Group (mathematics)

In mathematics, a group is a set equipped with a binary operation that combines any two elements to form a third element in such a way that three conditions called group axioms are satisfied, namely associativity, identity and invertibility. One of the most familiar examples of a group is the set of integers together with the addition operation, but groups are encountered in numerous areas within and outside mathematics, and help focusing on essential structural aspects, by detaching them from the concrete nature of the subject of the study.[1][2]

Groups share a fundamental kinship with the notion of symmetry. For example, a symmetry group encodes symmetry features of a geometrical object: the group consists of the set of transformations that leave the object unchanged and the operation of combining two such transformations by performing one after the other. Lie groups arise as symmetry groups in geometry but appear also in the Standard Model of particle physics. The Poincaré group is a Lie group consisting of the symmetries of spacetime in special relativity. Point groups describe symmetry in molecular chemistry.

The concept of a group arose from the study of polynomial equations, starting with Évariste Galois in the 1830s, who introduced the term of group (groupe, in French) for the symmetry group of the roots of an equation, now called a Galois group. After contributions from other fields such as number theory and geometry, the group notion was generalized and firmly established around 1870. Modern group theory—an active mathematical discipline—studies groups in their own right.[a] To explore groups, mathematicians have devised various notions to break groups into smaller, better-understandable pieces, such as subgroups, quotient groups and simple groups. In addition to their abstract properties, group theorists also study the different ways in which a group can be expressed concretely, both from a point of view of representation theory (that is, through the representations of the group) and of computational group theory. A theory has been developed for finite groups, which culminated with the classification of finite simple groups, completed in 2004.[aa] Since the mid-1980s, geometric group theory, which studies finitely generated groups as geometric objects, has become an active area in group theory.

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

| Algebraic structures |

|---|

Definition and illustration

First example: the integers

One of the more familiar groups is the set of integers

together with addition.[3] For any two integers a and b, the sum a + b is also an integer; this closure property says that + is a binary operation on . The following properties of integer addition serve as a model for the group axioms in the definition below.

- For all integers a, b and c, one has (a + b) + c = a + (b + c). Expressed in words, adding a to b first, and then adding the result to c gives the same final result as adding a to the sum of b and c. This property is known as associativity.

- If a is any integer, then 0 + a = a and a + 0 = a. Zero is called the identity element of addition because adding it to any integer returns the same integer.

- For every integer a, there is an integer b such that a + b = 0 and b + a = 0. The integer b is called the inverse element of the integer a and is denoted −a.

The integers, together with the operation +, form a mathematical object belonging to a broad class sharing similar structural aspects. To appropriately understand these structures as a collective, the following definition is developed.

Definition

Richard Borcherds in Mathematicians: An Outer View of the Inner World [4]

A group is a set G together with a binary operation on G, here denoted ⋅, that combines any two elements a and b to form an element of G, denoted a ⋅ b, in a way such that the following three requirements, known as group axioms, are satisfied:[5][6][7]

- Associativity

- For all a, b, c in G, one has (a ⋅ b) ⋅ c = a ⋅ (b ⋅ c).

- Identity element

- There exists an element e in G such that, for every a in G, one has e ⋅ a = a and a ⋅ e = a. Such an element is unique (see below). It is called the identity element of the group.

- Inverse element

- For each a in G, there exists an element b in G such that a ⋅ b = e and b ⋅ a = e, where e is the identity element. For each a, the element b is unique (see below); it is called the inverse of a and is commonly denoted a−1.

Notation and terminology

Formally, the group is the ordered pair of a set and a binary operation on this set that satisfies the group axioms. The set is called the underlying set of the group, and the operation is called the group operation or the group law.

A group and its underlying set are thus two different mathematical objects. But to avoid cumbersome notation, it is common to abuse notation by using the same symbol to denote both. This reflects also an informal way of thinking, that the group is the same as the set except that it has been enriched by additional structure provided by the operation.

For example, consider the set of real numbers , which has the operations of addition and multiplication . Formally, is a set, is a group, and is a field. But it is common to write to denote any of these three objects.

The additive group of the field is the group whose underlying set is and whose operation is addition. The multiplicative group of the field is the group whose underlying set is the set of nonzero real numbers and whose operation is multiplication.

More generally, one speaks of an additive group whenever the group operation is notated as addition; in this case, the identity is typically denoted 0,[8] and the inverse of an element x is denoted –x. Similarly, one speaks of a multiplicative group whenever the group operation is notated as multiplication; in this case, the identity is typically denoted 1, and the inverse of an element x is denoted x–1. In a multiplicative group, the operation symbol is usually omitted entirely, so that the operation is denoted by juxtaposition, ab instead of a ⋅ b.

The definition of a group does not require that a ⋅ b = b ⋅ a for all elements a and b in G. If this additional condition holds, then the operation is said to be commutative, and the group is called an abelian group. It is a common convention that for an abelian group either additive or multiplicative notation may be used, but for a nonabelian group only multiplicative notation is used.

Several other notations are commonly used for groups whose elements are not numbers. For a group whose elements are functions, the operation is often function composition ; then the identity may be denoted id. In the more specific cases of geometric transformation groups, symmetry groups, permutation groups, and automorphism groups, the symbol is often omitted, as for multiplicative groups. Many other variants of notation may be encountered.

Alternative definition

An equivalent definition of group consists of replacing the "there exist" part of the group axioms by operations whose result is the element that must exist. So, a group is a set equipped with three operations, a binary operation, which is the group operation, a unary operation, which provides the inverse of its single operand, and a nullary operation, which has no operand and results in the identity element. Otherwise, the group axioms are exactly the same.

This variant of the definition avoids existential quantifiers. It is generally preferred for computing with groups and for computer-aided proofs. This formulation exhibits groups as a variety of universal algebra. It is also useful for talking of properties of the inverse operation, as needed for defining topological groups and group objects.

Second example: a symmetry group

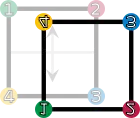

Two figures in the plane are congruent if one can be changed into the other using a combination of rotations, reflections, and translations. Any figure is congruent to itself. However, some figures are congruent to themselves in more than one way, and these extra congruences are called symmetries. A square has eight symmetries. These are:

id (keeping it as it is) |  r1 (rotation by 90° clockwise) |  r2 (rotation by 180°) |  r3 (rotation by 270° clockwise) |

fv (vertical reflection) |  fh (horizontal reflection) |  fd (diagonal reflection) |  fc (counter-diagonal reflection) |

- the identity operation leaving everything unchanged, denoted id;

- rotations of the square around its center by 90°, 180°, and 270° clockwise, denoted by r1, r2 and r3, respectively;

- reflections about the horizontal and vertical middle line (fv and fh), or through the two diagonals (fd and fc).

