Matrix multiplication

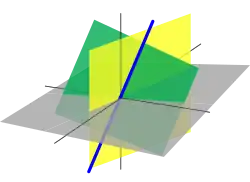

In mathematics, particularly in linear algebra, matrix multiplication is a binary operation that produces a matrix from two matrices. For matrix multiplication, the number of columns in the first matrix must be equal to the number of rows in the second matrix. The resulting matrix, known as the matrix product, has the number of rows of the first and the number of columns of the second matrix. The product of matrices A and B is denoted as AB.[1][2]

Matrix multiplication was first described by the French mathematician Jacques Philippe Marie Binet in 1812,[3] to represent the composition of linear maps that are represented by matrices. Matrix multiplication is thus a basic tool of linear algebra, and as such has numerous applications in many areas of mathematics, as well as in applied mathematics, statistics, physics, economics, and engineering.[4][5] Computing matrix products is a central operation in all computational applications of linear algebra.

Notation

This article will use the following notational conventions: matrices are represented by capital letters in bold, e.g. A; vectors in lowercase bold, e.g. a; and entries of vectors and matrices are italic (since they are numbers from a field), e.g. A and a. Index notation is often the clearest way to express definitions, and is used as standard in the literature. The i, j entry of matrix A is indicated by (A)ij, Aij or aij, whereas a numerical label (not matrix entries) on a collection of matrices is subscripted only, e.g. A1, A2, etc.

Definition

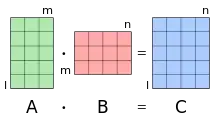

If A is an m × n matrix and B is an n × p matrix,

the matrix product C = AB (denoted without multiplication signs or dots) is defined to be the m × p matrix[6][7][8][9]

such that

for i = 1, ..., m and j = 1, ..., p.

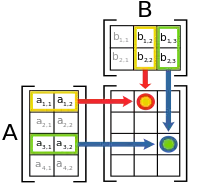

That is, the entry of the product is obtained by multiplying term-by-term the entries of the ith row of A and the jth column of B, and summing these n products. In other words, is the dot product of the ith row of A and the jth column of B.[1]

Therefore, AB can also be written as

Thus the product AB is defined if and only if the number of columns in A equals the number of rows in B,[2] in this case n.

In most scenarios, the entries are numbers, but they may be any kind of mathematical objects for which an addition and a multiplication are defined, that are associative, and such that the addition is commutative, and the multiplication is distributive with respect to the addition. In particular, the entries may be matrices themselves (see block matrix).

Illustration

The figure to the right illustrates diagrammatically the product of two matrices A and B, showing how each intersection in the product matrix corresponds to a row of A and a column of B.

The values at the intersections marked with circles are:

Fundamental applications

Historically, matrix multiplication has been introduced for facilitating and clarifying computations in linear algebra. This strong relationship between matrix multiplication and linear algebra remains fundamental in all mathematics, as well as in physics, engineering and computer science.

Linear maps

If a vector space has a finite basis, its vectors are each uniquely represented by a finite sequence of scalars, called a coordinate vector, whose elements are the coordinates of the vector on the basis. These coordinate vectors form another vector space, which is isomorphic to the original vector space. A coordinate vector is commonly organized as a column matrix (also called column vector), which is a matrix with only one column. So, a column vector represents both a coordinate vector, and a vector of the original vector space.

A linear map A from a vector space of dimension n into a vector space of dimension m maps a column vector

onto the column vector

The linear map A is thus defined by the matrix

and maps the column vector to the matrix product

If B is another linear map from the preceding vector space of dimension m, into a vector space of dimension p, it is represented by a matrix A straightforward computation shows that the matrix of the composite map is the matrix product The general formula ) that defines the function composition is instanced here as a specific case of associativity of matrix product (see § Associativity below):

System of linear equations

The general form of a system of linear equations is

Using same notation as above, such a system is equivalent with the single matrix equation

Dot product, bilinear form and inner product

The dot product of two column vectors is the matrix product

where is the row vector obtained by transposing and the resulting 1×1 matrix is identified with its unique entry.

More generally, any bilinear form over a vector space of finite dimension may be expressed as a matrix product

and any inner product may be expressed as

where denotes the conjugate transpose of (conjugate of the transpose, or equivalently transpose of the conjugate).

