Media independence

Media independence is the absence of external control and influence on an institution or individual working in the media. It is a measure of one's capacity to "make decisions and act according to its own logic,"[1] and distinguishes independent media from state media.

The concept of media independence has often been contested as a normative principle in media policy and journalism.[1] Nick Couldry (2009) considers that digital transformations tend to compromise the press as a common good (with a blurring of the difference between journalism and advertising, for example) by the technological, political and social dynamics that it brings. For this reason, authors such as Daniel Hallin,[2] Kelly McBride, and Tom Rosenstiel[3] consider other norms (such as transparency and participation) to be more relevant. Karppinen and Moe state that "what we talk about when we talk about media independence, then, are the characteristics of the relations between, on the one side, specific entities ranging from media institutions, via journalistic cultures, to individual speakers, and, on the other, their social environment, including the state, political interest groups, the market or the mainstream culture."[1]

Overview

Two factors tend to influence media independence. The disruption and crisis in business models that have supported print and broadcast media for decades have left traditional media outlets more vulnerable to external influences as they seek to establish new revenue sources. In many regions, austerity measures have led to large-scale budget cuts of public service broadcasters, dislocating employees and limiting innovation in programming.

An indicator of a lack of independence is the level of public trust in the credibility of journalism. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, trust in media seems to be declining, reflecting declines of trust in government, business and NGOs.[4] Since 2012, online media has become more and more popular, gaining trust throughout the world, but for Mindi Chahal, awareness on the risk of "fake-news", filter bubbles and algorithms has begun to change perceptions of the credibility of online information.[5] Anya Schiffrin says that despite the initial optimism that social media would reduce such tendencies by enabling broader citizen participation in media, there are growing signals that social media are similarly susceptible to political capture and polarization, further impacting on the trust that users may have towards information on these platforms.[6]

Media regulators impact on the editorial independence of the media, which is still deeply entwined with political and economic influences and pressures. Private media – functioning outside of governments' control and with minimum official regulation – are still dependent on advertising support, risking potential misuse of advertisers as a political tool by larger advertisers such as governments.[7]

New technologies has added new meaning to what constitutes media independence. The collection, selection, aggregation, synthesis and processing of data are now increasingly delegated to forms of automation. While the sharing of social media posts is crucial in elevating the importance of certain news sources or stories, what appears in individual news feeds on platforms such as Facebook or news aggregators such as Google News is the product of other forces as well. This includes algorithmic calculations, which remove professional editorial judgement, in favor of past consumption patterns by the individual user and his/her social network. In 2016, users declared preferring algorithms over editors for selecting the news they wanted to read.[8] Despite apparent neutrality algorithms may often compromise editorial integrity, and have been found to lead to discrimination against people based on their race, socio-economic situation and geographic location.[9][10]

Regulation

The role of regulatory authorities (license broadcaster institutions, content providers, platforms) and the resistance to political and commercial interference in the autonomy of the media sector are both considered as significant components of media independence. In order to ensure media independence, regulatory authorities should be placed outside of governments' directives. this can be measured through legislation, agency statutes and rules.[7]

Licensing

The process of issuing licenses in many regions still lacks transparency and is considered to follow procedures that are obscure and concealing. In many countries, regulatory authorities stand accused of political bias in favor of the government and ruling party, whereby some prospective broadcasters have been denied licenses or threatened with the withdrawal of licenses. In many countries, diversity of content and views have diminished as monopolies, fostered directly or indirectly by States.[7] This not only impacts on competition but leads to a concentration of power with potentially excessive influence on public opinion.[11] Buckley et al. cite failure to renew or retain licenses for editorially critical media; folding the regulator into government ministries or reducing its competences and mandates for action; and lack of due process in the adoption of regulatory decisions, among others, as examples in which these regulators are formally compliant with sets of legal requirements on independence, but their main task in reality is seen to be that of enforcing political agendas.[12]

Government endorsed appointments

State control is also evident in the increasing politicization of regulatory bodies operationalized through transfers and appointments of party-aligned individuals to senior positions in regulatory authorities.