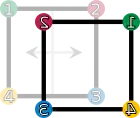

These symmetries are functions. Each sends a point in the square to the corresponding point under the symmetry. For example, r1 sends a point to its rotation 90° clockwise around the square's center, and fh sends a point to its reflection across the square's vertical middle line. Composing two of these symmetries gives another symmetry. These symmetries determine a group called the dihedral group of degree 4, denoted D4. The underlying set of the group is the above set of symmetries, and the group operation is function composition.[9] Two symmetries are combined by composing them as functions, that is, applying the first one to the square, and the second one to the result of the first application. The result of performing first a and then b is written symbolically from right to left as ("apply the symmetry b after performing the symmetry a"). (This is the usual notation for composition of functions.)

The group table on the right lists the results of all such compositions possible. For example, rotating by 270° clockwise (r3) and then reflecting horizontally (fh) is the same as performing a reflection along the diagonal (fd). Using the above symbols, highlighted in blue in the group table:

| id | r1 | r2 | r3 | fv | fh | fd | fc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| id | id | r1 | r2 | r3 | fv | fh | fd | fc |

| r1 | r1 | r2 | r3 | id | fc | fd | fv | fh |

| r2 | r2 | r3 | id | r1 | fh | fv | fc | fd |

| r3 | r3 | id | r1 | r2 | fd | fc | fh | fv |

| fv | fv | fd | fh | fc | id | r2 | r1 | r3 |

| fh | fh | fc | fv | fd | r2 | id | r3 | r1 |

| fd | fd | fh | fc | fv | r3 | r1 | id | r2 |

| fc | fc | fv | fd | fh | r1 | r3 | r2 | id |

| The elements id, r1, r2, and r3 form a subgroup whose group table is highlighted in red (upper left region). A left and right coset of this subgroup is highlighted in green (in the last row) and yellow (last column), respectively. | ||||||||

Given this set of symmetries and the described operation, the group axioms can be understood as follows.

Composition is a binary operation. That is, is a symmetry for any two symmetries a and b. For example,

that is, rotating 270° clockwise after reflecting horizontally equals reflecting along the counter-diagonal (fc). Indeed every other combination of two symmetries still gives a symmetry, as can be checked using the group table.

The associativity axiom deals with composing more than two symmetries: Starting with three elements a, b and c of D4, there are two possible ways of using these three symmetries in this order to determine a symmetry of the square. One of these ways is to first compose a and b into a single symmetry, then to compose that symmetry with c. The other way is to first compose b and c, then to compose the resulting symmetry with a. These two ways must give always the same result, that is,

For example, can be checked using the group table at the right:

The identity element is id, as, it does not changes any symmetry a when composed with it either on the left or on the right.

All symmetries have an inverse: id, the reflections fh, fv, fd, fc and the 180° rotation r2 are their own inverse, because performing them twice brings the square back to its original orientation. The rotations r3 and r1 are each other's inverses, because rotating 90° and then rotation 270° (or vice versa) yields a rotation over 360° which leaves the square unchanged. This is easily verified on the table.

In contrast to the group of integers above, where the order of the operation is irrelevant, it does matter in D4, as, for example, but In other words, D4 is not abelian.

History

The modern concept of an abstract group developed out of several fields of mathematics.[10][11][12] The original motivation for group theory was the quest for solutions of polynomial equations of degree higher than 4. The 19th-century French mathematician Évariste Galois, extending prior work of Paolo Ruffini and Joseph-Louis Lagrange, gave a criterion for the solvability of a particular polynomial equation in terms of the symmetry group of its roots (solutions). The elements of such a Galois group correspond to certain permutations of the roots. At first, Galois' ideas were rejected by his contemporaries, and published only posthumously.[13][14] More general permutation groups were investigated in particular by Augustin Louis Cauchy. Arthur Cayley's On the theory of groups, as depending on the symbolic equation θn = 1 (1854) gives the first abstract definition of a finite group.[15]

Geometry was a second field in which groups were used systematically, especially symmetry groups as part of Felix Klein's 1872 Erlangen program.[16] After novel geometries such as hyperbolic and projective geometry had emerged, Klein used group theory to organize them in a more coherent way. Further advancing these ideas, Sophus Lie founded the study of Lie groups in 1884.[17]

The third field contributing to group theory was number theory. Certain abelian group structures had been used implicitly in Carl Friedrich Gauss' number-theoretical work Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (1798), and more explicitly by Leopold Kronecker.[18] In 1847, Ernst Kummer made early attempts to prove Fermat's Last Theorem by developing groups describing factorization into prime numbers.[19]

The convergence of these various sources into a uniform theory of groups started with Camille Jordan's Traité des substitutions et des équations algébriques (1870).[20] Walther von Dyck (1882) introduced the idea of specifying a group by means of generators and relations, and was also the first to give an axiomatic definition of an "abstract group", in the terminology of the time.[21] As of the 20th century, groups gained wide recognition by the pioneering work of Ferdinand Georg Frobenius and William Burnside, who worked on representation theory of finite groups, Richard Brauer's modular representation theory and Issai Schur's papers.[22] The theory of Lie groups, and more generally locally compact groups was studied by Hermann Weyl, Élie Cartan and many others.[23] Its algebraic counterpart, the theory of algebraic groups, was first shaped by Claude Chevalley (from the late 1930s) and later by the work of Armand Borel and Jacques Tits.[24]

The University of Chicago's 1960–61 Group Theory Year brought together group theorists such as Daniel Gorenstein, John G. Thompson and Walter Feit, laying the foundation of a collaboration that, with input from numerous other mathematicians, led to the classification of finite simple groups, with the final step taken by Aschbacher and Smith in 2004. This project exceeded previous mathematical endeavours by its sheer size, in both length of proof and number of researchers. Research is ongoing to simplify the proof of this classification.[25] These days, group theory is still a highly active mathematical branch, impacting many other fields.[a]

Elementary consequences of the group axioms

Basic facts about all groups that can be obtained directly from the group axioms are commonly subsumed under elementary group theory.[26] For example, repeated applications of the associativity axiom show that the unambiguity of

- a ⋅ b ⋅ c = (a ⋅ b) ⋅ c = a ⋅ (b ⋅ c)

generalizes to more than three factors. Because this implies that parentheses can be inserted anywhere within such a series of terms, parentheses are usually omitted.[27]

The axioms may be weakened to assert only the existence of a left identity and left inverses. Both can be shown to be actually two-sided, so the resulting definition is equivalent to the one given above.[28]

Uniqueness of identity element

The group axioms imply that the identity element is unique: If e and f are identity elements of a group, then e = e ⋅ f = f. Therefore it is customary to speak of the identity.[29]

Uniqueness of inverses

The group axioms also imply that the inverse of each element is unique: If a group element a has both b and c as inverses, then

b = b ⋅ e since e is the identity element = b ⋅ (a ⋅ c) since c is an inverse of a, so e = a ⋅ c = (b ⋅ a) ⋅ c by associativity, which allows rearranging the parentheses = e ⋅ c since b is an inverse of a, so b ⋅ a = e = c since e is the identity element.

Therefore it is customary to speak of the inverse of an element.[29]

Division

Given elements a and b of a group G, there is a unique solution x in G to the equation a ⋅ x = b, namely a−1 ⋅ b. (One usually avoids using notations such as or b/a, unless G is abelian, because of the ambiguity of whether they mean a−1 ⋅ b or b ⋅ a−1.)[30] It follows that for each a in G, the function G → G given by x ↦ a ⋅ x is a bijection; it is called left multiplication by a or left translation by a.

