Mackerel

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

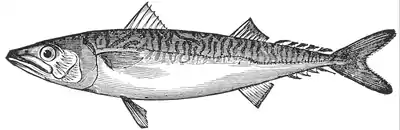

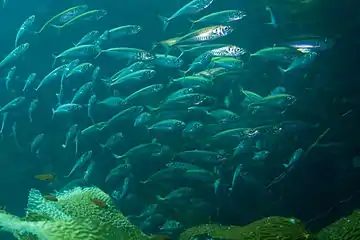

Mackerel species typically have vertical stripes on their backs and deeply forked tails. Many are restricted in their distribution ranges and live in separate populations or fish stocks based on geography. Some stocks migrate in large schools along the coast to suitable spawning grounds, where they spawn in fairly shallow waters. After spawning they return the way they came in smaller schools to suitable feeding grounds, often near an area of upwelling. From there they may move offshore into deeper waters and spend the winter in relative inactivity. Other stocks migrate across oceans.

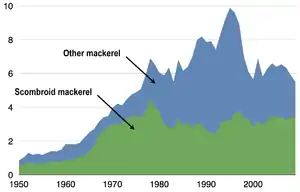

Smaller mackerel are forage fish for larger predators, including larger mackerel and Atlantic cod.[2] Flocks of seabirds, whales, dolphins, sharks, and schools of larger fish such as tuna and marlin follow mackerel schools and attack them in sophisticated and cooperative ways. Mackerel flesh is high in omega-3 oils and is intensively harvested by humans. In 2009, over 5 million tons were landed by commercial fishermen.[1] Sport fishermen value the fighting abilities of the king mackerel.[3]

Species

Over 30 different species, principally belonging to the family Scombridae, are commonly referred to as mackerel. The term "mackerel" is derived from Old French and may have originally meant either "marked, spotted" or "pimp, procurer". The latter connection is not altogether clear, but mackerel spawn enthusiastically in shoals near the coast, and medieval ideas on animal procreation were creative.[4]

Scombroid mackerels

About 21 species in the family Scombridae are commonly called mackerel. The type species for the scombroid mackerel is the Atlantic mackerel, Scomber scombrus. Until recently, Atlantic chub mackerel and Indo-Pacific chub mackerel were thought to be subspecies of the same species. In 1999, Collette established, on molecular and morphological considerations, that these are separate species.[5] Mackerel are smaller with shorter lifecycles than their close relatives, the tuna, which are also members of the same family.[6][7]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

Scombrini, the true mackerels

The true mackerels belong to the tribe Scombrini.[8] The tribe consists of seven species, each belonging to one of two genera: Scomber or Rastrelliger.[9][10]

| True Mackerels (tribe Scombrini) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

| Short mackerel | Rastrelliger brachysoma (Bleeker, 1851) |

34.5 cm (13.6 in) | 20 cm (7.9 in) | 2.72 | [11] | [12] | |||

| Island mackerel | R. faughni (Matsui, 1967) |

20 cm (7.9 in) | 0.75 kg (1.7 lb) | 3.4 | [14] | ||||

| Indian mackerel | R. kanagurta (Cuvier, 1816) |

35 cm (14 in) | 25 cm (9.8 in) | 4 years | 3.19 | [16] | [17] | ||

| Blue mackerel | Scomber australasicus (Cuvier, 1832) |

44 cm (17 in) | 30 cm (12 in) | 1.36 kg (3.0 lb) | 4.2 | [19] | |||

| Atlantic chub mackerel | S. colias (Gmelin, 1789) |

3.91 | [21] | ||||||

| Chub mackerel | S. japonicus (Houttuyn, 1782) |

64 cm (25 in) | 30 cm (12 in) | 2.9 kg (6.4 lb) | 18 years | 3.09 | [23] | [24] | |

| Atlantic mackerel | S. scombrus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