Internet regulation

Governments worldwide have sought to extend regulation to internet companies, whether connectivity providers or application service providers, and whether domestically or foreign-based. The impact on journalistic content can be severe, as internet companies can err too much on the side of caution and take down news reports, including algorithmically, while offering inadequate opportunities for redress to the affected news producers.[7]

Regional

In Western Europe, self-regulation provides an alternative to state regulatory authorities. In such contexts, newspapers have historically been free of licensing and regulation, and there has been repeated pressure for them to self-regulate or at least to have in-house ombudsmen. However, it has often been difficult to establish meaningful self-regulatory entities.

In many cases, self-regulations exists in the shadow of state regulation, and is conscious of the possibility of state intervention. In many countries in Central and Eastern Europe, self-regulatory structures seems to be lacking or have not historically been perceived as efficient and effective.[13]

The rise of satellite delivered channels, delivered directly to viewers, or through cable or online systems, renders much larger the sphere of unregulated programing. There are, however, varying efforts to regulate the access of programmers to satellite transponders in parts of the Western Europe and North American region, the Arab region and in Asia and the Pacific. The Arab Satellite Broadcasting Charter was an example of efforts to bring formal standards and some regulatory authority to bear on what is transmitted, but it appears to not have been implemented.[14]

International organizations and NGO's

Self-regulation is expressed as a preferential system by journalists but also as a support for media freedom and development organizations by intergovernmental organizations such as UNESCO and non-governmental organizations. There has been a continued trend of establishing self-regulatory bodies, such as press councils, in conflict and post-conflict situations.

Major internet companies have responded to pressure by governments and the public by elaborating self-regulatory and complaints systems at the individual company level, using principles they have developed under the framework of the Global Network Initiative. The Global Network Initiative has grown to include several large telecom companies alongside internet companies such as Google, Facebook and others, as well as civil society organizations and academics.[15]

The European Commission’s 2013 publication, ICT Technology Sector Guide on Implementing the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, impacts on the presence of independent journalism by defining the limits of what should or should not be carried and prioritized in the most popular digital spaces.[16]

Private sector

Public pressure on technology giants has motivated the development of new strategies aimed not only at identifying ‘fake news’, but also at eliminating some of the structural causes of their emergence and proliferation. Facebook has created new buttons for users to report content they believe is false, following previous strategies aimed at countering hate speech and harassment online. These changes reflect broader transformations occurring among tech giants to increase their transparency. As indicated by the Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index, most large internet companies have reportedly become relatively more forthcoming in terms of their policies about transparency in regard to third party requests to remove or access content, especially in the case of requests from governments.[17] At the same time, however, the study signaled a number of companies that have become more opaque when it comes to disclosing how they enforce their own terms of service, in restricting certain types of content and account.[18]

Fact-checking and news literacy

In addition to responding to pressure for more clearly defined self-regulatory mechanisms, and galvanized by the debates over so-called ‘fake news’, internet companies such as Facebook have launched campaigns to educate users about how to more easily distinguish between ‘fake news’ and real news sources. Ahead of the United Kingdom national election in 2017, for example, Facebook published a series of advertisements in newspapers with ‘Tips for Spotting False News’ which suggested 10 things that might signal whether a story is genuine or not.[19] There have also been broader initiatives bringing together a variety of donors and actors to promote fact-checking and news literacy, such as the News Integrity Initiative at the City University of New York’s School of Journalism. This 14 million USD investment by groups including the Ford Foundation and Facebook was launched in 2017 so its full impact remains to be seen. It will, however, complement the offerings of other networks such as the International Fact-Checking Network launched by the Poynter Institute in 2015 which seeks to outline the parameters of the field.[20]

Influences in media systems

The media systems around the world are often put under pressure by the widespread delegitimisation by political actors of the media as a venerable institution along with the profession of journalism, and the growing efforts made towards media capture, particularly online media, which has often been regarded as more resistant to such form of control than other types of media.

Delegitimisation of models

Discreditation

Powerful actors such as governments have often been seen to initiate and engage in the process of systematic attacks on the media by trivializing it, or sometimes characterizing it as an ‘enemy’ has widespread implications for the independence and well-being of the sector. This can be particularly apparent during elections. A common tactic is to blur the distinction between mainstream news media, and the mass of unverified content on social media. Delegitimisation is a subtle and effective form of propaganda, reducing the public's confidence in the media to perform a collective function as a check on government. This can be seen as being linked political and social polarization.[7]

Attacks on media

In some regions, delegitimisation is reportedly combined with wider attacks on independent media: key properties have been closed down or sold to parties with ties to the government. Newer entrants linked to state power and vast resources gain sway. Opposition to these pressures may strengthen the defense of the press as civil society and mobilize the public in protest, but in some cases, this conflict leads to fear-induced apathy or withdrawal. Advertisers and investors may be scared-off by delegitimisation.[7]

Criminal defamation

Efforts to curtail criminal defamation are still ongoing in many regions but the dangers from civil lawsuits with high costs and high risk are also rising, leading to a greater likelihood of bankruptcy of media outlets. Independence is weakened where the right of journalists to criticize public officials is threatened. A general assault on the media can lead to measures making journalists more frequently liable for publishing state secrets and their capacity to shield sources can be reduced. Delegitimizing the media makes it easier to justify these legal changes that make the news business even more precarious.

Media capture

Media capture refers to the full range of forces that can restrict or skew coverage. It has been defined as "a situation where the media have not succeeded in becoming autonomous in manifesting a will of their own, nor able to perform their main function, notably of informing people. Instead, they have persisted in an intermediate state, with vested interests, and not just the government, using them for other purposes."[21] Mungiu-Pippidi considers that capture corrupts the main role of the media: to inform the public, with media outlets instead opting to trade influence and manipulate information.[22] A distinguishing feature of media capture is the collaboration by the private sector. Cases abound across all regions of bloggers and citizen journalists putting a spotlight on specific issues and reporting on the ground during protests.[23]

Full capture can also be complicated to achieve. Paid trolls leading to phenomena such as paid Twitter and mob attacks, along with fake news and rumors, are reportedly able to widely disseminate their attacks on independent journalists with the aid of bots. Across much of Africa, a trend of "serial callers" has become increasingly common. Also observed in other regions, such as in North America where the phenomenon is commonly referred to as "astroturfing", serial callers are often individuals commissioned by political actors to constantly phone in to popular radio call in programmes with the intention of skewing or influencing the program in their interest.[21] In some cases, the programme might be structurally biased towards such actors (e.g., there will be a dedicated phone for those that have planned to phone in with particular political sympathies) but in other cases the process is more ad hoc with sympathetic callers flooding particular radio programs.

Concentration of media ownership

Financial threats on media independence can be concentrated ownership power, bankruptcy, or unsustainable funding for public service broadcasters. Capital controls for media are in place in all regions to manage foreign direct investment in the media sector. Many governments in Africa, Latin America and Caribbean, and the Asia and Pacific regions have passed stringent laws and regulations that limit or forbid foreign media ownership, especially in the broadcasting and telecom sectors, with mixed impact on editorial independence. In Latin America, almost two thirds of the 15 countries covered by a World Bank study on foreign direct investments impose restrictions on foreign ownership in the newspaper-publishing sector. Almost all countries specify a cap on the foreign investment in media sector, although increasingly the strategy in the region has been to absorb private and foreign capital and experience of media management without losing ownership and political control of the media sector.[24] It is more complex to regulate ownership issues when the companies are internet platforms spanning multiple jurisdictions, although European competition and tax law has responded to some of the challenges in this regard, with unclear impact on the issue of independence of journalistic content on Internet companies.

New business models

Across the industry, media outlets have been re-evaluating where the value in media content lies, with a corresponding increase in government development programs, corporate benefactors and other special interests funding or cross-funding media content. These kinds of funding have been common historically in international broadcasting, and they typically influence actual media content, framing, and the ‘red lines’ different from professional principles that reporters feel unable to cross. While larger media companies have relied on attracting their own advertisers online, many online intermediaries such as Google Ads now exist, which effectively has meant that small online media companies can get some revenues without having to have dedicated facilities—although the requirements of platforms like Facebook for video content, and the power to change news feeds without consultation do compromise editorial autonomy. In addition, the media organization concerned can no longer exert strong control over what advertisements are shown, nor can it benefit from accessing full audience data to strengthen its own revenue prospects.[7]

Journalist perceptions

According to the Worlds of Journalism Study, journalists in 18 of the 21 countries surveyed in Western Europe and North America perceived their freedom to make editorial decisions independently to have shrunken in the past five years. In all other regions, a plurality of journalists in most countries reported their editorial freedom to have strengthened.[25] While there remains a marked decline in print advertising sales in these States, some newspapers are reporting an increase in digital advertising revenues and subscriptions that have enabled expansions of newsrooms that previously faced significant financial difficulty. This development partly reflects the relationship between major news brands and electoral cycles but it may also signal a growing willingness on the part of readers to pay for quality digital content.[26][27]

Mitigating political and economic interference

Several tools and organizations commit to mitigate political and economic interference in the media system.

Regulatory bodies

In some countries, the rise of trade bodies as a dominating site of advocacy seems to limit the plurality of voices involved or consulted to those representing mainly owner interests in decision-making. This has occurred as the lobbying power of media elites has increased with ownership consolidation, particularly in North America. In some cases, the relative formal independence of the media regulator from government may have made it more vulnerable to capture by commercial interests. Some of the board members from these trade bodies and associations sit on government working groups and are members of committees. Such members often facilitate the associations’ indirect participation in the drafting of media laws and policy.

Professionalization of regulatory bodies

According to the World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Global Report 2017/2018, there is a strong societal demand for the professionalization of regulatory and media bodies:

- Governmental alliances such as the Freedom Online Coalition and NGOs such as IFEX and the Media Legal Defence Initiative

- Training of lawyers and judges are gaining popularity. UNESCO has provided training in this vein to 5,000 employees of the judicial sector in Latin America, and is commencing a similar initiative in Africa.[28]

- There is also an increase in online training for journalism. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and increased internet access in all regions of the world: There are a number of distance learning programs based in the United States and United Kingdom, such as the Knight Centre for Journalism in the Americas, which also offers courses in Spanish serving countries in Latin America. The BBC Academy is another prominent example. The University of South Africa offers online degrees and short courses, including in media, to a global audience.

- Technology companies are demonstrating a growing interest in these activities, particularly as they attempt to influence policy at a domestic level. Google, Facebook, and others have recently established policy offices also in Africa and the Arab region with a mandate to support the development of conducive policies and legal frameworks, as well as informed lawyers and policymakers, for their products.[7]

Journalistic standards

- Codes of ethics are a common way to promote journalistic standards. While there have been a number of codes of ethics for journalists that aspire to universal status, and even some for ‘online journalists’ and bloggers, most transnational news agencies and broadcasters adhere to their own codes, although not all are publicly available.[14]

- In most regions, newspapers have developed their own codes of conduct with consistent values and standards that publishers and journalists should observe. Some newspapers have also appointed an ombudsman or readers’ representative to handle complaints from the public.

- In many countries, press councils and associations function like trade unions for journalists seeking to improve working conditions and to remove barriers journalists face when gathering news.

- Depending on the country, independent press councils are formed on a non-statutory basis and in some cases, they are mandated by law.[7]

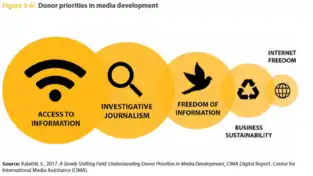

Donor priorities

Donor support of media development and freedom of expression non-governmental organizations can vary widely. A report by the National Endowment for Democracy’s Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) highlighted the swings in funding by tracking United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding to different regions over the past three years.[29]

Private foundations based in the Global North are increasingly providing grants to media organizations in the Global South. Such funds are often directed to cover specific topics of interest, such as health or education, and these donations can either support or weaken editorial independence.[30]

Gender equality

The media workplace

In the newsroom, women sometimes face hostility. This can be partly explained by the lack of organizational policies relating to gender equality and reporting mechanisms for harassment. The International Women’s Media Foundation’s 2011 global study of women in the news media, found that more than half of the news media organizations surveyed had a company-wide policy on gender equality, but with significant variations between regions. More than two-thirds of organizations based in Western Europe and Africa had such policies, compared with a quarter in the Middle East and North Africa and less than 20 per cent in Central and Eastern European countries.[31]

The European Institute for Gender Equality’s 2013 report, which looked at 99 major media houses across Europe, found that a quarter of organizations had policies that included a provision for gender equality, often as part of broader equality directives in the society. It was notable that of the 99 organizations, public service bodies were much more likely than commercial ones to have equality policies in place.[32]

Regional organizations

Several regional gender monitoring initiatives exist. The South Africa-based Gender Links, formed in 2001 to promote "gender equality in and through the media" in Southern Africa, leads the media cluster of the Southern Africa Gender Protocol Alliance.[33] Gender Links promotes media advocacy through global initiatives such as the Global Alliance on Media and Gender (GAMAG), hosting gender and media summits, developing policy in collaboration with regulators and working with media organizations through training and policy development.[34] Gender Links is currently developing Centres of Excellence for Gender in the Media in 108 newsrooms across Southern Africa and has established eight Centres of Excellence for Gender in Media Education.[35]

In 2016, the World Association for Christian Communication (WACC), the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) Network and other partners launched a campaign to end news media sexism by 2020. The ‘End News Media Sexism’ campaign encourages and supports advocacy initiatives that promote changes in media policies and journalism practice. The campaign is taking a multi-disciplinary approach and uses a variety of different tools to promote awareness, including a gender scorecard against which media organizations are measured.[36]

The African Women's Development and Communication Network (FEMNET), founded in 1988 as part of a broader project to promote women's empowerment in Africa, prioritizes women's development in the field of communication, where they have created and managed platforms to share information, ideas, strategies and experiences to foster cross-learning and more effective implementation of shared goals. FEMNET provides strategic policy recommendations through the production of reports and policy briefs. It has led extensive local capacity building initiatives, such as facilitating women's access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Africa.[37]

In Asia, the South Asia Women's Network (SWAN) has rolled out a research project titled "Women for Change: Building a Gendered Media in South Asia". Covering nine South Asian countries, it is partly supported by UNESCO's International Programme for the Development of Communication.[38]

National organizations

A number of national organizations work locally to redress the disparity in women's representation and participation in the media. Women, Media and Development (known by its Arabic acronym TAM) is a Palestine-based organization founded in 2004. TAM works with local women to promote their increased representation in the media and to foster an environment where they are able to effectively communicate and advocate for their rights. TAM provides training for women on how to access and use various media platforms, in addition to promoting community awareness and advocacy initiatives. TAM has facilitated capacity building and worked to counter stereotypes of women in the media by producing gender sensitive guides and training manuals, in addition to implementing projects that aim to increase women's access to decision-making positions and civic participation.[39]

Professional associations

Formal and informal networks of women media professionals support women in media. The Alliance for Women in Media (AWM), established in 1951 participate in training and professional development and celebrate their talents. In 1975, it began its annual programme of awards to recognize the work of programme-makers and content-providers in promoting women and women's issues.

Marie Colvin Journalists' Network – a bilingual Arabic-English online community of women journalists working in the Arab world – aims to assist vulnerable women journalist who lack support in relation to safety training, legal contracts, insurance or psychological care. The network links experienced journalists with new or isolated journalists for mentoring and peer-to-peer support, while also working closely with experts in media law, digital security, and health and safety to ensure specialized advice and assistance.[40]

Media unions at local, regional and global levels have established caucuses for women and have campaigned to encourage more women to stand for elected office within formal union structures. In 2001, the International Federation of Journalists found that women represented 29 per cent of union membership in 38 countries but just 17 per cent of members on union governing bodies: in its 2010 report, it found that women's representation on boards had increased only slightly, to 15 per cent. In Europe, between 2006 and 2013, women's union membership went down from 45 per cent to 42 per cent and board membership also declined, from 39 per cent to 36 per cent.[41]

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY SA 3.0 IGO License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Global Report 2017/2018, 202, UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY SA 3.0 IGO License statement/permission on Wikimedia Commons. Text taken from World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Global Report 2017/2018, 202, UNESCO.

References

- Karppinen, Kari; Moe, Hallvard (2016). ""What We Talk About When Talk About "Media Independence".", Javnost – The Public. Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture". Javnost – the Public. 23 (2): 105–119. doi:10.1080/13183222.2016.1162986. hdl:1956/12265.

- Hallin, Daniel C. 2006. “The Passing of the ‘High Modernism’ of American Journalism Revisited.” Political Communication Report 16 (1).

- McBride, Kelly, and Tom Rosenstiel. 2013. “Introduction: New Guiding Principles for a New Era of Journalism.” In The New Ethics of Journalism. Principles for the 21st Century, edited by KellyMcBride and Tom Rosenstiel, 1–6. London: Sage

- Edelman. 2017. Trust Barometer. Edelman. Available at https://www.edelman.com/trust2017/. Accessed 11 June 2017.

- Chahal, Mindi. 2017. The fake news effect and what it means for advertisers. Marketing Week. Available at https://www.marketingweek.com/2017/03/27/the-fake-news-effect/. Accessed 25 May 2017.

- Schriffen, Anya. 2017b. In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy. Washington, DC: Center for International Media Assistance. Available at https://www.cima.ned.org/resource/service-power-media-capture-threat-democracy/

- World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Global Report 2017/2018. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002610/261065e.pdf: UNESCO. 2018. p. 202.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Levy, David, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Nic Newman, and Richard Fletcher. 2016. Reuters Institute Digital News Report. Digital News Report. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available at http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/. Accessed 22 January 2017.

- Turow, Joseph. 2013. Branded Content, Media Firms, and Data Mining: An Agenda for Research. Presentation to ICA 2013 Conference, London, UK. Available at http://web.asc.upenn.edu/news/ICA2013/Joseph_Turow.pdf.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2014. Algorithmic Accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism 3 (3): 398–415.

- Hanretty, Chris. 2014. Media outlets and their moguls: Why concentrated individual or family ownership is bad for editorial independence. European Journal of Communication 29 (3): 335–350.

- Buckley, Steve, Kreszentia Duer, Toby Mendel, and Sean O. Siochru. 2008. Broadcasting, Voice, and Accountability : A Public Interest Approach to Policy, Law, and Regulation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Fengler, Susanne, Tobias Eberwein, Salvador Alsius, Olivier Baisnée, Klaus Bichler, Boguslawa Dobek-Ostrowska, Huub Evers, et al. 2015. How effective is media self-regulation? Results from a comparative survey of European journalists. European Journal of Communication 30 (3): 249–266.

- UNESCO. 2014. World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development. Paris: UNESCO Available at https://en.unesco.org/world-media-trends-2017/previous-editions

- Global Network Initiative (GNI). 2017. Global Network Initiative Adds Seven Companies in Milestone Expansion of Freedom of Expression and Privacy Initiative. Available at https://globalnetworkinitiative.org/global-network-initiative-adds-seven-companies-in-milestone-expansion-of-freedom-of-expression-and-privacy-initiative/.

- European Commission. Shift and Institute for Human Rights and Business, 2013. https://www.ihrb.org/pdf/eu-sector-guidance/EC-Guides/ICT/EC-Guide_ICT.pdf

- Ranking Digital Rights. 2015. Corporate Accountability Index. Available at https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2015/. Ranking Digital Rights. 2017. Corporate Accountability Index. Available at https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2017/.

- Ranking Digital Rights. 2017. Corporate Accountability Index. Available at https://rankingdigitalrights.org/index2017/.

- "Tips to Spot False News | Facebook Help Center | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- "International Fact-Checking Network fact-checkers' code of principles". Poynter. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- Gagliardone, Iginio; Matti, Pohjonen (2016). "Engaging in Polarized Society: Social Media and Political Discourse in Ethiopia". Engaging in Polarized Society: Social Media and Political Discourse in Ethiopia. In Digital Activism in the Social Media Era. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-40949-8_2: Springer International Publishing. pp. 25–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-40949-8_2. ISBN 978-3-319-40948-1.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. 2013. Freedom without Impartiality: The Vicious Circle of Media Capture. In Media Transformations in the Post-Communist World, edited by Peter Gross and Karol Jakubowicz. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- Allan, Stuart, and Einar Thorsen, eds. 2009. Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Global Crises and the Media. Peter Lang. Allan, Stuart. 2013. Citizen Witnessing: Revisioning Journalism in Times of Crisis. Key Concepts in Journalism Series. Polity. Hänska-Ahy, Maximillian T., and Roxanna Shapour. 2013. Who’s Reporting the Protests? Converging practices of citizen journalists and two BBC World Service newsrooms, from Iran’s election protests to the Arab uprisings. Journalism Studies 14 (1): 29–45. Mutsvairo, Bruce, ed. 2016. Participatory Politics and Citizen Journalism in a Networked Africa: A Connected Continent. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- The World Bank, International Finance Corporation (IFC), and Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) 2013.

- Worlds of Journalism Study 2016. The Worlds of Journalism Study is an academically driven project that was founded to regularly assess the state of journalism throughout the world. Its most recent wave brought together researchers from 67 countries, who interviewed 27,500 journalists between 2012 and 2016.

- Chatterjee, Lahiri. 2017. New York Times tops revenue estimates as digital subscriptions jump. Reuters. New York, United States edition, sec. Business. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-new-york-times-results-idUSKBN17Z1E0. Accessed 14 June 2017.

- Doctor, Ken. 2016. ‘Profitable’ Washington Post adding more than five dozen journalists. Politico Media. Available at https://www.politico.com/media/story/2016/12/the-profitable-washington-post-adding-more-than-five-dozen-journalists-004900. Accessed 8 June 2017

- "Training Judges Online to Safeguard Journalists". UNESCO. 2017-04-18. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- Kalathil, Shanthi. 2017. A Slowly Shifting Field: Understanding Donor Priorities in Media Development. CIMA Digital Report. Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA). Available at https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/slowly-shifting-field/.

- Schiffrin, Anya. 2017a. Same Beds, Different Dreams? Charitable Foundations and Newsroom Independence in the Global South. Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) & National Endowment for Democracy. Available at https://www.cima.ned.org/resource/beds-different-dreams-charitable-foundations-newsroom-independence-global-south/.

- Byerly, Carolyn M. 2011. Global Report on Status of Women in News Media. Washington D. C.: International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF). Available at https://www.iwmf.org/resources/global-report-on-the-status-of-women-in-the-news-media/. Accessed 8 June 2017.

- "European Institute for Gender Equality annual report 2013". publications.europa.eu. European Institute for Gender Equality. 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2018-07-04.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "About the Alliance – Gender Links". Gender Links. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- "GAMAG – Global Alliance on Media and Gender". gamag.net. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- "Centres of Excellence Archives".

- "WACC Launches "End News Media Sexism" campaign". waccglobal.org. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- "FEMNET – The African Women's Development and Communication Network". FEMNET – The African Women's Development and Communication Network. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- "South Asia Women's Network". www.swaninterface.net. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ".:: TAM ::". tam.ps. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- n.d. Marie Colvin Journalists’ Network. Marie Colvin Journalists’ Network. Available at https://mariecolvinnetwork.org/en/.

- "Publications & Reports: IFJ". www.ifj.org. Retrieved 2018-07-04.