General properties

Matrix multiplication shares some properties with usual multiplication. However, matrix multiplication is not defined if the number of columns of the first factor differs from the number of rows of the second factor, and it is non-commutative,[10] even when the product remains definite after changing the order of the factors.[11][12]

Non-commutativity

An operation is commutative if, given two elements A and B such that the product is defined, then is also defined, and

If A and B are matrices of respective sizes and , then is defined if , and is defined if . Therefore, if one of the products is defined, the other is not defined in general. If , the two products are defined, but have different sizes; thus they cannot be equal. Only if , that is, if A and B are square matrices of the same size, are both products defined and of the same size. Even in this case, one has in general

For example

but

This example may be expanded for showing that, if A is a matrix with entries in a field F, then for every matrix B with entries in F, if and only if where , and I is the identity matrix. If, instead of a field, the entries are supposed to belong to a ring, then one must add the condition that c belongs to the center of the ring.

One special case where commutativity does occur is when D and E are two (square) diagonal matrices (of the same size); then DE = ED.[10] Again, if the matrices are over a general ring rather than a field, the corresponding entries in each must also commute with each other for this to hold.

Distributivity

The matrix product is distributive with respect to matrix addition. That is, if A, B, C, D are matrices of respective sizes m × n, n × p, n × p, and p × q, one has (left distributivity)

and (right distributivity)

This results from the distributivity for coefficients by

Product with a scalar

If A is a matrix and c a scalar, then the matrices and are obtained by left or right multiplying all entries of A by c. If the scalars have the commutative property, then

If the product is defined (that is, the number of columns of A equals the number of rows of B), then

- and

If the scalars have the commutative property, then all four matrices are equal. More generally, all four are equal if c belongs to the center of a ring containing the entries of the matrices, because in this case, cX = Xc for all matrices X.

These properties result from the bilinearity of the product of scalars:

Transpose

If the scalars have the commutative property, the transpose of a product of matrices is the product, in the reverse order, of the transposes of the factors. That is

where T denotes the transpose, that is the interchange of rows and columns.

This identity does not hold for noncommutative entries, since the order between the entries of A and B is reversed, when one expands the definition of the matrix product.

Complex conjugate

If A and B have complex entries, then

where * denotes the entry-wise complex conjugate of a matrix.

This results from applying to the definition of matrix product the fact that the conjugate of a sum is the sum of the conjugates of the summands and the conjugate of a product is the product of the conjugates of the factors.

Transposition acts on the indices of the entries, while conjugation acts independently on the entries themselves. It results that, if A and B have complex entries, one has

where † denotes the conjugate transpose (conjugate of the transpose, or equivalently transpose of the conjugate).

Associativity

Given three matrices A, B and C, the products (AB)C and A(BC) are defined if and only if the number of columns of A equals the number of rows of B, and the number of columns of B equals the number of rows of C (in particular, if one of the products is defined, then the other is also defined). In this case, one has the associative property

As for any associative operation, this allows omitting parentheses, and writing the above products as

This extends naturally to the product of any number of matrices provided that the dimensions match. That is, if A1, A2, ..., An are matrices such that the number of columns of Ai equals the number of rows of Ai + 1 for i = 1, ..., n – 1, then the product

is defined and does not depend on the order of the multiplications, if the order of the matrices is kept fixed.

These properties may be proved by straightforward but complicated summation manipulations. This result also follows from the fact that matrices represent linear maps. Therefore, the associative property of matrices is simply a specific case of the associative property of function composition.

Complexity is not associative

Although the result of a sequence of matrix products does not depend on the order of operation (provided that the order of the matrices is not changed), the computational complexity may depend dramatically on this order.

For example, if A, B and C are matrices of respective sizes 10×30, 30×5, 5×60, computing (AB)C needs 10×30×5 + 10×5×60 = 4,500 multiplications, while computing A(BC) needs 30×5×60 + 10×30×60 = 27,000 multiplications.

Algorithms have been designed for choosing the best order of products, see Matrix chain multiplication. When the number n of matrices increases, it has been shown that the choice of the best order has a complexity of

Application to similarity

Any invertible matrix defines a similarity transformation (on square matrices of the same size as )

Similarity transformations map product to products, that is

In fact, one has

Square matrices

Let us denote the set of n×n square matrices with entries in a ring R, which, in practice, is often a field.

In , the product is defined for every pair of matrices. This makes a ring, which has the identity matrix I as identity element (the matrix whose diagonal entries are equal to 1 and all other entries are 0). This ring is also an associative R-algebra.

If n > 1, many matrices do not have a multiplicative inverse. For example, a matrix such that all entries of a row (or a column) are 0 does not have an inverse. If it exists, the inverse of a matrix A is denoted A−1, and, thus verifies

A matrix that has an inverse is an invertible matrix. Otherwise, it is a singular matrix.

