McMillan Plan

The McMillan Plan (formally titled The Report of the Senate Park Commission. The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia) is a comprehensive planning document for the development of the monumental core and the park system of Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. It was written in 1902 by the Senate Park Commission. The commission is popularly known as the McMillan Commission after its chairman, Senator James McMillan of Michigan.[1]

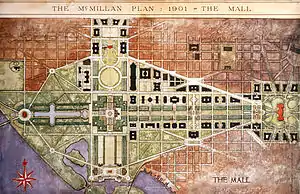

The McMillan Plan proposed eliminating the Victorian landscaping of the National Mall and replacing it with a simple expanse of grass, narrowing the Mall, and permitting the construction of low, Neoclassical museums and cultural centers along the Mall's east–west axis. The plan proposed constructing major memorials on the western and southern anchors of the Mall's two axes, reflecting pools on the southern and western ends, and massive granite and marble terraces and arcades around the base of the Washington Monument. The plan also proposed tearing down the existing railroad passenger station on the National Mall and constructing a large new station north of the United States Capitol building.

Additionally, the McMillan Plan contemplated the construction of clusters of tall, Neoclassical office buildings around Lafayette Square and the Capitol building, as well as an extensive system of neighborhood parks and recreational facilities throughout the city. Major new parkways would connect these parks as well as link the city to nearby attractions.

Never formally adopted by the United States government, the McMillan Plan was implemented piecemeal in the decades after its release. The location of the Lincoln Memorial, Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, Union Station, and U.S. Department of Agriculture Building are due to the McMillan Plan. Proposals to construct Arlington Memorial Bridge received a major boost from the plan as well. The McMillan Plan continues to guide urban planning in and around Washington, D.C., into the 21st century, and has become a part of the federal government's official planning policy for the national capital.

Senate Park Commission

Beginning around 1880, a series of articles appeared in the local D.C. and national press which were highly critical of the mediocre architecture and poor-quality public spaces and accommodations in the District of Columbia. In addition, a highly influential meeting of the American Institute of Architects was held in Washington in December 1900, during which not only were the city's shortcomings extensively discussed but plans proposed for rectifying them.[2] The plan presented at that meeting by Washington-based architect Paul J. Pelz anticipates several decisions in the eventual McMillan Plan, including the grouping of Congressional office buildings around the Capitol, the development of Federal Triangle, and the location of the National Archives Building.[3]

The Senate Park Commission was formed by the United States Senate on March 8, 1901, to reconcile competing visions for the development of Washington, D.C., and especially the National Mall and nearby areas.[4] McMillan Commission members included architect Daniel Burnham, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and architect Charles F. McKim.[5] Charles Moore, Senator McMillan's chief aide, became secretary of the commission. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens joined the commission as its last member in August 1901 at the suggestion of McKim.[6]

The commission members (excluding Saint-Gaudens, who was ill with cancer)[7] and Moore departed for Europe on June 13, 1901, to tour the continent's great manor homes, gardens, and urban landscapes. By the time the commission returned to the United States on August 1, Moore had become a de facto member of the commission.[8]

Description of the plan

The commission sponsored a major exhibit about their proposals at the Corcoran Gallery of Art on January 15, 1902, the same day the report was released to the public.[9] President Theodore Roosevelt attended the exhibit's opening. The exhibit was dominated by two vast models of the District of Columbia, one showing it as it existed in 1901 and the other showing the changes proposed by the Senate Park Commission. [10]

Seventy-one of the report's pages discussed proposals for the National Mall, while the remaining 100 pages discussed improvements for the park system in and around the city.[11] The proposals for the National Mall received the greatest attention from the commission, and were the most detailed.[12] The proposals for the city's parks, beaches, and recreational facilities (ostensibly the reason for its existence) were treated in more general ways.[13] Scattered throughout the plan were references to streets, boulevards, parkways, and various other connections between District and regional parks and the District and the surrounding cities and undeveloped areas.[14]

The National Mall and the "monumental core"

