M1 Garand

The M1 Garand[nb 1] is a .30-06 caliber semi-automatic rifle that was the standard U.S. service rifle during World War II and the Korean War and also saw limited service during the Vietnam War. Most M1 rifles were issued to U.S. forces, though many hundreds of thousands were also provided as foreign aid to American allies. The Garand is still used by drill teams and military honor guards. It is also widely used by civilians for hunting, target shooting, and as a military collectible.

| U.S. rifle, caliber .30, M1 | |

|---|---|

M1 Garand rifle from the collection of the Swedish Army Museum, Stockholm, Sweden | |

| Type | Semi-automatic rifle |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1936–1958 (as the standard U.S. service rifle) 1940s–present (other countries) |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars |

|

| Production history | |

| Designer | John C. Garand |

| Designed | 1928 |

| Manufacturer |

|

| Unit cost | About $85 (during World War II) $ 1260 current equivalent |

| Produced | 1934—1957 |

| No. built | 5,468,772[9] |

| Variants | M1C, M1D |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 9.5 lb (4.31 kg) to 11.6 lb (5.3 kg) |

| Length | 43.5 in (1,100 mm) |

| Barrel length | 24 in (609.6 mm) |

| Cartridge |

|

| Action | Gas-operated, rotating bolt |

| Rate of fire | 40–50 rounds/min |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,800 ft/s (853 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 500 yd (457 m)[10] |

| Feed system | 8-round en bloc clip, internal magazine |

| Sights |

|

The M1 rifle was named after its Canadian-American designer, John Garand. It was the first standard-issue semi-automatic military rifle.[11] By most accounts, the M1 rifle performed well. General George S. Patton called it "the greatest battle implement ever devised".[12][13] The M1 replaced the bolt-action M1903 Springfield as the standard U.S. service rifle in 1936,[14] and was itself replaced by the selective fire M14 rifle on March 26, 1958.[15]

Although the name "Garand" is frequently pronounced /ɡəˈrænd/, the preferred pronunciation is /ˈɡærənd/ (to rhyme with errand), according to experts and people who knew John Garand, the weapon's designer.[16][17] Frequently referred to as the "Garand" or "M1 Garand" by civilians, its official designation when it was the issue rifle in the U.S. Army and the U.S. Marine Corps was "U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1" or just "M1" and Garand was not mentioned.

History

Development

French Canadian-born Garand went to work at the United States Army's Springfield Armory and began working on a .30 caliber primer actuated blowback Model 1919 prototype. In 1924, twenty-four rifles, identified as "M1922s", were built at Springfield. At Fort Benning during 1925, they were tested against models by Berthier, Hatcher-Bang, Thompson, and Pedersen, the latter two being delayed blowback types.[18] This led to a further trial of an improved "M1924" Garand against the Thompson, ultimately producing an inconclusive report.[18] As a result, the Ordnance Board ordered a .30-06 Garand variant. In March 1927, the cavalry board reported trials among the Thompson, Garand, and 03 Springfield had not led to a clear winner. This led to a gas-operated .276 (7 mm) model (patented by Garand on 12 April 1930).[18]

In early 1928, both the infantry and cavalry boards ran trials with the .276 Pedersen T1 rifle, calling it "highly promising"[18] (despite its use of waxed ammunition,[19] shared by the Thompson).[20] On 13 August 1928, a semiautomatic rifle board (SRB) carried out joint Army, Navy, and Marine Corps trials between the .30 Thompson, both cavalry and infantry versions of the T1 Pedersen, "M1924" Garand, and .256 Bang, and on 21 September, the board reported no clear winner. The .30 Garand, however, was dropped in favor of the .276.[21]

Further tests by the SRB in July 1929, which included rifle designs by Browning, Colt–Browning, Garand, Holek, Pedersen, Rheinmetall, Thompson, and an incomplete one by White,[nb 2] led to a recommendation that work on the (dropped) .30 gas-operated Garand be resumed, and a T1E1 was ordered 14 November 1929.

Twenty gas-operated .276 T3E2 Garands were made and competed with T1 Pedersen rifles in early 1931. The .276 Garand was the clear winner of these trials. The .30 caliber Garand was also tested, in the form of a single T1E1, but was withdrawn with a cracked bolt on 9 October 1931. A 4 January 1932 meeting recommended adoption of the .276 caliber and production of approximately 125 T3E2s. Meanwhile, Garand redesigned his bolt and his improved T1E2 rifle was retested. The day after the successful conclusion of this test, Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur personally disapproved any caliber change, in part because there were extensive existing stocks of .30 M1 ball ammunition.[22] On 25 February 1932, Adjutant General John B. Shuman, speaking for the Secretary of War, ordered work on the rifles and ammunition in .276 caliber cease immediately and completely, and all resources be directed toward identification and correction of deficiencies in the Garand .30 caliber.[20]:111

On 3 August 1933, the T1E2 became the "semi-automatic rifle, caliber 30, M1".[18] In May 1934, 75 M1s went to field trials; 50 went to infantry, 25 to cavalry units.[20]:113 Numerous problems were reported, forcing the rifle to be modified, yet again, before it could be recommended for service and cleared for procurement on 7 November 1935, then standardized 9 January 1936.[18] The first production model was successfully proof-fired, function-fired, and fired for accuracy on July 21, 1937.[23]

Production difficulties delayed deliveries to the Army until September 1937. Machine production began at Springfield Armory that month at a rate of ten rifles per day,[24] and reached an output of 100 per day within two years. Despite going into production status, design issues were not at an end. The barrel, gas cylinder, and front sight assembly were redesigned and entered production in early 1940. Existing "gas-trap" rifles were recalled and retrofitted, mirroring problems with the earlier M1903 Springfield rifle that also had to be recalled and reworked approximately three years into production and foreshadowing rework of the M16 rifle at a similar point in its development. Production of the Garand increased in 1940 despite these difficulties,[25] reaching 600 a day by 10 January 1941,[18] and the Army was fully equipped by the end of 1941.[22] Following the outbreak of World War II in Europe, Winchester was awarded an "educational" production contract for 65,000 rifles,[18] with deliveries beginning in 1943.[18]

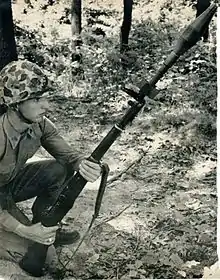

Service use

The M1 Garand was made in large numbers during World War II; approximately 5.4 million were made.[26] They were used by every branch of the United States military. The rifle generally performed well. General George S. Patton called it "the greatest battle implement ever devised."[13] The impact of faster-firing infantry small arms in general soon stimulated both Allied and Axis forces to greatly increase their issue of semi- and fully automatic firearms then in production, as well as to develop new types of infantry firearms.[27]

Many M1s were repaired or rebuilt after World War II. While U.S. forces were still engaged in the Korean War, the Department of Defense decided more were needed. Springfield Armory ramped up production, but two new contracts were awarded. During 1953–56, M1s were produced by International Harvester and Harrington & Richardson in which International Harvester alone produced a total of 337,623 M1 Garands.[28][29] A final, very small lot of M1s was produced by Springfield Armory in early 1957, using finished components already on hand. Beretta also produced Garands using Winchester tooling.

The British Army looked at the M1 as a possible replacement for its bolt-action Lee–Enfield No.1 Mk III, but it was rejected when rigorous testing suggested that it was an unreliable weapon in muddy conditions. However, surplus M1 rifles were provided as foreign aid to American allies, including South Korea, West Germany, Italy, Japan, Denmark, Greece, Turkey, Iran, South Vietnam, the Philippines, etc. Most Garands shipped to allied nations were predominantly manufactured by International Harvester Corporation during the period of 1953–56, and second from Springfield Armory from all periods.[29]

Some Garands were still being used by the United States into the Vietnam War in 1963; despite the M14's official adoption in 1958, it was not until 1965 that the changeover from the M1 Garand was fully completed in the active-duty component of the Army (with the exception of the sniper variants, which were introduced in World War II and saw action in Korea and Vietnam). The Garand remained in service with the Army Reserve, Army National Guard and the Navy into the early 1970s. The South Korean Army was using M1 Garands in the Vietnam War as late as 1966.[30]

Due to widespread United States military assistance as well their durability, M1 Garands have also been found in use in recent conflicts such as with the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan.[31]

Some military drill teams still use the M1 rifle, including the U.S. Marine Corps Silent Drill Team, the United States Air Force Academy Cadet Honor Guard, the U.S. Air Force Auxiliary, almost all Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) and some Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) teams of all branches of the U.S. military.

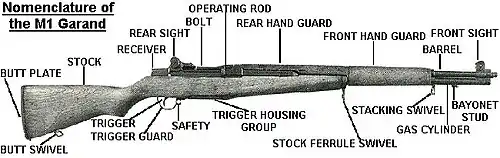

Design details

Features

The M1 rifle is a .30 caliber, gas-operated, 8 shot clip-fed, semi-automatic rifle.[32] It is 43.6 inches (1,107 mm) long and it weighs about 9.5 pounds (4.31 kg).[33]

The M1's safety catch is located at the front of the trigger guard. It is engaged when it is pressed rearward into the trigger guard, and disengaged when it is pushed forward and is protruding outside of the trigger guard.[34]

The M1 Garand was designed for simple assembly and disassembly to facilitate field maintenance. It can be field stripped (broken down) without tools in just a few seconds.[35]

The rifle had an iron sight line consisting of rear receiver aperture sight protected by sturdy "ears" calibrated for 100–1,200 yd (91–1,097 m) in 100 yd (91 m) increments. The bullet drop compensation was set by turning the range knob to the appropriate range setting. The bullet drop compensation/range knob can be fine adjusted by setting the rear sight elevation pinion. The elevation pinion can be fine adjusted in approximately 1 MOA increments. The aperture sight was also able to correct for wind drift operated by turning a windage knob that moved the sight in approximately 1 MOA increments. The windage lines on the receiver to indicate the windage setting were 4 MOA apart. The front sighting element consisted of a wing guards protected front post.

During World War II the M1 rifle's semiautomatic operation gave United States infantrymen a significant advantage in firepower and shot-to-shot recovery time over enemy infantrymen armed primarily with bolt-action rifles. The semi-automatic operation and reduced recoil allowed soldiers to fire 8 rounds as quickly as they could pull the trigger, without having to move their hands on the rifle and therefore disrupt their firing position and point of aim.[36] The Garand's fire rate, in the hands of a trained soldier, averaged 40–50 accurate shots per minute at a range of 300 yards (270 m). "At ranges over 500 yards (460 m), a battlefield target is hard for the average rifleman to hit. Therefore, 500 yards (460 m) is considered the maximum effective range, even though the rifle is accurate at much greater ranges."[33]

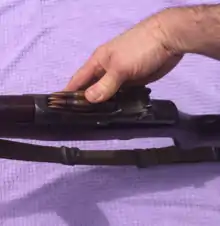

En bloc clip

The M1 rifle is fed by an en bloc clip which holds eight rounds of .30-06 Springfield ammunition. When the last cartridge is fired, the rifle ejects the clip and locks the bolt open.[37] The M1 is then ready to reload. Once the clip is inserted, the bolt snaps forward on its own as soon as thumb pressure is released from the top round of the clip, chambering a round and leaving it ready to fire.[38][39] Although it is not absolutely necessary, the preferred method is to place the back of the right hand against the operating rod handle and press the clip home with the right thumb; this releases the bolt, but the hand restrains the bolt from slamming closed on the operator's thumb (resulting in "M1/Garand thumb"); the hand is then quickly withdrawn, the operating rod moves forward and the bolt closes with sufficient force to go fully to battery. Thus, after the clip has been pressed into position in the magazine, the operating rod handle should be released, allowing the bolt to snap forward under pressure from the operating rod spring. The operating rod handle may be smacked with the palm to ensure the bolt is closed.[34][39]

Contrary to widespread misconception, partially expended or full clips can be easily ejected from the rifle by means of the clip latch button.[34] It is also possible to load single cartridges into a partially loaded clip while the clip is still in the magazine, but this requires both hands and a bit of practice. In reality, this procedure was rarely performed in combat, as the danger of loading dirt along with the cartridges increased the chances of malfunction. Instead, it was much easier and quicker to simply manually eject the clip, and insert a fresh one,[40] which is how the rifle was originally designed to be operated.[39][41][42] Later, special clips holding two or five rounds became available on the civilian market, as well as a single-loading device which stays in the rifle when the bolt locks back.

In battle, the manual of arms called for the rifle to be fired until empty, and then recharged quickly. Due to the well-developed logistical system of the U.S. military at the time, this consumption of ammunition was generally not critical, though this could change in the case of units that came under intense fire or were flanked or surrounded by enemy forces.[41] The Garand's en bloc clip system proved particularly cumbersome when using the rifle to launch grenades, requiring removal of an often partially loaded clip of ball ammunition and replacement with a full clip of blank cartridges.

By modern standards, the M1's feeding system is archaic, relying on clips to feed ammunition, and is the principal source of criticism of the rifle. Officials in Army Ordnance circles demanded a fixed, non-protruding magazine for the new service rifle. At the time, it was believed that a detachable magazine on a general-issue service rifle would be easily lost by U.S. soldiers (a criticism made of British soldiers and the Lee–Enfield 50 years previously), would render the weapon too susceptible to clogging from dirt and debris (a belief that proved unfounded with the adoption of the M1 Carbine), and that a protruding magazine would complicate existing manual-of-arms drills. As a result, inventor John Garand developed an en bloc clip system that allowed ammunition to be inserted from above, clip included, into the fixed magazine. While this design provided the requisite flush-mount magazine, the clip system increased the rifle's weight and complexity, and made only single loading ammunition possible without a clip.

Ejection of an empty clip created a distinctive metallic "pinging" sound.[43] In World War II, it was rumored that German and Japanese infantry were making use of this noise in combat to alert them to an empty M1 rifle in order to catch their American enemies with an unloaded rifle. It was reported that the U.S. Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground began experiments with clips made of various plastics in order to soften the sound, though no improved clips were ever adopted.[42] However, this claim regarding the risks of a pinging empty clip is questionable due to hearsay produced as fact by the only known source, the otherwise fairly reliable author Roy F. Dunlap in Ordnance Went Up Front in 1948. According to former German soldiers, the sound was inaudible during engagements and not particularly useful when heard, as other squad members might have been nearby ready to fire.[44] Due to the often intense deafening noise of combat and gunfire it is highly unlikely any U.S. servicemen were killed as a result of the ping noise; however some soldiers still took the issue very seriously.[45]

Gas system

Garand's original design for the M1 used a complicated gas system involving a special muzzle extension gas trap, later dropped in favor of a simpler drilled gas port. Because most of the older rifles were retrofitted, pre-1939 gas-trap M1s are very rare today and are prized collector's items.[32] In both systems, expanding gases from a fired cartridge are diverted into the gas cylinder. Here, the gases meet a long-stroke piston attached to the operating rod, which is pushed rearward by the force of this high-pressure gas. Then, the operating rod engages a rotating bolt inside the receiver. The bolt is locked into the receiver via two locking lugs, which rotate, unlock, and initiate the ejection of the spent cartridge and the reloading cycle when the rifle is discharged. The operating rod (and subsequently the bolt) then returns to its original position.

The M1 Garand was one of the first self-loading rifles to use stainless steel for its gas tube, in an effort to prevent corrosion. As the stainless metal could not be parkerized, the gas tubes were given a stove-blackening that frequently wore off in use. Unless the gas tube could be quickly repainted, the resultant gleaming muzzle could make the M1 Garand and its user more visible to the enemy in combat.[41]

Accessories

Several accessories were used with the Garand rifle. Several different styles of bayonets fit the rifle: the M1905, with a 16-inch (406 mm) blade; the M1 with a 10-inch (254 mm) blade (either made standard or shortened from existing M1905 bayonets); and the M5 bayonet with 6.75-inch (171 mm) blade.

Also available was the M7 grenade launcher that could easily be attached to the end of the barrel.[46][47] It could be sighted using the M15 sight, which was attached with screws to the left side of the stock, just forward of the trigger. A cleaning tool, oiler and grease containers could be stored in two cylindrical compartments in the buttstock for use in the field.

The M1907 two-piece leather rifle sling was the most common type of sling used with the weapon through World War II. In 1942, an olive drab canvas sling was introduced that gradually became more common.[48] Another accessory was the winter trigger, developed during the Korean War.[49] It consisted of a small mechanism installed on the trigger guard, allowing the soldier to remotely pull the trigger by depressing a lever just behind the guard.[49] This enabled the shooter to fire his weapon while using winter gloves, which could get "stuck" on the trigger guard or not allow for proper movement of the finger.[49]

Variants

Sniper models

Most variants of the Garand, save the sniper variants, never saw active duty.[43] The sniper versions were modified to accept scope mounts, and two versions (the M1C, formerly M1E7, and the M1D, formerly M1E8) were produced, although not in significant quantities during World War II.[50] The only difference between the two versions is the mounting system for the telescopic sight. In June 1944, the M1C was adopted as a standard sniper rifle by the U.S. Army to supplement the venerable M1903A4, but few saw combat; wartime production was only 7,971 M1Cs.[51]

The procedure required to install the M1C-type mounts through drilling/tapping the hardened receiver reduced accuracy by warping the receiver. Improved methods to avoid reduction of accuracy were inefficient in terms of tooling and time. This resulted in the development of the M1D, which utilized a simpler, single-ring Springfield Armory mount attached to the barrel rather than the receiver. The M1C was first widely used during the Korean War. Korean War production was 4,796 M1Cs and 21,380 M1Ds; although few M1Ds were completed in time to see combat.[51]

The U.S. Marine Corps adopted the M1C as their official sniper rifle in 1951. This USMC 1952 Sniper's Rifle or MC52 was an M1C with the commercial Stith Bear Cub scope manufactured by the Kollmorgen Optical Company under the military designation: Telescopic Sight - Model 4XD-USMC. The Kollmorgen scope with a slightly modified Griffin & Howe mount was designated MC-1. The MC52 was also too late to see extensive combat in Korea, but it remained in Marine Corps inventories until replaced by bolt-action rifles during the Vietnam War.[51] The U.S. Navy has also used the Garand, rechambered for the 7.62×51mm NATO round.

The detachable M2 conical flash hider adopted 25 January 1945 slipped over the muzzle and was secured in place by the bayonet lug. A T37 flash hider was developed later. Flash hiders were of limited utility during low-light conditions around dawn and dusk, but were often removed as potentially detrimental to accuracy.[51]

Tanker models

Two interesting variants, meant for tank crews, that never saw service were the M1E5 and T26 (popularly known as the Tanker Garand). The M1E5 is equipped with a shorter 18-inch (457 mm) barrel and a folding buttstock, while the T26 uses a shorter 18-inch (457 mm) barrel and a standard buttstock. The Tanker name was also used after the war as a marketing gimmick for commercially modified Garands.

The T26 arose from requests by various Army combat commands for a shortened version of the standard M1 rifle for use in jungle or mobile warfare. In July 1945 Col. William Alexander, former staff officer for Gen. Simon Buckner and a new member of the Pacific Warfare Board,[52] requested urgent production of 15,000 carbine-length M1 rifles for use in the Pacific theater.[53][54][55][56] To emphasize the need for rapid action, he requested the Ordnance arm of the U.S. 6th Army in the Philippines to make up 150 18" barreled M1 rifles for service trials, sending another of the rifles by special courier to U.S. Army Ordnance officials at Aberdeen as a demonstration that the M1 could be easily modified to the new configuration.[53][55][54][56] Although the T26 was never approved for production, at least one 18" barreled M1 rifle was used in action in the Philippines by troopers in the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (503rd PIR).[56]

T20E2

Another variant that never saw duty was the T20E2. It was an experimental gas-operated, selective fire rifle with a slightly longer receiver than the M1 and modified to accept 20-round Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) magazines. The rifle was machined and tapped on the left side of the receiver for a scope mount, and included the same hardware for mounting a grenade launcher as the M1. The bolt had a hold open device on the rear receiver bridge, as well as a fire selector similar to the M14. Full automatic fire was achieved by a connector assembly which was actuated by the operating rod handle. This, in turn, actuated a sear release or trip which, with the trigger held to the rear, disengaged the sear from the hammer lugs immediately after the bolt was locked. In automatic firing, the cyclic rate of fire was 700 rpm. When the connector assembly was disengaged, the rifle could only be fired semi-automatically and functioned in a manner similar to the M1 rifle. The T20 had an overall length of 48 1/4", a barrel length of 24", and weighed 9.61 lbs. without accessories and 12.5 lbs. with bipod and empty magazine. It was designated as limited procurement in May, 1945. Due to the cessation of hostilities with Japan, the number for manufacture was reduced to 100. The project was terminated in March 1948.

Quick reference

| U.S. Army designation | U.S. Navy designation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | N/A | Prototype |

| T1E1 | N/A | A single trial rifle that broke its bolt in the 1931 trial |

| T1E2 | N/A | Trial designation for gas-trap Garand. Basically a T1E1 with a new bolt. |

| M1 | N/A | Basic model. Identical to T1E2. Later change to gas port did not change designation |

| M1E1 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; modified cam angle in op-rod |

| M1E2 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; prismatic scope and mount |

| M1E3 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; roller added to bolt's cam lug (later adapted for use in the M14) |

| M1E4 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; gas cut-off and expansion system with piston integral to op-rod |

| M1E5 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; 18-inch (457 mm) barrel and folding stock, for Airborne and Tank crewman use. |

| M1E6 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; sniper variant |

| M1E7/M1C | N/A | M1E6 Garand variant; M1C sniper variant with 2.2× magnification M73 scope (later modified as the M81, though the M82 or M84 scope could be used) in a Griffin & Howe mount affixed to the left side of the receiver requiring a leather cheek pad to properly position the shooter's face behind the offset scope[51] |

| M1E8/M1D | N/A | M1E7 Garand variant; M1D sniper variant with M82 scope (though the M84 scope could be used) in a Springfield Armory mount attached to the rear of the barrel allowing quick removal of the scope but similarly requiring the leather cheek pad[51] |

| M1E9 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; similar to M1E4, with piston separate from op-rod |

| M1E10 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; variant with the Ljungman direct gas system |

| M1E11 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; short-stroke Tappet gas system |

| M1E12 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; gas impingement system |

| M1E13 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; "White" gas cut-off and expansion system |

| M1E14 | Mk 2 Mod 0 | M1 Garand variant; rechambered in 7.62×51mm NATO with press-in chamber insert, enlarged gas port, and 7.62mm barrel bushing.[57] |

| T20 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; select-fire conversion by John Garand, capable of using BAR magazines |

| T20E1 | N/A | T20 variant; uses its own type of magazines |

| T20E2 | N/A | T20 variant; E2 magazines will work in BAR, but not the reverse |

| T20E2HB | N/A | T20E2 variant; HBAR (heavy barrel) variant |

| T22 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; fully automatic select-fire conversion by Remington, magazine-fed |

| T22E1 | N/A | T22 variant; unknown differences |

| T22E2 | N/A | T22 variant; unknown differences |

| T22E3HB | N/A | T22 variant; stock angled upwards to reduce muzzle climb; heavy barrel; uses T27 fire control |

| T23 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; upward angled stock like T22E3HB; standard clip fed. |

| T25 | N/A | T25 variant had a pistol grip: the stock angled upwards to reduce muzzle climb; and chambered for the new T65 .30 Light Rifle cartridge (7.62×49mm).[58] |

| T26 | N/A | M1 Garand variant; 18-inch (457 mm) barrel and standard stock, for airborne and tank crewman use. |

| T27 | N/A | Remington select-fire field conversion for M1 Garand; ability to convert issue M1 Garands to select-fire rifles; fire control setup used in T22E3 |

| T31 | N/A | Experimental bullpup variant |

| T35 | Mk 2 Mod 1 | M1 Garand variant; rechambered for 7.62×51mm NATO; While the majority used the standard en bloc clip, a small number were experimentally fitted with a 10-round internal magazine loaded by 5-round stripper clips. |

| T36 | N/A | T20E2 variant; rechambered for 7.62×51mm NATO using T35 barrel and T25 magazine |

| T37 | N/A | T36 variant; same as T36, except in gas port location |

| T44 | N/A | T44 variant; was a conventional design developed on a shoestring budget as an alternative to the T47.[58] With only minimal funds available, the earliest T44 prototypes simply used T20E2 receivers fitted with magazine filler blocks and re-barreled for 7.62×51mm NATO, with the long operating rod/piston of the M1 replaced by the T47's gas cut-off system.[58] |

| T47 | N/A | T47 variant; same as the T25, except for a conventional stock and chambered for 7.62×51mm NATO.[58] |

Demilitarized versions

Demilitarized models are rendered permanently inoperable. Their barrels have been drilled out to destroy the rifling. A steel rod is then inserted into the barrel and welded at both ends. Sometimes, their barrels are also filled with molten lead or solder. Their gas ports or operating system are also welded closed. Their barrels are then welded to their receivers to prevent replacement. Their firing pin holes are welded closed on the bolt face. As a result, they cannot be loaded with, much less fire live ammunition. However, they may still be used for demonstration or instructional purposes.

| Nomenclature | National Stock Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Rifle, Inert, Caliber .30, M1 |

1005-00-599-3289 | Demilitarized and barrel plugged. US Air Force instructional use. |

| Rifle, Training Aid, Caliber .30, M1 | 1005-01-061-2456 | Demilitarized and barrel plugged. Instructional use. |

| Rifle, Dummy Drill, Caliber .30, M1 | 1005-01-113-3767 | Demilitarized. Barrel is unplugged but is welded to the receiver. ROTC instructional use. |

| Rifle, Ceremonial, Caliber .30, M1 | 1005-01-095-0085 | Gas cylinder lock valve is removed and the gas system has welds permanently joining the lock and gas cylinder to prevent reversion. Barrel is unplugged but is welded to the receiver. The weapon has been converted from semi-automatic to a repeater and can only fire blanks. The bolt must be cycled to eject the spent cartridge case and reload a fresh round from the internal clip. Used by American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars honor guards for parading and firing ceremonial salutes. |

Copies and postwar derivatives

Japanese Type 4

The Type 4 Rifle, often referred to as the Type 5 Rifle (Japanese: 四式自動小銃 Yon-shiki jidousyoujyuu), was a Japanese experimental semi-automatic rifle.[59] It was a copy of the American M1 Garand but with an integral 10-round magazine and chambered for the Japanese 7.7×58mm Arisaka cartridge.[60] Where the Garand used an en bloc clip, the Type 4's integral magazine was charged with two 5-round stripper clips and the rifle also used Japanese style tangent sights. The Type 4 had been developed alongside several other experimental semi-automatic rifles. However, none of the rifles entered into service before the end of World War II, with only 250 being made and many others were never assembled. There were several problems with jamming and feed systems, which also delayed its testing.

Beretta Models

During the 1950s, Beretta produced Garands in Italy at the behest of NATO, by having the tooling used by Winchester during World War II shipped to them by the U.S. government. These rifles were designated Model 1952 in Italy. Using this tooling, Beretta developed the BM59 series of rifles. The BM59, which was essentially a rechambered 7.62×51mm NATO caliber M1 fitted with a removable 20-round magazine, folding bipod and a combined flash suppressor/rifle grenade launcher. The BM59 is capable of selective fire. These rifles would also be produced under license in Indonesia as the "SP-1" series.

M14 rifle

_(7414626342).jpg.webp)

The M14 rifle, officially the United States Rifle, 7.62 mm, M14,[61] is an American selective fire automatic rifle that fires 7.62×51mm NATO (.308 Winchester) ammunition. The M14 rifle is basically an improved select-fire M1 Garand with a 20-round magazine.[62][63][64] The M14 rifle incorporated features of both the M1 rifle and the M1 Carbine, including the latter's short stroke piston design originally developed by Winchester Arms.

Ruger Mini-14

Designed by L. James Sullivan[65] and William B. Ruger, and produced by Sturm, Ruger & Co. the Mini-14 rifle employs an investment cast, heat-treated receiver and a version of the M1/M14 rifle locking mechanism.[66] Although the Mini-14 looks like the M14, it utilizes a reduced-size operating system, a different gas system and is chambered for the smaller .223 cartridge.[67]

Springfield Armory commercial production

In 1982, years after the closure of the U.S. Springfield Armory, a commercial firm – Springfield Armory, Inc. – began production of the M1 Rifle using a cast, heat-treated receiver with serial numbers in the 7,000,000+ range, along with commercially produced barrels (marked Geneseo, IL) and G.I. military surplus parts.[68]

Civilian use

United States citizens meeting certain qualifications may purchase U.S. military surplus M1 rifles through the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP). The CMP is run by the Corporation for the Promotion of Rifle Practice and Firearms Safety (CPRPFS), a not-for-profit corporation chartered by the United States Congress in 1996 to instruct citizens in marksmanship and promote practice and safety in the use of firearms.[69] The group holds a congressional charter under Title 36 of the United States Code. From 1903 to 1996, the CMP was sponsored by the Office of the Director of Civilian Marksmanship (DCM), a position first within the Department of War and later in the Department of the Army. The DCM was normally an active-duty Army colonel.

In 2009, an effort by the South Korean government to export about 850,000 firearms to the United States, including 87,000 M1 rifles, for eventual sale to civilians, was initially approved by the Obama administration, but it later blocked the sale in March 2010.[70] A State Department spokesman said the administration's decision was based on concerns that the guns could fall into the wrong hands and be used for criminal activity.[70] However, in January 2012, the U.S. and South Korea agreed on the sale of 87,000 M1 Garand rifles, and the South Korean government entered into discussion with U.S. civilian arms dealers.[71] Korea has sold tens of thousands of M1 Garand rifles to the U.S. civilian market between 1986 and 1994.[71] In 2018, the CMP reported they had received a shipment of more than 90,000 M1 Garand rifles from the Philippine and also stated plans to restore many of those rifles for civilian sale.

In August 2013, the Obama administration banned future private importation of all U.S. made weapons, including the M1 Garand.[72] This action did not preclude the return of surplus U.S. weapons, including M1 Garands, previously loaned by the U.S. to friendly nations, to the custody of the U.S. Government; in recent years, the CMP has received most of its surplus weapons through such returns from foreign countries. However, all civilian and military firearms imported into the U.S. after January 30, 2002, are required by federal law to have the name of the importer conspicuously stamped on the barrel, slide, or receiver of each weapon.[73] This requirement significantly lowers a military weapon's value relative to those without the importation markings as they distract from its original state.[74]

Military surplus Garands and post-war copies made for the civilian market are popular among enthusiasts. In 2015, John F. Kennedy's personal M1 Garand was auctioned by Rock Island Auction Company and sold for $149,500.[75] This rifle was acquired by Kennedy in 1959 from the Director of Civilian Marksmanship and has the serial number 6086970.[76]

Users

.jpg.webp)

Algeria[77]

Algeria[77] Argentina: Received about 30,000 M1s from the U.S. government before 1964. Some were converted to accept Beretta BM 59 magazines in the 1960s.[78]

Argentina: Received about 30,000 M1s from the U.S. government before 1964. Some were converted to accept Beretta BM 59 magazines in the 1960s.[78].svg.png.webp) Belgium: Used as a ceremonial rifle by the Belgian Police[79]

Belgium: Used as a ceremonial rifle by the Belgian Police[79] Brazil: Received large numbers of M1s from the U.S. government in the early 1950s. Some were converted to the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge and modified to accept FN FAL magazines.[78]

Brazil: Received large numbers of M1s from the U.S. government in the early 1950s. Some were converted to the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge and modified to accept FN FAL magazines.[78] Cambodia: Royal forces received M1 rifles from the U.S. during their civil war against communist insurgents.[80]

Cambodia: Royal forces received M1 rifles from the U.S. during their civil war against communist insurgents.[80].svg.png.webp) Canada: A small, but unknown, number of M1, M1C (with infra-red night vision equipment) and M1D rifles were owned by Canada. There were enough to equip a brigade and Garands were issued to certain Canadian Army units near the end of World War II and to some army and Royal Canadian Air Force personnel into the 1950s.[81]

Canada: A small, but unknown, number of M1, M1C (with infra-red night vision equipment) and M1D rifles were owned by Canada. There were enough to equip a brigade and Garands were issued to certain Canadian Army units near the end of World War II and to some army and Royal Canadian Air Force personnel into the 1950s.[81] Chile[82]

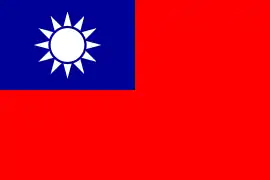

Chile[82] Republic of China (Taiwan): Supplied by the United States during WWII, Chinese Civil War, and later. Currently, the M1 Garand is the main rifle of the ROC honor guard.

Republic of China (Taiwan): Supplied by the United States during WWII, Chinese Civil War, and later. Currently, the M1 Garand is the main rifle of the ROC honor guard. People's Republic of China[83] Captured from Nationalist forces during the Chinese Civil War and US/ROK forces in the Korean War.

People's Republic of China[83] Captured from Nationalist forces during the Chinese Civil War and US/ROK forces in the Korean War. Cuba:[3] 10,000 ex-British M1s.[84]

Cuba:[3] 10,000 ex-British M1s.[84] Denmark: Received 69,810 M1 rifles (designated "Gevær m/50") from the U.S. government prior to 1964. Some were converted to the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge.[85] Also purchased 20,000 M1s from Italy.[86] The rifle has now been phased out of service.

Denmark: Received 69,810 M1 rifles (designated "Gevær m/50") from the U.S. government prior to 1964. Some were converted to the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge.[85] Also purchased 20,000 M1s from Italy.[86] The rifle has now been phased out of service. El Salvador: Received more than 1,365 M1s from the U.S. government until 1965 and 211 M1D sniper rifles.[87]

El Salvador: Received more than 1,365 M1s from the U.S. government until 1965 and 211 M1D sniper rifles.[87].svg.png.webp) Ethiopia: Received 20,700 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in the 1960s.[85]

Ethiopia: Received 20,700 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in the 1960s.[85].svg.png.webp) France: Used by the Foreign Legion and Free French Forces.[88][89] France also received 232,500 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1964.[85] The M1 was known as the Fusil semi-automatique 7 mm 62 (C. 30) M. 1[90] (Semi-automatic rifle 7.62mm (calibre .30) M1)

France: Used by the Foreign Legion and Free French Forces.[88][89] France also received 232,500 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1964.[85] The M1 was known as the Fusil semi-automatique 7 mm 62 (C. 30) M. 1[90] (Semi-automatic rifle 7.62mm (calibre .30) M1).svg.png.webp) Germany: Captured from United States Army, limited use in World War II.[91] German designation was 7.62 mm Selbstladegewehr 251 (a)[92]

Germany: Captured from United States Army, limited use in World War II.[91] German designation was 7.62 mm Selbstladegewehr 251 (a)[92] West Germany: Received 46,750 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1965.[85]

West Germany: Received 46,750 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1965.[85] Greece: Received 186,090 M1 and 1880 M1C/M1D rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] Still in use for ceremonial duties by the Presidential Guard.

Greece: Received 186,090 M1 and 1880 M1C/M1D rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] Still in use for ceremonial duties by the Presidential Guard. Indonesia: Received between 55,000 and 78,000 M1s and a minor number of M1Cs from the U.S. government prior to 1971; some rifles also supplied from Italy.[78]

Indonesia: Received between 55,000 and 78,000 M1s and a minor number of M1Cs from the U.S. government prior to 1971; some rifles also supplied from Italy.[78] Iran: Received 165,490 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1964.[85]

Iran: Received 165,490 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1964.[85] Israel: Received up to 60,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85]

Israel: Received up to 60,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] Italy: Used by the army from 1945. Beretta license-built 100,000 M1s from 1950 until the adoption of the BM59 in 1959.[86] Also received 232,000 M1s from the U.S. government between 1950 and 1970.[78] The M1 Garand was known in the Italian Army as the Fucile «Garand» M1 cal. 7,62.[93]

Italy: Used by the army from 1945. Beretta license-built 100,000 M1s from 1950 until the adoption of the BM59 in 1959.[86] Also received 232,000 M1s from the U.S. government between 1950 and 1970.[78] The M1 Garand was known in the Italian Army as the Fucile «Garand» M1 cal. 7,62.[93] Ivory Coast[94]

Ivory Coast[94].svg.png.webp) Japan: Issued to the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[95] Still used by the JSDF as a ceremonial weapon.[96]

Japan: Issued to the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[95] Still used by the JSDF as a ceremonial weapon.[96] Jordan: Received an estimated 25,000-30,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1974.[85]

Jordan: Received an estimated 25,000-30,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1974.[85] North Korea: Captured from South Korea in Korean War

North Korea: Captured from South Korea in Korean War South Korea: Received 296,450 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1950~1953/1964–1974.[85] Most of the M1 rifles were scrapped or sold back to the U.S. for civilian use.[97] Only very small numbers are used for reserve force and ceremonial duties.

South Korea: Received 296,450 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1950~1953/1964–1974.[85] Most of the M1 rifles were scrapped or sold back to the U.S. for civilian use.[97] Only very small numbers are used for reserve force and ceremonial duties..svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Laos: Received 36,270 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1975.[85]

Kingdom of Laos: Received 36,270 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1975.[85] Liberia[98]

Liberia[98] Netherlands: known as Geweer Garand 7,62mm in the Dutch Army and Geweer v/7,62 mm no. 2 S/aut in the Dutch Navy.[99]

Netherlands: known as Geweer Garand 7,62mm in the Dutch Army and Geweer v/7,62 mm no. 2 S/aut in the Dutch Navy.[99] Nicaragua[100]

Nicaragua[100] Norway: Received 72,800 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1964.[85] Still used by the drill team of the Hans Majestet Kongens Garde.

Norway: Received 72,800 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1964.[85] Still used by the drill team of the Hans Majestet Kongens Garde. Pakistan: Received possibly 150,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85]

Pakistan: Received possibly 150,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] Panama[101]

Panama[101] Paraguay: Received 30,750 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85]

Paraguay: Received 30,750 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] Portugal : Received 80,000 M1 rifles from the US between 1950 and 1966, used to equip frontline Infantry battalions till 1966 (non infantry units continued to use bolt-action rifles), when it was replaced by variants of the FN FAL in infantry units. After 1966 it was used to equip all Armed Police/Police units and Non-Infantry units in Portugal, while in 1970, it was phased out of Police & Non-Infantry use in Mozambique and Angola, where the FN FAL was introduced in Police units. M1 continued to be the service issue rifle for all Police in Mainland Portugal/Metropolitan Portugal well into the 1980s when they were scrapped.

Portugal : Received 80,000 M1 rifles from the US between 1950 and 1966, used to equip frontline Infantry battalions till 1966 (non infantry units continued to use bolt-action rifles), when it was replaced by variants of the FN FAL in infantry units. After 1966 it was used to equip all Armed Police/Police units and Non-Infantry units in Portugal, while in 1970, it was phased out of Police & Non-Infantry use in Mozambique and Angola, where the FN FAL was introduced in Police units. M1 continued to be the service issue rifle for all Police in Mainland Portugal/Metropolitan Portugal well into the 1980s when they were scrapped. Philippines: Received 34,300 M1 and 2630 M1D rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1975. Retired from active Philippine Marine Corps service.[102][103] Used by units of the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit.[104] In 2017, it was reported that the Philippine government may send 86,000 rifles to the U.S. Civilian Marksmanship Program.[105]

Philippines: Received 34,300 M1 and 2630 M1D rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1975. Retired from active Philippine Marine Corps service.[102][103] Used by units of the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit.[104] In 2017, it was reported that the Philippine government may send 86,000 rifles to the U.S. Civilian Marksmanship Program.[105] Saudi Arabia: Received 34,530 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85]

Saudi Arabia: Received 34,530 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] Thailand: Received about 40,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1965.[85]

Thailand: Received about 40,000 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1965.[85] Turkey: Received 312,430 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1953–1970,[85] saw action in Korean War[106] and 1974 Cyprus War.[107][108] Still used by the Turkish Armed Forces as a ceremonial weapon.[109][110][111]

Turkey: Received 312,430 M1 rifles from the U.S. government in 1953–1970,[85] saw action in Korean War[106] and 1974 Cyprus War.[107][108] Still used by the Turkish Armed Forces as a ceremonial weapon.[109][110][111] United Kingdom: Received 38,000 as Lend-Lease[84]

United Kingdom: Received 38,000 as Lend-Lease[84] United States: Standard issue rifle for U.S. Army and Marine Corps Infantry from 1936 to 1957.[112] Used in the 1970s in reserve and rear-echelon capacities. Still in use for official military ceremonies, ROTC units, and Civil Air Patrol. Additionally, it remains the standard rifle of the United States Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon.

United States: Standard issue rifle for U.S. Army and Marine Corps Infantry from 1936 to 1957.[112] Used in the 1970s in reserve and rear-echelon capacities. Still in use for official military ceremonies, ROTC units, and Civil Air Patrol. Additionally, it remains the standard rifle of the United States Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon. Uruguay[101]

Uruguay[101] Venezuela: Received 55,670 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85]

Venezuela: Received 55,670 M1 rifles from the U.S. government prior to 1975.[85] South Vietnam: Received 220,300 M1 and 520 M1C/M1D rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1975.[85]

South Vietnam: Received 220,300 M1 and 520 M1C/M1D rifles from the U.S. government in 1950–1975.[85].svg.png.webp) North Vietnam and

North Vietnam and  Vietnam: (Largely captured and/or inherited from now-defunct Army of the Republic of Vietnam) Some used by the Viet Cong and the Viet Minh, taken from American, French and South Vietnamese forces/armories[113] with a few modified to make them compact.

Vietnam: (Largely captured and/or inherited from now-defunct Army of the Republic of Vietnam) Some used by the Viet Cong and the Viet Minh, taken from American, French and South Vietnamese forces/armories[113] with a few modified to make them compact.

Non-state actors

See also

- M1 carbine

- Garand carbine – another John Garand-designed weapon

- Gewehr 43

- List of U.S. Army weapons by supply catalog designation SNL B-21

- SVT-40

- Table of handgun and rifle cartridges

Notes

- Officially designated as U.S. rifle, caliber .30, M1, later simply called Rifle, Caliber .30, M1, also called US Rifle, Cal. .30, M1

- Additional trials in 1930 found Bostonian Joseph White's rifles insufficiently robust.[21]

References

- Thompson, Leroy (February 20, 2013). The M1903 Springfield Rifle. Weapon 23. Osprey Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 9781780960111.

- "L'armement français en A.F.N." Gazette des Armes (in French). No. 220. March 1992. pp. 12–16.

- McNab, Chris (2002). 20th Century Military Uniforms (2nd ed.). Kent: Grange Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-84013-476-6.

- de Quesada, Alejandro (January 10, 2009). The Bay of Pigs: Cuba 1961. Elite 166. Osprey Publishing. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-1-84603-323-0.

- Laffin, John (June 15, 1982). Arab Armies of the Middle East Wars 1948–73. Men-at-Arms 128. Osprey Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-85045-451-2.

- Katz, Sam (March 24, 1988). Arab Armies of the Middle East Wars (2). Men-at-Arms 128. Osprey Publishing. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-85045-800-8.

- Taylor, Peter (1997). Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84908-621-9.

- Ball, Bill (June 2004). "The Beretta "Type E" Garand, Variations on John Garand's Combat Proven M1" (PDF). The Small Arms Review. Vol. 7 no. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 27, 2011.

- Thompson, Leroy (2012). The M1 Garand. Oxford: Osprey. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-84908-621-9.

- "U.S. Department of the Army Technical Manual No. 9-1005-222-12" (PDF). March 17, 1969. p. 13. Retrieved May 18, 2007 – via Biggerhammer.net.

- Hogg, Ian V.; Weeks, John (1977). "US Rifle, Caliber .30in ('Garand'), M1-M1E9, MiC, M1D, T26". Military Small-Arms of the 20th Century (2nd ed.). London: Arms & Armour Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-88254-436-6.

- "The Best Battle Implement Ever Devised". Springfield Armory. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Pendergast, Sara; Pendergast, Tom (2000). "Firearms". St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. St. James Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-55862-405-4.

- Seijas, Bob. "History of the M1 Garand Rifle". Garand Collectors Association. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Canfield, Bruce (April 28, 2016). "The M14 Rifle: John Garand's Final Legacy". American Rifleman. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Hatcher, Julian (1983) [1948]. Book of the Garand (Reprint ed.). Highland Park, NJ: Gun Room Press. ISBN 0-88227-014-1.

- "John Cantius Garand and the M1 Rifle". Springfield Armory. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- Walter, John (2006). Rifles of the World (3rd ed.). Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Fitzsimons, op. cit., Volume 19, p. 2092, "Pedersen", describes the ammunition as "lubricated".

- Hatcher, Julian S. (1947). Hatcher's Notebook. Harrisburg, PA: Military Service Publishing Co. pp. 44–46, 155–156, 165–166.

- Walter, John (2006). Rifles of the World (3rd ed.). Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1977). "Garand". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Weapons and Warfare. 10. London: Phoebus. p. 1088.

- "Military Firearms: M1 Garand Rifle". Olive-Drab.com. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- Canfield, Bruce N. (September 2011). "The First Garands". American Rifleman. pp. 68–75 & 93.

- Brown, Jerold E. (2000). Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Army. Greenwood Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-313-29322-1.

- Hogg, Ian V.; Weeks, John S. (February 10, 2000). Military Small Arms of the 20th Century (7th ed.). Krause Publications. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-87341-824-9.

- Bishop, Chris (1998). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. New York: Orbis Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7607-1022-7.

- "Department of the Army Appropriations for 1954: Hearings, 83rd Congress, 1st Session". Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. 1953: 1667. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Canfield, Bruce N. (November 2015). "Cold War Warrior". American Rifleman. pp. 54–99.

- "Prints and Posters: The American Soldier, 1966 - by H. Charles McBarron". Center of Military History.

- "M1 Garand Captured in Afghanistan". CMP Forums. June 4, 2014.

- Popenker, Max. "Modern Firearms: Rifle M1 Garand". WorldGuns.ru. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- Departments of the Army and the Air Force (October 1951). U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1 (PDF). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office – via Easy39th.com.

- Mangrum, Jamie (2004). "M1 Garand Operations: Loading and Unloading". SurplusRifle.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- "Field Stripping the M1 Garand". Civilian Marksmanship Program. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2006). U.S. Marine Rifleman 1939–45: Pacific Theater. Osprey Publishing. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1-84176-972-1.

- Karwan, Charles (October 2002). "History in your hands: Springfield Armory's new M1 Garand: the most significant rifle of the 20th Century is once again available to the American shooter". Guns. p. 44.

- "Springfield Armory M1 Garand Operating Manual" (PDF). Springfield Armory. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 9, 2006. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- "FM 23-5". Department of the Army. 1965. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- "FM 23-100", Department of the Army (1943)

- George, John B. (1948). Shots Fired In Anger. The Samworth Press. ISBN 0-935998-42-X.

- Dunlap, Roy F. (1948). Ordnance Went Up Front. The Samworth Press. ISBN 978-1-884849-09-1.

- Bishop, Chris (2002). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. Sterling Publishing. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-58663-762-0.

- CW5 Charles D. Petrie, U.S. Army (April 2012). "More On The "Ping"". American Rifleman: 42.

- Canfield, Bruce (1998). The Complete Guide to the M1 Garand and the M1 Carbine. Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray Publishers. pp. 69–70. ISBN 0-917218-83-3.

- Bishop, Chris (2002). The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II. Sterling Publishing. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-58663-762-0.

- "Fitting the Army's Modern Garand Rifle". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. March 1944. p. 74.

- Henry, Mark R. (2000). The U.S. Army in World War II: The Pacific (Illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-85532-995-9.

- "M1 Accessories - Winter Trigger". Civilian Marksmanship Program. 2002.

- Ewing, Mel. "Sniper Central: U.S. Army M1C & M1D". SniperCentral.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- Canfield, Bruce N. (September 2014). "Better Late Than Never". American Rifleman. 162: 81–85.

- Hutchison, Kevin D. (1994). World War II in the North Pacific: Chronology and Fact Book. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 247.

Col. Alexander had served as General Buckner's naval liaison officer, and was appointed to the Pacific Warfare Board following the General's death on Okinawa in June 1945

- Weeks, John (1979). World War II Small Arms. New York: Galahad Books. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0-88365-403-2.

- "Fact Sheet #5: The M1 'Tanker' Modification". Springfield Armory.

- Walter, John (2006). Rifles of the World. Krause Publications. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Duff, Scott A. (1996). The M1 Garand, World War II: History of Development and Production, 1900 Through 2 September 1945. Scott A. Duff Publications. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-888722-01-7.

As a major, Alexander had been a proponent of the 18" 'Tanker' Garand ever since testing his own ordnance-modified version on Noemfoor Island, New Guinea

- Thompson 2012, p. 38.

- Rayle, Roy E. (2008). Random Shots: Episodes In The Life Of A Weapons Developer. Bennington, VT: Merriam Press. pp. 17–22, 95–95. ISBN 978-1-4357-5021-0.

- ""Japanese Garand" WWII Semi-Automatic Rifle". The National Firearms Museum. NRA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Walter, John (2006). Rifles of the World (3rd ed.). Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Direct Support and General Support Maintenance Manual, Including Repair Parts and Special Tools Lists, (Including Depot Maintenance, Repair Parts and Special Tools), Rifle, 7.62-MM, M14, W/E(1005- 589-1271), Rifle, 7.62-MM, M14A1, W/E(1005-072- 5011), Bipod, Rifle, M2(1005-711-6202). Washington, DC: Department of the Army. August 1972.

- Bruce, Robert (April 2002). "M14 vs. M16 in Vietnam". Small Arms Review. Vol. 5 no. 7.

- "M14". Jane's International Defense Review. Jane's Information Group. 36: 43. 2003.

The M14 is basically an improved M1 with a modified gas system and detachable 20-round magazine.

- "M14 7.62mm Rifle". Global Security. July 7, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- Ezell, Virginia Hart (November 2001). "Focus on Basics, Urges Small Arms Designer". National Defense. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006.

- Guthrie, J. "The Mini Grows Up—Again". Rifle Shooter. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010.

- "Ruger Mini 14 Autoloader". Sturm, Ruger & Co. Archived from the original on September 21, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- "GI's Best Friend Now In Limited Production As Collectors Item From Springfield Armory" (Press release). Springfield Armory Inc. November 30, 2001.

- Pub.L. 104–106 (text) (pdf), 36 Stat. 5502, enacted February 10, 1996

- "Obama Administration Reverses Course, Forbids Sale of 850,000 Antique Rifles". Fox News. September 1, 2010.

- "정부, M1소총 8만7000여정 수출 추진…美 정부 동의" [Government promotes export of 87,000 M1 rifles...U.S. Government Consents]. The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). January 19, 2012.

- Lederman, Josh (August 29, 2013). "Obama Offers New Executive Actions On Gun Control". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016.

- ATF Guidebook - Importation & Verification of Firearms, Ammunition, and Implements of War. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 2001.

- Ankony, Robert C. (April 2000). "The Financial Assessment of Military Small Arms". Small Arms Review. pp. 53–59 – via robertankony.net.

- "Lot 1807: Springfield Armory National Match 1959 M1 Garand John F. Kennedy". Rock Island Auction. September 11, 2015.

- "JFK's M1 Garand". Civilian Marksmanship Program Forum. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- Windrow, Martin (1997). The Algerian War, 1954–62. Men-at Arms 312. London: Osprey Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-85532-658-3.

- Walter, John (2006). Rifles of the World (3rd ed.). Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Small Arms Survey (2015). "Half a Billion and Still Counting: Global Firearms Stockpiles" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2011: Profiling the Problem. Oxford University Press. p. 69.

- Wille, Christina (June 2006). "How Many Weapons Are There in Cambodia?". Small Arms Survey. p. 18. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Canadian Army EME Manuals; photographic evidence; book Without Warning by Clive Law.

- Smith, Joseph E. (1969). Small Arms of the World (11 ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Stackpole Company. p. 292.

- Thompson 2012, p. 74.

- Thompson 2012, p. 59.

- Walter, John (2006). Rifles of the World (3rd ed.). Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-89689-241-5.

- Ball, Willis (2002). "Beretta's BM 59, The Ultimate Garand" (PDF). Guns. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- Montes, Julio A. (May 2000). "Infantry Weapons of the Salvadoran Forces". Small Arms Review. Vol. 3 no. 8.

- Jordon, David (2005). The History of the French Foreign Legion: From 1831 to Present Day. The Lyons Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-59228-768-0.

- Sumner, Ian (1998). The French Army 1939-45. Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-85532-707-8.

- Manuel du Grade TTA 116 (in French). Berger-Levrault. March 19, 1956. p. 226.

- Thompson 2012, p. 44.

- Hand weapons: a reference work about the prey weapons of the Wehrmacht (1942) (PDF) (in German). Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek. 2008. ISBN 978-3-8370-4042-5.

- Armi e mezzi in dotazione all'esercito [Arms and means supplied to the army] (in Italian). Roma: Ministero Della Difesa. 1955.

- de Tessières, Savannah (April 2012). Enquête nationale sur les armes légères et de petit calibre en Côte d'Ivoire: les défis du contrôle des armes et de la lutte contre la violence armée avant la crise post-électorale (PDF) (Report). Special Report No. 14 (in French). UNDP, Commission Nationale de Lutte contre la Prolifération et la Circulation Illicite des Armes Légères et de Petit Calibre and Small Arms Survey. p. 74.

- Smith 1969, p. 494.

- 陸上自衛隊パーフェクトガイド2008–2009. Gakken. 2008. p. 195. ISBN 978-4-05-605141-4.

- Thompson 2012, p. 67.

- Doe, Samuel Kanyon; Enahoro, Peter (1985). Doe, the Man Behind the Image. publisher not identified.

- Scarlata, Paul (April 2014). "Military rifle cartridges of the Netherlands: from Sumatra to Afghanistan". Shotgun News.

- Jurado, Carlos Caballero (1990). Central American Wars 1959–89. Men-at-Arms 221. London: Osprey Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-85045-945-6.

- Gander, Terry J.; Hogg, Ian V., eds. (May 1995). Jane's Infantry Weapons 1995/1996 (21st ed.). Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-1241-0.

- Martir, Jonathan (November 2001). "Scout Sniper Development - "An accurate shot to the future"". CITEMAR6. Philippine Marine Corps. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- "The incumbent Director of Government Arsenal". Arsenal.mil.ph. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- "Philippine CAFGU". Photobucket.com. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Breaking: Civilian Marksmanship Program May Receive 86,000 M1 Garand Rifles from the Philippines". The Firearm Blog. April 7, 2017.

- "Turkish Army in Korean War". Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- "Cyprus: Round Two". Newsweek. August 23, 1974. Archived from the original (Photo) on February 5, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Temmuz 1974: Kıbrıs Barış Harekatı" [July 1974: Cyprus Peace Operation]. Imageshack. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- "Turkish Military High School ceremonial procession". Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality.

- "Deniz Harp Okulu'nda tören" [Ceremony at the Turkish Naval Academy]. Deniz Harp Okulu. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "Turkish Air Force guard at Anitkabir". Bernard Gagnon.

- Thompson 2012, p. 4.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (February 10, 2009). North Vietnamese Army Soldier 1958–75. Warrior 135. Osprey Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9781846033711.

- "A Persian take on the M1". The Firearm Blog. October 27, 2016.

- Shea, Dan (March 2007). "Improvised Weapons of the Irish Underground (Ulster)". Small Arms Review. Vol. 10 no. 6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to M1 Garand. |

- Canfield, Bruce (December 23, 2013). "7.62x51mm NATO U.S. Navy Garand Rifles". American Rifleman.

- FM 23-5 Basic Field Manual U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1 (PDF). Washington, DC: United States War Department. 1940. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016.

- Departments of the Army and the Air Force (October 1951). Field Manual, U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1 (PDF). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- "List of M1 Garand Serial Numbers By Month and Year". Fulton Armory.

- "How to Shoot the U.S. Army Rifle (1943)" at the Internet Archive

- "M1 Garand History". Springfield Armory.

- "He Invented the World's Deadliest Rifle". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. December 1940. p. 68.

- "Collection Record: U.S. Rifle M1 .30 SN# 1". Springfield Armory Museum.

- "The Garand Collectors Association (GCA)". – United States Association, with members worldwide, dedicated to the research and documentation of the M1 Garand.

- The short film "Rifle Marksmanship with the M1 Rifle (1942)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film "Rifle - U.S. Cal. .30 M1 - Principles of Operation (1943)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive