Machairodus

Machairodus is a genus of large machairodontine saber-toothed cats that lived in Africa and Eurasia during the late Miocene. It is the animal from which the subfamily Machairodontinae gets its name and has since become a wastebasket taxon over the years as many genera of sabertooth cat have been and are still occasionally lumped into it.

| Machairodus | |

|---|---|

| |

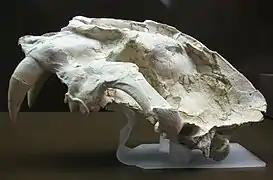

| M. aphanistus skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | †Machairodontinae |

| Tribe: | †Machairodontini |

| Genus: | †Machairodus Kaup, 1833 |

| Type species | |

| †Machairodus aphanistus Kaup, 1832 | |

| Species | |

Discovery

Machairodus was first named in 1832, by German Naturalist Johann Jakob Kaup. Though its remains were known since 1824, it was believed by Georges Cuvier that the fossils had come from a species of bear, which he called Ursus cultridens (known today as Megantereon) based on composite sample of teeth from different countries, species and geologic ages, leading to what would become a long series of complications. Kaup however, recognized the teeth as those of felids and promptly reclassified the existing specimens as Machairodus, including M. cultridens in it. The name quickly gained acceptance and by the end of the 19th Century, many species of felid or related feliform (such as nimravids) were lumped into the genus Machairodus, including but not limited to Sansanosmilus, Megantereon, Paramachairodus, Amphimachairodus, Nimravides, and Homotherium among others. This would eventually turn Machairodus into something of a wastebasket taxon, which would be rectified with the discoveries of more complete skeletons of other machairodonts.[2]

Description

In general Machairodus was similar in size to a modern lion or tiger, at 2 m (6.6 feet) long and standing about 1 m (3.3 feet) at the shoulder.

M. aphanistus from the Mediterranean late Miocene is known to be rather tiger-like in size and skeletal proportions, with a mass of 100 kg (220 pounds) to 240 kg (530 pounds). It was similar to the related Nimravides of North America. The skeleton also indicates that this species would have possessed good jumping abilities.[3]

M. alberdiae was contemporary with M. aphanistus in Cerro de los Batallones fossil deposits and was smaller and more primitive in anatomical features and would not have exceeded 100 kg (220 pounds).[4]

M. horribilis of China is the largest known species of the genus and is comparable in size to the much later Smilodon populator, weighing around 405 kg (893 pounds). Its skull, measuring upwards of 16 inches (41 cm) in length, is one of the largest known skulls for any machairodont, with only a recently described S. populator skull rivaling it in size, with the latter cat outweighing M. horribilis at 960 lb (440 kg).[5][6]

Overall, the skull of Machairodus was noticeably narrow compared with the skulls of extant pantherine cats, and the orbits were relatively small. The canines were long, thin and flattened from side to side but broad from front to back like the blade of a knife, as in Homotherium. The front and back edges of the canines were serrated when they first grew, but these serrations were worn down in the first few years of the animal's life. However, a skull of M. horribilis was shown to be similar to extant pantherines in some cranial characters, suggesting new evidence for the diversity of killing bites even within in the largest saber-toothed carnivorans, offering an additional mechanism for the mosaic evolution leading to functional and morphological diversity in sabertooth cats.[7]

Machairodus probably hunted as an ambush predator. Its legs were too short to sustain a long chase, so it most likely was a good jumper, and used its canines to cut open the throat of its prey. Its teeth were rooted to its mouth and were as delicate as those in some related genera, unlike most saber-toothed cats and nimravids of the time, which often had extremely long canines which hung out of their mouths. The fangs of Machairodus, however, were able to more easily fit in its mouth comfortably while being long and effective for hunting.[8] Despite its great size, the largest example of Machairodus, M. horribilis was better equipped to hunt relatively smaller prey than Smilodon, as evidenced by its moderate jaw gape of 70 degrees, similar to the gape of a modern lion.[5]

Classification

The fossil species assigned to the genus Machairodus were divided by Turner into two grades of evolutionary development, with M. aphanistus and the North American "Nimravides" catacopis representing the more primitive grade and M. coloradensis and M. giganteus representing the more derived grade.[9] The characteristics of the more advanced grade include a relative elongation of the forearm and a shortening of the lumbar region of the spine to resemble that in living pantherine cats.[9] Subsequently, the more derived forms were assigned a new genus, Amphimachairodus, which includes M. coloradensis, M. kurteni, M. kabir and M. giganteus.[1] In addition, M. catacopsis was reclassified as N. catacopsis.[10]