Similarly, given a and b, the unique solution to x ⋅ a = b is b ⋅ a−1. For each a, the function G → G given by x ↦ x ⋅ a is a bijection called right multiplication by a or right translation by a.

Basic concepts

When studying sets, one uses concepts such as subset, function, and quotient by an equivalence relation. When studying groups, one uses their analogues: subgroup, homomorphism, and quotient group, respectively. These are explained below.

Group homomorphisms

Group homomorphisms[g] are functions that respect group structure; they may be used to relate two groups. A homomorphism from a group (G, ⋅) to a group (H, ∗) is a function φ: G → H such that

- φ(a ⋅ b) = φ(a) ∗ φ(b) for all elements a, b in G.

It would be natural to require also that φ(1G) = 1H and φ(a–1) = φ(a)–1 for all a in G, but this is not necessary, because these conditions are already implied by the definition above.[31]

The identity homomorphism of a group G is the homomorphism idG: G → G defined by g ↦ g. An inverse homomorphism of a homomorphism φ: G → H is a homomorphism Φ: H → G such that Φ ∘ φ = idG and φ ∘ Φ = idH, i.e., such that Φ(φ(g)) = g for all g in G and φ(Φ(h)) = h for all h in H. An isomorphism is a homomorphism that has an inverse homomorphism; equivalently, it is a bijective homomorphism. Groups G and H are called isomorphic if there exists an isomorphism φ: G → H; in this case, H can be obtained from G simply by renaming its elements according to the function φ; then any statement true for G is true for H, provided that any specific elements mentioned in the statement are also renamed.

Subgroups

Informally, a subgroup is a group H contained within a bigger one, G.[32] Concretely, the identity element of G is contained in H, and whenever h1 and h2 are in H, then so are h1 ⋅ h2 and h1−1, so the elements of H, equipped with the group operation on G restricted to H, indeed form a group.

In the example above, the identity and the rotations constitute a subgroup R = {id, r1, r2, r3}, highlighted in red in the group table above: any two rotations composed are still a rotation, and a rotation can be undone by (i.e., is inverse to) the complementary rotations 270° for 90°, 180° for 180°, and 90° for 270° (note that rotation in the opposite direction is not defined). The subgroup test is a necessary and sufficient condition for a nonempty subset H of a group G to be a subgroup: it is sufficient to check that g−1h ∈ H for all elements g, h ∈ H. Knowing the subgroups is important in understanding the group as a whole.[d]

Given any subset S of a group G, the subgroup generated by S consists of products of elements of S and their inverses. It is the smallest subgroup of G containing S.[33] In the introductory example above, the subgroup generated by r2 and fv consists of these two elements, the identity element id and fh = fv ⋅ r2. Again, this is a subgroup, because combining any two of these four elements or their inverses (which are, in this particular case, these same elements) yields an element of this subgroup.

Cosets

In many situations it is desirable to consider two group elements the same if they differ by an element of a given subgroup. For example, in D4 above, once a reflection is performed, the square never gets back to the r2 configuration by just applying the rotation operations (and no further reflections), i.e., the rotation operations are irrelevant to the question whether a reflection has been performed. Cosets are used to formalize this insight: a subgroup H defines left and right cosets, which can be thought of as translations of H by arbitrary group elements g. In symbolic terms, the left and right cosets of H containing g are

- gH = {g ⋅ h : h ∈ H} and Hg = {h ⋅ g : h ∈ H}, respectively.[34]

The left cosets of any subgroup H form a partition of G; that is, the union of all left cosets is equal to G and two left cosets are either equal or have an empty intersection.[35] The first case g1H = g2H happens precisely when g1−1 ⋅ g2 ∈ H, i.e., if the two elements differ by an element of H. Similar considerations apply to the right cosets of H. The left and right cosets of H may or may not be equal. If they are, i.e., for all g in G, gH = Hg, then H is said to be a normal subgroup.

In D4, the introductory symmetry group, the left cosets gR of the subgroup R consisting of the rotations are either equal to R, if g is an element of R itself, or otherwise equal to U = fcR = {fc, fv, fd, fh} (highlighted in green). The subgroup R is also normal, because fcR = U = Rfc and similarly for any element other than fc. (In fact, in the case of D4, observe that all such cosets are equal, such that fhR = fvR = fdR = fcR.)

Quotient groups

In some situations the set of cosets of a subgroup can be endowed with a group law, giving a quotient group or factor group. For this to be possible, the subgroup has to be normal. Given any normal subgroup N, the quotient group is defined by

- G / N = {gN, g ∈ G}, "G modulo N".[36]

This set inherits a group operation (sometimes called coset multiplication, or coset addition) from the original group G: (gN) ⋅ (hN) = (gh)N for all g and h in G. This definition is motivated by the idea (itself an instance of general structural considerations outlined above) that the map G → G / N that associates to any element g its coset gN be a group homomorphism, or by general abstract considerations called universal properties. The coset eN = N serves as the identity in this group, and the inverse of gN in the quotient group is (gN)−1 = (g−1)N.[e]

| ⋅ | R | U |

|---|---|---|

| R | R | U |

| U | U | R |

The elements of the quotient group D4 / R are R itself, which represents the identity, and U = fvR. The group operation on the quotient is shown at the right. For example, U ⋅ U = fvR ⋅ fvR = (fv ⋅ fv)R = R. Both the subgroup R = {id, r1, r2, r3}, as well as the corresponding quotient are abelian, whereas D4 is not abelian. Building bigger groups by smaller ones, such as D4 from its subgroup R and the quotient D4 / R is abstracted by a notion called semidirect product.

Quotient groups and subgroups together form a way of describing every group by its presentation: any group is the quotient of the free group over the generators of the group, quotiented by the subgroup of relations. The dihedral group D4, for example, can be generated by two elements r and f (for example, r = r1, the right rotation and f = fv the vertical (or any other) reflection), which means that every symmetry of the square is a finite composition of these two symmetries or their inverses. Together with the relations

- r 4 = f 2 = (r ⋅ f)2 = 1,[37]

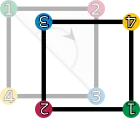

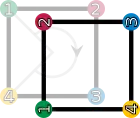

the group is completely described. A presentation of a group can also be used to construct the Cayley graph, a device used to graphically capture discrete groups.

Sub- and quotient groups are related in the following way: a subset H of G can be seen as an injective map H → G, i.e., any element of the target has at most one element that maps to it. The counterpart to injective maps are surjective maps (every element of the target is mapped onto), such as the canonical map G → G / N.[y] Interpreting subgroup and quotients in light of these homomorphisms emphasizes the structural concept inherent to these definitions alluded to in the introduction. In general, homomorphisms are neither injective nor surjective. Kernel and image of group homomorphisms and the first isomorphism theorem address this phenomenon.