66 cm (26 in) | 30 cm (12 in) | 3.4 kg (7.5 lb) | 12 years west 18 years east |

3.65 | [26] | [27] | |

Scomberomorini, the Spanish mackerels

The Spanish mackerels belong to the tribe Scomberomorini, which is the "sister tribe" of the true mackerels.[28] This tribe consists of 21 species in all—18 of those are classified into the genus Scomberomorus,[29] two into Grammatorcynus,[30] and a single species into the monotypic genus Acanthocybium.[31]

| Spanish Mackerels (tribe Scomberomorini) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

| Wahoo | Acanthocybium solandri (Cuvier in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1832) |

250 cm | 170 cm | 83 kg | years | 4.4 | [32] | ||

| Shark mackerel | Grammatorcynus bicarinatus (Quoy & Gaimard, 1825) |

112 cm | cm | 13.5 kg | years | 4.5 | [34] | ||

| Double-lined mackerel | G. bilineatus (Rüppell, 1836) |

100 cm | 50 cm | 3.5 kg | years | 4.18 | [36] | ||

| Serra Spanish mackerel | Scomberomorus brasiliensis (Collette, Russo & Zavala-Camin, 1978) |

cm | cm | kg | years | 3.31 | [38] | ||

| King mackerel | S. cavalla (Cuvier, 1829) |

184 cm | 70 cm | 45 kg | 14 years | 4.5 | [40] | [41] | |

| Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel | S. commerson (Lacepède, 1800) |

240 cm | 120 cm | kg | years | 4.5 | [43] | [44] | |

| Monterey Spanish mackerel | S. concolor (Lockington, 1879) |

cm | cm | kg | years | 4.24 | [46] | ||

| Indo-Pacific king mackerel | S. guttatus (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) |

76 cm | 55 cm | kg | years | 4.28 | [48] | [49] | |

| Korean mackerel | S. koreanus (Kishinouye, 1915) |

150 cm | 60 cm | 15 kg | years | 4.2 | [51] | ||

| Streaked Spanish mackerel | S. lineolatus (Cuvier, 1829) |

80 cm | 70 cm | kg | years | 4.5 | [53] | ||

| Atlantic Spanish mackerel | S. maculatus (Mitchill, 1815) |

91 cm | cm | 5.89 kg | 5 years | 4.5 | [55] | [56] | |

| Papuan Spanish mackerel | S. multiradiatus Munro, 1964 |

35 cm | cm | 0.5 kg | years | 4.0 | [58] | ||

| Australian spotted mackerel | S. munroi (Collette & Russo, 1980) |

104 cm | cm | 10.2 kg | years | 4.3 | [60] | ||

| Japanese Spanish mackerel | S. niphonius (Cuvier, 1832) |

100 cm | cm | 7.1 kg | years | 4.5 | [62] | [63] | |

| Queen mackerel | S. plurilineatus Fourmanoir, 1966 |

120 cm | cm | 12.5 kg | years | 4.2 | [65] | ||

| Queensland school mackerel | S. queenslandicus (Munro, 1943) |

100 cm | 80 cm | 12.2 kg | years | 4.5 | [67] | ||

| Cero mackerel | S. regalis (Bloch, 1793) |

183 cm | cm | 7.8 kg | years | 4.5 | [69] | ||

| Broadbarred king mackerel | S. semifasciatus (Macleay, 1883) |

120 cm | cm | kg | 10 years | 4.5 | [71] | ||

| Pacific sierra | S. sierra (Cuvier, 1832) |

99 cm | 60 cm | 8.2 kg | years | 4.5 | [73] | ||

| Chinese mackerel | S. sinensis (Cuvier, 1832) |

247 cm | 100 cm | kg | years | 4.5 | [75] | ||

| West African Spanish mackerel | S. tritor (Cuvier, 1832) |

cm | cm | kg | years | 4.26 | [77] | ||

Other mackerel

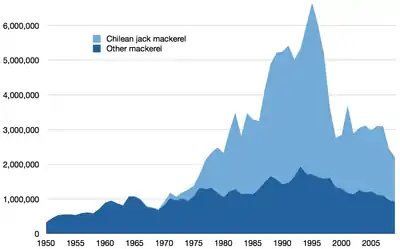

In addition, a number of species with mackerel-like characteristics in the families Carangidae, Hexagrammidae and Gempylidae are commonly referred to as mackerel. Some confusion had occurred between the Pacific jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus) and the heavily harvested Chilean jack mackerel (T. murphyi). These have been thought at times to be the same species, but are now recognised as separate species.[79]