A product of matrices is invertible if and only if each factor is invertible. In this case, one has

When R is commutative, and, in particular, when it is a field, the determinant of a product is the product of the determinants. As determinants are scalars, and scalars commute, one has thus

The other matrix invariants do not behave as well with products. Nevertheless, if R is commutative, and have the same trace, the same characteristic polynomial, and the same eigenvalues with the same multiplicities. However, the eigenvectors are generally different if

Powers of a matrix

One may raise a square matrix to any nonnegative integer power multiplying it by itself repeatedly in the same way as for ordinary numbers. That is,

Computing the kth power of a matrix needs k – 1 times the time of a single matrix multiplication, if it is done with the trivial algorithm (repeated multiplication). As this may be very time consuming, one generally prefers using exponentiation by squaring, which requires less than 2 log2 k matrix multiplications, and is therefore much more efficient.

An easy case for exponentiation is that of a diagonal matrix. Since the product of diagonal matrices amounts to simply multiplying corresponding diagonal elements together, the kth power of a diagonal matrix is obtained by raising the entries to the power k:

Abstract algebra

The definition of matrix product requires that the entries belong to a semiring, and does not require multiplication of elements of the semiring to be commutative. In many applications, the matrix elements belong to a field, although the tropical semiring is also a common choice for graph shortest path problems.[13] Even in the case of matrices over fields, the product is not commutative in general, although it is associative and is distributive over matrix addition. The identity matrices (which are the square matrices whose entries are zero outside of the main diagonal and 1 on the main diagonal) are identity elements of the matrix product. It follows that the n × n matrices over a ring form a ring, which is noncommutative except if n = 1 and the ground ring is commutative.

A square matrix may have a multiplicative inverse, called an inverse matrix. In the common case where the entries belong to a commutative ring r, a matrix has an inverse if and only if its determinant has a multiplicative inverse in r. The determinant of a product of square matrices is the product of the determinants of the factors. The n × n matrices that have an inverse form a group under matrix multiplication, the subgroups of which are called matrix groups. Many classical groups (including all finite groups) are isomorphic to matrix groups; this is the starting point of the theory of group representations.

Computational complexity

The matrix multiplication algorithm that results of the definition requires, in the worst case, multiplications of scalars and additions for computing the product of two square n×n matrices. Its computational complexity is therefore , in a model of computation for which the scalar operations require a constant time (in practice, this is the case for floating point numbers, but not for integers).

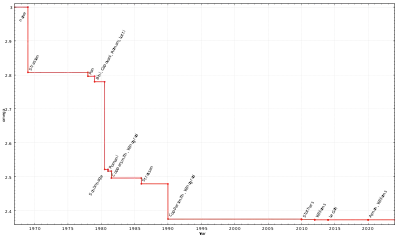

Rather surprisingly, this complexity is not optimal, as shown in 1969 by Volker Strassen, who provided an algorithm, now called Strassen's algorithm, with a complexity of [14] The exponent appearing in the complexity of matrix multiplication has been improved several times,[15][16][17][18][19][20] leading to the Coppersmith–Winograd algorithm with a complexity of O(n2.3755) (1990).[21][22] This algorithm has been slightly improved in 2010 by Stothers to a complexity of O(n2.3737),[23] in 2013 by Virginia Vassilevska Williams to O(n2.3729),[22][24] and in 2014 by François Le Gall to O(n2.3728639).[25] This was further refined in 2020 by Josh Alman and Virginia Vassilevska Williams to a final (up to date) complexity of O(n2.3728596).[26]

The greatest lower bound for the exponent of matrix multiplication algorithm is generally called . One has , because one has to read the elements of a matrix for multiplying it by another matrix. Thus . It is unknown whether . The largest known lower bound for matrix-multiplication complexity is Ω(n2 log(n)), for a restricted kind of arithmetic circuits, and is due to Ran Raz.[27]

Related complexities

The importance of the computational complexity of matrix multiplication relies on the facts that many algorithmic problems may be solved by means of matrix computation, and most problems on matrices have a complexity which is either the same as that of matrix multiplication (up to a multiplicative constant), or may be expressed in term of the complexity of matrix multiplication or its exponent

There are several advantages of expressing complexities in terms of the exponent of matrix multiplication. Firstly, if is improved, this will automatically improve the known upper bound of complexity of many algorithms. Secondly, in practical implementations, one never uses the matrix multiplication algorithm that has the best asymptotical complexity, because the constant hidden behind the big O notation is too large for making the algorithm competitive for sizes of matrices that can be manipulated in a computer. Thus expressing complexities in terms of provide a more realistic complexity, since it remains valid whichever algorithm is chosen for matrix computation.