Examples and applications

Examples and applications of groups abound. A starting point is the group Z of integers with addition as group operation, introduced above. If instead of addition multiplication is considered, one obtains multiplicative groups. These groups are predecessors of important constructions in abstract algebra.

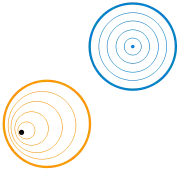

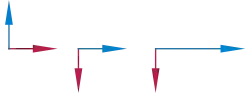

Groups are also applied in many other mathematical areas. Mathematical objects are often examined by associating groups to them and studying the properties of the corresponding groups. For example, Henri Poincaré founded what is now called algebraic topology by introducing the fundamental group.[38] By means of this connection, topological properties such as proximity and continuity translate into properties of groups.[i] For example, elements of the fundamental group are represented by loops. The second image at the right shows some loops in a plane minus a point. The blue loop is considered null-homotopic (and thus irrelevant), because it can be continuously shrunk to a point. The presence of the hole prevents the orange loop from being shrunk to a point. The fundamental group of the plane with a point deleted turns out to be infinite cyclic, generated by the orange loop (or any other loop winding once around the hole). This way, the fundamental group detects the hole.

In more recent applications, the influence has also been reversed to motivate geometric constructions by a group-theoretical background.[j] In a similar vein, geometric group theory employs geometric concepts, for example in the study of hyperbolic groups.[39] Further branches crucially applying groups include algebraic geometry and number theory.[40]

In addition to the above theoretical applications, many practical applications of groups exist. Cryptography relies on the combination of the abstract group theory approach together with algorithmical knowledge obtained in computational group theory, in particular when implemented for finite groups.[41] Applications of group theory are not restricted to mathematics; sciences such as physics, chemistry and computer science benefit from the concept.

Numbers

Many number systems, such as the integers and the rationals enjoy a naturally given group structure. In some cases, such as with the rationals, both addition and multiplication operations give rise to group structures. Such number systems are predecessors to more general algebraic structures known as rings and fields. Further abstract algebraic concepts such as modules, vector spaces and algebras also form groups.

Integers

The group of integers under addition, denoted , has been described above. The integers, with the operation of multiplication instead of addition, do not form a group. The associativity and identity axioms are satisfied, but inverses do not exist: for example, a = 2 is an integer, but the only solution to the equation a · b = 1 in this case is b = 1/2, which is a rational number, but not an integer. Hence not every element of has a (multiplicative) inverse.[k]

Rationals

The desire for the existence of multiplicative inverses suggests considering fractions

Fractions of integers (with b nonzero) are known as rational numbers.[l] The set of all such irreducible fractions is commonly denoted . There is still a minor obstacle for , the rationals with multiplication, being a group: because the rational number 0 does not have a multiplicative inverse (i.e., there is no x such that x · 0 = 1), is still not a group.

However, the set of all nonzero rational numbers does form an abelian group under multiplication, generally denoted .[m] Associativity and identity element axioms follow from the properties of integers. The closure requirement still holds true after removing zero, because the product of two nonzero rationals is never zero. Finally, the inverse of a/b is b/a, therefore the axiom of the inverse element is satisfied.

The rational numbers (including 0) also form a group under addition. Intertwining addition and multiplication operations yields more complicated structures called rings and—if division is possible, such as in —fields, which occupy a central position in abstract algebra. Group theoretic arguments therefore underlie parts of the theory of those entities.[n]

Modular arithmetic

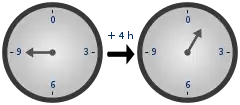

In modular arithmetic, two integers are added and then the sum is divided by a positive integer called the modulus. The result of modular addition is the remainder of that division. For any modulus, n, the set of integers from 0 to n − 1 forms a group under modular addition: the inverse of any element a is n − a, and 0 is the identity element. This is familiar from the addition of hours on the face of a clock: if the hour hand is on 9 and is advanced 4 hours, it ends up on 1, as shown at the right. This is expressed by saying that 9 + 4 equals 1 "modulo 12" or, in symbols,

- 9 + 4 ≡ 1 modulo 12.

The group of integers modulo n is written or .

For any prime number p, there is also the multiplicative group of integers modulo p.[42] Its elements are the integers 1 to p − 1. The group operation is multiplication modulo p. That is, the usual product is divided by p and the remainder of this division is the result of modular multiplication. For example, if p = 5, there are four group elements 1, 2, 3, 4. In this group, 4 · 4 = 1, because the usual product 16 is equivalent to 1, which divided by 5 yields a remainder of 1. for 5 divides 16 − 1 = 15, denoted

- 16 ≡ 1 (mod 5).

The primality of p ensures that the product of two integers neither of which is divisible by p is not divisible by p either, hence the indicated set of classes is closed under multiplication.[o] The identity element is 1, as usual for a multiplicative group, and the associativity follows from the corresponding property of integers. Finally, the inverse element axiom requires that given an integer a not divisible by p, there exists an integer b such that

- a · b ≡ 1 (mod p), i.e., p divides the difference a · b − 1.

The inverse b can be found by using Bézout's identity and the fact that the greatest common divisor gcd(a, p) equals 1.[43] In the case p = 5 above, the inverse of 4 is 4, and the inverse of 3 is 2, as 3 · 2 = 6 ≡ 1 (mod 5). Hence all group axioms are fulfilled. Actually, this example is similar to above: it consists of exactly those elements in that have a multiplicative inverse.[44] These groups are denoted Fp×. They are crucial to public-key cryptography.[p]

Cyclic groups

A cyclic group is a group all of whose elements are powers of a particular element a.[45] In multiplicative notation, the elements of the group are:

- ..., a−3, a−2, a−1, a0 = e, a, a2, a3, ...,

where a2 means a ⋅ a, and a−3 stands for a−1 ⋅ a−1 ⋅ a−1 = (a ⋅ a ⋅ a)−1 etc.[h] Such an element a is called a generator or a primitive element of the group. In additive notation, the requirement for an element to be primitive is that each element of the group can be written as

- ..., −a−a, −a, 0, a, a+a, ...

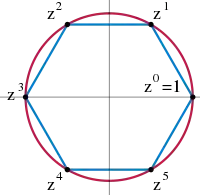

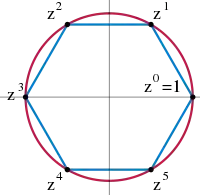

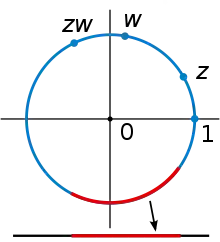

In the groups Z/nZ introduced above, the element 1 is primitive, so these groups are cyclic. Indeed, each element is expressible as a sum all of whose terms are 1. Any cyclic group with n elements is isomorphic to this group. A second example for cyclic groups is the group of n-th complex roots of unity, given by complex numbers z satisfying zn = 1. These numbers can be visualized as the vertices on a regular n-gon, as shown in blue at the right for n = 6. The group operation is multiplication of complex numbers. In the picture, multiplying with z corresponds to a counter-clockwise rotation by 60°.[46] Using some field theory, the group Fp× can be shown to be cyclic: for example, if p = 5, 3 is a generator since 31 = 3, 32 = 9 ≡ 4, 33 ≡ 2, and 34 ≡ 1.