| Other mackerel species | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

| Scombridae Gasterochisma |

Butterfly mackerel | Gasterochisma melampus Richardson, 1845 | 175 cm | 153 cm | kg | years | 4.4 | [80] | ||

| Carangidae Jack mackerel |

Atlantic horse mackerel | Trachurus trachurus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 70 cm | 22 cm | 2.0 kg | years | 3.64 | [82] | [83] | Not assessed |

| Blue jack mackerel | T. picturatus (Bowdich, 1825) | 60 cm | 25 cm | kg | years | 3.32 | [84] | |||

| Cape horse mackerel | T. capensis (Castelnau, 1861) | 60 cm | 30 cm | kg | years | 3.47 | [86] | [87] | Not assessed[88] | |

| Chilean jack mackerel | T. murphyi (Nichols, 1920) | 70 cm | 45 cm | kg | 16 years | 3.49 | [89] | [90] | ||

| Cunene horse mackerel | T. trecae (Cadenat, 1950) | 35 cm | cm | 2.0 kg | years | 3.49 | [92] | [93] | Not assessed | |

| Greenback horse mackerel | T. declivis (Jenyns, 1841) | 64 cm | 42 cm | kg | 25 years | 3.93 | [94] | [95] | Not assessed[96] | |

| Japanese horse mackerel | T. japonicus (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844) | 50 cm | 35 cm | 0.66 kg | 12 years | 3.4 | [97] | [98] | Not assessed | |

| Mediterranean horse mackerel | T. mediterraneus (Steindachner, 1868) | 60 cm | 30 cm | kg | years | 3.59 | [99] | [100] | Not assessed | |

| Pacific jack mackerel | T. symmetricus (Ayres, 1855) | 81 cm | 55 cm | kg | 30 years | 3.56 | [101] | |||

| Yellowtail horse mackerel | T. novaezelandiae (Richardson, 1843) | 50 cm | 35 cm | kg | 25 years | 4.5 | [103] | Not assessed | ||

| Gempylidae Snake mackerel |

Black snake mackerel | Nealotus tripes (Johnson, 1865) | 25 cm | 15 cm | kg | years | 4.2 | [104] | Not assessed | |

| Blacksail snake mackerel | Thyrsitoides marleyi (Fowler, 1929) | 200 cm | 100 cm | kg | years | 4.19 | [105] | Not assessed | ||

| Snake mackerel | Gempylus serpens (Cuvier, 1829) | 100 cm | 60 cm | kg | years | 4.35 | [106] | Not assessed | ||

| Violet snake mackerel | Nesiarchus nasutus (Johnson, 1862) | 130 cm | 80 cm | kg | years | 4.33 | [107] | Not assessed | ||

| * White snake mackerel | Thyrsitops lepidopoides (Cuvier, 1832) | 40 cm | 25 cm | kg | years | 3.86 | [108] | Not assessed | ||

| Hexagrammidae | Okhotsk atka mackerel | Pleurogrammus azonus (Jordan & Metz, 1913) | 62 cm | cm | 1.6 kg | 12 years | 3.58 | [109] | [110] | Not assessed |

| Atka mackerel | P. monopterygius (Pallas, 1810) | 56.5 cm | cm | 2.0 kg | 14 years | 3.33 | [111] | Not assessed | ||

The term "mackerel" is also used as a modifier in the common names of other fish, sometimes indicating the fish has vertical stripes similar to a scombroid mackerel:

- Mackerel icefish—Champsocephalus gunnari

- Mackerel pike—Cololabis saira

- Mackerel scad—Decapterus macarellus

- Mackerel shark—several species

- Shortfin mako shark—Isurus oxyrinchus

- Mackerel tuna—Euthynnus affinis

- Mackerel tail goldfish—Carassius auratus

By extension, the term is applied also to other species such as the mackerel tabby cat,[112] and to inanimate objects such as the altocumulus mackerel sky cloud formation.[113][114]

