Microcomputer

A microcomputer is a small, relatively inexpensive computer with a microprocessor as its central processing unit (CPU).[1] It includes a microprocessor, memory and minimal input/output (I/O) circuitry mounted on a single printed circuit board (PCB).[2] Microcomputers became popular in the 1970s and 1980s with the advent of increasingly powerful microprocessors. The predecessors to these computers, mainframes and minicomputers, were comparatively much larger and more expensive (though indeed present-day mainframes such as the IBM System z machines use one or more custom microprocessors as their CPUs). Many microcomputers (when equipped with a keyboard and screen for input and output) are also personal computers (in the generic sense).[3]

The abbreviation micro was common during the 1970s and 1980s,[5] but has now fallen out of common usage.

Origins

The term microcomputer came into popular use after the introduction of the minicomputer, although Isaac Asimov used the term in his short story "The Dying Night" as early as 1956 (published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in July that year).[6] Most notably, the microcomputer replaced the many separate components that made up the minicomputer's CPU with one integrated microprocessor chip.

The French developers of the Micral N (1973) filed their patents with the term "Micro-ordinateur", a literal equivalent of "Microcomputer", to designate a solid state machine designed with a microprocessor. In the US the earliest models such as the Altair 8800 were often sold as kits to be assembled by the user, and came with as little as 256 bytes of RAM, and no input/output devices other than indicator lights and switches, useful as a proof of concept to demonstrate what such a simple device could do.[7] As microprocessors and semiconductor memory became less expensive, microcomputers grew cheaper and easier to use.

- Increasingly inexpensive logic chips such as the 7400 series allowed cheap dedicated circuitry for improved user interfaces such as keyboard input, instead of simply a row of switches to toggle bits one at a time.

- Use of audio cassettes for inexpensive data storage replaced manual re-entry of a program every time the device was powered on.

- Large cheap arrays of silicon logic gates in the form of read-only memory and EPROMs allowed utility programs and self-booting kernels to be stored within microcomputers. These stored programs could automatically load further more complex software from external storage devices without user intervention, to form an inexpensive turnkey system that does not require a computer expert to understand or to use the device.

- Random access memory became cheap enough to afford dedicating approximately 1-2 kilobytes of memory to a video display controller frame buffer, for a 40x25 or 80x25 text display or blocky color graphics on a common household television. This replaced the slow, complex, and expensive teletypewriter that was previously common as an interface to minicomputers and mainframes.

All these improvements in cost and usability resulted in an explosion in their popularity during the late 1970s and early 1980s. A large number of computer makers packaged microcomputers for use in small business applications. By 1979, many companies such as Cromemco, Processor Technology, IMSAI, North Star Computers, Southwest Technical Products Corporation, Ohio Scientific, Altos Computer Systems, Morrow Designs and others produced systems designed for resourceful end users or consulting firms to deliver business systems such as accounting, database management and word processing to small businesses. This allowed businesses unable to afford leasing of a minicomputer or time-sharing service the opportunity to automate business functions, without (usually) hiring a full-time staff to operate the computers. A representative system of this era would have used an S100 bus, an 8-bit processor such as an Intel 8080 or Zilog Z80, and either CP/M or MP/M operating system. The increasing availability and power of desktop computers for personal use attracted the attention of more software developers. As the industry matured, the market for personal computers standardized around IBM PC compatibles running DOS, and later Windows. Modern desktop computers, video game consoles, laptops, tablet PCs, and many types of handheld devices, including mobile phones, pocket calculators, and industrial embedded systems, may all be considered examples of microcomputers according to the definition given above.

Colloquial use of the term

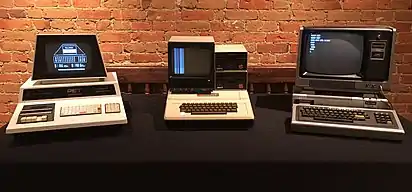

By the early 2000s, everyday use of the expression "microcomputer" (and in particular "micro") declined significantly from its peak in the mid-1980s.[8] The term is most commonly associated with the most popular all-in-one 8-bit home computers (such as the Apple II, ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64, BBC Micro, and TRS-80) and small-business CP/M-based microcomputers. Because an increasingly diverse range of devices based on modern microprocessors lack the most common characteristic of "microcomputers," having an 8-bit data bus, they are not referred to as such in everyday speech.

In colloquial usage, "microcomputer" has been largely supplanted by the term "personal computer" or "PC", which specifies a computer that has been designed to be used by one individual at a time, a term first coined in 1959.[9] IBM first promoted the term "personal computer" to differentiate the IBM PC from CP/M-based microcomputers likewise targeted at the small-business market, and also IBM's own mainframes and minicomputers. However, following its release, the IBM PC itself was widely imitated, as well as the term. The component parts were commonly available to producers and the BIOS was reverse engineered through cleanroom design techniques. IBM PC compatible "clones" became commonplace, and the terms "personal computer", and especially "PC", stuck with the general public, often specifically for a computer compatible with DOS (or nowadays Windows).

Description

Monitors, keyboards and other devices for input and output may be integrated or separate. Computer memory in the form of RAM, and at least one other less volatile, memory storage device are usually combined with the CPU on a system bus in one unit. Other devices that make up a complete microcomputer system include batteries, a power supply unit, a keyboard and various input/output devices used to convey information to and from a human operator (printers, monitors, human interface devices). Microcomputers are designed to serve only one user at a time, although they can often be modified with software or hardware to concurrently serve more than one user. Microcomputers fit well on or under desks or tables, so that they are within easy access of users. Bigger computers like minicomputers, mainframes, and supercomputers take up large cabinets or even dedicated rooms.

A microcomputer comes equipped with at least one type of data storage, usually RAM. Although some microcomputers (particularly early 8-bit home micros) perform tasks using RAM alone, some form of secondary storage is normally desirable. In the early days of home micros, this was often a data cassette deck (in many cases as an external unit). Later, secondary storage (particularly in the form of floppy disk and hard disk drives) were built into the microcomputer case.

History

TTL precursors

Although they did not contain any microprocessors, but were built around transistor-transistor logic (TTL), Hewlett-Packard calculators as far back as 1968 had various levels of programmability comparable to microcomputers. The HP 9100B (1968) had rudimentary conditional (if) statements, statement line numbers, jump statements (go to), registers that could be used as variables, and primitive subroutines. The programming language resembled assembly language in many ways. Later models incrementally added more features, including the BASIC programming language (HP 9830A in 1971). Some models had tape storage and small printers. However, displays were limited to one line at a time.[10] The HP 9100A was referred to as a personal computer in an advertisement in a 1968 Science magazine,[11] but that advertisement was quickly dropped.[12] HP was reluctant to sell them as "computers" because the perception at that time was that a computer had to be big in size to be powerful, and thus decided to market them as calculators. Additionally, at that time, people were more likely to buy calculators than computers, and, purchasing agents also preferred the term "calculator" because purchasing a "computer" required additional layers of purchasing authority approvals.[13]

The Datapoint 2200, made by CTC in 1970, was also comparable to microcomputers. While it contains no microprocessor, the instruction set of its custom TTL processor was the basis of the instruction set for the Intel 8008, and for practical purposes the system behaves approximately as if it contains an 8008. This is because Intel was the contractor in charge of developing the Datapoint's CPU, but ultimately CTC rejected the 8008 design because it needed 20 support chips.[14]

Another early system, the Kenbak-1, was released in 1971. Like the Datapoint 2200, it used small-scale integrated transistor–transistor logic instead of a microprocessor. It was marketed as an educational and hobbyist tool, but it was not a commercial success; production ceased shortly after introduction.[15]

Early microcomputers

In late 1972, a French team headed by François Gernelle within a small company, Réalisations & Etudes Electroniques (R2E), developed and patented a computer based on a microprocessor – the Intel 8008 8-bit microprocessor. This Micral-N was marketed in early 1973 as a "Micro-ordinateur" or microcomputer, mainly for scientific and process-control applications. About a hundred Micral-N were installed in the next two years, followed by a new version based on the Intel 8080. Meanwhile, another French team developed the Alvan, a small computer for office automation which found clients in banks and other sectors. The first version was based on LSI chips with an Intel 8008 as peripheral controller (keyboard, monitor and printer), before adopting the Zilog Z80 as main processor.

In late 1972, a Sacramento State University team led by Bill Pentz built the Sac State 8008 computer,[16] able to handle thousands of patients' medical records. The Sac State 8008 was designed with the Intel 8008. It had a full set of hardware and software components: a disk operating system included in a series of programmable read-only memory chips (PROMs); 8 Kilobytes of RAM; IBM's Basic Assembly Language (BAL); a hard drive; a color display; a printer output; a 150 bit/s serial interface for connecting to a mainframe; and even the world's first microcomputer front panel.[17]

In early 1973, Sord Computer Corporation (now Toshiba Personal Computer System Corporation) completed the SMP80/08, which used the Intel 8008 microprocessor. The SMP80/08, however, did not have a commercial release. After the first general-purpose microprocessor, the Intel 8080, was announced in April 1974, Sord announced the SMP80/x, the first microcomputer to use the 8080, in May 1974.[18]

Virtually all early microcomputers were essentially boxes with lights and switches; one had to read and understand binary numbers and machine language to program and use them (the Datapoint 2200 was a striking exception, bearing a modern design based on a monitor, keyboard, and tape and disk drives). Of the early "box of switches"-type microcomputers, the MITS Altair 8800 (1975) was arguably the most famous. Most of these simple, early microcomputers were sold as electronic kits—bags full of loose components which the buyer had to solder together before the system could be used.

The period from about 1971 to 1976 is sometimes called the first generation of microcomputers. Many companies such as DEC,[19] National Semiconductor,[20] Texas Instruments[21] offered their microcomputers for use in terminal control, peripheral device interface control and industrial machine control. There were also machines for engineering development and hobbyist personal use.[22] In 1975, the Processor Technology SOL-20 was designed, which consisted of one board which included all the parts of the computer system. The SOL-20 had built-in EPROM software which eliminated the need for rows of switches and lights. The MITS Altair just mentioned played an instrumental role in sparking significant hobbyist interest, which itself eventually led to the founding and success of many well-known personal computer hardware and software companies, such as Microsoft and Apple Computer. Although the Altair itself was only a mild commercial success, it helped spark a huge industry.

Home computers

By 1977, the introduction of the second generation, known as home computers, made microcomputers considerably easier to use than their predecessors because their predecessors' operation often demanded thorough familiarity with practical electronics. The ability to connect to a monitor (screen) or TV set allowed visual manipulation of text and numbers. The BASIC language, which was easier to learn and use than raw machine language, became a standard feature. These features were already common in minicomputers, with which many hobbyists and early produces were familiar.

In 1979, the launch of the VisiCalc spreadsheet (initially for the Apple II) first turned the microcomputer from a hobby for computer enthusiasts into a business tool. After the 1981 release by IBM of its IBM PC, the term personal computer became generally used for microcomputers compatible with the IBM PC architecture (PC compatible).

See also

- History of computing hardware (1960s-present)

- Lists of microcomputers

- Mainframe computer

- Minicomputer

- Personal computer

- Supercomputer

Notes and references

- "Microcomputer". dictionary.com.

- A.O., Williman; Jelinek, H.J. (June 1976). "Special Tutorial: Introduction to LSI Microprocessor Developments". Computer. IEEE. 9 (Computer): 37. doi:10.1109/C-M.1976.218612. S2CID 11184882.

- An early use of the term personal computer in 1962 predates microprocessor-based designs. (See "Personal Computer: Computers at Companies" reference below). A microcomputer used as an embedded control system may have no human-readable input and output devices. "Personal computer" may be used generically or may denote an IBM PC compatible machine.

- Kahney, Leander (2003-09-09). "Grandiose Price for a Modest PC". Wired. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- Proof of "micro" as a once-common term:

(i) Direct reference: Graham Kibble-White, "Stand by for a Data-Blast", Off the Telly. Article written December 2005, retrieved 2006-12-15.

(ii) Usage in the titles of Christopher Evans' books "The Mighty Micro" (ISBN 0-340-25975-2) and "The Making of the Micro" (ISBN 0-575-02913-7). Other books include Usborne's "Understanding the Micro" (ISBN 0-86020-637-8), a children's guide to microcomputers. - Asimov, Isaac (July 1956). "The Dying Night". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

- Ceruzzi, Paul (2012). Computing: a concise history. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780262517676.

- "microcomputer". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 15 February 2014.

- "personal computer". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 15 February 2014

- "The Museum of HP Calculators".

- "Powerful Computing Genie" (PDF). Hewlett Packard. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "Restoring the Balance Between Analysis and Computation" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "History of the 9100A desktop calculator, 1968". HP virtual museum. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- "MicroprocessorHistory". Computermuseum.li. 1971-11-15. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "Kenbak-1". The Vintage Computer.

- "Digibarn Stories: Bill Pentz and (Earliest) History of the Microcomputer (August 2008)". Digibarn.com. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Terdiman, Daniel (2010-01-08). "Inside the world's long-lost first microcomputer | Geek Gestalt — CNET News". News.cnet.com. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "SMP80/X series-Computer Museum".

- "16-bit timeline". 19 November 1997.

- "Paper Tape Readers Work With IMP Micros". Computerworld. 23 Oct 1974. p. 28.

- "Upward Compatible Software and Downward Compatible Price". Computerworld. 10 Dec 1975. p. 49.

- Hawkins, William J. (December 1983). "Computer Adventures". Popular Science.