Some cyclic groups have an infinite number of elements. In these groups, for every non-zero element a, all the powers of a are distinct; despite the name "cyclic group", the powers of the elements do not cycle. An infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to (Z, +), the group of integers under addition introduced above.[47] As these two prototypes are both abelian, so is any cyclic group.

The study of finitely generated abelian groups is quite mature, including the fundamental theorem of finitely generated abelian groups; and reflecting this state of affairs, many group-related notions, such as center and commutator, describe the extent to which a given group is not abelian.[48]

Symmetry groups

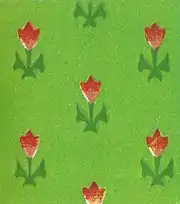

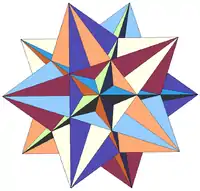

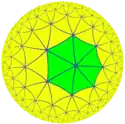

Symmetry groups are groups consisting of symmetries of given mathematical objects—be they of geometric nature, such as the introductory symmetry group of the square, or of algebraic nature, such as polynomial equations and their solutions.[49] Conceptually, group theory can be thought of as the study of symmetry.[t] Symmetries in mathematics greatly simplify the study of geometrical or analytical objects. A group is said to act on another mathematical object X if every group element can be associated to some operation on X and the composition of these operations follows the group law. In the rightmost example below, an element of order 7 of the (2,3,7) triangle group acts on the tiling by permuting the highlighted warped triangles (and the other ones, too). By a group action, the group pattern is connected to the structure of the object being acted on.

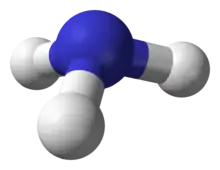

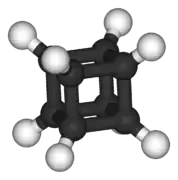

In chemical fields, such as crystallography, space groups and point groups describe molecular symmetries and crystal symmetries. These symmetries underlie the chemical and physical behavior of these systems, and group theory enables simplification of quantum mechanical analysis of these properties.[50] For example, group theory is used to show that optical transitions between certain quantum levels cannot occur simply because of the symmetry of the states involved.

Not only are groups useful to assess the implications of symmetries in molecules, but surprisingly they also predict that molecules sometimes can change symmetry. The Jahn-Teller effect is a distortion of a molecule of high symmetry when it adopts a particular ground state of lower symmetry from a set of possible ground states that are related to each other by the symmetry operations of the molecule.[51][52]

Likewise, group theory helps predict the changes in physical properties that occur when a material undergoes a phase transition, for example, from a cubic to a tetrahedral crystalline form. An example is ferroelectric materials, where the change from a paraelectric to a ferroelectric state occurs at the Curie temperature and is related to a change from the high-symmetry paraelectric state to the lower symmetry ferroelectric state, accompanied by a so-called soft phonon mode, a vibrational lattice mode that goes to zero frequency at the transition.[53]

Such spontaneous symmetry breaking has found further application in elementary particle physics, where its occurrence is related to the appearance of Goldstone bosons.

|

|

|

-3D-balls.png.webp) |

|

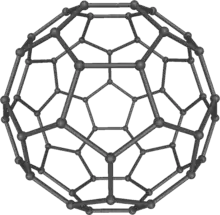

| Buckminsterfullerene displays icosahedral symmetry, though the double bonds reduce this to pyritohedral symmetry. |

Ammonia, NH3. Its symmetry group is of order 6, generated by a 120° rotation and a reflection. | Cubane C8H8 features octahedral symmetry. |

Hexaaquacopper(II) complex ion, [Cu(OH2)6]2+. Compared to a perfectly symmetrical shape, the molecule is vertically dilated by about 22% (Jahn-Teller effect). | The (2,3,7) triangle group, a hyperbolic group, acts on this tiling of the hyperbolic plane. |

Finite symmetry groups such as the Mathieu groups are used in coding theory, which is in turn applied in error correction of transmitted data, and in CD players.[54] Another application is differential Galois theory, which characterizes functions having antiderivatives of a prescribed form, giving group-theoretic criteria for when solutions of certain differential equations are well-behaved.[u] Geometric properties that remain stable under group actions are investigated in (geometric) invariant theory.[55]

General linear group and representation theory

Matrix groups consist of matrices together with matrix multiplication. The general linear group GL(n, R) consists of all invertible n-by-n matrices with real entries.[56] Its subgroups are referred to as matrix groups or linear groups. The dihedral group example mentioned above can be viewed as a (very small) matrix group. Another important matrix group is the special orthogonal group SO(n). It describes all possible rotations in n dimensions. Via Euler angles, rotation matrices are used in computer graphics.[57]

Representation theory is both an application of the group concept and important for a deeper understanding of groups.[58][59] It studies the group by its group actions on other spaces. A broad class of group representations are linear representations, i.e., the group is acting on a vector space, such as the three-dimensional Euclidean space R3. A representation of G on an n-dimensional real vector space is simply a group homomorphism

- ρ: G → GL(n, R)

from the group to the general linear group. This way, the group operation, which may be abstractly given, translates to the multiplication of matrices making it accessible to explicit computations.[w]

Given a group action, this gives further means to study the object being acted on.[x] On the other hand, it also yields information about the group. Group representations are an organizing principle in the theory of finite groups, Lie groups, algebraic groups and topological groups, especially (locally) compact groups.[58][60]

Galois groups

Galois groups were developed to help solve polynomial equations by capturing their symmetry features.[61][62] For example, the solutions of the quadratic equation ax2 + bx + c = 0 are given by

Exchanging "+" and "−" in the expression, i.e., permuting the two solutions of the equation can be viewed as a (very simple) group operation. Similar formulae are known for cubic and quartic equations, but do not exist in general for degree 5 and higher.[63] Abstract properties of Galois groups associated with polynomials (in particular their solvability) give a criterion for polynomials that have all their solutions expressible by radicals, i.e., solutions expressible using solely addition, multiplication, and roots similar to the formula above.[64]

The problem can be dealt with by shifting to field theory and considering the splitting field of a polynomial. Modern Galois theory generalizes the above type of Galois groups to field extensions and establishes—via the fundamental theorem of Galois theory—a precise relationship between fields and groups, underlining once again the ubiquity of groups in mathematics.

Finite groups

A group is called finite if it has a finite number of elements. The number of elements is called the order of the group.[65] An important class is the symmetric groups SN, the groups of permutations of N objects. For example, the symmetric group on 3 letters S3 is the group of all possible reorderings of the objects. For example, the three letters ABC, can be reordered into ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, CBA, forming in total 6 (factorial of 3) elements. The operation is the composition of the reorderings. The neutral element is keeping the ordering the same. This class is fundamental insofar as any finite group can be expressed as a subgroup of a symmetric group SN for a suitable integer N, according to Cayley's theorem. Parallel to the group of symmetries of the square above, S3 can also be interpreted as the group of symmetries of an equilateral triangle.

