Macginitiea

Macginitiea is an extinct genus in the sycamore or plane tree family ranging from the Late Paleocene to Late Eocene of North America, prominently known from the Clarno Formation of central Oregon.[1][2] The genus is strictly used to describe leaves, but has been found in close association with other fossil platanoid organs, which collectively have been used for whole plant reconstructions.[2][3] Macginitiea and its associated organs are important as together they comprise one of the most well-documented and ubiquitous fossil plants, particularly in the Paleogene of North America.[4][5]

| Macginitiea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Macginitiea gracilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Platanaceae |

| Genus: | †Macginitiea Wolfe & Wehr (1987) |

| Type species | |

| Macginitiea gracilis | |

| Species | |

| |

Because paleobotanical material is often found in disarticulation, different species names are often used to refer to different organs (e.g. leaves, fruits, wood) even if those organs might have belonged to the same plant. When these organ species are considered together as a whole plant, the study is known as a whole plant reconstruction. Some localities have enough co-occurrences of different fossil plant organs that whole plant reconstructions are possible, one example being the Cercidiphyllum-like Joffrea from the Joffre Bridge locality of Alberta, Canada.[6]

The earliest definite occurrences of Macginitiea have been observed from the Comstock Flora of southern Willamette Valley, Oregon, which has been dated to be younger than 38-40 million years old (Bartonian), though similar ages are observed throughout the Pacific Northwest, with occurrences around 38-39 Ma.[4]

Description

Macginitiea leaves are readily recognizable by their three to nine, equally spaced, palmate lobes.[2][7] Like other Platanaceae, Macginitiea has palinactinodromous primary venation, a type of venation wherein primary veins fork multiple times. Macginitiea also has an inflated petiole base,[2] which in modern counterparts encloses the underlying axillary buds for the next year, indicating their deciduous nature.[8] The branching of primary veins often occurs basally, rather than suprabasally (as encountered in some modern species).[2] Although the secondary veins of modern Platanus are usually straight, the secondary veins of Macginitiea are so regular and prominent compared to other platanoids that this recognizable “chevron” pattern has been considered a primary characteristic of the species.[2][3][7][9] Margins are usually entire in all Macginitiea species, but can sometimes have minor teeth.[3]

Macginitiea differs from modern Platanus with its often greater number of lobes and narrower angle between adjacent primary veins.[7]

Different species of Macginitiea can be distinguished on the bases of lobe depth, extent of chevrons, prevalence of teeth, and partly lobe number.[3] In total, 5 species of Macginitiea leaves have been described.[2][3][5][7]

| Macginitiea Species | Age & Locality | Number of Lobes | Depth of Sinuses | Primary Venation, Angle Between Adjacent Primary Veins | Extent of Chevron Secondaries | Marginal Teeth |

| M. nobilis | Paleocene Alberta, Canada | 3 | around 30% | Basally actinodromous, 30-35° | Present in basal portion of the leaf | At the end of each secondary vein |

| M. gracilis | Eocene Republic Washington, Western U.S. | 5 | - | Palinactinodromous, 15-30° | Entire leaf | Absent |

| M. angustiloba | Eocene Clarno Formation, Oregon | 5-9 (5-7) | 40-68% | Basally palinactinodromous | Entire leaf | Rarely |

| M. wyomingensis | Middle Eocene Green River Formation, Western U.S. | 5 | around 36% | Palinactinodromous, 15-30° | Entire leaf | Present, Prominent |

| M. whitneyi | Early Eocene Chalk Bluffs, California | 5-7 (7-9) | very shallow, 25-35% | Palinactinodromous, 15-30° | Entire leaf | Absent |

Table adapted from Pigg & Stockey (1991).[3]

Whole plant reconstructions

The Clarno Plane

The “Clarno Plane” was established as an informal name to refer to the whole plant recognized from five fossil species: Macginitiea angustiloba (leaves), Plataninium haydenii (wood), Macginicarpa glabra (infructescences), Platananthus synandrus (staminate inflorescences), and Macginistemon mikanoides (isolated stamen clusters).[2] The Clarno Plane is known from the west coast of North America across several states, including central California, Oregon, and northern Washington.[2][4]

Like the modern Platanus, Macginicarpa has clusters of five carpels per floret. However, in striking contrast to the modern, Macginicarpa flowers have a well-developed perianth and fruits lack the prominent dispersal hairs characteristic of the modern Platanus. Modern carpel numbers are more variable than the consistent five of Macginicarpa, ranging from four to nine.[2][8]

Staminate flowers (Platananthus synandrus) have an even more developed perianth than pistillate flowers, but similarly have more consistent numbers of parts than the modern, with 5 stamens per floret.[2] P. synandrus pollen appears to be smaller than pollen from modern Platanus. Platananthus synandrus is also distinctive from extant Platanus for the elongation of its connectives, extensions of filament tissue that cover or divide an anther. In Platananthus and in modern Platanus, peltate (shield-like) connectives cover the tops of anthers, but the connectives of Platananthus are 4 to 5 times the length of the modern. Stamens are connate (fused) within each floret, causing them to be shed in clusters of stamen bundles, rather than one at a time as in modern Platanus species. Stamen bundles associated with Macginitiea have been put under the genus Macginistemon.[2]