The report proposed turning the National Mall into the core of the growing city. A cruciform design for the Mall was proposed. The United States Capitol building anchored the east end of the east–west axis, and the White House the north end of the north–south axis. In the center was the Washington Monument. The recently completed West Potomac Park would be the anchor for the west end of the east–west axis. The commission suggested the recently authorized Lincoln Memorial be sited in the park, while proposing that the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial be moved to a new plaza to be constructed directly west of the Capitol. The recently created East Potomac Park would anchor the southern end of the north–south axis, and be occupied by a vast complex of recreational facilities ("Washington Commons") as well as a possible new memorial (to the Founding Fathers or great inventors, the report suggested). Andrew Jackson Downing's winding Victorian landscape design on the National Mall would be replaced with an open vista of grass flanked by formal rows of trees similar to the landscape design at Vaux-le-Vicomte and the Palace of Versailles in France. The width of the Mall, determined after extensive on-site measurements, would be narrowed to just 300 feet (91 m). The north and south sides of the National Mall were to be lined with low public office buildings, museums, and cultural attractions (such as theaters). The plan also suggested constructing a low, Beaux-Arts bridge linking West Potomac Park with Arlington National Cemetery. Around the base of the Washington Monument, new formal gardens and terraces would help to frame the base of the monument. The Pennsylvania Railroad's Baltimore & Potomac (B&P) Railroad Passenger Terminal, located on the National Mall at what is today New Jersey Avenue NW and Constitution Avenue NW, would be torn down and a new, modern train station with a grand court and massive passenger waiting and service areas would be constructed north of the Capitol. Two new reflecting pools (or "canals") would be constructed on the National Mall. One (cruciform in shape) would extend from West Potomac Park to the Washington Monument. The other would extend from East Potomac Park north to the Washington Monument. The Ellipse would remain open space in order to preserve the vista from the White House south to the Washington Monument and the Potomac River.[15]

The L'Enfant Plan's diagonal streets formed the great boundaries of the city's new "monumental core". Pennsylvania Avenue NW, already an important thoroughfare, formed the northeast boundary linking the Capitol with the White House. The report asked the federal government to tear down the vast slum Murder Bay and replace it with a group of monumental federal office buildings similar to Westminster in London or the Louvre Palace in Paris. Lafayette Square north of the White House would also be razed, and new federal office buildings in the Neoclassical style built there. New York Avenue NW would be extended in a southwesterly direction past the White House to link with the new memorial in West Potomac Park. Maryland Avenue SW, extending from the Capitol to East Potomac Park, would form the southeastern boundary of this new monumental core, while the Potomac River formed the southwestern boundary. The commission suggested that taller federal buildings and museums be constructed in areas not immediately adjacent to the National Mall.[16]

The city park system and parkways

The park system proposed by the McMillan Plan drew heavily on the Metropolitan Park System of Greater Boston (also designed by Olmsted). The commission proposed establishing large numbers of neighborhood parks throughout the city, especially in those areas outside the old "Federal City" boundaries.[lower-alpha 1] Public bathing and swimming facilities, gymnasiums, and playgrounds were an integral part of each proposed park, and the commission's report provided extensive drawings of "model parks". The commission's goal was to transform parks from places where the wealthy promenaded for purposes of social mobility into places where the average citizen could reap the advantages of physical exercise while enjoying the moral uplift provided by a natural setting within an urban area. Of critical importance to the commission was the development of the Anacostia Flats along the Anacostia River. The flats (like West and East Potomac Parks) had recently been reclaimed by dumping dredged material along the riverbank to eliminate marshes. The commission suggested building roads to provide access to the Anacostia River, and constructing a large water park for boating, bathing, swimming, and other uses to draw development to the area.[16]

Linking the more important parks would be a series of parkways, designed to allow citizens in carriages (the automobile not having come into widespread use) to become emotionally refreshed by viewing nature. Parkways were envisioned along the south side of the Potomac River from Arlington National Cemetery down to Mount Vernon, and from West Potomac Park through Rock Creek Park to the National Zoological Park. Another parkway (known as "Fort Drive"), nearly circumferential around the city, would link newly created parks designed to preserve the historic Civil War forts which circled the District of Columbia.[16]

Implementation of the plan

Implementation of the McMillan Plan was opposed by the powerful Speaker of the House, Joseph Gurney Cannon. Cannon was angry that the Senate had bypassed the House in creating the commission, and he was strongly opposed to spending the enormous sums that it would take to complete the plan. Although Moore had implemented a carefully planned public relations campaign to win congressional and public support for the McMillan Plan, it was clear that seeking formal approval of the plan from Congress was out of the question due to Cannon's opposition. Instead, members of the commission worked strenuously to ensure that the plan was not encroached upon, while waiting for a more opportune time to seek its implementation. Backers of the plan in Congress regularly called upon commission members to testify before Congress and in public hearings to defend the plan.