The order of an element a in a group G is the least positive integer n such that an = e, where an represents

that is, application of the operation "⋅" to n copies of a. (If "⋅" represents multiplication, then an corresponds to the nth power of a.) In infinite groups, such an n may not exist, in which case the order of a is said to be infinity. The order of an element equals the order of the cyclic subgroup generated by this element.

More sophisticated counting techniques, for example, counting cosets, yield more precise statements about finite groups: Lagrange's Theorem states that for a finite group G the order of any finite subgroup H divides the order of G. The Sylow theorems give a partial converse.

The dihedral group (discussed above) is a finite group of order 8. The order of r1 is 4, as is the order of the subgroup R it generates (see above). The order of the reflection elements fv etc. is 2. Both orders divide 8, as predicted by Lagrange's theorem. The groups Fp× above have order p − 1.

Classification of finite simple groups

Mathematicians often strive for a complete classification (or list) of a mathematical notion. In the context of finite groups, this aim leads to difficult mathematics. According to Lagrange's theorem, finite groups of order p, a prime number, are necessarily cyclic (abelian) groups Zp. Groups of order p2 can also be shown to be abelian, a statement which does not generalize to order p3, as the non-abelian group D4 of order 8 = 23 above shows.[66] Computer algebra systems can be used to list small groups, but there is no classification of all finite groups.[q] An intermediate step is the classification of finite simple groups.[r] A nontrivial group is called simple if its only normal subgroups are the trivial group and the group itself.[s] The Jordan–Hölder theorem exhibits finite simple groups as the building blocks for all finite groups.[67] Listing all finite simple groups was a major achievement in contemporary group theory. 1998 Fields Medal winner Richard Borcherds succeeded in proving the monstrous moonshine conjectures, a surprising and deep relation between the largest finite simple sporadic group (the "monster group") and certain modular functions, a piece of classical complex analysis, and string theory, a theory supposed to unify the description of many physical phenomena.[68]

The category of groups

If one considers all groups at once, and all the homomorphisms between them, one gets a category.[69] In fact, the category of groups is one of the motivating examples for the definition of category; the axioms in the definition of category reflect properties of group homomorphisms, such as the fact that homomorphisms A → B and B → C can be composed to produce a homomorphism A → C.

There is no cardinal number that bounds the cardinality of every group, so there cannot be a set whose members are all the groups; instead the collection of all groups is a proper class. This means that the category of groups is not a small category. On the other hand, given groups G and H, the collection Hom(G,H) of all homomorphisms G → H is a set (it may be viewed as a subset of the power set of G × H), so the category of groups is a locally small category.

Groups with additional structure

Many groups are simultaneously groups and examples of other mathematical structures. In the language of category theory, they are group objects in a category, meaning that they are objects (that is, examples of another mathematical structure) which come with transformations (called morphisms) that mimic the group axioms. For example, every group (as defined above) is also a set, so a group is a group object in the category of sets.

Topological groups

Some topological spaces may be endowed with a group law. In order for the group law and the topology to interweave well, the group operations must be continuous functions; informally, g ⋅ h and g−1 must not vary wildly if g and h vary only a little. Such groups are called topological groups, and they are the group objects in the category of topological spaces.[70] The most basic examples are the group of real numbers under addition and the group of nonzero real numbers under multiplication. Similar examples can be formed from any other topological field, such as the field of complex numbers or the field of p-adic numbers. These examples are locally compact, so they have Haar measures and can be studied via harmonic analysis. Other locally compact topological groups include the group of points of an algebraic group over a local field or adele ring; these are basic to number theory.[71] Galois groups of infinite algebraic field extensions are equipped with the Krull topology, which plays a role in infinite Galois theory.[72] A generalization used in algebraic geometry is the étale fundamental group.[73]

Lie groups

A Lie group is a group that also has the structure of a differentiable manifold; informally, this means that it looks locally like a Euclidean space of some fixed dimension.[74] Again, the definition requires the additional structure, here the manifold structure, to be compatible: the multiplication and inverse maps are required to be smooth.

A standard example is the general linear group introduced above: it is an open subset of the space of all n-by-n matrices, because it is given by the inequality

- det (A) ≠ 0,

where A denotes an n-by-n matrix.[75]

Lie groups are of fundamental importance in modern physics: Noether's theorem links continuous symmetries to conserved quantities.[76] Rotation, as well as translations in space and time are basic symmetries of the laws of mechanics. They can, for instance, be used to construct simple models—imposing, say, axial symmetry on a situation will typically lead to significant simplification in the equations one needs to solve to provide a physical description.[v] Another example is the group of Lorentz transformations, which relate measurements of time and velocity of two observers in motion relative to each other. They can be deduced in a purely group-theoretical way, by expressing the transformations as a rotational symmetry of Minkowski space. The latter serves—in the absence of significant gravitation—as a model of spacetime in special relativity.[77] The full symmetry group of Minkowski space, i.e., including translations, is known as the Poincaré group. By the above, it plays a pivotal role in special relativity and, by implication, for quantum field theories.[78] Symmetries that vary with location are central to the modern description of physical interactions with the help of gauge theory.[79]

Generalizations

| Group-like structures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalityα | Associativity | Identity | Invertibility | Commutativity | |

| Semigroupoid | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Small Category | Unneeded | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Groupoid | Unneeded | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded |

| Magma | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Quasigroup | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded |

| Unital Magma | Required | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Loop | Required | Unneeded | Required | Required | Unneeded |

| Semigroup | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Inverse Semigroup | Required | Required | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded |

| Monoid | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Commutative monoid | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded | Required |

| Group | Required | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded |

| Abelian group | Required | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| ^α Closure, which is used in many sources, is an equivalent axiom to totality, though defined differently. | |||||

In abstract algebra, more general structures are defined by relaxing some of the axioms defining a group.[69][80][81] For example, if the requirement that every element has an inverse is eliminated, the resulting algebraic structure is called a monoid. The natural numbers N (including 0) under addition form a monoid, as do the nonzero integers under multiplication (Z ∖ {0}, ·), see above. There is a general method to formally add inverses to elements to any (abelian) monoid, much the same way as (Q ∖ {0}, ·) is derived from (Z ∖ {0}, ·), known as the Grothendieck group. Groupoids are similar to groups except that the composition a ⋅ b need not be defined for all a and b. They arise in the study of more complicated forms of symmetry, often in topological and analytical structures, such as the fundamental groupoid or stacks. Finally, it is possible to generalize any of these concepts by replacing the binary operation with an arbitrary n-ary one (i.e., an operation taking n arguments). With the proper generalization of the group axioms this gives rise to an n-ary group.[82] The table gives a list of several structures generalizing groups.

See also

Notes

^ a: Mathematical Reviews lists 3,224 research papers on group theory and its generalizations written in 2005.

^ aa: The classification was announced in 1983, but gaps were found in the proof. See classification of finite simple groups for further information.