Plataninium wood is similar, but has wider rays and more scalariform (ladder-like) perforations than that of recent species.[2]

As of 1986, Dr. Steven Manchester said that “The Clarno Plane is currently the most completely documented fossil angiosperm species, known morphologically and anatomically from wood, leaves, pistillate and staminate inflorescences, fruits, and pollen.”[2] Associations of multiple organs of the Clarno Plane in various combinations have been found in “more than ten localities” throughout western North America, as of 2008.[5] Other platanoid leaves have since been found in association with reproductive structures, including leaves such as Platimeliphyllum, Ettingshausenia, Evaphyllum, Platanus neptuni, Platanus nobilis, and Sapindopsis.[5]

The Joffre Plane

The Paleocene fossil leaf species Platanus nobilis was established as a species intermediate between Macginitiea and modern Platanus.[3] However, differences between P. nobilis and Macginitiea were later considered too minor to justify placing P. nobilis in a different genus, particularly since P. nobilis was associated with Macginicarpa inflorescences.[5][7] As such, P. nobilis was reassigned to Macginitiea nobilis.[7]

The “Joffre Plane” as a whole plant reconstruction includes leaves from Macginitiea nobilis, pistillate inflorescences and infructescences from Macginicarpa manchesteri, and staminate inflorescences of Platananthus speirsae.[3] Macginitiea nobilis is set apart from other Macginitiea species by its fewer number of lobes (usually 3, instead of 5-9) and less distinct “chevron” venation pattern. M. nobilis has been found in various stages of development from the Joffre Bridge locality, from seedlings with cotyledonous leaves to mature, true, trilobate leaves.[3]

Discovery and naming

The genus Macginitiea was named after the prominent paleobotanist Harry Dunlap MacGinitie, who was the first person to suggest the close relationship of Macginitiea to the family Platanaceae.[9] Though fossils of Macginitiea were originally classified under the genus Aralia,[10] MacGinitie noticed that the venation patterns of Aralia angustiloba more closely resembled that of Platanus rather than Aralia, and reclassified Aralia angustiloba as Platanophyllum angustiloba.[2][9] However, Wolfe & Wehr found that the genus Platanophyllum was problematic, and therefore made the new genus Macginitiea for these leaves.[9]

Ecology

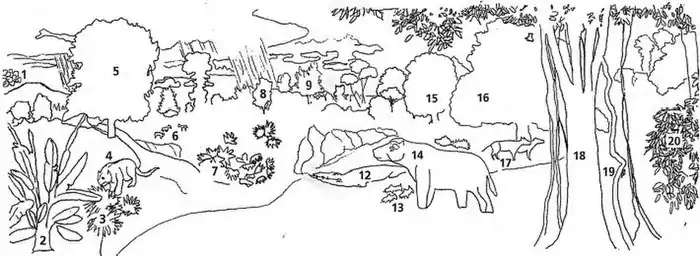

Macginitiea has been known to be the dominant element in many Eocene floras.[4] The Clarno Plane is thought to have occupied open, riparian habitats, similar to that of modern Platanus. They also have been found several times in co-occurrence with Cercidiphyllum-like plants. The association with Cercidiphyllum suggests that the Clarno Plane was tolerant of full sunlight and poorly developed soils.[4]

References

- Retallack, G.J. (1996). "Reconstructions of Eocene and Oligocene plants and animals of central Oregon". Oregon Geology. 58 (3): 51–59.

- Manchester, S. R. (1986). "Vegetative and reproductive morphology of an extinct plane tree (Platanaceae) from the Eocene of western North America". Botanical Gazette. 147 (2): 200–226. doi:10.1086/337587.

- Pigg, K. B.; Stockey, R. A. (1991). "Platanaceous plants from the Paleocene of Alberta, Canada". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 70 (1–2): 125–146. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(91)90082-e.

- Myers, J. A. (2003). Terrestrial Eocene-Oligocene Vegetation and Climate in the Pacific Northwest. From Greenhouse to Icehouse: The Marine Eocene-Oligocene Transition. Columbia University Press, New York, 171-185.

- Maslova, N. P. (2008). "Association of vegetative and reproductive organs of platanoids (Angiospermae): significance for systematics and phylogeny". Paleontological Journal. 42 (12): 1393–1404. doi:10.1134/s0031030108120034.

- Crane, P. R.; Stockey, R. A. (1985). "Growth and reproductive biology of Joffrea speirsii gen. et sp. nov., a Cercidiphyllum-like plant from the Late Paleocene of Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Botany. 63 (2): 340–364. doi:10.1139/b85-041.

- Wheeler, E. A.; Manchester, S. R. (2014). "Middle Eocene trees of the Clarno Petrified Forest, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon". PaleoBios. 30 (3).

- Nixon, K. C.; Poole, J. M. (2003). "Revision of the Mexican and Guatemalan species of Platanus (Platanaceae)". Lundellia. 6: 103–137.

- Wolfe, J. A., & Wehr, W. (1987). Middle Eocene dicotyledonous plants from Republic, northeastern Washington.

- Lesquereux, L. (1878). Report on the fossil plants of the auriferous gravel deposits of the Sierra Nevada. Welch, Bigelow.