Characteristics

Most mackerel belong to the family Scombridae, which also includes tuna and bonito. Generally, mackerel are much smaller and slimmer than tuna, though in other respects, they share many common characteristics. Their scales, if present at all, are extremely small. Like tuna and bonito, mackerel are voracious feeders, and are swift and manoeuvrable swimmers, able to streamline themselves by retracting their fins into grooves on their bodies. Like other scombroids, their bodies are cylindrical with numerous finlets on the dorsal and ventral sides behind the dorsal and anal fins, but unlike the deep-bodied tuna, they are slim.[115]

The type species for scombroid mackerels is the Atlantic mackerel, Scomber scombrus. These fish are iridescent blue-green above with a silvery underbelly and 200-30 near-vertical wavy black stripes running across their upper bodies.[26][117]

The prominent stripes on the back of mackerels seemingly are there to provide camouflage against broken backgrounds. That is not the case, though, because mackerel live in midwater pelagic environments which have no background.[118] However, fish have an optokinetic reflex in their visual systems that can be sensitive to moving stripes.[119] For fish to school efficiently, they need feedback mechanisms that help them align themselves with adjacent fish, and match their speed. The stripes on neighbouring fish provide "schooling marks", which signal changes in relative position.[118][120]

A layer of thin, reflecting platelets is seen on some of the mackerel stripes. In 1998, E J Denton and D M Rowe argued that these platelets transmit additional information to other fish about how a given fish moves. As the orientation of the fish changes relative to another fish, the amount of light reflected to the second fish by this layer also changes. This sensitivity to orientation gives the mackerel "considerable advantages in being able to react quickly while schooling and feeding."[121]

Mackerel range in size from small forage fish to larger game fish. Coastal mackerel tend to be small.[122] The king mackerel is an example of a larger mackerel. Most fish are cold-blooded, but exceptions exist. Certain species of fish maintain elevated body temperatures. Endothermic bony fishes are all in the suborder Scombroidei and include the butterfly mackerel, a species of primitive mackerel.[123]

Mackerel are strong swimmers. Atlantic mackerel can swim at a sustained speed of 0.98 m/sec with a burst speed of 5.5 m/sec,[124][125] while chub mackerel can swim at a sustained speed of 0.92 m/sec with a burst speed of 2.25 m/sec.[115]

Distribution

Most mackerel species have restricted distribution ranges.[115]

- Atlantic Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus) occupy the waters off the east coast of North America from the Cape Cod area south to the Yucatan Peninsula. Its population is considered to include two fish stocks, defined by geography. As summer approaches, one stock moves in large schools north from Florida up the coast to spawn in shallow waters off the New England coast. It then returns to winter in deeper waters off Florida. The other stock migrates in large schools along the coast from Mexico to spawn in shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico off Texas. It then returns to winter in deeper waters off the Mexican coast.[56] These stocks are managed separately, even though genetically they are identical.[57]

- The Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) is a coastal species found only in the north Atlantic. The stock on the west side of the Atlantic is largely independent of the stock on the east side. The stock on the east Atlantic currently operates as three separate stocks, the southern, western and North Sea stocks, each with their own migration patterns. Some mixing of the east Atlantic stocks takes place in feeding grounds towards the north, but there is almost no mixing between the east and west Atlantic stocks.[5][128][129][130][131]

- Another common coastal species, the chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus), is absent from the Atlantic Ocean but is widespread across both hemispheres in the Pacific, where its migration patterns are somewhat similar to those of Atlantic mackerel. In the northern hemisphere, chub mackerel migrate northwards in the summer to feeding grounds, and southwards in the winter when they spawn in relatively shallow waters. In the southern hemisphere the migrations are reversed. After spawning, some stocks migrate down the continental slope to deeper water and spend the rest of the winter in relative inactivity.[23]

- The Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi), the most intensively harvested mackerel-like species, is found in the south Pacific from West Australia to the coasts of Chile and Peru.[89] A sister species, the Pacific jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus), is found in the north Pacific. The Chilean jack mackerel occurs along the coasts in upwelling areas, but also migrates across the open ocean. Its abundance can fluctuate markedly as ocean conditions change,[91] and is particularly affected by the El Niño.

Three species of jack mackerels are found in coastal waters around New Zealand: the Australasian, Chilean, and Pacific jack mackerels. They are mainly captured using purse seine nets, and are managed as a single stock that includes multiple species.[132]

Some mackerel species migrate vertically. Adult snake mackerel conduct a diel vertical migration, staying in deeper water during the day and rising to the surface at night to feed. The young and juveniles also migrate vertically, but in the opposite direction, staying near the surface during the day and moving deeper at night.[133] This species feeds on squid, pelagic crustaceans, lanternfishes, flying fishes, sauries, and other mackerel.[134] It is, in turn, preyed upon by tuna and marlin.[135]

Lifecycle

Mackerel are prolific broadcast spawners, and must breed near the surface of the water because the eggs of the females float. Individual females lay between 300,000 and 1,500,000 eggs.[115] Their eggs and larvae are pelagic, that is, they float free in the open sea. The larvae and juvenile mackerel feed on zooplankton. As adults, they have sharp teeth, and hunt small crustaceans such as copepods, forage fish, shrimp, and squid. In turn, they are hunted by larger pelagic animals such as tuna, billfish, sea lions, sharks, and pelicans.[24][41][136]

Off Madagascar, spinner sharks follow migrating schools of mackerel.[137] Bryde's whales feed on mackerel when they can find them. They use several feeding methods, including skimming the surface, lunging, and bubble nets.[138]

Fisheries

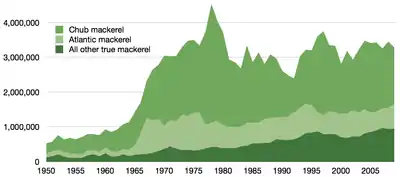

Chub mackerel, Scomber japonicus, are the most intensively fished scombroid mackerel. They account for about half the total capture production of scombroid mackerels.[1] As a species, they are easily confused with Atlantic mackerel. Chub mackerel migrate long distances in oceans and across the Mediterranean. They can be caught with drift nets and suitable trawls, but are most usually caught with surround nets at night by attracting them with lampara lamps.[139]

The remaining catch of scombroid mackerels is divided equally between the Atlantic mackerel and all other scombroid mackerels. Just two species account for about 75% of the total catch of scombroid mackerels.[1]

Chilean jack mackerel are the most commonly fished nonscombroid mackerel, fished as heavily as chub mackerel.[1][90] The species has been overfished, and its fishery may now be in danger of collapsing.[140][141]

Smaller mackerel behave like herrings, and are captured in similar ways.[142] Fish species like these, which school near the surface, can be caught efficiently by purse seining. Huge purse-seine vessels use spotter planes to locate the schooling fish. Then they close in using sophisticated sonar to track the shape of the school, which is then encircled with fast auxiliary boats that deploy purse seines as they speed around the school.[143][144]

Suitably designed trollers can also catch mackerels effectively when they swim near the surface. Trollers typically have several long booms which they lift and drop with "topping lifts". They haul their lines with electric or hydraulic reels.[145] Fish aggregating devices are also used to target mackerel.[146]

| Images and videos | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

Management

The North Sea has been overfished to the point where the ecological balance has become disrupted and many jobs in the fishing industry have been lost.[147]

The Southeast US region spans the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, and the US Southeast Atlantic. Overfishing of king and Spanish mackerel occurred in the 1980s. Regulations were introduced to restrict the size, fishing locations, and bag limits for recreational fishers and commercial fishers. Gillnets were banned in waters off Florida. By 2001, the mackerel stocks had bounced back.[148]

As food

Mackerel is an important food fish that is consumed worldwide.[149] As an oily fish, it is a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids.[150] The flesh of mackerel spoils quickly, especially in the tropics, and can cause scombroid food poisoning. Accordingly, it should be eaten on the day of capture, unless properly refrigerated or cured.[151]

Mackerel preservation is not simple. Before the 19th-century development of canning and the widespread availability of refrigeration, salting and smoking were the principal preservation methods available.[152] Historically in England, this fish was not preserved, but was consumed only in its fresh form. However, spoilage was common, leading the authors of The Cambridge Economic History of Europe to remark: "There are more references to stinking mackerel in English literature than to any other fish!"[142] In France, mackerel was traditionally pickled with large amounts of salt, which allowed it to be sold widely across the country.[142]

References

- Based on data sourced from the relevant FAO Species Fact Sheets

- Daan, N. (December 1973). "A quantitative analysis of the food intake of North Sea cod, Gadus Morhua". Netherlands Journal of Sea Research. 6 (4): 479–517. Bibcode:1973NJSR....6..479D. doi:10.1016/0077-7579(73)90002-1.

- King mackerel. Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (11th ed.). Merriam Webster. 2008. p. 688. ISBN 9780877798095.

- "Mackerel". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomber scombrus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Juan-Jorda, MJ; Mosqueira, I; Cooper, AB; Freire, J; Dulvy, NK (2011). "Global population trajectories of tunas and their relatives". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (51): 20650–20655. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820650J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107743108. PMC 3251139. PMID 22143785.

- "Tuna and mackerel populations have reduced by 60% in the last century". ScienceDaily. 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.

- "Scombrini". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Scomber". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Rastrelliger". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Rastrelliger brachysoma" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Rastrelliger brachysoma (Bleeker, 1851)". FAO. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Rastrelliger brachysoma". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Rastrelliger faughni" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Rastrelliger faughni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Rastrelliger kanagurta" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Rastrelliger kanagurta (Cuvier, 1817)". FAO. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Rastrelliger kanagurta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomber australasicus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomber australasicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomber colias" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomber colias". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomber japonicus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomber japonicus (Houttuyn, 1782)". FAO. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomber japonicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomber scombrus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomber scombrus (Linnaeus, 1758)". FAO. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Scomberomorini". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Scomberomorus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Grammatorcynus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Acanthocybium". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Acanthocybium solandri" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Acanthocybium solandri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Grammatorcynus bicarinatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B, Fox W, Nelson R (2011). "Grammatorcynus bicarinatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Grammatorcynus bilineatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Grammatorcynus bilineatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus brasiliensis" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus brasiliensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus cavalla" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomberomorus cavalla (Cuvier, 1829)". FAO. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus cavalla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus commerson" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomberomorus commerson (Lacepède, 1800)". FAO. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus commerson". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus concolor" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus concolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus guttatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomberomorus guttatus (Bloch & Schneider, 1801)". FAO. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus guttatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus koreanus" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus koreanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus lineolatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus lineolatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus maculatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomberomorus maculatus (Mitchill, 1815)". FAO. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomber maculatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus multiradiatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus multiradiatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus munroi" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomber munroi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus niphonius" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Scomberomorus niphonius (Cuvier, 1831)". FAO. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus niphonius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus plurilineatus" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Rastrelliger plurilineatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus queenslandicus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus queenslandicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus regalis" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus regalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus semifasciatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus semifasciatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus sierra" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus sierra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus sinensis" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus sinensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Scomberomorus tritor" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Collette B; et al. (2011). "Scomberomorus tritor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Poulin, E; Cárdenas, L; Hernández, CE; Kornfield, I; Ojeda, FP (2004). "Resolution of the taxonomic status of Chilean and Californian jack mackerels using mitochondrial DNA sequence". Journal of Fish Biology. 65 (4): 1160–1164. doi:10.1111/j.0022-1112.2004.00514.x.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Gasterochisma melampus" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Collette, B.; Boustany, A.; Carpenter, K.E.; Di Natale, A.; Fox, W.; Graves, J.; Juan Jorda, M.; Miyabe, N.; Nelson, R.; Oxenford, H.; et al. (2011). "Gasterochisma melampus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus trachurus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus trachurus (Linnaeus, 1758)". FAO. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus picturatus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Smith-Vaniz B, Robertson R, Dominici-Arosemena A (2011). "Trachurus picturatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus capensis" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus capensis (Castelnau, 1861)". FAO. Archived from the original on 26 November 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Species Phallomedusa solida (Martens, 1878)". Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Biological Resources Study. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus murphyi" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus murphyi (Nichols, 1920)". FAO. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Smith-Vaniz B, Robertson R, Dominici-Arosemena A (2010). "Trachurus murphyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus trecae" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus trecae (Cadenat, 1949)". FAO. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus declivis" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus declivis (Jenyns, 1841)". FAO. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Phallomedusa solida (Martens, 1878)". Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Biological Resources Study. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus japonicus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus japonicus (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844)". FAO. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus mediterraneus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Trachurus mediterraneus (Steindachner, 1868)". FAO. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus symmetricus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Smith-Vaniz B, Robertson R, Dominici-Arosemena A (2011). "Trachurus symmetricus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Trachurus novaezelandiae" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Nealotus tripes" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Thyrsitoides marleyi" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Gempylus serpens" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Nesiarchus nasutus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Thyrsitops lepidopoides" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Pleurogrammus azonus" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Pleurogrammus azonus (Jordan & Metz, 1913)". FAO. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Pleurogrammus monopterygius" in FishBase. March 2012 version.

- "Glossary of definitions of cat terms for the breeder". Cats online. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Downing, L. L. (2013). Metereology of Clouds. p. 154. ISBN 9781491804339.

- Ahrens, C. Donald; Henson, Robert (2015). Metereology Today. Cengage Learning. p. 153. ISBN 9781305480629.

- "FAO Fact Sheet: Biological characteristics of tuna". Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- "Species Fact Sheet: Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus)". Nova Scotia Fisheries and Aquaculture. 1 May 2007. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- "Atlantic mackerel". FishWatch. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- Denton, EJ; Rowe, DM (1998). "Bands against stripes on the backs of mackerel, Scomber scombrus L." Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 265 (1401): 1051–1058. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0398. PMC 1689176.

- Shaw, E; Tucker, A (1965). "The optomotor reaction of schooling carangid fishes". Animal Behaviour. 13 (2–3): 330–336. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(65)90052-7. PMID 5835850.

- Bone, Q; Moore, RH (2008). Biology of Fishes. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 418–422. ISBN 978-0-415-37562-7.

- Rowe, DM; Denton, EJ (1997). "The physical basis of reflective communication between fish, with special reference to the horse mackerel, Trachurus trachurus". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 352 (1353): 531–549. Bibcode:1997RSPTB.352..531R. doi:10.1098/rstb.1997.0037. PMC 1691948.

- Lal, BV; Fortune, K (2000). The Pacific Islands: An encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780824822651.

- Block, BA; Finnerty, JR (1993). "Endothermy in fishes: a phylogenetic analysis of constraints, predispositions, and selection pressures". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 40 (3): 283–302. doi:10.1007/BF00002518. S2CID 28644501.

- Wardle, CS; He, P (1988). "Burst swimming speeds of mackerel, Scomber scombrus". Journal of Fish Biology. 32 (3): 471–478. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1988.tb05382.x.

- Wardle, CS; He, P (1988). "Endurance at intermediate swimming speeds of Atlantic mackerel, Scomber scombrus L., herring, Clupea harengus L., and saithe, Pollachius virens L". Journal of Fish Biology. 33 (2): 255–266. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1988.tb05468.x.

- "Pelagic species". Pelagic Freezer-trawler Association. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- "Mackerel". Institute of Marine Research. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- Uriarte, A; Alvarez, P; Iversen, S; Molloy, J; Villamor, B; Martíns, MM; Myklevoll, S (September 2001). Spatial pattern of migration and recruitment of North East Atlantic mackerel (PDF). ICES Annual Science Conference. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2018.

- "Northeast Atlantic mackerel stocks". The FishSite. 25 April 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus)". The Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012.

- Walsh, M; Reid, DG; Turrell, WR (1995). "Understanding mackerel migration off Scotland: Tracking with echosounders and commercial data, and including environmental correlates and behaviour". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 52 (6): 925–939. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1995.0089.

- "Jack Mackerel". NZ Forest and Bird. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- Burton, R. (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7266-7.

- McEachran, J.D. & Fechhelm, J.D. (2005). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Scorpaeniformes to Tetraodontiformes. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70634-7.

- Peterson, R.T.; Eschmeyer, W.N. & Herald, E.S. (1999). A Field Guide to Pacific Coast Fishes: North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-00212-2.

- "Forage species". FAO. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 466–468. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- "Bryde's Whale (Balaenoptera edeni)". Noaa Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "Chub mackerel". Sicilian Fish on the Road. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "In mackerel's plunder, hints of epic fish collapse". The New York Times. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018.

- "Lords of the fish". iWatch News. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012.

- Clapham, JH; Postan, MM; Rich, EE (1941). The Cambridge economic history of Europe. CUP Archive. pp. 166–168. ISBN 978-0-521-08710-0.

- "Fishing vessel types: Purse seiners". FAO. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Gabriel, O; von Brandt, A; Lange, K; Dahm, E; Wendt, T (2005). Seining in fresh and sea water. Fish catching methods of the world. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 431–448. ISBN 9780852382806.

- "Fishing Vessel type: Trollers". FAO. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019.

- "The FAD FAQ". Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 0-09-189780-7.

- "FISHERY COUNTRY PROFILE: THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA" (PDF). FAO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2017.

- Croker, Richard Symonds (1933). The California mackerel fishery. Division of Fish and Game of California. pp. 9–10.

- Jersey Seafood Nutrition and Health, State of New Jersey Department of Agriculture, archived from the original on 1 July 2017, retrieved 6 April 2012

- "Scombrotoxin (Histamine)". Food Safety Watch. November 2007. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012.

- Croker (1933), pp. 104-105

Further reading

- Ahlstrom, EH (1956). "Eggs and larvae of anchovy, jack mackerel, and Pacific mackerel" (PDF). CalCOFI Reports. 5: 33–42.

- Bertrand, A; Barbieri, MA; Gerlotto, F; Leiva, F; Cordova, J (2006). "Determinism and plasticity of fish schooling behaviour as exemplified by the South Pacific jack mackerel Trachurus murphyi" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 311: 145–156. Bibcode:2006MEPS..311..145B. doi:10.3354/meps311145. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2019.

- Bigelow HB and Schroeder WC (1953) Fishes of the Gulf of Maine: Mackerel Fisheries Bulletin, Volume 53, Number 74, United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Burton M and Burton R (2002) International Wildlife Encyclopedia Marshall Cavendish, pp. 1517–1518. ISBN 978-0-7614-7266-7.

- Hays, GC (1996). "Large-scale patterns of diel vertical migration in the North Atlantic" (PDF). Deep-Sea Research Part I. 43 (10): 1601–1615. Bibcode:1996DSRI...43.1601H. doi:10.1016/s0967-0637(96)00078-7.

- Keay JN (2001) Handling and processing mackerel Torry advisory note 66.

- Masuda, R; Shoji, J; Nakatama Sand, Tanaka T (2003). "Development of schooling behavior in Spanish mackerel Scomberomorus niphonius during early ontogeny" (PDF). Fisheries Science. 69 (4): 772–776. doi:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2003.00685.x.

- Nakayama, S; Masuda, R; Tanaka, M (2007). "Onsets of schooling behavior and social transmission in chub mackerel Scomber japonicus" (PDF). Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 61 (9): 1383–1390. doi:10.1007/s00265-007-0368-4. S2CID 56667.

- Nakayama, A; Masuda, R; Shoji, J; Takeuchi, T; Tanaka, M (2003). "Effect of prey items on the development of schooling behavior in chub mackerel Scomber japonicus in the laboratory" (PDF). Fisheries Science. 69 (4): 670–676. doi:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2003.00673.x.

- Nakayama, S; Masuda, R; Tanaka, M (2007). "Onsets of schooling behavior and social transmission in chub mackerel Scomber japonicus". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 61 (9): 1383–1390. doi:10.1007/s00265-007-0368-4. JSTOR 27823518. S2CID 56667.

- SPRFMO(2009) Information describing Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi) fisheries relating to the South Pacific Regional Fishery Management Organisation Working draft.

External links

| Look up mackerel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Atlantic Mackerel British Marine Life Study Society. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Mackerel nutrition facts

- Fishing for mackerel

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

.png.webp)