Latin America

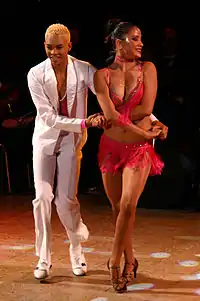

Latin America[lower-alpha 1] is a group of countries and dependencies in the Western Hemisphere where Romance languages such as Spanish, Portuguese, and French are predominantly spoken. Some subnational regions such as Quebec and parts of the United States where Romance languages are primarily spoken are not included due to the countries as a whole being a part of Anglo America (an exception to this is Puerto Rico, which is almost always included within the definition of Latin America despite being a territory of the United States). The term is broader than categories such as Hispanic America, which specifically refers to Spanish-speaking countries and Ibero-America, which specifically refers to both Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries. The term is also more recent in origin.

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Area | 20,111,457 km2 (7,765,077 sq mi)[1] |

|---|---|

| Population | 642,216,682 (2018 est.)[2][3][lower-alpha 2] |

| Population density | 31/km2 (80/sq mi) |

| Religions |

|

| Demonym | Latin American |

| Countries | 20[lower-alpha 3] |

| Dependencies | 14 |

| Languages | Romance languages Others: Quechua, Mayan languages, Guaraní, Aymara, Nahuatl, Haitian Creole, German, English, Dutch, Polish, Russian, Welsh, Yiddish, Greek, Chinese, Japanese, Others |

| Time zones | UTC−2 to UTC−8 |

| Largest cities | (Metro areas)[5][6] 1. São Paulo 2. Mexico City 3. Buenos Aires 4. Rio de Janeiro 5. Bogotá 6. Lima 7. Santiago 8. Belo Horizonte 9. Guadalajara 10. Monterrey |

| UN M49 code | 419 – Latin America019 – Americas001 – World |

The term "Latin America" was first used in an 1856 conference with the title "Initiative of America. Idea for a Federal Congress of the Republics" (Iniciativa de la América. Idea de un Congreso Federal de las Repúblicas),[7] by the Chilean politician Francisco Bilbao. The term was further popularised by French Emperor Napoleon III's government in the 1860s as Amérique latine to justify France's military involvement in Mexico and try to include French-speaking territories in the Americas such as French Canada, French Louisiana, or French Guiana, in the larger group of countries where Spanish and Portuguese languages prevailed.[8]

Including French-speaking territories, Latin America would consist of 20 countries and 14 dependent territories that cover an area that stretches from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego and includes much of the Caribbean. It has an area of approximately 19,197,000 km2 (7,412,000 sq mi),[1] almost 13% of the Earth's land surface area. As of March 2, 2020, population of Latin America and the Caribbean was estimated at more than 652 million,[9] and in 2019, Latin America had a combined nominal GDP of US$5,188,250 million[10] and a GDP PPP of 10,284,588 million USD.[10][11]

Etymology and definitions

Origins

There is no universal agreement on the origin of the term Latin America. Some historians believe that the term was created by geographers in the 16th century to refer to the parts of the New World colonized by Spain and Portugal, whose Romance languages derive from Latin. Others argue that the term arose in 1860s France during the reign of Napoleon III, as part of the attempt to create a French empire in the Americas.[12] The idea that a part of the Americas has a linguistic affinity with the Romance cultures as a whole can be traced back to the 1830s, in the writing of the French Saint-Simonian Michel Chevalier, who postulated that this part of the Americas was inhabited by people of a "Latin race", and that it could, therefore, ally itself with "Latin Europe", ultimately overlapping the Latin Church, in a struggle with "Teutonic Europe", "Anglo-Saxon America" and "Slavic Europe".[13]

Historian John Leddy Phelan located the origins of the term Latin America in the French occupation of Mexico. His argument is that French imperialists used the concept of "Latin" America as a way to counter British imperialism, as well as to challenge the German threat to France.[14] The idea of a "Latin race" was then taken up by Latin American intellectuals and political leaders of the mid- and late-nineteenth century, who no longer looked to Spain or Portugal as cultural models, but rather to France.[15] French ruler Napoleon III had a strong interest in extending French commercial and political power in the region he and his business promoter Felix Belly called "Latin America" to emphasize the shared Latin background of France with the former Viceroyalties of Spain and colonies of Portugal. This led to Napoleon's failed attempt to take military control of Mexico in the 1860s.[8]

However, though Phelan thesis is still frequently mentioned in the U.S. academy, two Latin American historians, the Uruguayan Arturo Ardao and the Chilean Miguel Rojas Mix proved decades ago that the term "Latin America" was used earlier than Phelan claimed, and the first use of the term was completely opposite to support imperialist projects in the Americas. Ardao wrote about this subject in his book Génesis de la idea y el nombre de América latina (Genesis of the Idea and the Name of Latin America, 1980),[16] and Miguel Rojas Mix in his article "Bilbao y el hallazgo de América latina: Unión continental, socialista y libertaria" (Bilbao and the Finding of Latin America: a Continental, Socialist and Libertarian Union, 1986).[17] As Michel Gobat reminds in his article "The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race", "Arturo Ardao, Miguel Rojas Mix, and Aims McGuinness have revealed [that] the term 'Latin America' had already been used in 1856 by Central Americans and South Americans protesting U.S. expansion into the Southern Hemisphere".[18] Edward Shawcross summarizes Ardao's and Rojas Mix's findings in the following way: "Ardao identified the term in a poem by a Colombian diplomat and intellectual resident in France, José María Torres Caicedo, published on 15 February 1857 in a French based Spanish-language newspaper, while Rojas Mix located it in a speech delivered in France by the radical liberal Chilean politician Francisco Bilbao in June 1856".[19]

Now under the administration of the United States, by the late 1850s, the term was being used in local California newspapers such as El Clamor Público by Californios writing about América latina and latinoamérica, and identifying as latinos as the abbreviated term for their "hemispheric membership in la raza latina".[20]

So, regarding when the words "Latin" and "America" were combined for the first time in a printed work, the term "Latin America" was first used in 1856 in a conference by the Chilean politician Francisco Bilbao in Paris.[21] The conference had the title "Initiative of the America. Idea for a Federal Congress of Republics."[7] The following year the Colombian writer José María Torres Caicedo also used the term in his poem "The Two Americas".[22] Two events related with the U.S. played a central role in both works. The first event happened less than a decade before the publication of Bilbao's and Torres Caicedo works: the Invasion of Mexico or, in USA the Mexican–American War, after which Mexico lost a third of its territory. The second event, the Walker affair, happened the same year both works were written: the decision by U.S. president Franklin Pierce to recognize the regime recently established in Nicaragua by American William Walker and his band of filibusters who ruled Nicaragua for nearly a year (1856–57) and attempted to reinstate slavery there, where it had been already abolished for three decades

In both Bilbao's and Torres Caicedo's works, the Mexican–American War and Walker's expedition to Nicaragua are explicitly mentioned as examples of dangers for the region. For Bilbao, "Latin America" was not a geographical concept, since he excluded Brazil, Paraguay and Mexico. Both authors also ask for the union of all Latin American countries as the only way to defend their territories against further foreign U.S. interventions. Both rejected also European imperialism, claiming that the return of European countries to non-democratic forms of government was another danger for Latin American countries, and used the same word to describe the state of European politics at the time: "despotism." Several years later, during the French invasion of Mexico, Bilbao wrote another work, "Emancipation of the Spirit in America," where he asked all Latin American countries to support the Mexican cause against France, and rejected French imperialism in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. He asked Latin American intellectuals to search for their "intellectual emancipation" by abandoning all French ideas, claiming that France was: "Hypocrite, because she [France] calls herself protector of the Latin race just to subject it to her exploitation regime; treacherous, because she speaks of freedom and nationality, when, unable to conquer freedom for herself, she enslaves others instead!"[23] Therefore, as Michel Gobat puts it, the term Latin America itself had an "anti-imperial genesis," and their creators were far from supporting any form of imperialism in the region, or in any other place of the globe.