Problems that have the same asymptotic complexity as matrix multiplication include determinant, matrix inversion, Gaussian elimination (see next section). Problems with complexity that is expressible in terms of include characteristic polynomial, eigenvalues (but not eigenvectors), Hermite normal form, and Smith normal form.

Matrix inversion, determinant and Gaussian elimination

In his 1969 paper, where he proved the complexity for matrix computation, Strassen proved also that matrix inversion, determinant and Gaussian elimination have, up to a multiplicative constant, the same computational complexity as matrix multiplication. The proof does not make any assumptions on matrix multiplication that is used, except that its complexity is for some

The starting point of Strassen's proof is using block matrix multiplication. Specifically, a matrix of even dimension 2n×2n may be partitioned in four n×n blocks

Under this form, its inverse is

provided that A and are invertible.

Thus, the inverse of a 2n×2n matrix may be computed with two inversions, six multiplications and four additions or additive inverses of n×n matrices. It follows that, denoting respectively by I(n), M(n) and A(n) = n2 the number of operations needed for inverting, multiplying and adding n×n matrices, one has

If one may apply this formula recursively:

If and one gets eventually

for some constant d.

For matrices whose dimension is not a power of two, the same complexity is reached by increasing the dimension of the matrix to a power of two, by padding the matrix with rows and columns whose entries are 1 on the diagonal and 0 elsewhere.

This proves the asserted complexity for matrices such that all submatrices that have to be inverted are indeed invertible. This complexity is thus proved for almost all matrices, as a matrix with randomly chosen entries is invertible with probability one.

The same argument applies to LU decomposition, as, if the matrix A is invertible, the equality

defines a block LU decomposition that may be applied recursively to and for getting eventually a true LU decomposition of the original matrix.

The argument applies also for the determinant, since it results from the block LU decomposition that

See also

- Matrix calculus, for the interaction of matrix multiplication with operations from calculus

- Other types of products of matrices:

- Block matrix multiplication

- Cracovian product, defined as A ∧ B = BTA

- Frobenius inner product, the dot product of matrices considered as vectors, or, equivalently the sum of the entries of the Hadamard product

- Hadamard product of two matrices of the same size, resulting in a matrix of the same size, which is the product entry-by-entry

- Kronecker product or tensor product, the generalization to any size of the preceding

- Khatri-Rao product and Face-splitting product

- Outer product, also called dyadic product or tensor product of two column matrices, which is

- Scalar multiplication

Notes

- "Comprehensive List of Algebra Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-03-25. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Nykamp, Duane. "Multiplying matrices and vectors". Math Insight. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Jacques Philippe Marie Binet", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Lerner, R. G.; Trigg, G. L. (1991). Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). VHC publishers. ISBN 978-3-527-26954-9.

- Parker, C. B. (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-07-051400-3.

- Lipschutz, S.; Lipson, M. (2009). Linear Algebra. Schaum's Outlines (4th ed.). McGraw Hill (USA). pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-07-154352-1.

- Riley, K. F.; Hobson, M. P.; Bence, S. J. (2010). Mathematical methods for physics and engineering. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86153-3.

- Adams, R. A. (1995). Calculus, A Complete Course (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 627. ISBN 0-201-82823-5.

- Horn, Johnson (2013). Matrix Analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-54823-6.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Matrix Multiplication". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Lipcshutz, S.; Lipson, M. (2009). "2". Linear Algebra. Schaum's Outlines (4th ed.). McGraw Hill (USA). ISBN 978-0-07-154352-1.

- Horn, Johnson (2013). "0". Matrix Analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54823-6.

- Motwani, Rajeev; Raghavan, Prabhakar (1995). Randomized Algorithms. Cambridge University Press. p. 280. ISBN 9780521474658.

- Volker Strassen (Aug 1969). "Gaussian elimination is not optimal". Numerische Mathematik. 13 (4): 354–356. doi:10.1007/BF02165411. S2CID 121656251.

- Victor Yakovlevich Pan (Oct 1978). "Strassen's Algorithm is not Optimal: Trilinear Technique of Aggregating, Uniting and Canceling for Constructing Fast Algorithms for Matrix Operations". Proc. 19th FOCS. pp. 166–176. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1978.34. S2CID 14348408.

- Dario Andrea Bini; Milvio Capovani; Francesco Romani; Grazia Lotti (Jun 1979). " complexity for approximate matrix multiplication". Information Processing Letters. 8 (5): 234–235. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(79)90113-3.

- A. Schönhage (1981). "Partial and total matrix multiplication". SIAM Journal on Computing. 10 (3): 434–455. doi:10.1137/0210032.

- Francesco Romani (1982). "Some properties of disjoint sums of tensors related to matrix multiplication". SIAM Journal on Computing. 11 (2): 263–267. doi:10.1137/0211020.

- D. Coppersmith; S. Winograd (1981). "On the asymptotic complexity of matrix multiplication". Proc. 22nd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS). pp. 82–90. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1981.27. S2CID 206558664.

- Volker Strassen (Oct 1986). "The asymptotic spectrum of tensors and the exponent of matrix multiplication". Proc. 27th Ann. Symp. on Foundation of Computer Science (FOCS). pp. 49–54. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1986.52. S2CID 15077423.

- D. Coppersmith; S. Winograd (Mar 1990). "Matrix multiplication via arithmetic progressions". Journal of Symbolic Computation. 9 (3): 251–280. doi:10.1016/S0747-7171(08)80013-2.

- Williams, Virginia Vassilevska. Multiplying matrices in time (PDF) (Technical Report). Stanford University.

- Stothers, Andrew James (2010). On the complexity of matrix multiplication (Ph.D. thesis). University of Edinburgh.

- Virginia Vassilevska Williams (2012). "Multiplying Matrices Faster than Coppersmith-Winograd". In Howard J. Karloff; Toniann Pitassi (eds.). Proc. 44th Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC). ACM. pp. 887–898. doi:10.1145/2213977.2214056.

- Le Gall, François (2014), "Powers of tensors and fast matrix multiplication", in Katsusuke Nabeshima (ed.), Proceedings of the 39th International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation (ISSAC), pp. 296–303, arXiv:1401.7714, Bibcode:2014arXiv1401.7714L, ISBN 978-1-4503-2501-1

- Alman, Josh; Williams, Virginia Vassilevska (2020), "A Refined Laser Method and Faster Matrix Multiplication", 32nd Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA 2021), arXiv:2010.05846

- Raz, Ran (January 2003). "On the Complexity of Matrix Product". SIAM Journal on Computing. 32 (5): 1356–1369. doi:10.1137/s0097539702402147. ISSN 0097-5397.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to matrix multiplication. |

| The Wikibook Linear Algebra has a page on the topic of: Matrix multiplication |

| The Wikibook Applicable Mathematics has a page on the topic of: Multiplying Matrices |

- Henry Cohn, Robert Kleinberg, Balázs Szegedy, and Chris Umans. Group-theoretic Algorithms for Matrix Multiplication. arXiv:math.GR/0511460. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 23–25 October 2005, Pittsburgh, PA, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 379–388.

- Henry Cohn, Chris Umans. A Group-theoretic Approach to Fast Matrix Multiplication. arXiv:math.GR/0307321. Proceedings of the 44th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 11–14 October 2003, Cambridge, MA, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 438–449.

- Coppersmith, D.; Winograd, S. (1990). "Matrix multiplication via arithmetic progressions". J. Symbolic Comput. 9 (3): 251–280. doi:10.1016/s0747-7171(08)80013-2.

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1991), Topics in Matrix Analysis, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-46713-1

- Knuth, D.E., The Art of Computer Programming Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. Addison-Wesley Professional; 3 edition (November 14, 1997). ISBN 978-0-201-89684-8. pp. 501.

- Press, William H.; Flannery, Brian P.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T. (2007), Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8.

- Ran Raz. On the complexity of matrix product. In Proceedings of the thirty-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. ACM Press, 2002. doi:10.1145/509907.509932.

- Robinson, Sara, Toward an Optimal Algorithm for Matrix Multiplication, SIAM News 38(9), November 2005. PDF

- Strassen, Volker, Gaussian Elimination is not Optimal, Numer. Math. 13, p. 354-356, 1969.

- Styan, George P. H. (1973), "Hadamard Products and Multivariate Statistical Analysis" (PDF), Linear Algebra and Its Applications, 6: 217–240, doi:10.1016/0024-3795(73)90023-2

- Williams, Virginia Vassilevska (2012-05-19). "Multiplying matrices faster than coppersmith-winograd". Proceedings of the 44th symposium on Theory of Computing - STOC '12. ACM. pp. 887–898. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.297.2680. doi:10.1145/2213977.2214056. ISBN 9781450312455. S2CID 14350287.