Median umbilical ligament

The median umbilical ligament is an unpaired ligamentous structure in human anatomy. It is covered by the median umbilical fold.

| Median umbilical ligament | |

|---|---|

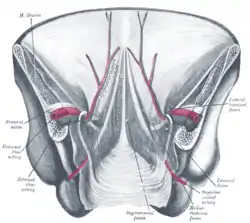

Posterior view of the anterior abdominal wall in its lower half. The peritoneum is in place, and the various cords are shining through. Median umbilical ligament isn't labeled, but it is located just underneath the median umbilical fold, seen in the center of the diagram | |

| Details | |

| From | Apex of urinary bladder |

| To | umbilicus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Ligamentum umbilicale medianum, ligamentum suspensorium vesicae urinariae |

| TA98 | A08.3.01.007 |

| TA2 | 4322 |

| FMA | 16568 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

It extends from the apex of the bladder to the umbilicus, on the deep surface of the anterior abdominal wall.[1][2][3] It is a fibrous piece of tissue that represents the remnant of the fetal urachus.[1][2]

Lateral to this structure are the medial umbilical ligament and the lateral umbilical ligament.

Function

The median umbilical ligament has no known function.[3]

Clinical significance

The median umbilical ligament may be used as a landmark for surgeons who are performing laparoscopy, such as laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Other than this, it has no function in a born human and may be cut or removed with impunity.

It contains the urachus, which is the obliterated form of the allantois. The allantois forms a communication between the cloaca (terminal part of hindgut) and the amniotic sac during embryonic development. If the urachus fails to close during fetal life, it can result in anatomical abnormalities such as a urachal cyst, urachal fistula, urachal diverticulum or urachal sinus.

Society and culture

The median umbilical ligament was jokingly referred to as "Xander's ligament" in a YouTube video, and this name was subsequently used on Wikipedia for a short time.[4] This term was later used in a paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.[4][5][6]

References

- Tan C, Simon MA, Dolin N, Gesner L (August 2020). "Incidental vesicourachal diverticulum in a young female". Radiology Case Reports. 15 (8): 1305–1308. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2020.05.046. PMC 7322240. PMID 32612730.

- Mrad Daly K, Ben Rhouma S, Zaghbib S, Oueslati A, Gharbi M, Nouira Y (September 2019). "Infected urachal cyst in an adult: A case report". Urology Case Reports. 26: 100976. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2019.100976. PMC 6661533. PMID 31380223.

- "Urachal anomalies: A review of pathological conditions, diagnosis, and management". Translational Research in Anatomy. 16: 100041. 2019-09-01. doi:10.1016/j.tria.2019.100041. ISSN 2214-854X.

- Wilson C. "This YouTuber Made Up A Name For A Body Part. It Ended Up In A Peer-Reviewed Medical Journal". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

- Giridhar KV, Kohli M (October 2017). "Management of Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Cancer and the Emerging Role of Immunotherapy in Advanced Urothelial Cancer". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 92 (10): 1564–1582. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.07.010. PMID 28982487.

- Ledger T, Toftness A (August 2020). "The Xander ligament? Caution advised when using online encyclopaedias". Journal of Anatomy. 237 (2): 391. doi:10.1111/joa.13195. PMC 7369185. PMID 32255503.

External links

- Median umbilical ligament

- Anatomy figure: 36:01-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The inguinal canal and derivation of the layers of the spermatic cord."

- Anatomy photo:44:04-0105 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: The Urinary Bladder"

- Anatomy image:7576 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Median umbilical fold

- Anatomy figure: 36:03-12 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Internal surface of the anterior abdominal wall."