^ b: The closure axiom is already implied by the condition that ⋅ be a binary operation. Some authors therefore omit this axiom. However, group constructions often start with an operation defined on a superset, so a closure step is common in proofs that a system is a group. Lang 2002

^ c: See, for example, the books of Lang (2002, 2005) and Herstein (1996, 1975).

^ d: However, a group is not determined by its lattice of subgroups. See Suzuki 1951.

^ e: The fact that the group operation extends this canonically is an instance of a universal property.

^ f: For example, if G is finite, then the size of any subgroup and any quotient group divides the size of G, according to Lagrange's theorem.

^ g: The word homomorphism derives from Greek ὁμός—the same and μορφή—structure.

^ h: The additive notation for elements of a cyclic group would be t ⋅ a, t in Z.

^ i: See the Seifert–Van Kampen theorem for an example.

^ j: An example is group cohomology of a group which equals the singular cohomology of its classifying space.

^ k: Elements which do have multiplicative inverses are called units, see Lang 2002, §II.1, p. 84.

^ l: The transition from the integers to the rationals by adding fractions is generalized by the field of fractions.

^ m: The same is true for any field F instead of Q. See Lang 2005, §III.1, p. 86.

^ n: For example, a finite subgroup of the multiplicative group of a field is necessarily cyclic. See Lang 2002, Theorem IV.1.9. The notions of torsion of a module and simple algebras are other instances of this principle.

^ o: The stated property is a possible definition of prime numbers. See prime element.

^ p: For example, the Diffie-Hellman protocol uses the discrete logarithm.

^ q: The groups of order at most 2000 are known. Up to isomorphism, there are about 49 billion. See Besche, Eick & O'Brien 2001.

^ r: The gap between the classification of simple groups and the one of all groups lies in the extension problem, a problem too hard to be solved in general. See Aschbacher 2004, p. 737.

^ s: Equivalently, a nontrivial group is simple if its only quotient groups are the trivial group and the group itself. See Michler 2006, Carter 1989.

^ t: More rigorously, every group is the symmetry group of some graph; see Frucht's theorem, Frucht 1939.

^ u: More precisely, the monodromy action on the vector space of solutions of the differential equations is considered. See Kuga 1993, pp. 105–113.

^ v: See Schwarzschild metric for an example where symmetry greatly reduces the complexity of physical systems.

^ w: This was crucial to the classification of finite simple groups, for example. See Aschbacher 2004.

^ x: See, for example, Schur's Lemma for the impact of a group action on simple modules. A more involved example is the action of an absolute Galois group on étale cohomology.

^ y: Injective and surjective maps correspond to mono- and epimorphisms, respectively. They are interchanged when passing to the dual category.

Citations

- Herstein 1975, §2, p. 26

- Hall 1967, §1.1, p. 1: "The idea of a group is one which pervades the whole of mathematics both pure and applied."

- Lang 2005, App. 2, p. 360

- Cook, Mariana R. (2009), Mathematicians: An Outer View of the Inner World, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, p. 24, ISBN 9780691139517

- Artin 2018, §2.2, p. 40

- Lang 2002, I.§1, p. 3 and I.§2, p. 7

- Lang 2005, II.§1, p. 16

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Identity Element". MathWorld.

- Herstein 1975, §2.6, p. 54

- Wussing 2007

- Kleiner 1986

- Smith 1906

- Galois 1908

- Kleiner 1986, p. 202

- Cayley 1889

- Wussing 2007, §III.2

- Lie 1973

- Kleiner 1986, p. 204

- Wussing 2007, §I.3.4

- Jordan 1870

- von Dyck 1882

- Curtis 2003

- Mackey 1976

- Borel 2001

- Aschbacher 2004

- Ledermann 1953, §1.2, pp. 4–5

- Ledermann 1973, §I.1, p. 3

- Lang 2002, §I.2, p. 7

- Lang 2005, §II.1, p. 17

- Artin 2018, p. 40.

- Lang 2005, §II.3, p. 34

- Lang 2005, §II.1, p. 19

- Ledermann 1973, §II.12, p. 39

- Lang 2005, §II.4, p. 41

- Lang 2002, §I.2, p. 12

- Lang 2005, §II.4, p. 45

- Lang 2002, §I.2, p. 9

- Hatcher 2002, Chapter I, p. 30

- Coornaert, Delzant & Papadopoulos 1990

- for example, class groups and Picard groups; see Neukirch 1999, in particular §§I.12 and I.13

- Seress 1997

- Lang 2005, Chapter VII

- Rosen 2000, p. 54 (Theorem 2.1)

- Lang 2005, §VIII.1, p. 292

- Lang 2005, §II.1, p. 22

- Lang 2005, §II.2, p. 26

- Lang 2005, §II.1, p. 22 (example 11)

- Lang 2002, §I.5, p. 26, 29

- Weyl 1952

- Conway, Delgado Friedrichs & Huson et al. 2001. See also Bishop 1993

- Bersuker, Isaac (2006), The Jahn-Teller Effect, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 0-521-82212-2

- Jahn & Teller 1937

- Dove, Martin T (2003), Structure and Dynamics: an atomic view of materials, Oxford University Press, p. 265, ISBN 0-19-850678-3

- Welsh 1989

- Mumford, Fogarty & Kirwan 1994

- Lay 2003

- Kuipers 1999

- Fulton & Harris 1991

- Serre 1977

- Rudin 1990

- Robinson 1996, p. viii

- Artin 1998

- Lang 2002, Chapter VI (see in particular p. 273 for concrete examples)

- Lang 2002, p. 292 (Theorem VI.7.2)

- Kurzweil & Stellmacher 2004

- Artin 2018, Proposition 6.4.3. See also Lang 2002, p. 77 for similar results.

- Lang 2002, I.§3, p. 22

- Ronan 2007

- Mac Lane 1998

- Husain 1966

- Neukirch 1999

- Shatz 1972

- Milne 1980

- Warner 1983

- Borel 1991

- Goldstein 1980

- Weinberg 1972

- Naber 2003

- Becchi 1997

- Denecke & Wismath 2002

- Romanowska & Smith 2002

- Dudek 2001

References

General references

- Artin, Michael (2018), Algebra, Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-13-468960-9, Chapter 2 contains an undergraduate-level exposition of the notions covered in this article.

- Devlin, Keith (2000), The Language of Mathematics: Making the Invisible Visible, Owl Books, ISBN 978-0-8050-7254-9, Chapter 5 provides a layman-accessible explanation of groups.

- Hall, G. G. (1967), Applied group theory, American Elsevier Publishing Co., Inc., New York, MR 0219593, an elementary introduction.

- Herstein, Israel Nathan (1996), Abstract algebra (3rd ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Inc., ISBN 978-0-13-374562-7, MR 1375019.

- Herstein, Israel Nathan (1975), Topics in algebra (2nd ed.), Lexington, Mass.: Xerox College Publishing, MR 0356988.

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 211 (Revised third ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95385-4, MR 1878556

- Lang, Serge (2005), Undergraduate Algebra (3rd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-22025-3.

- Ledermann, Walter (1953), Introduction to the theory of finite groups, Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh and London, MR 0054593.

- Ledermann, Walter (1973), Introduction to group theory, New York: Barnes and Noble, OCLC 795613.

- Robinson, Derek John Scott (1996), A course in the theory of groups, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-94461-6.

Special references

- Artin, Emil (1998), Galois Theory, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-62342-9.

- Aschbacher, Michael (2004), "The Status of the Classification of the Finite Simple Groups" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 51 (7): 736–740.

- Becchi, C. (1997), Introduction to Gauge Theories, p. 5211, arXiv:hep-ph/9705211, Bibcode:1997hep.ph....5211B.

- Besche, Hans Ulrich; Eick, Bettina; O'Brien, E. A. (2001), "The groups of order at most 2000", Electronic Research Announcements of the American Mathematical Society, 7: 1–4, doi:10.1090/S1079-6762-01-00087-7, MR 1826989.

- Bishop, David H. L. (1993), Group theory and chemistry, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-67355-4.

- Borel, Armand (1991), Linear algebraic groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 126 (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97370-8, MR 1102012.

- Carter, Roger W. (1989), Simple groups of Lie type, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-50683-6.

- Conway, John Horton; Delgado Friedrichs, Olaf; Huson, Daniel H.; Thurston, William P. (2001), "On three-dimensional space groups", Beiträge zur Algebra und Geometrie, 42 (2): 475–507, arXiv:math.MG/9911185, MR 1865535.

- Coornaert, M.; Delzant, T.; Papadopoulos, A. (1990), Géométrie et théorie des groupes [Geometry and Group Theory], Lecture Notes in Mathematics (in French), 1441, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-52977-4, MR 1075994.

- Denecke, Klaus; Wismath, Shelly L. (2002), Universal algebra and applications in theoretical computer science, London: CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-58488-254-1.

- Dudek, W.A. (2001), "On some old problems in n-ary groups", Quasigroups and Related Systems, 8: 15–36.

- Frucht, R. (1939), "Herstellung von Graphen mit vorgegebener abstrakter Gruppe [Construction of Graphs with Prescribed Group]", Compositio Mathematica (in German), 6: 239–50, archived from the original on 2008-12-01.

- Fulton, William; Harris, Joe (1991), Representation theory. A first course, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Readings in Mathematics, 129, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97495-8, MR 1153249

- Goldstein, Herbert (1980), Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.), Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing, pp. 588–596, ISBN 0-201-02918-9.

- Hatcher, Allen (2002), Algebraic topology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-79540-1.

- Husain, Taqdir (1966), Introduction to Topological Groups, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, ISBN 978-0-89874-193-3

- Jahn, H.; Teller, E. (1937), "Stability of Polyatomic Molecules in Degenerate Electronic States. I. Orbital Degeneracy", Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 161 (905): 220–235, Bibcode:1937RSPSA.161..220J, doi:10.1098/rspa.1937.0142.

- Kuipers, Jack B. (1999), Quaternions and rotation sequences—A primer with applications to orbits, aerospace, and virtual reality, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-05872-6, MR 1670862.

- Kuga, Michio (1993), Galois' dream: group theory and differential equations, Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston, ISBN 978-0-8176-3688-3, MR 1199112.

- Kurzweil, Hans; Stellmacher, Bernd (2004), The theory of finite groups, Universitext, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-40510-0, MR 2014408.

- Lay, David (2003), Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-70970-4.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998), Categories for the Working Mathematician (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98403-2.

- Michler, Gerhard (2006), Theory of finite simple groups, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86625-5.

- Milne, James S. (1980), Étale cohomology, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08238-7

- Mumford, David; Fogarty, J.; Kirwan, F. (1994), Geometric invariant theory, 34 (3rd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-56963-3, MR 1304906.

- Naber, Gregory L. (2003), The geometry of Minkowski spacetime, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-43235-9, MR 2044239.

- Neukirch, Jürgen (1999), Algebraic Number Theory, Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, 322, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-65399-8, MR 1697859, Zbl 0956.11021

- Romanowska, A.B.; Smith, J.D.H. (2002), Modes, World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-02-4942-7.

- Ronan, Mark (2007), Symmetry and the Monster: The Story of One of the Greatest Quests of Mathematics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280723-6.

- Rosen, Kenneth H. (2000), Elementary number theory and its applications (4th ed.), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-87073-2, MR 1739433.

- Rudin, Walter (1990), Fourier Analysis on Groups, Wiley Classics, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0-471-52364-X.

- Seress, Ákos (1997), "An introduction to computational group theory" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 44 (6): 671–679, MR 1452069.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1977), Linear representations of finite groups, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90190-9, MR 0450380.

- Shatz, Stephen S. (1972), Profinite groups, arithmetic, and geometry, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08017-8, MR 0347778

- Suzuki, Michio (1951), "On the lattice of subgroups of finite groups", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 70 (2): 345–371, doi:10.2307/1990375, JSTOR 1990375.

- Warner, Frank (1983), Foundations of Differentiable Manifolds and Lie Groups, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90894-6.

- Weinberg, Steven (1972), Gravitation and Cosmology, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-92567-5.

- Welsh, Dominic (1989), Codes and cryptography, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853287-3.

- Weyl, Hermann (1952), Symmetry, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-02374-8.

Historical references

- Borel, Armand (2001), Essays in the History of Lie Groups and Algebraic Groups, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-0288-5

- Cayley, Arthur (1889), The collected mathematical papers of Arthur Cayley, II (1851–1860), Cambridge University Press.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "The development of group theory", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Curtis, Charles W. (2003), Pioneers of Representation Theory: Frobenius, Burnside, Schur, and Brauer, History of Mathematics, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2677-5.

- von Dyck, Walther (1882), "Gruppentheoretische Studien (Group-theoretical Studies)", Mathematische Annalen (in German), 20 (1): 1–44, doi:10.1007/BF01443322, S2CID 179178038, archived from the original on 2014-02-22.

- Galois, Évariste (1908), Tannery, Jules (ed.), Manuscrits de Évariste Galois [Évariste Galois' Manuscripts] (in French), Paris: Gauthier-Villars (Galois work was first published by Joseph Liouville in 1843).

- Jordan, Camille (1870), Traité des substitutions et des équations algébriques [Study of Substitutions and Algebraic Equations] (in French), Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

- Kleiner, Israel (1986), "The Evolution of Group Theory: A Brief Survey", Mathematics Magazine, 59 (4): 195–215, doi:10.2307/2690312, JSTOR 2690312, MR 0863090.

- Lie, Sophus (1973), Gesammelte Abhandlungen. Band 1 [Collected papers. Volume 1] (in German), New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., MR 0392459.

- Mackey, George Whitelaw (1976), The theory of unitary group representations, University of Chicago Press, MR 0396826

- Smith, David Eugene (1906), History of Modern Mathematics, Mathematical Monographs, No. 1.

- Wussing, Hans (2007), The Genesis of the Abstract Group Concept: A Contribution to the History of the Origin of Abstract Group Theory, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-45868-7.