Paleobiology

Studies of Machairodus indicate that the cat relied predominantly on its neck muscles to make the killing bite applied to its victims. The cervical vertebrae show clear adaptations to making vertical motions in the neck and skull. There are also clear adaptations for precise movements, strength, and flexibility in the neck that show compatibility with the canine-shearing bite technique that machairodontine cats are believed to have performed. These adaptations are believed to have also been partial compensation in this primitive machairodont against the high percentage of canine breakages seen in the genus.[11]

Paleoecology

Machairodus seemed to prefer open woodland habitat, as evidenced by finds at Cerro de los Batallones, which is of Vallesian age. As a top predator at Batallones, it would have hunted large herbivores of the time. Such herbivores would have included horses like Hipparion, the hornless rhinoceros Aceratherium, the giraffes Deccanatherium and Birgerbohlinia, the deer Euprox and Lucentia, the antelopes Paleoreas, Tragoportax, Miotragocerus and Dorcatherium, the gomphotherid mastodon Tetralophodon, the porcupine Hystrix, and the suid Microstonyx, . Machairodus would have competed for such prey with the Amphicyonid Magericyon, fellow machairodonts Promegantereon and Paramachairodus, bears such as Agriotherium and Indarctos, and the small hyaenid Protictitherium. While Agriotherium and Magericyon would likely have been strongly competitive with Machairodus for food, Promegantereon, Paramachairodus and Protictitherium likely were less potential rivals.[12] Evidence also exists indicating that Machairodus may have been prone to niche partitioning with Magericyon, possibly living in slightly different habitats, with the machairodont preferring more heavily vegetated habitats while the bear-dog hunted in the more open areas. Dietary preferences may also have played a role in the coexistence between these two large predators at Batallones.[13]

Based on its jaw gape, the largest species, M. horribilis was probably a hunter of relatively slow-moving horses.[14]

Pathology

Machairodus aphanistus fossils recovered from Batallones reveal a high percentage of tooth breakages, indicating that unlike later machairodonts, due to a lack of protruding incisors Machairodus often used its sabers to subdue prey in a manner similar to modern cats; this was a more risky strategy that virtually ensured that damage to their saber teeth often occurred.[15]

References

- Antón (2013).

- Antón (2013), pp. 118–119.

- Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and their fossil relatives. pp. 45. ISBN 9780231102292.

- Fernandez-Monescillo, Marcos; Anton, Mauricio; Salesa, Manuel.J (2017). "Alaeoecological implications of the sympatric distribution of two species ofMachairodus (Felidae, Machairodontinae, Homotherini) in the Late Miocene of Los Valles de Fuentidueña (Segovia, Spain)". Historical Biology. 31 (7): 903–913. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1402894.

- Switek, Brian (November 3, 2016). "The Biggest Saber Cat". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/14/science/saber-toothed-tiger.html?referringSource=articleShare

- Deng, Tao; Zhang, Yun-Xiang. "A skull of Machairodus horribilis and new evidence for gigantism as a mode of mosaic evolution in machairodonts (Felidae, Carnivora)". Vertebrata Palasiatica. 54: 302–318 – via ResearchGate.

- Legendre, S.; Roth, C. (1988). "Correlation of carnassial tooth size and body weight in recent carnivores (Mammalia)". Historical Biology. 1 (1): 85–98. doi:10.1080/08912968809386468.

- Turner, Alan (1997). The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives. Illustrated by Mauricio Antón. Columbia University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-231-10228-5.

- Antón, Mauricio; Salesa, Manuel J.; Siliceo, Gema (2013). "Machairodont adaptations and affinities of the Holarctic late Miocene homotherin Machairodus(Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae): the case of Machairodus catocopis Cope, 1887". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (5): 1202–1213. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.760468. hdl:10261/93630. ISSN 0272-4634.

- https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article-abstract/188/1/319/5581941?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Antón (2013), p. 52.

- Switek, Brian (November 30, 2012). "Carnivorous Neighbors — How Sabercats and a Bear Dog Managed to Coexist". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Weisberger, Mindy (November 7, 2016). "Saber-Toothed Cat Had a Huge Skull, But a Puny Bite". Live Science. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Antón (2013), pp. 183–184.

- Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. ISBN 9780253010421.