Member states of the Caribbean Community

A member state of the Caribbean Community is a state that has been specified as a member state within the Treaty of Chaguaramas or any other Caribbean state that is in the opinion of the Conference, able and willing to exercise the rights and assume the obligations of membership in accordance with article 29 of the Treaty of Chaguaramas. Member states are designated as either More economically developed country (MDCs) or Less economically developed countries (LDCs). These designations are not intended to create disparity among member states.[1] The Community was established by mainly English-speaking Caribbean countries, but has since become a multilingual organisation in practice with the addition of Dutch-speaking Suriname in 1995 and French-speaking Haiti in 2002. There are fifteen full members of the Caribbean Community, four of which are founding members.

List

| Flag | State | Joined | Population | Area | GDP (PPP) $Million |

GDP (PPP) per capita |

HDI (2018) |

Currency | Official Language(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | mi2 | |||||||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 4 July 1974 | 94,731 | 442.6 | 170.9 | $2,390 | $26,300 | 0.776 | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Bahamas | 4 July 1983 | 329,988 | 10,010 | 3,860 | $9,339 | $25,100 | 0.805 | Bahamian Dollar | English | |

| Barbados | 1 August 1973 (Founder) | 292,336 | 430 | 170 | $4,919 | $17,500 | 0.813 | Barbadian Dollar | English | |

| Belize | 1 May 1974 | 360,346 | 22,806 | 8,805 | $3,230 | $8,300 | 0.720 | Belize Dollar | English | |

| Dominica | 1 May 1974 | 73,897 | 751 | 290 | $851 | $12,000 | 0.724 | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Grenada | 1 May 1974 | 111,724 | 344 | 133 | $1,590 | $14,700 | 0.763 | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Guyana | 1 August 1973 (Founder) | 737,718 | 196,849 | 76,004 | $6,367 | $8,300 | 0.670 | Guyanese Dollar | English | |

| Haiti | 2 July 2002 | 10,646,714 | 27,560 | 10,640 | $19,880 | $1,800 | 0.503 | Haitian Gourde | French and Haitian Creole | |

| Jamaica | 1 August 1973 (Founder) | 2,990,561 | 10,831 | 4,182 | $26,200 | $9,200 | 0.726 | Jamaican Dollar | English | |

| Montserrat | 1 May 1974 | 5,292 | 102 | 39 | $43.78 | $8,500 | - | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 26 July 1974 | 52,715 | 261 | 101 | $1,288 | $26,800 | 0.777 | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Saint Lucia | 1 May 1974 | 164,994 | 606 | 234 | $2,384 | $13,500 | 0.745 | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 1 May 1974 | 102,089 | 389 | 150 | $1,281 | $11,600 | 0.728 | East Caribbean Dollar | English | |

| Suriname | 4 July 1995 | 591,919 | 156,000 | 60,000 | $7,928 | $13,900 | 0.724 | Surinamese dollar | Dutch | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 August 1973 (Founder) | 1,218,200 | 5,128 | 1,980 | $42,780 | $31,200 | 0.799 | Trinidad and Tobago Dollar | English | |

| Highest | |

| Lowest |

Anguilla

In July 1999, Anguilla once again became involved with CARICOM when it gained associate membership. Before this, Anguilla had briefly been a part of CARICOM (1974–1980) as a constituent of the full member state of Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla.

The Bahamas (1973-1983)

The Bahamas had begun participating in the regional cooperation and integration movement when it began attending the Heads of Government Conferences of the Commonwealth Caribbean in 1966. This practice continued even after the establishment of CARIFTA, of which The Bahamas was never a member, with The Bahamas being involved in educational cooperation and Committees established to deepen financial cooperation among CARIFTA states and the Bahamas and to transform CARIFTA into the Caribbean Community. In particular, The Bahamas was even included in a Committee of Attorneys-General tasked with examining the legal implications of forming the Caribbean Community and to draw up a draft Treaty for its formation. In April 1973, at the final meeting of the commonwealth Caribbean Heads of Government before the establishment of the Caribbean Community, the Conference welcomed the upcoming independence of The Bahamas in July 1973 and looked forward to its participation in the Caribbean Community.[2] In late 1974, the Bahamas (as well as Haiti and Suriname) indicated that it would like to join the Community.[3] Bahamian involvement with the Caribbean Community and regional integration continued in the same form after independence and the establishment of CARICOM as had occurred since 1966, with The Bahamas attending the second meeting of the CARICOM Heads of Government Conference in 1975 and being involved in the setting up of a special Inter-Governmental Committee on university education.[4] In fact, the original Treaty of Chaguaramas (In Chapter I, Article 2) provided for The Bahamas to automatically join the Caribbean Community and Common Market upon application,[5] with the Bahamas being listed alongside the actual member states as being a state to which membership of the Community may be open to.[1] The final Conference of the Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community and The Bahamas at which this informal participation by The Bahamas continued was November 1982 Conference in Jamaica.[6] At the next Conference, The Bahamas was formally admitted as a member of the Community.[7]

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic cooperates with CARICOM (since 1992) under an umbrella organisation, CARIFORUM, an economic pact between CARICOM and the Dominican Republic with the EU.[8] The Dominican Republic became an Observer of CARICOM in 1982 and in 1991 it presented CARICOM with a request for full membership,[9] having first given consideration to joining the bloc in 1989.[10] It also has an unratified free trade agreement (from 2001) with CARICOM. Within the EPA between the region and the European Commission, the Dominican Republic is given means for dispute resolution with CARICOM member-states. Under Article 234, the European Court of Justice also carries dispute resolution mechanisms between CARIFORUM and the European Union states.[11] This is particularly useful to the Dominican Republic which is not a member of the Caribbean Court of Justice and therefore cannot use the CCJ for dispute resolution with states of CARICOM.

In 2005 the Foreign Minister of the Dominican Republic proposed for the second time that the government of the Dominican Republic wished to obtain full membership status in CARICOM. However, due to the sheer size of the Dominican Republic's population and its economy being almost as large as all the current CARICOM states combined and coupled with the Dominican Republic's checkered history of foreign policy solidarity with the CARICOM states, it is unclear whether the CARICOM states will unanimously vote to admit the Dominican Republic as a full member into the organisation. CARICOM has been working at great pains in trying to integrate with Haiti. It has been proposed that CARICOM may deepen ties with the Dominican Republic through the auspice of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS) instead, which is an organisation that stops just short of the Single market and economy which underpins CARICOM.

In July 2013, The President of the Dominican Republic, Danilo Medina, indicated that his country was still interested in joining CARICOM and appealed to CARICOM leaders meeting in Trinidad for the 40th anniversary of CARICOM to admit his country into the organization.[12] His bid drew the support of Trinidad and Tobago's Prime Minister and the then Chairwoman of CARICOM, Kamla Persad-Bissessar, who addressed the others CARICOM heads of government by saying “The ongoing reform process in the community must be one that will make CARICOM not only more efficient and effective but more relevant as well. In this regard, may I urge you to consider expanding our membership to welcome the Dominican Republic into the CARICOM family.” It is not clear whether the CARICOM Heads of Government will agree, but the move could prove critical as the Dominican Republic increasingly allies itself both with Latin America and Central America, having become a full member state of the Central American Integration System in late June 2013 (it was previously an associate member).[13] The call for the Dominican Republic to be admitted as a full member of CARICOM was given a boost by the position of the Prime Minister of Barbados, Freundel Stuart, who confirmed that the Dominican Republic was re-committed “to joining the movement at such time that it would be convenient for all the perceivable imperatives to be satisfied,” and that “I agree with the Prime Minister that the larger the bloc becomes, the more powerful the bloc becomes and the more diversified the areas for joint action and for integration.” Stuart also remarked that it was a healthy development when Suriname and Haiti joined the movement and that the Heads of Government want to quicken the momentum in the expansion of CARICOM to countries without British heritage.[14]

In November 2013, CARICOM announced that it would "suspend consideration of the request by the Dominican Republic for membership of the Caribbean Community" in response to a Dominican court ruling which revoked citizenship from tens of thousands, mostly descendants from illegal immigrants from Haiti.[15][16]

French West Indies

The French Republic extends to several islands in the Caribbean that are not associated with CARICOM, and are instead part of the European Union: Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint-Martin, Saint Barthélemy and French Guiana. The CARICOM-DR-EU Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) presently provides these areas with access to CARICOM markets. It was announced during summer of 2012 that the outer region area of Martinique, was pushing for France to become an Associate Member. Trepubhe Foreign Minister of France, Laurent Fabius, agreed to France being an associate member of CARICOM. At the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the Heads of Government Conference in July 2013, the Heads of Government received the report of the Technical Working Group (TWG) established to review and provide recommendations on the terms and conditions of Membership and Associate Membership of the Community. They also agreed that the applications for Associate Membership of France (French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique) and the Kingdom of the Nertherlands (Curaçao and St. Maarten), would require further deliberation at the level of Heads of Government.[17]

In January 2015, it was reported that representatives of the French Republic had begun discussion with CARICOM on their application for associate membership. Teams from French Guiana (led by the President of the French Guiana Regional Council, Rodolphe Alexandre) and from Martinique met with CARICOM's Secretary-General Irwin LaRocque on 22 January 2015 and 21 January 2015 respectively. A team from Guadeloupe is due to hold similar discussion in February 2015.[18]

The discussions focused on regional cooperation, the terms and conditions for associate membership and the overall relation between the French Republic and CARICOM. Rodolphe Alexandre said that support in French Guiana strongly agreed with convergence of the Caribbean in health, climate change, education, economics and issues of bio-diversity. He also noted that French Guiana had already engaged with individual Community member states on issues related to mining (in this case, with Suriname) and energy (Trinidad & Tobago).[18]

Haiti (1974-2002)

The first attempt by Haiti to join CARICOM began on 6 May 1974, when Haiti officially applied for membership in the Community[19] after Edner Brutus, the Haitian Minister of Foreign Affairs, sent a letter to William Demas, CARICOM's Secretary-General formally applying for membership.[20] Shortly after that request, Haiti lobbied for admission, dealing mostly with Percival J. Patterson, then Jamaica's minister of industry, commerce, and tourism. Patterson welcomed the initiative and promised Jamaica's unconditional support. Despite Patterson's efforts, the CARICOM secretariat did not respond positively to the request, and CARICOM leadership decided to pursue a special type of relationship with Haiti.[19] Haiti was later accepted as an observer[19] in 1982 [21] following an application for closer relations with the Community.[6] On July 3, 1997, almost 25 years later, CARICOM chairman and Prime Minister of Jamaica Percival J. Patterson announced that Haiti was to become the fifteenth member country of CARICOM[19] after the Heads of Government, in accordance with Article 29 of the (Original) Treaty of Chaguaramas had unanimously agreed to it.[22] This announcement was made alongside Haitian President René Préval at an unscheduled joint press conference in Montego Bay, Jamaica. Technically, Haiti had joined the Caribbean Community but not the common market (similar to The Bahamas' membership). It was later announced that, in accordance with Article 29(2) of the Treaty of Chaguaramas,[22] a CARICOM technical working group would visit Haiti to consult with the Haitian government on the terms and conditions of full membership in CARICOM. The decision to admit Haiti raised a host of technical issues, including Haiti's CARICOM dues, the extent to which French would also become an official language of CARICOM, and the extent to which existing CARICOM provisions allowing for the unfettered movement of member nationals would apply to Haiti. In the interim, Haiti was invited to participate in the deliberations of CARICOM's organs and bodies.[19][22]

At the Twentieth Heads of Government meeting, in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, the Heads of Government and Haiti exchanged notes agreeing on the terms and conditions under which Haiti would accede to Membership of the Community. The Heads of Government looked forward to the early deposit of an Instrument of Accession by Haiti to the Treaty of Chaguaramas.[23]

In preparation for the finalization of Haiti's membership of the Community, in February 2001 at the Twelfth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government held in Barbados,[24] the Conference emphasised the necessity for Haiti to adhere, as is required of all Community Member States, to the Charter of Civil Society, and in keeping with Haiti's undertaking as a condition of its Terms of Accession to the Caribbean Community[25] The Conference also agreed at the invitation of President Aristide, to explore the possibility of a joint CARICOM/International Mission to Haiti and decided to establish a CARICOM Office in Haiti at the earliest possible opportunity, and to foster contacts at all levels between the citizens of Haiti and the people of the Caribbean Community.[25]

Haiti was admitted as the fifteenth Member State of the Caribbean Community on 2 July 2002 following the deposit of the Instrument of Accession by Haiti for membership[26] at the 23rd Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government in Georgetown, Guyana[27] after Haiti's parliament ratified the Treaty of Chaguaramas as well as the terms and conditions for Haiti's entry as a full member of the Caribbean Community including the Single Market and Economy in May 2002.[28]

Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten and the Netherlands

Aruba is an observer of CARICOM, as was the Netherlands Antilles before its dissolution in 2010. No official report has been published on the eligibility for observer status of the Caribbean countries Curaçao and Sint Maarten and the three special municipalities of the Netherlands formed by the split.

The Netherlands Antilles had applied for the status of associate membership in 2005,[29] and both Curaçao and Sint Maarten launched applications to become associate members in CARICOM after their secession.[30] In February 2012, the Prime Minister of Sint Maarten, Sarah Wescot-Williams said she was pleased that a working group had been set up in Caricom to examine St. Maarten's request for associate membership and was looking forward to its report.[31] Former Caribbean Association of Industry and Commerce (CAIC) Secretary Ludwig Ouenniche said the St. Maarten Chamber of Commerce, of which he also served as a board member, has been "aggressive in advising" the St. Maarten government to move towards a closer relationship with CARICOM over the years due to the Chamber's membership in the CAIC. The benefits for St. Maarten are vast, especially the ability to tap into funding and programmes not accessible now because of non-membership, he added. Caricom countries are benefiting from European Union funding and other sources of financing shut off to St. Maarten because of its constitutional position as a country within the Dutch Kingdom; associate membership would clear this barrier. Among the benefits would be access to cheaper generic medication to treat, for example, HIV/AIDS thanks to Caricom agreements and programmes. What makes this move even more important is the benefit the country would be able to reap for the large number of people living in St. Maarten who are originally from Caricom member countries; according to Ouenniche "some 65 per cent" of St. Maarten's population is of Caricom origin.[32]

In September 2015, a delegation from Sint Maarten met with the Caricom Secretary-General to continue discussing the terms and conditions of the associate membership status that St. Maarten is seeking. The delegation also received information on the work, structure and ongoing reforms of the Secretariat and the Community. As an observer, St. Maarten has attended meetings of the COHSOD (Council for Human and Social Development) and participates in the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) and offers the Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) curricula and examinations in its schools.[33] In October 2016, at the margins of an EU-Caribbean conference on sustainable energy in Bridgetown, Barbados, the Prime Minister of Sint Maarten, William Marlin, met with CARICOM's Secretary General Ambassador Mr. Irwin LaRocque to discuss the progress of Sint Maarten's application for associate membership and the potential for further, structured regional cooperation between CARICOM/CARIFORUM and the Caribbean Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) of the EU. Ambassador LaRocque informed Prime Minister Marlin that the associate membership applications of Sint Maarten, Curaçao and Aruba were being attended to be a technical working group established specially for devising the terms and conditions of associate membership, as such terms had not been spelled out in the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas. LaRocque also noted that CARICOM was working on an enlargement policy for new member states to be submitted to the Heads of Government for agreement by the end of the year. Sint Maarten had officially applied for associate membership of CARICOM in January 2014 when it sent an official letter of interest.[34]

Suriname (1973-1996)

In the 1973, around the time the Caribbean Free Trade Association was being transformed into CARICOM, Suriname was granted Liaison Status/Observer Status in the Association.[21][35][36] This followed on from a decision of the Conference of Commonwealth Caribbean Heads of Government in 1972 to study the possibility of extending the integration movement to include all the Caribbean islands and Suriname.[37] This marked the beginning of the re-engagement of Suriname and Anglophone Caribbean in terms of economic and political cooperation, following a period from 1926 to the 1960s when representatives from Suriname first attended the British Guiana and West Indian Labour Conferences (BGWILC) and then became members of the Caribbean Labour Congress.[38][39][40][41][42] The early Labour Conferences had called for the establishment of a federation in the British West Indies, and eventually also led to the establishment of the CLC in 1945.[38][42][39] The CLC itself was active until 1956, at which point it was dissolved following first a schism in the regional trade union movement that reflected the global split between the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) and the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) in 1949, and secondly the establishment of a rival body, the Caribbean Division of ORIT (the ICFTU Inter American Regional Organisation of Workers) or CADORIT in 1952.[38][42] CADORIT continued to consist of representatives from the British and Dutch West Indies (including Suriname) and was transformed in the Caribbean Congress of Labour (CCL) in 1960, again with the same membership that included Suriname.[38][42] By then however the early drive of the BGWILC/CLC to promote economic and political cooperation among its delegates' member territories had lost steam, partly because of the successful achievement of a federation among some of the British West Indian territories in 1958 and because that very federation began to falter in 1961–1962. The prospects for economic integration of Suriname with the Anglophone Caribbean only briefly experienced a resurgence in 1964-1965 as Eric Williams had engaged in (ultimately failed) diplomacy to establish a Caribbean Economic Community encompassing all of the Anglophone Caribbean, the Dutch West Indies (Netherlands Antilles and Suriname) and the French West Indies.[43]

On 14 April 1974, Suriname (along with Haiti) signified its desire to join CARICOM at the ceremony in St. Lucia marking the signing of the Treaty of Chaguaramas by the LDCs.[20] Talks of regional cooperation between Suriname and CARICOM were undertaken in the early 1970s, but integration was not further pursued, in part due to the perceived difficulties of integrating Suriname's very different legal system with that of the Commonwealth Caribbean countries.[44] Suriname continued to be an observer with regards to CARICOM after it came into existence, participating in a number of meetings of functional committees since the 1970s.[21] In the 1980s, Suriname expressed renewed interest in CARICOM[45] with initiatives to seek closer ties with the Community being welcomed in January 1982 by then Secretary-General Dr. Kurleigh King on a visit to the country[46][47] and the Surinamese application for closer relations with the Community being considered at the November 1982 Conference of the Heads of Government.[6] However, opposition by the member states to fuller Surinamese participation in CARICOM developed after the December 1990 "telephone coup" in Suriname, although Suriname retained observer status.[48] After democracy and civilian control was restored through the 1991 elections, Suriname began taking concrete steps to open its economy, emerge from isolation, and forge a new regional identity.[44] As a result, the ties between Suriname and the Community deepened and a Coordinating Unit for CARICOM Affairs was established and located in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Suriname. The CARICOM Coordinating Unit in Suriname had a core of three officers and was assisted in its task by CARICOM focal point officers representing the various other ministries with a supportive role being played by the Embassy of Guyana.[49]

At the Second Special Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government in October 1992, it was affirmed by the Conference that membership or a special form of relationship should be open to Suriname with regards to the Community.[50] In 1993 an Action Plan for Cooperation among the Caribbean Community, Suriname and the Group of Three was negotiated covering a wide range of areas including business, small enterprise development, tourism, transport, culture, science, agriculture, multilateral financing, and hemispheric trade.[51] In 1994 Suriname applied for full membership of the Community and Common Market, with the application being welcomed by the Heads of Government at the Fifteenth Meeting of the Conference. It was agreed to establish a review process including a small technical group to develop, with the Government of Suriname, under the co-ordination of the Bureau of the Conference, details with respect to both the application for membership of the Community, and the transitional arrangements with respect to membership of the Common Market. The Conference agreed that they would seek to make a determination of the application at the next Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference.[50] At that Inter-Sessional Meeting the Heads of Government agreed to approve the application by Suriname for membership in the Caribbean Community and Common Market with effect from the Sixteenth Meeting of the Conference, in July 1995, on terms and conditions agreed by both sides.[52]

On 4 July 1995, The Conference formally admitted Suriname as the fourteenth Member of the Caribbean Community, following the deposit of the Instruments of Accession to the Treaty of Chaguaramas and the Common Market Annex. The instrument of Accession to the Common Market made provision for Suriname to implement the arrangements relating to the Common Market effective 1 January 1996.[53] Suriname's accession to the Community and the Common Market led to significant changes in Suriname's external trade policy as prior to accession, a multiple tariff regime ranging from 0 to 100 percent under the Brussels Tariff Nomenclature (BTN) classification system was in force. In preparation for CARICOM membership, this system was replaced in 1994 with the Harmonized System (HS) used as the basis for determining duty-free entry of goods of CARICOM origin and for applying the common external tariff. Suriname's 1996 entry into the free trade area was immediate with no major transition phase contemplated in the accession agreement apart from some exceptions granted under the Treaty of Chaguaramas and a few others negotiated by Suriname upon entry.[44]

United States Virgin Islands

In 2007, the U.S. Virgin Islands government announced it would begin seeking ties with CARICOM.[54] At the time it was not clear what membership status the USVI would obtain should they join CARICOM with the most likely possibility being observer status, considering fellow U.S. Caribbean territory Puerto Rico's current observer status. In 2012, it was confirmed by the USVI Commissioner of Tourism, Beverly Nicholson-Doty, that the U.S. Virgin Islands government has been lobbying for observer status within CARICOM.[55]

At a meeting of the Caribbean Tourism Organization in Martinique on October 19, 2013, the Governor of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) John de Jongh said his administration has drafted legislation that will allow visitors from the CARICOM full members and associate members to enter that territory without a US visa. This comes as part of the USVI government's plans to encourage more CARICOM nationals to visit the USVI.[56]

If successful the proposal would recreate the visa-free regime which existed for CARICOM nationals travelling to the USVI prior to 1975. At that time, the United States imposed visa requirements on Commonwealth Caribbean nationals travelling to the USVI, resulting in the 1975 Caricom Heads of Government Conference passing a resolution expressing concerning for the viability of the LIAT airline as a result of the new visa requirements and calling on the United States to revise the new visa policy and to implement the required measures arising from decisions at a meeting of Labour Departments and Ministries of English-speaking Caribbean countries in St. Thomas to institute screening procedures in order regularize the immigration of CARICOM nationals to the USVI.[4]

de Jongh said the proposal has received bi-partisan support in the US House of Representatives[57] as well as support the Senate and the Department of Homeland Security,[56] but admits he doesn't know how soon the regime could be implemented, noting the pace of legislation in the U.S. Congress.[56][57]

The governor is, however, confident of a positive outcome having already had discussions on the subject with officials from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security “to come up with a regime which they will feel comfortable with.”[57]

de Jongh said the US Virgin Islands wants closer relations with the 15-member CARICOM grouping[58] and wants an opportunity to share in the movement of Caribbean nationals throughout the region[56] and is convinced that making travel easier for Caricom countries' nationals will be beneficial to the territories.[57]

“We recognise that with respect to sports tourism, sailing events and shopping, the region presents tremendous opportunity”, De Jongh told regional journalists.[57]

The initiative by de Jongh is actually not new having been first launched in 2012,[59] when de Jongh was quoted as saying that the “waivers would be specifically for individuals who are traveling for sporting events, medical services, and general tourism”.[60]

de Jongh is further quoted as saying: “We fully believe that such a change would broaden our reach into neighboring Caribbean markets. The territory’s sporting events are growing in popularity and prestige, especially for competitions in volleyball, track, tennis, swimming and sailing. An amendment to the immigration bill would allow for easier travel for athletes, as well as for individuals seeking top-notch medical care or just looking for a great place for a vacation, that is close to home.”[60]

The bill was relaunched (entitled The Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2013)[61] and introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives on May 14, 2013 and was referred to the House Judiciary's Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security.[62] It was not enacted during the life of that Congress.[62]

On April 29, 2015 the new Virgin Islands delegate, Stacey Plaskett, reintroduced the identical bill (now entitled The Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2015) to the U.S. House of Representatives.[63] On the same day it was referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary and then on June 1, 2015 it was referred to the House Judiciary's Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security[64] Like the 2013 bill, this one also died during the life of the Congress, and the legislation was reintroduced by Plaskett in 2017 (The Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2017) in the next Congress.[65][66]

Delegate Plaskett, stated that the Bill (along with two others introduced by her) were geared towards improving the economy of the US Virgin Islands, with the special visa waiver program in particular aimed at boosting tourism by allowing the US Virgin Islands host more participants in seasonal regional sporting events and patients intending to access the US Virgin Islands' medical facilities without the need for visas.[67][68]

Caricom nationals would still require a visa to travel to the U.S. mainland and other U.S. territories.[57]

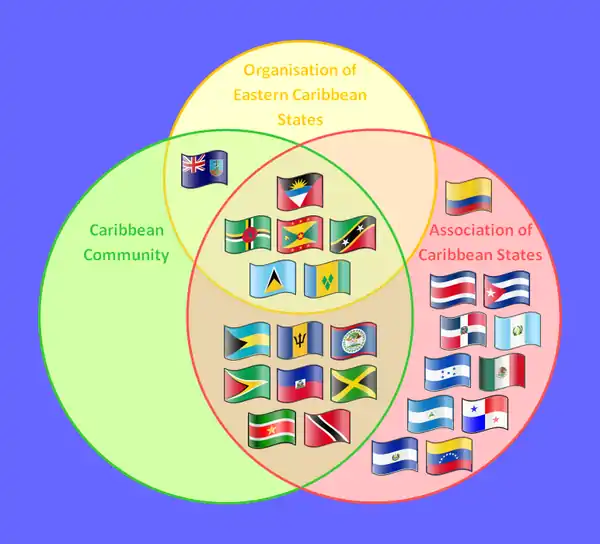

Relationship to other supranational Caribbean organisations

Although the group has close ties with Cuba, that nation was excluded due to lack of full democratic internal political arrangement.

References

- "Treaty of Chaguarmas" (PDF). 4 July 1973.

- 8th Meeting of Heads of Government of Commonwealth Caribbean Countries, 9-12 April 1973, Georgetown, Guyana Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Area Handbook for Jamaica. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1976.

late 1974 bahamas indicated caricom.

- 2nd Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, 8-10 December 1975, Basseterre, St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla Archived 6 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- LeVeness, Frank Paul (1974). Caribbean integration: the formation of Carifta and the Caribbean Community. Department of Government and Politics, St. John's University. p. 56.

- 3rd Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, 16-18 November 1982, Ocho Rios, Jamaica Archived 6 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- 4th Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, 4-8 July 1983, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago Archived 6 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- The EU and Cariforum

- "Dominican Republic in CARICOM?". Caribbeannetnews.com. 2011-03-18. Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- Expand CARICOM to include French, Dutch and Spanish

- "Letter: Privy Council and EPA" Archived 2014-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, October 8, 2009, Jamaica Gleaner

- Dominican Republic bids again to join Caricom

- Trinidad PM Urges CARICOM to Accept Dominican Republic as Member

- Stuart: Dominican Republic Committed to Joining CARICOM

- "CARICOM STATEMENT ON DEVELOPMENTS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RULING OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ON NATIONALITY". CARICOM. 2013-11-26. Archived from the original on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- Richards, Peter (2013-11-27). "CARICOM defers Dominican Republic application amid row over court ruling". Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- "Communique issued at the Conclusion of the 34th Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government in July 2013". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- "French territories seeking associate membership within CARICOM". Archived from the original on 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- Haiti and CARICOM: The Challenges of Regional Integration

- Hippolyte-Manigat, Mirlande (1980). Haiti and the Caribbean Community: Profile of an Applicant and the Problematique of Widening the Integration Movement. Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of the West Indies. p. 256.

- Girvan, Norman (1989). Development in Suspense: Selected Papers and Proceedings of the First Conference of Caribbean Economists. ACE. p. 366. ISBN 976-80-0132-1.

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of the Eighteenth Heads of Government Conference, July 1997 Archived 2015-08-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of The Twentieth Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), 4-7 July 1999 Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of The Twelfth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government held at the Sherbourne Conference Centre, Barbados from 14 to 16 February 2001 Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- 2001 Statement on the Caribbean Community's relations with Haiti Archived 2015-06-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of The Twenty-Third Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government held in Georgetown, Guyana, on 3-5 July 2002 Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- 29 November 2002 Press Release: CARICOM keeps up the pace Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- 03 June 2002 Press Release: CARICOM prepares for Civil Society Encounter, Summit Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Netherlands Antilles policy towards the Caribbean is one of committed neighbour". Caribbeannetnews.com. 2011-03-18. Archived from the original on 2009-07-17. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- "Committee appointed to handle Caricom application". Today. 2012-02-15. Archived from the original on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Sarah pleased with progress on Caricom associate membership

- Ouenniche: Associate membership of Caricom ‘win-win’ situation for country

- Prime Minister Marlin discusses Associate Membership to CARICOM during Barbados working visit

- CARIFTA and Caribbean Trade: An Overview

- "CARICOM: Externally Vulnerable Regional Integration" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- 7th Meeting of Heads of Government of Commonwealth Caribbean Countries, 9-14 October, 1972, Chaguaramas, Trinidad and Tobago Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Alexander, Robert (2009). International Labor Organizations and Organized Labor in Latin America and the Caribbean: A History. ABC-CLIO. p. 312. ISBN 9780275977399.

- 70th Anniversary of the Caribbean Labour Congress/Barbados Conference

- The Visions, Struggles and Victories of Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow

- Lewis, William Arthur (1977). Labour in the West Indies: The Birth of a Worker's Movement. New Beacon Books. p. 104.

- Alexander, Robert (2004). A History of Organized Labor in the English-speaking West Indies. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 485. ISBN 9780275977436.

- Payne, Anthony (2008). The Political History of CARICOM. Ian Randle Publishers. p. 306. ISBN 9789766372927.

- Breaking from Isolation: Suriname's Participation in Regional Integration Initiatives

- Thomas-Hope, Elizabeth (1984). Perspectives on Caribbean Regional Identity, Volume 11 of Centre for Latin American Studies Liverpool: Monograph series. Centre for Latin American Studies, University of Liverpool. p. 134. ISBN 9780841910003.

- Institute of Caribbean Studies (1982). Caribbean Monthly Bulletin, Volume 16. Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico.

- Heine, Jorge (1988). The Caribbean and world politics: cross currents and cleavages. Holmes & Meier. p. 385. ISBN 084-19-1000-6.

- Day, Alan (1992). The Annual Register, 1991: A Record of World Events. Gale / Cengage Learning. p. 618. ISBN 058-20-9585-9.

- Rainford, Roderick (1991). Annual report of the Secretary-General of the Caribbean Community. CARICOM Secretariat.

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of The Fifteenth Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government held at the Sherbourne Conference Centre, Bridgetown, Barbados, 4 – 7 July 1994 Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Action Plan for Co-operation Among the Caribbean Community, Suriname and the Group of Three Archived 2015-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of The Sixth Inter-Sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community was held in Belize City, Belize on 16–17 February 1995 Archived 18 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Communique Issued at the Conclusion of The Sixteenth Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community was held in Georgetown, Guyana on 4 – 7 July, 1995 Archived 2015-06-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "USVI, BVI leaders discuss areas of mutual interest"

- US Virgin Islands seeks closer cooperation with its neighbours

- US Virgin Islands To Waive Visa Restrictions For CARICOM Citizens

- USVI visa waiver likely for Caricom nationals

- USVI Moving Toward Visa-Free Travel For CARICOM Nationals

- H.R. 5875 (112th): Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2012

- REGIONAL: USVI starts legislative measure aimed at removing visa requirement for CARICOM nationals

- H.R. 1966: Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2013

- "H.R.1966: Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2013"

- H.R.2116: Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2015

- All Actions H.R.2116 (Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2015) — 114th Congress (2015-2016)

- H.R.187: Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act of 2017

- House Bill: Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Act, 2017

- Plasket introduces legislation granting visa waiver to Caricom countries

- Plaskett Introduces New Legislation Aimed At Improving Economic Conditions In The Territory