One of the most important goals of the McMillan Plan was to demolish the B&P Railroad Passenger Terminal. This proposal had generated widespread support in Congress for years, and on May 15, 1902, legislation was passed authorizing construction of a new Union Station. Although extensive disagreement broke out in the House over reimbursing the Pennsylvania Railroad for the cost of moving its tracks, legislation providing this reimbursement passed in 1903. The terminal was demolished in 1908.

The first major threat to implementing the McMillan Plan came in 1904. A new United States Department of Agriculture building had long been proposed for the south side of the National Mall between 7th and 14th Streets SW. The Department of Agriculture wanted to use all the space allotted to it, but McMillan Plan advocates argued that agriculture headquarters should be set back from the center of the National Mall by 300 feet (91 m). Department of Agriculture officials, however, pointed out that the 300-foot (91 m) setback from the mall's center-line was already violated on the south side of the mall by the Smithsonian Institution Building. President Theodore Roosevelt gave his approval for construction of a new agriculture building in line with the Smithsonian headquarters, only to later learn that his decision violated the McMillan Plan (which he also supported). Agriculture officials then argued that, if they had to accept a smaller plot of land, they should be permitted to construct a taller building to compensate for the loss of space. Extensive disagreement broke out between Agriculture officials, members of Congress intent on keeping costs low, McMillan Plan advocates, and others not only about where the building should be placed but also how tall it should be. The new Agriculture Building was eventually built according to the McMillan Plan's 300-foot (91 m) setback line, and slightly lowered into the ground to accommodate the building's taller height.[20]

The next major test of the McMillan Plan came with the siting of the Lincoln Memorial. A Lincoln Memorial Commission was authorized by Congress in 1910, and the commission immediately began wrestling with the many competing proposals for the memorial's location. Concurrently, members of the disbanded McMillan Commission were tiring of the constant demands on their time and the unpaid nature of their role. President Roosevelt agreed that a permanent commission on the arts should be created to help guide decisions regarding art and architecture in accordance with the McMillan Plan. Roosevelt established a commission by executive order shortly before he left office, but President William Howard Taft dissolved it and won congressional approval for a statutory United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) in 1910. Several members of the McMillan Commission were appointed to the CFA, as were many McMillan Plan supporters. When the Lincoln Memorial Commission found itself riven by disagreement over the new memorial's site, it sought out the advice of the CFA. Together, the Lincoln Memorial Commission and CFA worked together to approval West Potomac Park as the site for the new monument. The site for the Lincoln Memorial was approved in June 1911.[21]

Over the years, other decisions were made which helped reinforce the status of the McMillan plan as the "official" development plan for the District of Columbia. These included the siting of the Freer Gallery of Art in 1923, the creation of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission in 1926 (which was formally charged with implementing the McMillan Plan), enactment of legislation authorizing the enlargement of the Capitol grounds in 1929 (in accordance with the McMillan Plan), and passage of the Capper-Cramton city park act (which sought to implement the McMillan Plan's park program).[20] Arlington Memorial Bridge was authorized in 1925 after President Warren G. Harding got caught in a three-hour traffic jam during the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. A lengthy fight over the location of the bridge occurred, but the CFA won the battle and the bridge's construction (in the low, classical style advocated by the McMillan Plan) was authorized by Congress on February 24, 1925. The Public Buildings Act of 1926 authorized the razing of the Murder Bay slum and the construction of Federal Triangle in 1926, and the Mount Vernon Memorial Parkway was authorized in 1928. Although construction of a massive terrace around the base of the Washington Monument proven unfeasible (it would have destabilized the monument's foundations), the National World War II Memorial was constructed at the eastern end of the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool in 2004.

Recent implementation efforts

The McMillan Plan continues to provide the underpinning for planning in the national capital in the 21st century. In 1997, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) issued a report entitled Extending the Legacy: Planning America's Capital.[22] The planning document was an attempt to update the McMillan Plan for the 21st century. It redefined the monumental core, and established new guidelines for locating museums, memorials, and federal buildings throughout the city. A second major report, Monumental Core Framework Plan: Connecting New Destinations with the National Mall, was issued in April 2009.[23] Written jointly by the NCPC and CFA, the planning document extends the McMillan Plan's values and planning concepts through the city. It proposed the creation of new "federal centers" through the city (away from the monumental core) and proposed redevelopment of the Washington Channel and Anacostia River waterfronts. A second planning effort, CapitalSpace, was also launched in 2009.[24] A joint initiative of the NCPC, the National Park Service, and the government of the District of Columbia, CapitalSpace is designed to implement six of the major unfinished proposals of the McMillan Plan. These include linking the Fort Circle Parks with trails and parkways, improving recreational facilities, enhancing and maintaining neighborhood parks, establishing new and repairing existing playgrounds and school play yards, ensuring the protection and restoration of natural areas within and near the city, and transforming small and underutilized parks into vibrant new neighborhood centers.

In late 2012, work began on two billion-dollar projects to implement Extending the Legacy: Planning America's Capital were announced. The first project, named "The Wharf", is a $1.45 billion redevelopment of the waterfront roughly between 9th and 7th Streets SW along the Washington Channel. The project will build 10 mixed-use buildings each 130 feet (40 m) high. A privately owned cultural center and new public park will be included in The Wharf. A total of 3,200,000 square feet (300,000 m2) will be built, with about two-thirds of that built in the first phase. Maine Avenue SW will be remodeled, Water Street SW will be decommissioned and demolished, a pedestrian promenade built where Water Street was, and two new piers (for both private and commercial use) will be constructed.[25] The second project announced is a $906 million project to replace and realign the aging Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge and build new interchanges between the bridge and Suitland Parkway, the bridge and Potomac Avenue SW, Suitland Parkway and Interstate 295, and Suitland Parkway and Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue. The current four-lane bridge will be replaced with a six-lane bridge and brought into a more north–south alignment from its current northwest–southeast alignment. The cost of the bridge replacement is estimated at $573.8 million. A traffic circle with a large field (to be used for public gatherings, and suitable for several new memorials) will connect the north end of the bridge with Potomac Avenue SW. A second massive traffic oval on the south end of the bridge will help connect it to Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue, and help expand the city's "monumental core" into Anacostia. Reconstruction of the two interchanges is estimated to cost $209.2 million. The remainder of the budgeted funds will help remodel South Capitol Street into an urban boulevard from an industrial corridor, and renovate New Jersey Avenue SE.[26]

Unbuilt portions of the McMillan Plan

Several elements of the McMillan Plan remained unbuilt.

One major element was the large system of granite and marble terraces, steps, and arcades ("Washington Monument Gardens") proposed for the grounds around the base of the Washington Monument. It was later determined that construction of these features would require the removal of large quantities of earth. This would have destabilized the monument's foundations, however, and none of the proposed elements were built. The Trust for the National Mall and the National Park Service sponsored a design competition in 2011 to revitalize the Mall as part of a $700 million plan to transform it into a world-class park. The design partnership of Weiss/Manfredi + OLIN won a portion of the competition to redesign the Washington Monument grounds and the nearby Sylvan Theater. If implemented, the plan would lightly terrace the grounds of the Washington Monument, while creating deep terraces at the Sylvan Theater to create seating.

Another unbuilt major element was a collection of tall, Neoclassical office buildings around Lafayette Square. This proposal went unbuilt as the federal government struggled to complete the Federal Triangle complex. The cost of constructing the office complex during the mid to late 1930s, and the lack of materials and manpower during World War II and the Korean War, kept the complex from being built. Although a major effort was made in 1960 to begin razing the historic homes around Lafayette Square, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy opposed their destruction and successfully lobbied Congress and the General Services Administration to retain the structures. Mrs. Kennedy persuaded President John F. Kennedy to allow architect John Carl Warnecke to design a plan to allow the construction of two federal office buildings behind the smaller, historic structures. Warnecke's plan led to the construction of the New Executive Office Building in 1965 and the Howard T. Markey National Courts Building in 1967. They were the only two large office buildings constructed near Lafayette Square, and neither was Neoclassical in design.

A third major unbuilt recommendation of the McMillan Plan involved the extensive "Washington Commons" recreational area on East and West Potomac Parks along the southern side of the Tidal Basin. The McMillan Plan envisioned extensive public bathing and swimming facilities along the Potomac River's edge here, as well as a number of athletic fields, several gymnasiums, and a stadium. Additionally, a major new Neoclassical or Beaux-Arts memorial would be constructed along the White House-Washington Monument axis to serve as the southern anchor of the cruciform National Mall plan. The Washington Commons was to have been built after the Washington Monument terraces and arcades. After it was determined that the Washington Monument grounds project could not be built, attention turned to Washington Commons. But by then the Great Depression was under way, and funds to complete the Tidal Basin in the form envisioned by the McMillan Plan no longer were available. In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed construction of a memorial to Thomas Jefferson on the south side of the Tidal Basin. Although the memorial was opposed by the CFA, President Roosevelt ordered its construction and the Jefferson Memorial was completed in 1943.

The proposed "Fort Circle Drive" is another unbuilt part of the plan. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy began pushing Congress to build Fort Circle Drive.[27] But civic leaders and the National Park Service openly questioned whether the plan had outgrown its usefulness.[28] They argued that the city had grown past the ring of forts that protected it a century earlier, and city roads already connected the parks (albeit not in the linear route envisioned by the McMillan Plan).[29] The plan to link the city's Civil War fort-parks via a grand drive was quietly dropped in the years that followed.

A final unbuilt recommendation of the McMillan Plan was the concept of grouping a large number of executive branch office buildings around the United States Congress. The concept was two-fold: To complement the existing United States Botanic Garden (built in 1867), Library of Congress Building (built in 1897), Cannon House Office Building (built in 1908), and Russell Senate Office Building (built in 1909) to create a symmetrical look to the Capitol environs; and to reduce the time and trouble it took for executive branch workers to serve the needs of Congress. No executive branch office buildings were ever constructed. A number of buildings were constructed nearby, but they were not in the symmetrical siting or design advocated by the McMillan Plan. These structures included the Longworth House Office Building (finished in 1933), the United States Supreme Court Building (finished in 1935), and the John Adams Library of Congress Building (finished in 1939). The Longworth and Adams buildings were both on the House side, and no attempt was made to purchase the land bounded by Maryland Avenue NE, 1st Street NE, and Constitution Avenue NE. This property was quickly developed with private office buildings without reference to the McMillan Plan. Yet another building, the Rayburn House Office Building, was built on the House side in 1965. This left the United States Capitol Complex unbalanced. Only in 1972 was the relatively small Dirksen Senate Office Building completed on the Senate side. Thus far, all the buildings constructed were within the Beaux-Arts or "stripped Neoclassical" style. But in 1976, construction on the James Madison Library of Congress Building was completed in the southeast corner of the Capitol Complex. Not only was this building on the House side (again), but it was Modernist in style and did not fit well architecturally with the other structures. This was followed in 1982 with the Modernist Hart Senate Office Building, whose primary concession to the Beaux-Arts style was a marble exterior.

Although many neighborhood parks were created in the District of Columbia pursuant to the McMillan Plan, the scope of expansion contemplated by the plan was not achieved. Implementation of the neighborhood park, playground, and recreational facilities program was left to the D.C. government, which lacked the extensive resources of the federal government to implement the McMillan Plan. Few areas beyond the old "Federal City" boundary were purchased for park or recreational land. As the city rapidly expanded, this land dramatically increased in price and the city found itself unable to obtain as much land as it wished. The inability of the city government to implement the scope of the McMillan Plan's park proposals is considered the largest failure the plan faced.

References

- Notes

- Originally, government officials did not foresee that the city of Washington would expand to fill the boundaries of the entire District of Columbia. The "Federal City", or City of Washington, originally lay within an area bounded by Boundary Street (northwest and northeast), 15th Street (east), East Capitol Street, the Anacostia River, the Potomac River, and Rock Creek.[17][18][19]

- Citations

- Tompkins 1993, p. xvii.

- Kohler 2006, p. xi.

- Wrenn 1996, pp. 60-65.

- Peterson 2003, pp. 78-91.

- Thomas 2002, p. 16.

- Peterson 2006, pp. 15-16.

- Rybczynski 2008, p. 61.

- Peterson 2006, pp. 20-21.

- Peterson 2006, p. 27.

- Gutheim & Lee 2006, p. 132.

- Kohler 2006, p. xii.

- Gillette 1995, p. 100.

- Davis 2008, p. 176, fn. 2.

- Gutheim & Lee 2006, p. 133.

- Gutheim & Lee 2006, pp. 129-138.

- Gutheim & Lee 2006, p. 138.

- Hagner 1904, p. 257.

- Hawkins 1991, p. 16.

- Bednar 2006, p. 15.

- Gutheim & Lee 2006, pp. 138-139.

- Thomas 2002, pp. 37-43.

- "Extending the Legacy". National Capital Planning Commission. 1997. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- National Capital Planning Commission; United States Commission of Fine Arts (2009). "Monumental Core Framework Plan". National Capital Planning Commission. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- National Capitol Planning Commission; National Park Service; Government of the District of Columbia (2009). "CapitalSpace: A Park System for the Nation's Capital". National Capital Planning Commission. Retrieved January 27, 2013; Neibauer, Michael (March 14, 2013). "D.C. Plans Transformation of Franklin Park". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- Lewis, Roger K. (December 21, 2012). "Southwest Waterfront Gets Its Long-Overdue Makeover". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- Halsey, Ashley III (December 31, 2012). "Decaying D.C. Bridge Reflects State of Thousands of Such Structures Nationwide". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 27, 2013; "Rebuilding Bridges in the District". The Washington Post. December 31, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- Strayer, Martha (May 28, 1963). "JFK Settles Battle Over Ft. Drive". Washington Daily News.

- National Capital Planning Commission 1965, pp. 3–9.

- "Fort Sites Eyed for Future Use". The Washington Post. October 2, 1964. p. A10.

Further reading

- Report of the Senate Park Commission. The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia. United States Senate. Committee on the District of Columbia. 57th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1902.

Bibliography

- Bednar, Michael J. (2006). L'Enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801883180.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Timothy (2008). "Beyond the Mall: The Senate Park Commission's Plans for Washington's Park System". In Glazer, Nathan; Fields, Cynthia R. (eds.). The National Mall: Rethinking Washington's Monumental Core. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801888052.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillette, Howard (1995). Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780812205299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gutheim, Frederick A.; Lee, Antoinette J. (2006). Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., from L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801883286.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hagner, Alexander (1904). "Street Nomenclature of Washington City". Records of the Columbia Historical Society: 237–261.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkins, Don Alexander (Spring–Summer 1991). "The Landscape of the Federal City: A 1792 Walking Tour". Washington History: 10–33.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kohler, Sue (2006). "Introduction". In Kohler, Sue; Scott, Pamela (eds.). Designing the Nation's Capital: The 1901 Plan for Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. ISBN 9780160752230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Capital Planning Commission (1965). Fort Park System: A Re-evaluation Study of Fort Drive. Washington, D.C.: National Capital Planning Commission.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peterson, Jon A. (2003). The Birth of City Planning in the United States: 1840–1917. Baltimore, Md.: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801872105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peterson, Jon A. (2006). "The Senate Park Commission Plan for Washington, D.C.: A New Vision for the Capital and the Nation". In Kohler, Sue; Scott, Pamela (eds.). Designing the Nation's Capital: The 1901 Plan for Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. ISBN 9780160752230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rybczynski, Witold (2008). "'A Simple Space of Turf': Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.'s Idea for the Mall". In Glazer, Nathan; Fields, Cynthia R. (eds.). The National Mall: Rethinking Washington's Monumental Core. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801888052.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Christopher A. (2002). The Lincoln Memorial and American Life. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691011943.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tompkins, Sally Kress (1993). A Quest for Grandeur: Charles Moore and the Federal Triangle. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 9781560981619.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wrenn, Tony P. (2006). "The American Institute of Architects Convention of 1900: Its Influence on the Senate Park Commission Plan". In Kohler, Sue; Scott, Pamela (eds.). Designing the Nation's Capital: The 1901 Plan for Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. ISBN 9780160752230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)