyer would later praise McCarey's filmmaking for the movie's success; he was described in an interview years later as "still speak[ing] of Mr. McCarey with sincere awe."[18]

Release

Film Daily reported that Love Affair's release had the potential to be premiered in late January or early February 1939 at Radio City Music Hall;[19] later issues would give the initial release date as February 17 and March 10.[20][Note 1] The film premiered March 16 at the Music Hall with a pink champagne-themed cocktail party for Dunne, emceed by W. G. Van Schmus; McCarey was on vacation in Santa Monica and could not attend.[22]

Reception

The praise for Love Affair among film critics reflected in Clark Wales' quip: "Recommending a Leo McCarey production is something like recommending a million dollars or beauty or a long and happy life. Any of these is a very fine thing to have and the only trouble is that there are not enough of them."[23] New York World-Telegram called the film "the most absorbing and delightful entertainment of its kind [in] a long time"[24] and another called the film "tender, poignant [and] sentimental without being gooey".[25] "Put this one down among the contenders of the Academy Awards of 1939," declared The Associated Press, "and [one] of the most satisfactory movie endings."[26]

"The screenplay is an exceptionally intelligent effort," wrote the Box Office Digest, "[and] McCarey's skill in handling individual scenes with the old Roach technique carries through this tough spot and on to a grand climax."[27] But the review added: "It must be unfortunately recorded that there is a let down in interest for a half reel when [Michel and Terry] are separated."[27]

On characterization, The New York Times remarked on "the facility with which [Boyer and Dunne] have matched the changes of their script—playing it lightly with a superb utilization of the material at hand."[28] Leo Mishkin added: "Certainly, this Terry McKay of Miss Dunne's is one of the greatest things she has ever done on the screen[.]"[29] Variety described Boyer's performance of Michel as "a particularly effective presentation of the modern Casanova."[30] Box Office Digest wrote, "[Boyer and Dunne have] never done more delightful work, and to say that they step along in stride — step for step, is a tribute to either one in red hot competition."[27] The Film Daily described the performances as "gorgeously acted" and "stand[s] out as the best of many months."[31] The only notable criticism of characters came from Dunne herself, who told Silver Screen years later: "If I had been in that girl's place, far from hiding, I would've trundled my wheelchair up and down the sidewalks of New York looking for [Michel]."[32]

Love Affair was RKO Pictures' second-popular film, after Gunga Din.[33]

Adaptations

Plans for a Love Affair remake were first reported in 1952, which had Fernando Lamas and Arlene Dahl attached to the project.[34] Eventually, McCarey remade it in 1957 as An Affair to Remember with Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr in the lead roles, using a very similar screenplay.

Glenn Gordon Caron also remade the film in 1994 as Love Affair, starring Warren Beatty, Annette Bening and, in her last feature film, Katharine Hepburn.[35]

Bollywood cinema made two versions: 1965's Bheegi Raat and 1999's Mann, which were both adaptations of An Affair to Remember.

Accolades

12th Academy Awards

- Nominations[36]

- Outstanding Production: RKO Radio

- Best Actress: Irene Dunne

- Best Supporting Actress: Maria Ouspenskaya

- Best Writing (Original Story): Mildred Cram, Leo McCarey

- Best Art Direction: Van Nest Polglase, Al Herman

- Best Original Song: "Wishing," music and lyrics by Buddy DeSylva[30]

Availability

In 1967, the film entered the public domain in the United States because the claimants did not renew its copyright registration in the 28th year after publication.[37] Because of this, the film is widely available on home video and online. The film can be downloaded legally for free on the Internet Archive.

Notes

- Film Daily marked the March 10 date as a pre-release.[21]

References

- Richard Jewel (1994). "RKO Film Grosses: 1931-1951". Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television. 14 (1): 56.

- "Love Affair 1939". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- Creelman, Eileen (November 3, 1937). "Leo McCarey Tells of Directing Irene Dunne in a New Comedy "The Awful Truth"". New York Sun.

However the public may feel about charmingly insane people on screen, Leo McCarey is fed up with them.

- Bogdanovich, Peter (1997). Who the Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors. New York: Bellantine Books. pp. 417–418.

- "In the Cutting Room". Motion Picture Herald. Quigley Publishing Co. November 5, 1938. p. 27.

- "The Hollywood Scene". Motion Picture Herald. Quigley Publishing Co. October 8, 1938. p. 31.

- Swindell, Larry (1983). Charles Boyer: The Reluctant Lover (first ed.). Garden City, N.Y. p. 143. ISBN 0385170521.

- "Cumulative Copyright Catalog". Motion Picture 1912-1939: 409 – via Internet Archive.

- Swindell, Larry (1983). Charles Boyer: The Reluctant Lover (First ed.). Garden City, N.Y. p. 140. ISBN 0385170521.

- Swindell, Larry (1983). Charles Boyer: The Reluctant Lover (first ed.). Garden City, N.Y. p. 144. ISBN 0385170521.

- Gehring, Wes D. (2003). Irene Dunne: First Lady of Hollywood. pp. 100–103. ISBN 978-0810858640.

- Gehring, Wes D. (2005). "A Cowboy, A Cruise, A Crash and A Cary". Leo McCarey: From Marx to McCarthy. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 159. ISBN 0810852632.

- Swindell, Larry (1983). Charles Boyer: The Reluctant Lover (first ed.). Garden City, N.Y. p. 130. ISBN 0385170521.

- Swindell, Larry (1983). Charles Boyer: The Reluctant Lover (first ed.). Garden City, N.Y. p. 139. ISBN 0385170521.

- Swindell, Larry (1983). Charles Boyer: The Reluctant Lover (first ed.). Garden City, N.Y. p. 140. ISBN 0385170521.

- Dunne, Irene (1972). "Interview with John Kobal". People Will Talk (Interview). Interviewed by John Kobal. Alfred A. Knopf (January 1, 1986).

- Crewe, Regina (March 19, 1939). "Mme Ouspenskaya, back from Coast, Offers Helping Hand to Fledglings". New York Journal.

- O'Liam, Dugal (March 1943). "Boyer's Double Life!". Screenland. XLVI (5). Screenland Magazine, inc. p. 88.

- Baun, Chester B. (January 20, 1939). "Less Grousing ... More Selling". The Film Daily. Wid's Films and Film Folk, inc. p. 1.

- "A Calendar of Feature Releases". The Film Daily. January 27, 1939. p. 8.

- "6 RKO March Releases". The Film Daily. March 3, 1939. p. 2.

- Daly, Phil M. (March 17, 1939). "Along the Rialto". The Film Daily. p. 3.

- Clark Wales (March 1939). "Love Affair review". Detroit Free Press: Screen and Radio Weekly. p. 5.

- Boehnel, William (March 17, 1939). "Love Affair Seen as Outstanding Film". New York World-Telegram. p. 23.

- Cameron, Kate (March 17, 1939). "Exquisite Romance on Music Hall Screen". New York Daily News. p. 48.

- "[advertizing spread]". The Film Daily. March 14, 1939. pp. 8–9.

- ""Love Affair" Shows Dunne-Boyer at Best". Box Office Digest. Los Angeles, National Box Office Digest. March 11, 1939. p. 7.

- Nugent, Frank S. (March 17, 1939). "Love Affair". New York Times. p. 26.

- Mishkin, Leo (March 18, 1939). "Love Affair a Music Hall Winner; Irene Dunne, Charles Boyer Superb". The New York Telegraph. p. 2.

- "Love Affair (with Songs)". Variety. March 15, 1939. p. 16.

- "Love Affair with Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne". The Film Daily. March 13, 1939. p. 10.

- Faith Service (1944). "My Screen Selves and I". Silver Screen. No. August 1944. pp. 60–61.

- "RADIO'S "LOVE AFFAIR" HITS AT BOX OFFICE; PARAMOUNT'S "MIDNIGHT" IN SECOND SPOT". Box Office Digest. 9 (9). April 3, 1939. p. 5.

- Hyams, Joe (November 5, 1952). "Entertainment in the News". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. p. 14.

- "Love Affair 1994". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- "The 12th Academy Awards | 1940". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018.

- Pierce, David (June 2007). "Forgotten Faces: Why Some of Our Cinema Heritage Is Part of the Public Domain". Film History: An International Journal. 19 (2): 125–43. doi:10.2979/FIL.2007.19.2.125. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 25165419. OCLC 15122313. S2CID 191633078.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Love Affair (film). |

- Love Affair at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Love Affair at IMDb

- Love Affair at Rotten Tomatoes

- Love Affair is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Love Affair at the TCM Movie Database

- Love Affair at AllMovie

Streaming audio

- Love Affair on Lux Radio Theater: April 1, 1940

- Love Affair on Lux Radio Theater: July 6, 1942