However, in France the term Latin America was used with the opposite intention. It was employed by the French Empire of Napoleon III during the French invasion of Mexico as a way to include France among countries with influence in the Americas and to exclude Anglophone countries. It played a role in his campaign to imply cultural kinship of the region with France, transform France into a cultural and political leader of the area, and install Maximilian of Habsburg as emperor of the Second Mexican Empire.[24] This term was also used in 1861 by French scholars in La revue des races Latines, a magazine dedicated to the Pan-Latinism movement.[25]

Contemporary definitions

- Latin America is often used synonymously with Ibero-America ("Iberian America"), excluding the predominantly Dutch-, French- and English-speaking territories. Thus the countries of Haiti, Belize, Guyana and Suriname, and several French overseas departments, are excluded.[26]

- In a more literal definition, which is close to the semantic origin, Latin America designates countries in the Americas where a Romance language (a language derived from Latin) predominates: Spanish, Portuguese, French, and the creole languages based upon these. Thus it includes Mexico, most of Central and South America, and in the Caribbean, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico. Latin America is, therefore, defined as all those parts of the Americas that were once part of the Spanish, Portuguese and French Empires.[27][28]

- The term is sometimes used more broadly to refer to all of the Americas south of the United States,[28] thus including the Guianas (French Guiana, Guyana, and Suriname), the Anglophone Caribbean (and Belize); the Francophone Caribbean; and the Dutch Caribbean. This definition emphasizes a similar socioeconomic history of the region, which was characterized by formal or informal colonialism, rather than cultural aspects (see, for example, dependency theory).[29] Some sources avoid this simplification by using the alternative phrase "Latin America and the Caribbean", as in the United Nations geoscheme for the Americas.[30][31][32]

The distinction between Latin America and Anglo-America is a convention based on the predominant languages in the Americas by which Romance-language and English-speaking cultures are distinguished. Neither area is culturally or linguistically homogeneous; in substantial portions of Latin America (e.g., highland Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, Guatemala), Native American cultures and, to a lesser extent, Amerindian languages, are predominant, and in other areas, the influence of African cultures is strong (e.g., the Caribbean basin – including parts of Colombia and Venezuela).

The term is not without controversy. Historian Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo explores at length the "allure and power" of the idea of Latin America. He remarks at the outset, "The idea of 'Latin America' ought to have vanished with the obsolescence of racial theory... But it is not easy to declare something dead when it can hardly be said to have existed," going on to say, "The term is here to stay, and it is important."[33] Following in the tradition of Chilean writer Francisco Bilbao, who excluded Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay from his early conceptualization of Latin America,[34] Chilean historian Jaime Eyzaguirre has criticized the term Latin America for "disguising" and "diluting" the Spanish character of a region (i.e. Hispanic America) with the inclusion of nations that according to him do not share the same pattern of conquest and colonization.[35]

Subregions and countries

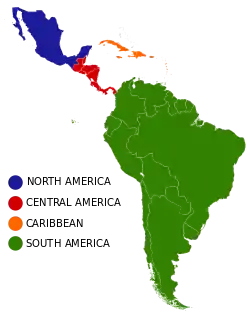

Latin America can be subdivided into several subregions based on geography, politics, demographics and culture. If defined as all of the Americas south of the United States, the basic geographical subregions are North America, Central America, the Caribbean and South America;[36] the latter contains further politico-geographical subdivisions such as the Southern Cone, the Guianas and the Andean states. It may be subdivided on linguistic grounds into Hispanic America, Portuguese America and French America.

| Flag | Arms | Country | Capital(s) | Name(s) in official language(s) | Area (km²) |

Population[2][3] (2018) |

Population density (per km²) |

Time(s) zone(s) | Subregion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Buenos Aires | Argentina | 2,780,400 | 44,361,150 | 14.4 | UTC/GMT -3 hours | South America | ||

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | Sucre and La Paz | Bolivia; Buliwya; Wuliwya; Volívia | 1,098,581 | 11,353,142 | 9 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | South America | ||

| Brazil | Brasília | Brasil | 8,515,767 | 209,469,323 | 23.6 | UTC/GMT -2 hours (Fernando de Noronha) UTC/GMT -3 hours (Brasília) UTC/GMT -4 hours (Amazonas) UTC/GMT -5 hours (Acre) |

South America | ||

| Chile | Santiago | Chile | 756,096 | 18,729,160 | 23 | UTC/GMT -3 hours (Magallanes and Chilean Antarctica) UTC/GMT -4 hours (Continental Chile) UTC/GMT -5 hours (Easter Island) |

South America | ||

| Colombia | Bogotá | Colombia | 1,141,748 | 49,661,048 | 41.5 | UTC/GMT -5 hours | South America | ||

| Costa Rica | San José | Costa Rica | 51,100 | 4,999,441 | 91.3 | UTC/GMT -6 hours | Central America | ||

| Cuba | Havana | Cuba | 109,884 | 11,338,134 | 100.6 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Dominican Republic | Santo Domingo | República Dominicana | 48,442 | 10,627,141 | 210.9 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Ecuador | Quito | Ecuador | 283,560 | 17,084,358 | 54.4 | UTC/GMT -5 hours | South America | ||

| El Salvador | San Salvador | El Salvador | 21,040 | 6,420,746 | 290.3 | UTC/GMT -6 hours | Central America | ||

| French Guiana* | Cayenne | Guyane | 83,534 | 282,938 | 3 | UTC/GMT -3 hours | South America | ||

| Guadeloupe* | Basse-Terre | Guadeloupe | 1,628 | 399,848 | 250 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Guatemala | Guatemala City | Guatemala | 108,889 | 17,247,849 | 129 | UTC/GMT -6 hours | Central America | ||

| Haiti | Port-au-Prince | Haïti; Ayiti | 27,750 | 11,123,178 | 350 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Honduras | Tegucigalpa | Honduras | 112,492 | 9,587,522 | 76 | UTC/GMT -6 hours | Central America | ||

| Martinique* | Fort-de-France | Martinique | 1,128 | 375,673 | 340 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Mexico | Mexico City | México | 1,964,375 | 126,190,788 | 57 | UTC/GMT -5 hours (Zona Sureste) UTC/GMT -6 hours (Zona Centro) UTC/GMT -7 hours (Zona Pacífico) UTC/GMT -8 hours (Zona Noroeste) |

North America | ||

| Nicaragua | Managua | Nicaragua | 130,375 | 6,465,501 | 44.3 | UTC/GMT -6 hours | Central America | ||

| Panama | Panama City | Panamá | 75,517 | 4,176,869 | 54.2 | UTC/GMT -5 hours | Central America | ||

| Paraguay | Asunción | Paraguay; Tetã Paraguái | 406,752 | 6,956,066 | 14.2 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | South America | ||

| Peru | Lima | Perú; Piruw | 1,285,216 | 31,989,260 | 23 | UTC/GMT -5 hours | South America | ||

| Puerto Rico* | San Juan | Puerto Rico | 9,104 | 3,039,596 | 397 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Saint Barthélemy* | Gustavia | Saint-Barthélemy | 25 | 9,961[37] | 398 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Saint Martin* | Marigot | Saint-Martin | 53.2 | 39,000 | 733 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | Caribbean | ||

| Uruguay | Montevideo | Uruguay | 176,215 | 3,449,285 | 18.87 | UTC/GMT -3 hours | South America | ||

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | Caracas | Venezuela | 916,445 | 28,887,118 | 31.59 | UTC/GMT -4 hours | South America | ||

| Total | 20,111,699 | 626,747,000 |

*: Not a sovereign state

History

Pre-Columbian history

The earliest known settlement was identified at Monte Verde, near Puerto Montt in Southern Chile. Its occupation dates to some 14,000 years ago and there is some disputed evidence of even earlier occupation. Over the course of millennia, people spread to all parts of the continents. By the first millennium CE, South America's vast rainforests, mountains, plains and coasts were the home of tens of millions of people. The earliest settlements in the Americas are of the Las Vegas Culture[38] from about 8000 BCE and 4600 BCE, a sedentary group from the coast of Ecuador, the forefathers of the more known Valdivia culture, of the same era. Some groups formed more permanent settlements such as the Chibcha (or "Muisca" or "Muysca") and the Tairona groups. These groups are in the circum Caribbean region. The Chibchas of Colombia, the Quechuas and Aymaras of Bolivia were the three indigenous groups that settled most permanently.

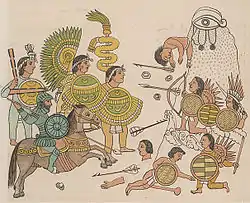

The region was home to many indigenous peoples and advanced civilizations, including the Aztecs, Toltecs, Maya, and Inca. The golden age of the Maya began about 250, with the last two great civilizations, the Aztecs and Incas, emerging into prominence later on in the early fourteenth century and mid-fifteenth centuries, respectively. The Aztec empire was ultimately the most powerful civilization known throughout the Americas, until its downfall in part by the Spanish invasion.

Iberian colonization

With the arrival of the Spaniards and Portuguese, the indigenous elites, such as the Incas and Aztecs, were deposed and/or co-opted. Hernándo Cortés seized the Aztec elite's power in alliance with peoples who had been subjugated by this polity. Francisco Pizarro eliminated the Incan rule in Peru. Both Spain and Portugal colonized and settled the Americas, which along with the rest of the uncolonized world, was divided among them by the line of demarcation in 1494. This treaty gave Spain all areas to the west, and Portugal all areas to the east (the Portuguese lands in South America subsequently becoming Brazil). By the end of the sixteenth century Spain and Portugal controlled territory extending from Alaska to the southern tips of the Patagonia. Iberian culture, customs and government were introduced with the settlers who widely intermarried with local populations. The Catholic Religion was the only official religion in all territories under Spanish and Portuguese rule.

Epidemics of diseases which came with the Spaniards, such as smallpox and measles, wiped out a large portion of the indigenous population. Historians cannot determine the number of natives who died due to European diseases, but some put the figures as high as 85% and as low as 25%. Due to the lack of written records, specific numbers are hard to verify. Many of the survivors were forced to work in European plantations and mines until indigenous slavery was outlawed with the New Laws of 1542. Unlike in English colonies, Intermixing between the indigenous peoples and Iberian colonists was very common and, by the end of the colonial period, people of mixed ancestry (mestizos) formed majorities in several colonies.

Slavery and forced labor in colonial Latin America

Indigenous peoples of the Americas in various colonies were forced to work in plantations and mines; along with African slaves who were also introduced in the proceeding centuries.

The Mita of Colonial Latin America was a system of forced labor imposed on the natives. First established by Viceroy Francisco de Toledo (1569–1581), the Mita was upheld by laws that designated how large draft levies were and how much money the workers would receive that was based on how many shifts each individual worker performed. Toledo established Mitas at Potosi and Huancavelica, where the Mitayos—the workers—would be reduced in number to a fraction of how many were originally assigned before the 1700s. While several villages managed to resist the Mita, others offered payment to colonial administrators as a way out. In exchange, free labor became available through volunteers, though the Mita was kept in place as workers like miners, for example, were paid low wages. The Spanish Crown had not made any ruling on the Mita or approved of it when Toledo first established it in spite of the uncertainty of the practice since the Crown could have gained benefits from it. However, the cortes of Spain later abolished it in 1812 once complaints of the Mita violating humanitarian rights were made. Yet complaints also came from: governors; landowners; native leaders known as Kurakas; and even priests, each of whom preferred other methods of economic exploitation. Despite its fall, the Mita made it to the 1800s.[39]

Another important group of slaves to mention were the slaves brought over from Africa. The first slaves came over with Christopher Columbus from the very beginning on his earliest voyages. However in the few hundred years, the Atlantic Slave trade would begin delivering slaves, imported by Spain and other colonizers, by the millions. Many of the large scale productions were run by forced slave labor. They were a part of sugar and coffee production, farming (beans, rice, corn, fruit, etc.), Mining, whale oil and multiple other jobs. Slaves were also house workers, servants, military soldiers, and much more. To say the least these people were property and treated as such. Though indigenous slaves existed, they were no match in quantity and lack of quality jobs when compared to the African slave. The slave population was massive compared to the better known slave ownership in the United States. After 1860 Brazil alone had imported over 4 million slaves, which only represented about 35% of the Atlantic slave trade. Despite the large number of slaves in Latin America, there was not as much reproduction of slaves amongst the population. Because most of the slaves then were African-born, they were more subject to rebellion. The United States involvement in the slave trade is well known amongst North America, however it hides a larger and in some ways crueler operation in the south which had a much longer history.[40]

Independence (1804–1825)

In 1804, Haiti became the first Latin American nation to gain independence, following a violent slave revolt led by Toussaint L'ouverture on the French colony of Saint-Domingue. The victors abolished slavery. Haitian independence inspired independence movements in Spanish America.

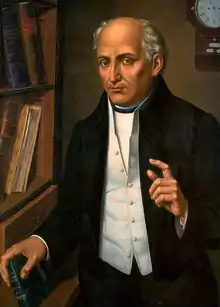

By the end of the eighteenth century, Spanish and Portuguese power waned on the global scene as other European powers took their place, notably Britain and France. Resentment grew among the majority of the population in Latin America over the restrictions imposed by the Spanish government, as well as the dominance of native Spaniards (Iberian-born Peninsulares) in the major social and political institutions. Napoleon's invasion of Spain in 1808 marked a turning point, compelling Criollo elites to form juntas that advocated independence. Also, the newly independent Haiti, the second oldest nation in the New World after the United States, further fueled the independence movement by inspiring the leaders of the movement, such as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla of Mexico, Simón Bolívar of Venezuela and José de San Martín of Argentina, and by providing them with considerable munitions and troops.

Fighting soon broke out between juntas and the Spanish colonial authorities, with initial victories for the advocates of independence. Eventually, these early movements were crushed by the royalist troops by 1810, including those of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla in Mexico in the year 1810. Later on Francisco de Miranda in Venezuela by 1812. Under the leadership of a new generation of leaders, such as Simón Bolívar "The Liberator", José de San Martín of Argentina, and other Libertadores in South America, the independence movement regained strength, and by 1825, all Spanish America, except for Puerto Rico and Cuba, had gained independence from Spain. In the same year in Mexico, a military officer, Agustín de Iturbide, led a coalition of conservatives and liberals who created a constitutional monarchy, with Iturbide as emperor. This First Mexican Empire was short-lived, and was followed by the creation of a republic in 1823.

Independent Empire of Brazil

The Brazilian War of Independence, which had already begun along other independent movements around the region, spread through northern, northeastern regions and in Cisplatina province.[41] With the last Portuguese soldiers surrendering on March 8, 1824,[42] Portugal officially recognized Brazil on August 29, 1825.[43]

On April 7, 1831, worn down by years of administrative turmoil and political dissensions with both liberal and conservative sides of politics, including an attempt of republican secession,[44] as well as unreconciled with the way that absolutists in Portugal had given to the succession of King John VI, Pedro I went to Portugal to reclaim his daughter's crown, abdicating the Brazilian throne in favor of his five-year-old son and heir (who thus became the Empire's second monarch, with the regnal title of Dom Pedro II).[45]

As the new Emperor could not exert his constitutional powers until he became of age, a regency was set up by the National Assembly.[46] In the absence of a charismatic figure who could represent a moderate face of power, during this period a series of localized rebellions took place, as the Cabanagem, the Malê Revolt, the Balaiada, the Sabinada, and the Ragamuffin War, which emerged from the dissatisfaction of the provinces with the central power, coupled with old and latent social tensions peculiar of a vast, slaveholding and newly independent nation state.[47] This period of internal political and social upheaval, which included the Praieira revolt, was overcome only at the end of the 1840s, years after the end of the regency, which occurred with the premature coronation of Pedro II in 1841.[48]

During the last phase of the monarchy, an internal political debate was centered on the issue of slavery. The Atlantic slave trade was abandoned in 1850,[49] as a result of the British' Aberdeen Act, but only in May 1888 after a long process of internal mobilization and debate for an ethical and legal dismantling of slavery in the country, was the institution formally abolished.[50]

On November 15, 1889, worn out by years of economic stagnation, in attrition with the majority of Army officers, as well as with rural and financial elites (for different reasons), the monarchy was overthrown by a military coup.[51]

Conservative–liberal conflicts in the 19th century

After the independence of many Latin American countries, there was a conflict between the people and the government, much of which can be reduced to the contrasting ideologies between liberalism and conservatism.[52] Conservatism was the dominant system of government prior to the revolutions and it was founded on having social classes, including governing by kings. Liberalists wanted to see a change in the ruling systems, and to move away from monarchs and social classes to promote equality.

When liberal Guadalupe Victoria became the first president of Mexico in 1824, conservatists relied on their belief that the state had been better off before the new government came into power, so, by comparison, the old government was better in the eyes of the Conservatives. Following this sentiment, the conservatives pushed to take control of the government, and they succeeded. General Santa Anna was elected president in 1833. The following decade, the Mexican–American War (1846–48) caused Mexico to lose a significant amount of territory to the United States. This loss led to a rebellion by the enraged liberal forces against the conservative government.

In 1837, conservative Rafael Carrera conquered Guatemala and separated from the Central American Union. The instability that followed the disintegration of the union led to the independence of the other Central American countries.

In Brazil, rural aristocrats were in conflict with the urban conservatives. Portuguese control over Brazilian ports continued after Brazil's independence. Following the conservative idea that the old government was better, urbanites tended to support conservatism because more opportunities were available to them as a result of the Portuguese presence.

Simón Bolívar became president of Gran Colombia in 1819 after the region gained independence from Spain. He led a military-controlled state. Citizens did not like the government's position under Bolívar: The people in the military were unhappy with their roles, and the civilians were of the opinion that the military had too much power. After the dissolution of Gran Colombia, New Grenada continued to have conflicts between conservatives and liberals. These conflicts were each concentrated in particular regions, with conservatives particularly in the southern mountains and the Valley of Cauca. In the mid-1840s some leaders in Caracas organized a liberal opposition. Antonio Leocadio Guzman was an active participant and journalist in this movement and gained much popularity among the people of Caracas.[53]

In Argentina, the conflict manifested itself as a prolonged civil war between unitarianas (i.e. centralists) and federalists, which were in some aspects respectively analogous to liberals and conservatives in other countries. Between 1832 and 1852, the country existed as a confederation, without a head of state, although the federalist governor of Buenos Aires province, Juan Manuel de Rosas, was given the powers of debt payment and international relations and exerted a growing hegemony over the country. A national constitution was only enacted in 1853, reformed in 1860, and the country reorganized as a federal republic led by a liberal-conservative elite.[54] After Uruguay achieved its independence, in 1828, a similar polarization crystallized between blancos and colorados, where the agrarian conservative interests were pitted against the liberal commercial interests based in Montevideo, and which eventually resulted in the Guerra Grande civil war (1839–1851).[55]

British influence in Latin America during the 19th century

Losing most of its North American colonies at the end of the 18th century left Great Britain in need of new markets to supply resources in the early 19th century.[56] In order to solve this problem, Great Britain turned to the Spanish colonies in South America for resources and markets. In 1806 a small British force surprise attacked the capitol of the viceroyalty in Río de la Plata.[57] As a result, the local garrison protecting the capitol was destroyed in an attempt to defend against the British conquest. The British were able to capture large amounts of precious metals, before a French naval force intervened on behalf of the Spanish King and took down the invading force. However, this caused much turmoil in the area as militia took control of the area from the viceroy. The next year the British attacked once again with a much larger force attempting to reach and conquer Montevideo.[58] They failed to reach Montevideo but succeeded in establishing an alliance with the locals. As a result, the British were able to take control of the Indian markets.

This newly gained British dominance hindered the development of Latin American industries and strengthened the dependence on the world trade network.[59] Britain now replaced Spain as the region's largest trading partner.[60] Great Britain invested significant capital in Latin America to develop the area as a market for processed goods.[61] From the early 1820s to 1850, the post-independence economies of Latin American countries were lagging and stagnant.[56] Eventually, enhanced trade among Britain and Latin America led to state development such as infrastructure improvements. These improvements included roads and railroads which grew the trades between countries and outside nations such as Great Britain.[62] By 1870, exports dramatically increased, attracting capital from abroad (including Europe and USA).[63]

French involvement in Latin America during the 19th century

Between 1821 and 1910, Mexico battled through various civil wars between the established Conservative government and the Liberal reformists ("Mexico Timeline- Page 2)". On May 8, 1827 Baron Damas, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Sebastián Camacho, a Mexican diplomat, signed an agreement called "The Declarations" which contained provisions regarding commerce and navigation between France and Mexico. At this time the French government did not recognize Mexico as an independent entity.[64] It was not until 1861 that the liberalist rebels, led by Benito Juárez, took control of Mexico City, consolidating liberal rule. However, the constant state of warfare left Mexico with a tremendous amount of debt owed to Spain, England, and France, all of whom funded the Mexican war effort (Neeno). As newly appointed president, Benito Juárez suspended payment of debts for next two years, to focus on a rebuilding and stabilization initiative in Mexico under the new government. On December 8, 1861, Spain, England and France landed in Veracruz to seize unpaid debts from Mexico. However, Napoleon III, with intentions of establishing a French client state to further push his economic interests, pressured the other two powers to withdraw in 1862 (Greenspan; "French Intervention in Mexico…").

France under Napoleon III remained and established Maximilian of Habsburg, Archduke of Austria, as Emperor of Mexico.[65] The march by the French to Mexico City enticed heavy resistance by the Mexican government, it resulted in open warfare. The Battle of Puebla in 1862 in particular presented an important turning point in which Ignacio Zaragoza led the Mexican army to victory as they pushed back the French offensive ("Timeline of the Mexican Revolution"). The victory came to symbolize Mexico's power and national resolve against foreign occupancy and as a result delayed France's later attack on Mexico City for an entire year (Cinco de Mayo (Mexican History)). With heavy resistance by Mexican rebels and the fear of United States intervention against France, forced Napoleon III to withdraw from Mexico, leaving Maximilian to surrender, where he would be later executed by Mexican troops under the rule of Porfirio Díaz.[66] Napoleon III's desire to expand France's economic empire influenced the decision to seize territorial domain over the Central American region. The port city of Veracruz, Mexico and France's desire to construct a new canal were of particular interest. Bridging both New World and East Asian trade routes to the Atlantic were key to Napoleon III's economic goals to the mining of precious rocks and the expansion of France's textile industry. Napoleon's fear of the United States' economic influence over the Pacific trade region, and in turn all New World economic activity, pushed France to intervene in Mexico under the pretense of collecting on Mexico's debt. Eventually France began plans to build the Panama Canal in 1881 until 1904 when the United States took over and proceeded with its construction and implementation ("Read Our Story").

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was included in President James Monroe's 1823 annual message to Congress. The doctrine warns European nations that the United States will no longer tolerate any new colonization of Latin American countries. It was originally drafted to meet the present major concerns, but eventually became the precept of U.S. foreign policy in the Western Hemisphere. The doctrine was put into effect in 1865 when the U.S. government supported Mexican president, Benito Juárez, diplomatically and militarily. Some Latin American countries viewed the U.S. interventions, allowed by the Monroe Doctrine when the U.S. deems necessary, with suspicion.[67]

Another important aspect of United States involvement in Latin America is the case of the filibuster William Walker. In 1855, he traveled to Nicaragua hoping to overthrow the government and take the land for the United States. With only the aid of 56 followers, he was able to take over the city of Granada, declaring himself commander of the army and installing Patricio Rivas as a puppet president. However, Rivas's presidency ended when he fled Nicaragua; Walker rigged the following election to ensure that he became the next president. His presidency did not last long, however, as he was met with much opposition from political groups in Nicaragua and neighbouring countries. On May 1, 1857, Walker was forced by a coalition of Central American armies to surrender himself to a United States Navy officer who repatriated him and his followers. When Walker subsequently returned to Central America in 1860, he was apprehended by the Honduran authorities and executed.

Mexican–American War (1846–48)

The Mexican–American War, another instance of U.S. involvement in Latin America, was a war between the United States and Mexico that started in April 1846 and lasted until February 1848. The main cause of the war was the United States' annexation of Texas in 1845 and a dispute afterwards about whether the border between Mexico and the United States ended where Mexico claimed, at the Nueces River, or ended where the United States claimed, at the Rio Grande. Peace was negotiated between the United States and Mexico with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which stated that Mexico was to cede land which would later become part of California and New Mexico as well as give up all claims to Texas, for which the United States would pay $15,000,000. However, tensions between the two countries were still high and over the next six years things only got worse with raids along the border and attacks by Native Americans against Mexican citizens. To defuse the situation, the United States agreed to purchase 29,670 squares miles of land from Mexico for $10,000,000 so a southern railroad could be built to connect the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. This would become known as the Gadsden Purchase. A critical component of U.S. intervention in Latin American affairs took form in the Spanish–American War, which drastically affected the futures of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Americas, as well as Guam and the Philippines, by acquiring the majority of the last remaining Spanish colonial possessions.

From the "Big Stick" to the "Good Neighbor" policy

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the U.S. banana importing companies United Fruit Company, Cuyamel Fruit Company (both ancestors of Chiquita), and Standard Fruit Company (now Dole), acquired large amounts of land in Central American countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and Costa Rica. The companies gained leverage over the governments and a ruling elite in these countries by dominating their economies and paying kickbacks, and exploited local workers. These countries came to be called banana republics.

Cubans, with the aid of Dominicans,[68] launched a war for independence in 1868 and, over the next 30 years, suffered 279,000 losses[69] in a brutal war against Spain that culminated in U.S. intervention. The 1898 Spanish–American War resulted in the end of Spanish colonial presence in the Americas. A period of frequent U.S. intervention in Latin America followed, with the acquisition of the Panama Canal Zone in 1903, the so-called Banana Wars in Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Honduras; the Caco Wars in Haiti; and the so-called Border War with Mexico. Some 3,000 Latin Americans were killed between 1914 and 1933.[70] The U.S. press described the occupation of the Dominican Republic as an 'Anglo-Saxon crusade', carried out to keep the Latin Americans 'harmless against the ultimate consequences of their own misbehavior'.[71]

After World War I, U.S. interventionism diminished, culminating in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy in 1933.

World wars (1914–1945)

World War I and the Zimmermann Telegram

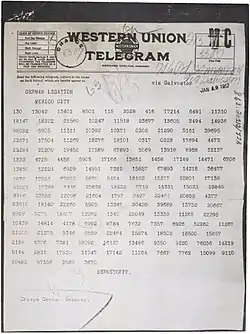

The Zimmermann Telegram was a 1917 diplomatic proposal from the German Empire for Mexico to join an alliance with Germany in the event of the United States entering World War I against Germany. The proposal was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence. The revelation of the contents outraged the American public and swayed public opinion. President Woodrow Wilson moved to arm American merchant ships to defend themselves against German submarines, which had started to attack them. The news helped generate support for the United States declaration of war on Germany in April of that year.[72]

The message came as a coded telegram dispatched by the Foreign Secretary of the German Empire, Arthur Zimmermann, on January 16, 1917. The message was sent to the German ambassador of Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. Zimmermann sent the telegram in anticipation of the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany on February 1, an act which Germany presumed would lead to war. The telegram instructed Ambassador Eckardt that if the U.S. appeared certain to enter the war, he was to approach the Mexican Government with a proposal for a military alliance, with funding from Germany. As part of the alliance, Germany would assist Mexico in reconquering Texas and the Southwest. Eckardt was instructed to urge Mexico to help broker an alliance between Germany and Japan. Mexico, in the middle of the Mexican Revolution, far weaker militarily, economically and politically than the U.S., ignored the proposal; after the U.S. entered the war, it officially rejected it.

Brazil's participation in World War II

After World War I, in which Brazil was an ally of the United States, Great Britain, and France, the country realized it needed a more capable army but did not have the technology to create it. In 1919, the French Military Mission was established by the French Commission in Brazil. Their main goal was to contain the inner rebellions in Brazil. They tried to assist the army by bringing them up to the European military standard but constant civil missions did not prepare them for World War II.

Brazil's President, Getúlio Vargas, wanted to industrialize Brazil, allowing it to be more competitive with other countries. He reached out to Germany, Italy, France, and the United States to act as trade allies. Many Italian and German people immigrated to Brazil many years before World War II began thus creating a Nazi influence. The immigrants held high positions in government and the armed forces.

Brazil continued to try to remain neutral to the United States and Germany because it was trying to make sure it could continue to be a place of interest for both opposing countries. Brazil attended continental meetings in Buenos Aires, Argentina (1936); Lima, Peru (1938); and Havana, Cuba (1940) that obligated them to agree to defend any part of the Americas if they were to be attacked. Eventually, Brazil decided to stop trading with Germany once Germany started attacking offshore trading ships resulting in Germany declaring a blockade against the Americas in the Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, Germany also ensured that they would be attacking the Americas soon.

Once the German submarines attacked unarmed Brazilian trading ships, President Vargas met with the United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss how they could retaliate. On January 22, 1942, Brazil officially ended all relations with Germany, Japan, and Italy, becoming a part of the Allies.

The Brazilian Expeditionary Force was sent to Naples, Italy to fight for democracy. Brazil was the only Latin American country to send troops to Europe. Initially, Brazil wanted to only provide resources and shelter for the war to have a chance of gaining a high postwar status but ended up sending 25,000 men to fight.[73]

However, it was not a secret that Vargas had an admiration for Hitler's Nazi Germany and its Führer. He even let German Luftwaffe build secret air forces around Brazil. This alliance with Germany became Brazil's second best trade alliance behind the United States.

It was recently found that 9,000 war criminals escaped to South America, including Croats, Ukrainians, Russians and other western Europeans who aided the Nazi war machine. Most, perhaps as many as 5,000, went to Argentina; between 1,500 and 2,000 are thought to have made it to Brazil; around 500 to 1,000 to Chile; and the rest to Paraguay and Uruguay.

After World War II, the United States and Latin America continued to have a close relationship. For example, USAID created family planning programs in Latin America combining the NGOs already in place, providing the women in largely Catholic areas access to contraception.[74]

Mexico and World War II

Mexico entered World War II in response to German attacks on Mexican ships. The Potrero del Llano, originally an Italian tanker, had been seized in port by the Mexican government in April 1941 and renamed in honor of a region in Veracruz. It was attacked and crippled by the German submarine U-564 on May 13, 1942. The attack killed 13 of 35 crewmen.[75] On May 20, 1942, a second tanker, Faja de Oro, also a seized Italian ship, was attacked and sunk by the German submarine U-160, killing 10 of 37 crewmen. In response, President Manuel Ávila Camacho and the Mexican government declared war on the Axis powers on May 22, 1942.

A large part of Mexico's contribution to the war came through an agreement January 1942 that allowed Mexican nationals living in the United States to join the American armed forces. As many as 250,000 Mexicans served in this way.[76] In the final year of the war, Mexico sent one air squadron to serve under the Mexican flag: the Mexican Air Force's Escuadrón Aéreo de Pelea 201 (201st Fighter Squadron), which saw combat in the Philippines in the war against Imperial Japan.[77] Mexico was the only Latin-American country to send troops to the Asia-Pacific theatre of the war. In addition to those in the armed forces, tens of thousands of Mexican men were hired as farm workers in the United States during the war years through the Bracero program, which continued and expanded in the decades after the war.[78]

World War II helped spark an era of rapid industrialization known as the Mexican Miracle.[79] Mexico supplied the United States with more strategic raw materials than any other country, and American aid spurred the growth of industry.[80] President Ávila was able to use the increased revenue to improve the country's credit, invest in infrastructure, subsidize food, and raise wages.[81]

World War II and the Caribbean

President Federico Laredo Brú led Cuba when war broke out in Europe, though real power belonged to Fulgencio Batista as Chief of Staff of the army.[82] In 1940, Laredo Brú infamously denied entry to 900 Jewish refugees who arrived in Havana aboard the MS St. Louis. After both the United States and Canada likewise refused to accept the refugees, they returned to Europe, where many were eventually murdered in the Holocaust.[83] Batista became president in his own right following the election of 1940. He cooperated with the United States as it moved closer to war against the Axis. Cuba declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, and on Germany and Italy on December 11.[84]

Cuba was an important participant in the Battle of the Caribbean and its navy gained a reputation for skill and efficiency. The navy escorted hundreds of Allied ships through hostile waters, flew thousands of hours on convoy and patrol duty, and rescued over 200 victims of German U-Boat attacks from the sea. Six Cuban merchant ships were sunk by U-boats, taking the lives of around eighty sailors. On May 15, 1943, a squadron of Cuban submarine chasers sank the German submarine U-176 near Cayo Blanquizal.[85] Cuba received millions of dollars in American military aid through the Lend-Lease program, which included air bases, aircraft, weapons, and training.[84] The United States naval station at Guantanamo Bay also served as a base for convoys passing between the mainland United States and the Panama Canal or other points in the Caribbean.[86]

The Dominican Republic declared war on Germany and Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Nazi declaration of war on the US. It did not directly contribute with troops, aircraft, or ships, however 112 Dominicans were integrated into the US military and fought in the war.[87] On May 3, 1942, German submarine U-125 sank Dominican ship San Rafael with 1 torpedo and 32 rounds from the deck gun 50 miles west off Jamaica; 1 was killed, 37 survived. On May 21, 1942, German submarine U-156 sank Dominican ship Presidente Trujillo off Fort-de-France, Martinique; 24 were killed, 15 survived.[88] Rumors of pro-Nazi Dominicans supplying German U-boats with food, water and fuel abounded during the war.[89]

Involvement in World War II

There was a Nazi influence in certain parts of the region, but Jewish migration from Europe during the war continued. Only a few people recognized or knew about the Holocaust.[90] Furthermore, numerous military bases were built during the war by the United States, but some also by the Germans. Even now, unexploded bombs from the second world war that need to be made safe still remain.[91]

The only international conflicts since World War II have been the Football War between El Salvador and Honduras (1969), the Cenepa War between Ecuador and Peru (1995), along with Argentina's war with the United Kingdom for control of the Falkland Islands (1982). The Falklands War left 649 Argentines (including 143 conscripted privates) dead and 1,188 wounded, while the UK lost 255 (88 Royal Navy, 27 Royal Marines, 16 Royal Fleet Auxiliary, 123 British Army, and 1 Royal Air Force) dead.

Cold War (1945–1992)

Economy

The Great Depression caused Latin America to grow at a slow rate, separating it from leading industrial democracies. The two world wars and U.S. Depression also made Latin American countries favor internal economic development, leading Latin America to adopt the policy of import substitution industrialization.[93] Countries also renewed emphasis on exports. Brazil began selling automobiles to other countries, and some Latin American countries set up plants to assemble imported parts, letting other countries take advantage of Latin America's low labor costs. Colombia began to export flowers, emeralds and coffee grains and gold, becoming the world's second-leading flower exporter.

Economic integration was called for, to attain economies that could compete with the economies of the United States or Europe. Starting in the 1960s with the Latin American Free Trade Association and Central American Common Market, Latin American countries worked toward economic integration.

In efforts to help regain global economic strength, the U.S. began to heavily assist countries involved in World War II at the expense of Latin America. Markets that were previously unopposed as a result of the war in Latin America grew stagnant as the rest of the world no longer needed their goods.

Reforms

Large countries like Argentina called for reforms to lessen the disparity of wealth between the rich and the poor, which has been a long problem in Latin America that stunted economic growth.[94]

Advances in public health caused an explosion of population growth, making it difficult to provide social services. Education expanded, and social security systems introduced, but benefits usually went to the middle class, not the poor. As a result, the disparity of wealth increased. Increasing inflation and other factors caused countries to be unwilling to fund social development programs to help the poor.

Bureaucratic authoritarianism

Bureaucratic authoritarianism was practised in Brazil after 1964, in Argentina, and in Chile under Augusto Pinochet, in a response to harsh economic conditions. It rested on the conviction that no democracy could take the harsh measures to curb inflation, reassure investors, and quicken economic growth quickly and effectively. Though inflation fell sharply, industrial production dropped with the decline of official protection.[94]

US relations

After World War II and the beginning of a Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, US diplomats became interested in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and frequently waged proxy wars against the Soviet Union in these countries. The US sought to stop the spread of communism. Latin American countries generally sided with the US in the Cold War period, even though they were neglected since the US's concern with communism were focused in Europe and Asia, not Latin America. Between 1946 and 1959 Latin America received only 2% of the United States foreign aid despite having poor conditions similar to the main recipients of The Marshall Plan.[95] Some Latin American governments also complained of the US support in the overthrow of some nationalist governments, and intervention through the CIA. In 1947, the US Congress passed the National Security Act, which created the National Security Council in response to the United States's growing obsession with anti-communism.[96] In 1954, when Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala accepted the support of communists and attacked holdings of the United Fruit Company, the US decided to assist Guatemalan counter-revolutionaries in overthrowing Arbenz.[97] These interventionist tactics featured the use of the CIA rather than the military, which was used in Latin America for the majority of the Cold War in events including the overthrow of Salvador Allende. Latin America was more concerned with issues of economic development, while the United States focused on fighting communism, even though the presence of communism was small in Latin America.[96]

Dominican dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo (r. 1930–61) achieved support from the US by becoming Latin America's leading anti-communist.[98] Trujillo extended his tyranny to the USA,[99][100] and his regime committed multiple murders in New York City.[101] American officials had long recognized that the Dominican Republic's conduct under Trujillo was "below the level of recognized civilian nations, certainly not much above that of the communists." But after Castro's seizure of power in 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower concluded that Trujillo had become a Cold War liability.[100] In 1960, Trujillo threatened to align with the Communist world in response to US and Latin American rejection of his regime. La Voz Dominicana and Radio Caribe began attacking the US in Marxian terms, and the Dominican Communist party was legalized. Trujillo also unsuccessfully attempted to establish contacts and relations with the Soviet Bloc.[102] In 1961, Trujillo was murdered with weapons supplied by the CIA.[103] Ramfis Trujillo, the dictator's son, remained in de facto control of the government for the next six months through his position as commander of the armed forces. Trujillo's brothers, Hector Bienvenido and Jose Arismendi Trujillo, returned to the country and began immediately to plot against President Balaguer. On November 18, 1961, as a planned coup became more evident, US Secretary of State Dean Rusk issued a warning that the United States would not "remain idle" if the Trujillos attempted to "reassert dictatorial domination" over the Dominican Republic. Following this warning, and the arrival of a fourteen-vessel US naval task force within sight of Santo Domingo, Ramfis and his uncles fled the country on November 19 with $200 million from the Dominican treasury.

Cuban Revolution

By 1959, Cuba was afflicted with a corrupt dictatorship under Batista, and Fidel Castro ousted Batista that year and set up the first communist state in the hemisphere. The United States imposed a trade embargo on Cuba, and combined with Castro's expropriation of private enterprises, this was detrimental to the Cuban economy.[93] Around Latin America, rural guerrilla conflict and urban terrorism increased, inspired by the Cuban example. The United States put down these rebellions by supporting Latin American countries in their counter-guerrilla operations through the Alliance for Progress launched by President John F. Kennedy. This thrust appeared to be successful. A Marxist, Salvador Allende, became president of Chile in 1970, but was overthrown three years later in a military coup backed by the United States. Despite civil war, high crime and political instability, most Latin American countries eventually adopted bourgeois liberal democracies while Cuba maintained its socialist system.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

Encouraged by the success of Guatemala in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état,[104] in 1960, the U.S. decided to support an attack on Cuba by anti-Castro rebels. The Bay of Pigs invasion was an unsuccessful invasion of Cuba in 1961, financed by the U.S. through the CIA, to overthrow Fidel Castro. The incident proved to be very embarrassing for the new Kennedy administration.[105]

The failure of the invasion led to a Soviet-Cuban alliance.

Cuban Missile Crisis

In 1962, Cuba threatened the USA when it allowed Soviet missiles to be placed on the island, just 90 miles away from Florida; Cuba saw it as a way to defend the island, while the Americans saw it as a threat. The ensuing Cuban Missile Crisis—the closest the world has ever come to total annihilation—almost saw a US invasion or bombing of Cuba, but it ended when the two sides agreed on the removal of missiles; the US removed theirs from Italy and Turkey, while the Soviets removed theirs from Cuba. The crisis' end left Cuba blockaded by the US, which was also obligated to not invade Cuba. In fact, they were allowed to keep Guantanamo Bay as a naval base as per an agreement with the previous government of Batista.

Alliance for Progress

President John F. Kennedy initiated the Alliance for Progress in 1961, to establish economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America. The Alliance would provide $20 billion for reform in Latin America, and counterinsurgency measures. Instead, the reform failed because of the simplistic theory that guided it and the lack of experienced American experts who could understand Latin American customs.[106]

Foreign interventions by Cuba

Armed Cuban intervention overseas began on June 14, 1959 with an invasion of the Dominican Republic[107] by a group of fifty-six men, who landed a C-56 transport aircraft at the military airport of the town of Constanza. Upon their landing, the fifteen-man Dominican garrison began an ongoing gun battle with the invaders, until the survivors disappeared into the surrounding mountains. Immediately after, the Dominican Air Force bombed the area around Constanza with British made Vampire jets in an unsuccessful attempt to kill the invaders, which instead killed civilians.[108] The invaders either died at the hands of machete-swinging peasants,[109] or the military captured, tortured, and imprisoned them. A week later, two yachts offloaded 186 invaders onto Chris-Craft launches for a landing on the north coast. Dominican Air Force pilots fired rockets from their Vampire jets into the approaching launches, killing most of the invaders. The survivors were brutally tortured and murdered.

From 1966 until the late 1980s, the Soviet government upgraded Cuba's military capabilities, and Castro saw to it that Cuba assisted with the independence struggles of several countries across the world, most notably Angola and Mozambique in southern Africa, and the anti-imperialist struggles of countries such as Syria, Algeria, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Vietnam.[110][107]

South Africa developed nuclear weapons due to the threat to its security posed by the presence of large numbers of Cuban troops in Angola and Mozambique.[111] In November 1975, Cuba poured more than 65,000 troops into Angola in one of the fastest military mobilizations in history.[112] On November 10, 1975, Cuban forces defeated the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) in the Battle of Quifangondo. On November 25, 1975, as the South African Defence Force (SADF) tried to cross a bridge, Cubans hidden along the banks of the river attacked, destroying seven armored cars and killing upwards of 90 enemy soldiers. On March 27, 1976, the last South African troops withdrew from Angola. In September 1977, 12 MiG-21s conducted strafing flights over Puerto Plata in Dominican Republic to warn then president Joaquín Balaguer against intercepting Cuban warships headed to or returning from Angola.[113][114] In 1988, Cuba returned to Angola with a vengeance. The crisis began in 1987 with an assault by Soviet-equipped national army troops against the pro-Western rebel movement UNITA in southeastern Angola. Soon, the SADF invaded to support the beleaguered US-backed faction and the Angolan offensive stalled. Cuba reinforced its African ally with 55,000 troops, tanks, artillery and MiG-23s, prompting Pretoria to call up 140,000 reservists.[115] In June 1988, SADF armor and artillery engaged FAPLA-Cuban forces at Techipa, killing 290 Angolans and 10 Cubans.[116] In retaliation, Cuban warplanes hammered South African troops.[115] However, both sides quickly pulled back to avoid an escalation of hostilities.[115] The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale stalemated, and a peace treaty was signed in September 1988. Within two years, the Cold War was over and Cuba's foreign policy shifted away from military intervention.

Nicaraguan Revolution

Following the American occupation of Nicaragua in 1912, as part of the Banana Wars, the Somoza family political dynasty came to power, and would rule Nicaragua until their ouster in 1979 during the Nicaraguan Revolution. The era of Somoza family rule was characterized by strong U.S. support for the government and its military as well as a heavy reliance on U.S.-based multi-national corporations. The Nicaraguan Revolution (Spanish: Revolución Nicaragüense or Revolución Popular Sandinista) encompassed the rising opposition to the Somoza dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s, the campaign led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) to violently oust the dictatorship in 1978–79, the subsequent efforts of the FSLN to govern Nicaragua from 1979 until 1990 and the Contra War which was waged between the FSLN and the Contras from 1981 to 1990.

The Revolution marked a significant period in Nicaraguan history and revealed the country as one of the major proxy war battlegrounds of the Cold War with the events in the country rising to international attention. Although the initial overthrow of the Somoza regime in 1978–79 was a bloody affair, the Contra War of the 1980s took the lives of tens of thousands of Nicaraguans and was the subject of fierce international debate.[117] During the 1980s both the FSLN (a leftist collection of political parties) and the Contras (a rightist collection of counter-revolutionary groups) received large amounts of aid from the Cold War super-powers (respectively, the Soviet Union and the United States).

Washington Consensus

The set of specific economic policy prescriptions that were considered the "standard" reform package were promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.-based institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and the US Department of the Treasury during the 1980s and 1990s.

In recent years, several Latin American countries led by socialist or other left wing governments – including Argentina and Venezuela – have campaigned for (and to some degree adopted) policies contrary to the Washington Consensus set of policies. (Other Latin countries with governments of the left, including Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Peru, have in practice adopted the bulk of the policies.) Also critical of the policies as actually promoted by the International Monetary Fund have been some US economists, such as Joseph Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik, who have challenged what are sometimes described as the "fundamentalist" policies of the International Monetary Fund and the US Treasury for what Stiglitz calls a "one size fits all" treatment of individual economies.

The term has become associated with neoliberal policies in general and drawn into the broader debate over the expanding role of the free market, constraints upon the state, and US influence on other countries' national sovereignty.

This politico-economical initiative was institutionalized in North America by 1994 NAFTA, and elsewhere in the Americas through a series of like agreements. The comprehensive Free Trade Area of the Americas project, however, was rejected by most South American countries at the 2005 4th Summit of the Americas.

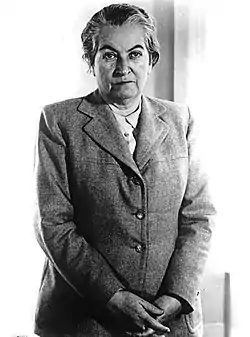

Turn to the left

In most countries, since the 2000s left-wing political parties have risen to power. The presidencies of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet in Chile, Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, Néstor Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernández in Argentina, Tabaré Vázquez and José Mujica in Uruguay, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay, Manuel Zelaya in Honduras (removed from power by a coup d'état), Mauricio Funes and Salvador Sánchez Cerén in El Salvador are all part of this wave of left-wing politicians who often declare themselves socialists, Latin Americanists, or anti-imperialists (often implying opposition to US policies towards the region). A development of this has been the creation of the eight-member ALBA alliance, or "The Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America" (Spanish: Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América) by some of the countries already mentioned. By June 2014, Honduras (Juan Orlando Hernández), Guatemala (Otto Pérez Molina), and Panama (Ricardo Martinelli) had right-wing governments.

Return of social movements

In 1982, Mexico announced that it could not meet its foreign debt payment obligations, inaugurating a debt crisis that would "discredit" Latin American economies throughout the decade.[118] This debt crisis would lead to neoliberal reforms that would instigate many social movements in the region. A "reversal of development" reigned over Latin America, seen through negative economic growth, declines in industrial production, and thus, falling living standards for the middle and lower classes.[119] Governments made financial security their primary policy goal over social security, enacting new neoliberal economic policies that implemented privatization of previously national industries and informalization of labor.[118] In an effort to bring more investors to these industries, these governments also embraced globalization through more open interactions with the international economy.

Significantly, as democracy spread across much of Latin America, the realm of government became more inclusive (a trend that proved conducive to social movements), the economic ventures remained exclusive to a few elite groups within society. Neoliberal restructuring consistently redistributed income upward while denying political responsibility to provide social welfare rights, and though development projects took place throughout the region, both inequality and poverty increased.[118] Feeling excluded from these new projects, the lower classes took ownership of their own democracy through a revitalization of social movements in Latin America.

Both urban and rural populations had serious grievances as a result of the above economic and global trends and have voiced them in mass demonstrations. Some of the largest and most violent of these have been protests against cuts in urban services, such as the Caracazo in Venezuela and the Argentinazo in Argentina.[120]

Rural movements have made diverse demands related to unequal land distribution, displacement at the hands of development projects and dams, environmental and indigenous concerns, neoliberal agricultural restructuring, and insufficient means of livelihood. These movements have benefited considerably from transnational support from conservationists and INGOs. The Movement of Rural Landless Workers (MST) is perhaps the largest contemporary Latin American social movement.[120] As indigenous populations are primarily rural, indigenous movements account for a large portion of rural social movements, including the Zapatista rebellion in Mexico, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), indigenous organizations in the Amazon region of Ecuador and Bolivia, pan-Mayan communities in Guatemala, and mobilization by the indigenous groups of Yanomami peoples in the Amazon, Kuna peoples in Panama, and Altiplano Aymara and Quechua peoples in Bolivia.[120] Other significant types of social movements include labor struggles and strikes, such as recovered factories in Argentina, as well as gender-based movements such as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina and protests against maquila production, which is largely a women's issue because of how it draws on women for cheap labor.[120]

Modern era

The 2000s commodities boom caused positive effects for many Latin American economies. Another trend is the rapidly increasing importance of the relations with China.[121]

With the end of the commodity boom in the 2010s, economic stagnation or recession resulted in some countries. As a result, the left-wing governments of the Pink Tide lost support. The worst-hit was Venezuela, which is facing severe social and economic upheaval.

The corruption scandal of Odebrecht, a Brazilian conglomerate, has raised allegations of corruption across the region's governments (see Operation Car Wash). The bribery ring has become the largest corruption scandal in Latin American history.[122] As of July 2017, the highest ranking politicians charged were former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (arrested)[123] and former Peruvian presidents Ollanta Humala (arrested) and Alejandro Toledo (fugitive, fled to the US).[124]

The COVID-19 pandemic proved a political challenge for many unstable Latin American democracies, with scholars identifying a decline in civil liberties as a result of opportunistic emergency powers. This was especially true for countries with strong presidential regimes, such as Brazil.[125]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1750 | 16,000,000 | — |

| 1800 | 24,000,000 | +50.0% |

| 1850 | 38,000,000 | +58.3% |

| 1900 | 74,000,000 | +94.7% |

| 1950 | 167,000,000 | +125.7% |

| 1999 | 511,000,000 | +206.0% |

| 2013 | 603,191,486 | +18.0% |

| Source: "UN report 2004 data" (PDF) | ||

Largest cities

The following is a list of the ten largest metropolitan areas in Latin America.[5]

| City | Country | 2017 population | 2014 GDP (PPP, $million, USD) | 2014 GDP per capita, (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico City | 23,655,355 | $403,561 | $19,239 | |

| São Paulo | 23,467,354 | $430,510 | $20,650 | |

| Buenos Aires | 15,564,354 | $315,885 | $23,606 | |

| Rio de Janeiro | 14,440,345 | $176,630 | $14,176 | |

| Lima | 10,804,609 | $176,447 | $16,530 | |

| Bogotá | 9,900,800 | $199,150 | $19,497 | |

| Santiago | 7,164,400 | $171,436 | $23,290 | |

| Belo Horizonte | 6,145,800 | $95,686 | $17,635 | |

| Guadalajara | 4,687,700 | $80,656 | $17,206 | |

| Monterrey | 4,344,200 | $122,896 | $28,290 |

Ethnic groups

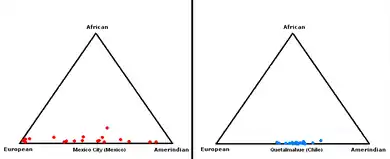

The inhabitants of Latin America are of a variety of ancestries, ethnic groups, and races, making the region one of the most diverse in the world. The specific composition varies from country to country: some have a predominance of European-Amerindian or more commonly referred to as Mestizo or Castizo depending on the admixture, population; in others, Amerindians are a majority; some are dominated by inhabitants of European ancestry; and some countries' populations are primarily Mulatto. Various black, Asian and Zambo (mixed black and Amerindian) minorities are also identified regularly. People with European ancestry are the largest single group, and along with people of part-European ancestry, they combine to make up approximately 80% of the population,[127] or even more.[128]

According to Jon Aske:

Before Hispanics became such a 'noticeable' group in the U.S., the distinction between black and white was the major racial division and according to the one-drop rule adhered to by the culture at large, one drop of African ancestry usually meant that the person was Black. ...

The notion of racial continuum and a separation of race (or skin color) and ethnicity, on the other hand, is the norm in most of Latin America. In the Spanish and Portuguese empires, racial mixing or miscegenation was the norm and something that the Spanish and Portuguese had grown rather accustomed to during the hundreds of years of contact with Arabs and North Africans in the Iberian peninsula. But, demographics may have made this inevitable as well. Thus, for example, of the approximately 13.5 million people who lived in the Spanish colonies in 1800 before independence only about one fifth were white. This contrasts with the U.S., where more than four-fifths were whites (out of a population of 5.3 million in 1801, 900,000 were slaves, plus approximately 60,000 free blacks). ...

The fact of the recognition of a racial continuum in Hispanic American (sic) does not mean that there wasn't discrimination, which there was, or that there wasn't an obsession with race, or 'castes', as they were sometimes called. ...

In areas with large indigenous Amerindian populations, a racial mixture resulted, which is known in Spanish as mestizos ... who are a majority in Mexico, Central America and most of South America. Similarly, when African slaves were brought to the Caribbean region and Brazil, where there was very little indigenous presence left, unions between them and Spanish produced a population of mixed mulatos ... who are a majority of the population in many of those Spanish-speaking Caribbean basin countries (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Colombia, and Venezuela).

Aske has also written that:

Spanish colonization was rather different from later English, or British, colonization of North America. They had different systems of colonization and different methods of subjugation. While the English were primarily interested in grabbing land, the Spanish in addition had a mandate to incorporate the land's inhabitants into their society, something which was achieved by religious conversion and sexual unions which produced a new 'race' of mestizos, a mixture of Europeans and indigenous peoples. mestizos (sic) form the majority of the population in Mexico, Central America, and much of South America. Racial mixing or miscegenation, after all, was something that the Spanish and Portuguese had been accustomed to during the hundreds of years of contact with Arabs and North Africans. Similarly, later on, when African slaves were introduced into the Caribbean basin region, unions between them and Spaniards produced a population of mulatos, who are a majority of the population in the Caribbean islands (the Antilles) (Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico), as well as other areas of the Caribbean region (Colombia, Venezuela and parts of the Central American Caribbean coast). mestizos (sic) and mulatos may not have always have been first class citizens in their countries, but they were never disowned in the way the outcomes of unions of Europeans and Native Americans were in the British colonies, where interracial marriages were taboo and one drop of Black or Amerindian blood was enough to make the person 'impure'.

In his famous 1963 book The Rise of the West, William Hardy McNeill wrote that:

Racially mixed societies arose in most of Spanish and Portuguese America, compounded in varying proportions from European, Indian, and Negro strands. Fairly frequent resort to manumission mitigated the hardships of slavery in those areas; and the Catholic church positively encouraged marriages between white immigrants and Indian women as a remedy for sexual immorality. However, in the southern English colonies and in most of the Caribbean islands, the importation of Negro slaves created a much more sharply polarized biracial society. Strong race feeling and the servile status of nearly all Negroes interdicted intermarriage, practically if not legally. Such discrimination did not prevent interbreeding; but children of mixed parentage were assigned to the status of their mothers. Mulattoes and Indian half-breeds were thereby excluded from the white community. In Spanish (and, with some differences, Portuguese) territories a more elaborate and less oppressive principle of racial discrimination established itself. The handful of persons who had been born in the homelands claimed topmost social prestige; next came those of purely European descent; while beneath ranged the various racial blends to form a social pyramid whose numerous racial distinctions meant that no one barrier could become as ugly and inpenetrable as that dividing whites from Negroes in the English, Dutch, and French colonies.

Thomas C. Wright, meanwhile, has written that: